|

Supplement

Centenary of the End of World War I Contributions and Slaughter of Colonial Peoples in World War I

Colonial Peoples' Resistance in World War One The imperialist warmongers today continue to propagate

the

disinformation that the colonial peoples from Africa, Asia, the

Middle East and the Caribbean were enthusiastic to serve in the armies

of their imperialist overlords in World War One.

This is entirely self-serving because it covers up that the

peoples from around the world who were living under the yoke of

British, French, Belgian, German, Japanese and other

colonizers, were being terrorized, enslaved and exploited, their

resources stolen and their striving for independence and

self-determination criminalized. They were not enthusiastic, to

say the least, for their youth to be used as cannon fodder in an

imperialist war between rival European powers. With the outbreak of World War I, some 4,000,000 people

in the colonial empires of the belligerent countries in Africa, Asia

and elsewhere, were automatically at war too. From Germany's African

colonies 200,000 porters were conscripted, from France's African

colonies 450,000 soldiers. Not only were troops from the colonies in

Africa and Asia conscripted to fight in Europe, but military

engagements took place in Africa and Asia, including the so-called

Middle East, making it a truly global conflict. In East Africa alone it

is estimated that 1,000,000 people were killed in the war. Speaking in 1925, the great leader of the Vietnamese people, Ho Chi Minh, noted that the 100,000 Indochinese people who participated in World War One -- half in the French army and the other half as non-combatant labourers -- "were taken in chains ... most of them to never again see the sun of their country."[1] There has been little enthusiasm among the warmongers,

including in Canada, to tell the truth about the colonial

peoples' resistance in and to the First World War, in order to

justify war and occupation of these former colonial countries

today. The reality is that there were many small and large acts

of resistance against the attempts of the British, French, German

and other colonizers to force the people they oppressed to

participate in their bloody imperialist war. Still, some four

million combat and non-combat participants from Asia, Africa, the

Middle East and the Caribbean were involved in the First World

War, drawn from the poorest of the poor, the unemployed and

illiterate in the colonies. For example, more than 90 per cent

of the Indian troops who were involved in the war were poor

illiterate peasants.[2] In the period following the November 11, 1918 armistice,

the victorious powers redivided the world between themselves, at the

expense of the Ottoman Empire and Germany and especially the colonial

peoples living there. In Africa, Germany's colonies were handed over to

Britain and France, or in the case of German Kamerun and Togoland

divided between them. Far from being the war to end all wars, World War

I perpetuated the colonial system, denied nations the right to

self-determination and sowed the seeds of future conflicts and wars in

Europe and globally.

Resistance and Rebellion in AfricaOf the many acts of rebellion by the African peoples to the First World War, two stand out. The Chilembwe Uprising

John Chilembwe was a Baptist church minister in the former Nyasaland, now Malawi. He was well aware of and spoke out against the abuses of the British colonialists against his people -- the theft of their lands, the brutal exploitation of African labour and abusive labour practices, including flogging and overwork of plantation workers. Following the outbreak of the First World War, in October 1914, Chilembwe wrote a letter to the editor of the Nyasaland Times on behalf of chiefs, headmen and elders, to express the people's objections to being drawn into the British war effort. It said in part, "I hear that, war has broken out between you and other nations, only whitemen, I request, therefore, not to recruit more of my countrymen, my brothers who do not know the cause of your fight, who indeed, have nothing to do with it ... It is better to recruit white planters, traders, missionaries and other white settlers in the country, who are, indeed, of much value and who also know the cause of this war and have something to do with it." The letter was rejected by the censor.

The forced

recruitment of local youth for the war by the British ultimately led to

Chilembwe and members of his congregation, which included local

teachers, taking up arms against the British, in what would become

known as the Chilembwe Uprising.[3] On January 23, 1915, Chilembwe

and his followers attacked a local British plantation and also an

arsenal nearby where they seized weapons. The uprising lasted three

days before it was brutally crushed by the British military, resulting

in the summary execution of some 40 of the insurgents and the

imprisonment of more than 300. Chilembwe himself was shot dead as he

attempted to seek refuge in nearby Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique).

An inquiry into the uprising carried out by the British colonial

authorities confirmed that the local British plantations had treated

their workers as slave labour and punished their workers with impunity.

The memory of the Chilembwe Uprising inspired the people of the region

in their anti-colonial fight against British imperialism in the coming

decades.

Volta-Bani Uprising When the First World War broke out, the French needed recruits for the front. They were keen first of all to recruit Africans including from Algeria and Morocco. When the French introduced conscription in West Africa, the people rose up against them. French colonial administrators spent much of their time during the war trying to neutralize the people's resistance to conscription. Africans in the French colonies of West Africa feigned illness, abandoned villages and took up armed revolt in northern Dahomey (now Benin), north of Bamako (now in Mali) and in the southern desert of French Sudan (now in Niger).[4] One of the main acts of resistance to French colonialism during the war was the Volta-Bani Uprising against conscription which began in 1915 when a few villages in the area united against the French. At its height in 1916, the rebels numbered from 15,000 to 20,000 men who fought on several fronts and struck terror in the hearts of the colonizers. After about a year and having been defeated on several occasions, the French took action and concentrated 6,000 regular army and mercenary troops to put down the rebellion. The French carried out a "scorched earth" campaign against the insurgents, sacking and bombarding their villages and massacring the people, including women and children, as a warning to others. The leaders were executed and many others jailed. After the war, to continue their rule by dividing the people, the French colonizers created the colony of Haute Volta (now Burkina Faso), by splitting off seven insurgent districts from the large colony of Haut-Sénégal and Niger.[5] The Volta-Bani Uprising was one of the key uprisings against the French that served to inspire other such anti-colonial struggles in the region and in other parts of Africa.

Resistance in VietnamNumerous revolts took place in Vietnam, which was part of French Indochina. When the war began, the French colonialists had been ruling French Indochina with an iron fist for almost 70 years, exploiting the labour and resources of the Vietnamese, Cambodian and other peoples of the region which sparked ongoing armed resistance. As a measure of the exploitation of the Vietnamese people during the war -- the French levied a "contribution" of 281 million gold francs, which was 60 per cent of the total imposed on all French colonies, and also forced the Vietnamese to provide 340,000 tons of raw materials which amounted to 34 per cent of all raw materials supplied by the colonies. When conscription was imposed by the French in Vietnam, resistance stepped up. Entire villages refused to cooperate and often the villagers drove away the recruiting officers. To deal with this resistance the French suppressed the patriotic organizations and imprisoned or executed their leaders. One of the most significant uprisings during this period was in the northern Vietnamese province of Thai Nguyen in 1917 where some 300 Vietnamese soldiers and prison guards revolted and released 200 political prisoners, who together with several hundred local people, held the town of Thai Nguyen for several days till the French arrived with reinforcements and suppressed the rebellion. The French were never again able to completely suppress the people's anti-colonial movement in that area.[6]

Resistance of the Caribbean Soldiers to Racist Attacks

While there were many newspapers in the West Indies

that

spoke out against the First World War as a war of the "Whites"

that did not concern West Indians, by 1915, the British War

Office, anticipating the need for more soldiers for the war

effort, and pressured by the ruling elites in the Caribbean

islands, created the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR)

comprised of workers drawn from Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad,

Guyana and other colonies in the region with the false promise of land

and other rewards following the war. A total of almost 16,000 men

served with this battalion. Conscientious objector Isaac Hall, who lived in England

in 1916, aptly expressed his countrymen's opposition to the war, when

he declared, "I am a Negro of the African race, born in Jamaica. My

country is divided up among the European Powers (now fighting against

each other) who in turn have oppressed and tyrannized over my

fellow-men. The allies of Great Britain, i.e. Portugal and Belgium,

have been among the worst oppressors, and now that Belgium is invaded I

am about to be compelled to defend her. In view of these circumstances,

and also the fact that I have a moral objection to all wars, I would

sacrifice my rights rather than fight." Hall was tortured and

incarcerated in Pentonville Prison in north London for two years but

refused to renounce his principles. The racist colonial outlook of the British imperialists

towards the peoples of the Caribbean was such that members of the BWIR

who served in Europe, the Middle East and

Africa, were most often put in service to do construction, labour

and other menial jobs. A small number saw combat duty at the

front. As well, the BWIR soldiers received less pay than their

British counterparts, were housed in the worst quarters, and

suffered various other humiliations.

On March 6, 1916, the Verdala, a ship

carrying

25 officers and 1,115 soldiers of the third Jamaica contingent of

the BWIR, departed for England. Due to enemy submarine activity

on route, the ship was ordered to make a detour to Halifax,

Canada. On route to Halifax, the ship encountered a blizzard and

because the soldiers were not properly equipped with warm

clothing, some 600 men suffered frostbite and exposure and five

died, a bitter foretelling of things to come. The Halifax

Incident seriously damaged the recruitment campaign, which had to

be temporarily suspended. The recruiters subsequently were forced to

adopt a more vigorous strategy of house-to-house visits and even

had to resort to recruiting from Panama when the U.S. entered the war

in 1917 to replenish the BWIR with new recruits.

Uprising at Taranto One of the most militant acts of resistance by the BWIR

occurred on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, at Taranto, a port in

southern Italy and a large logistics point for the British army, where

BWIR ballalions were concentrated for demobilization. Eight BWIR

battalions from France and Italy were joined by three BWIR battalions

from Egypt and Mesopotamia which caused a logistical crisis. The West Indians were ordered to assist with the loading and unloading of ships and other labour including cleaning the latrines for the white soldiers, which they themselves were barred from using. This led to simmering anger reaching a boiling point. On December 6, 1918, the men of the 9th Battalion of the BWIR revolted and attacked their officers. On the same day, 180 BWIR sergeants forwarded a petition to the British Secretary of State complaining of the pay discrimination, the failure to increase their separation allowance and protesting that they were discriminated against regarding promotions. On December 9, the 10th Battalion downed their tools. A senior officer who had ordered some BWIR men to clean the latrines of the Italian Labour Corps was assaulted. In response to a call for help from the commanders at Taranto, a machine-gun company and a battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment was brought in to restore order. The 9th BWIR was disbanded and its members sent to other battalions and the entire BWIR was disarmed. Sixty soldiers from the BWIR were charged with mutiny and those convicted were jailed for up to 20 years. One soldier was executed by firing squad. Of significance is that on December 17, 1918, a group of 60 Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) from the BWIR held a meeting to discuss their rights, self-determination for the nations of the West Indies and better cooperation. At another meeting one NCO affirmed that the "black man must have freedom to govern himself in the West Indies and that if necessary, force and bloodshed should be used to attain these aims."[7] They formed an organization called the Caribbean League to further these goals with its headquarters to be in Kingston, Jamaica and sub-offices in the other West Indian colonies. The First World War and the experience of the colonial peoples within it, and the inspiration drawn as a result of the Russian Revolution, made a qualitative change in consciousness among the colonial peoples. The war removed any doubt that the colonial powers were out to seize more wealth and booty for themselves and that the colonial peoples had to rely on their own initiative and just cause, to step up their organized resistance to colonial domination, and advance their struggle for self-determination, independence and peace. Notes1. Nguyen Ai Quoc. Le procès de la colonisation française. Hanoi, 1962, pp. 9-22; Joseph Buttinger, Vietnam. A Dragon Embattled, (Vol. 1. London: Pall Mall, 1967, pp. 116n, 490. 2. "Sepoy

Letters

(India), International

Encyclopedia of the First

World War. 3. "Resistance

and

Rebellions

(Africa)," International

Encyclopedia of the First

World War. 4. Jacques Enaudeau. "African resistance and rebellion: The other side of World War One," Al Jazeera, September 22, 2014 5. Mahir Saul and Patrick Royer. West African Challenge to Empire: Culture and History in the Volta-Bani Anti-Colonial War. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001, p. 1. 6. "Thái

Nguyên

Uprising," Wikipedia. 7. "History of

World War One," BBC. Massive Conscription of Indians by the British

Once World War I broke out, Britain called on all its Dominions and colonies for men and materiel. Of these, none bore a greater burden and sacrifice than India. By the end of the war, nearly one-and-a-half million soldiers and non-combatants from India had been brought to the Western Front in Europe and to the other theatres of war. Of these, around 70,000 were killed, and tens of thousands more left shell-shocked, blind, crippled or suffering other severe wounds and mental trauma. India was also bled dry in terms of foodstuffs and other resources for the war effort, with disastrous consequences. At the outbreak of war, the British Indian Army consisted of 76,953 British, 193,901 Indians and 45,600 non-combatants. It was claimed to be a "volunteer" army. Unlike Britain, there was no conscription in India during the war, though considering the disastrous effect that colonial plunder and exploitation had had on the Indian economy, regular pay and subsistence was an offer many could hardly refuse. It was a disciplined and experienced army. The British only recruited from what they termed "the martial races" from northern India: Pathans, Baluchis, Punjabi Muslims and Sikhs, Nepalese and others. No lower castes were recruited as soldiers, while thousands were employed for cleaning and other menial tasks. No Indians could become commissioned officers, only junior officers of the regiment, while even the most senior Indian officer was subordinate to the most junior British officer. Loyalty was primarily to the regiment, which functioned very much as a "family," the expression being "loyalty to the salt," to the provider. Regiments were organized on common regional, religious and linguistic lines, with many soldiers coming from the same villages. The British were ever-mindful of the lessons of 1857, when disaffection in the Indian Army was one factor which led to the First War of Independence.

Western Front

The first Indian troop ships arrived at Marseilles on September 26, 1914. They were warmly received by the local population. By early October two divisions of the Indian Army were encamped in France. Within just a few weeks they were moved north to the Western Front. Though winter was setting in, they did not have adequate clothing. They remained in their thin cotton khaki drill and sweaters which provided no protection from the wind, sleet and rain of the dark October and November months. In fact it was New Year before they were issued with greatcoats, by which time many had died from cold and frostbite. Initially it had been considered that the Indian troops would be used as reserve or garrison troops, but in fact they were sent straight into the front lines. Initial enthusiasm soon gave way to despair. The conditions in the trenches were appalling. As well as the bombing and incessant shelling, rains brought flooding. Disease was rife. Trenches collapsed. Frostbite was common. Letters home captured the situation. A Pathan soldier wrote: "No one who has ever seen the war will forget it to their last day. Just like a turnip cut into pieces, so a man is blown to bits by the explosion of a shell.... All those who came with me have all ceased to exist.... There is no knowing who will win. In taking a hundred yards of trench, it is like the destruction of the world." If soldiers were injured, they would be sent to the hospitals and convalescent depots in France. Once recovered, they would be returned to the front line. A wounded soldier wrote home: "I have no hope of surviving, as the war is very severe. The wounds get better in a fortnight and then one is sent back to the trenches.... The whole world is being sacrificed and there is no cession. It is not a war but a Mahabharat, the world is being destroyed." Despair was compounded by the fact that, while British soldiers were given regular home leave, no leave was ever given to the Indian troops. This was constantly asked for but refused. This despair was noted with concern by the British authorities. Ever wary of disaffection, they had taken great care, for instance, to provide separate cooking facilities and water supplies according to the various religious obligations, as well as other measures. Strict censorship of letters home was imposed. Many letters were stopped altogether. In addition great vigilance was shown by the authorities in preventing what they termed "seditious literature" reaching the troops. So concerned were they, for example, about literature from the Ghadar Party that all mail from San Francisco, Rotterdam and Geneva was closely monitored. Yet even in such trying circumstances, the Indian troops fought with great bravery. This was shown clearly in the battle to seize a German-held salient at Neuve Chapelle in February 1915. The battle raged over four days of relentless fighting. General Douglas Haig had believed a prolonged attack would produce results in the end, even if it meant taking heavy casualties. Both Indian divisions played a prominent part in the battle. One Indian soldier killed in action was awarded the Victoria Cross. In all 4,233 of the Indian Corps were killed, mainly from the heavy German artillery bombardment. Neuve Chapelle was taken. But in the four days of intense fighting and thousands of casualties, only 1,500 metres was gained. Subsequently Haig's report and numerous books written about the battle, including the British state's History of the Great War,[1] made scant if any mention of the contribution of the Indian troops. The Battle of Loos in September 1915 was to be one of

the

last major operations undertaken by the whole Indian Corps on the

Western Front. The battle raged for two weeks, yet no gains were

made. Casualties were high, with most battalions reduced to fewer

than a hundred. At the end of the year, having endured a second

winter in the trenches, the bulk of the Indian Corps were moved

to other theatres of war -- the Middle East, Gallipoli and Africa.

In early 1917, further Indian troops were recruited for these

theatres, where casualties had been high and reinforcements were

urgently needed. The Secretary of State for India had asked the

Viceroy to raise no less than an additional 100,000 troops by the

Spring of 1918 to fight the Turks. Only the cavalry would remain

on the Western Front until 1918, and the sappers and miners until

1919, clearing mines.

In the summer of 1916, Haig amassed over a million soldiers in the Somme for a major onslaught on the German lines. The Indian Cavalry would bear the brunt of the operation. In the first few hours alone British troops and their allies, with the Indians to the front, took nearly 60,000 casualties with 20,000 dead. Despite the casualties, Haig ordered the action to continue. The battle raged until mid-November. The total number of dead was 1.3 million. The allies had advanced six miles. Though reports in the newspapers continued for months, few mentioned the Indian Cavalry.

Hospitals

Great publicity was done by the British authorities regarding the hospitals provided for wounded Indian soldiers in England, the care to observe religious rites, and the amenities provided. It was even claimed that the King of England had handed over one of his palaces, the Brighton Pavilion, for conversion into a hospital. This was a blatant lie, since Brighton Council had been its owners for over 50 years. Nearly 120,000 carefully stage-managed postcards of the hospital were distributed and over 20,000 souvenir booklets sent to India. The reality, however, was otherwise. The Pavilion and other hospitals were surrounded by barbed wire. Kitchener's Hospital, the former Brighton Workhouse, was described in one letter home as "Kitchener's Hospital Jail." No English nurses were allowed to treat the patients, only to carry out supervisory roles. There was no fraternization. Outside activities were limited and under heavy supervision. Visits to the patients were only allowed with passes and under scrutiny, to guard against what were termed "Indian nationalists." Only those with the most severe injuries were returned to India. The others were sent back to the front. Self-harm and suicide were common. Letters home revealed many complaints about the food and the treatment. Many expressed the suspicion that the Indians were being sacrificed as "cannon fodder." Some urged their relatives at home: "Do not enlist!"

Massacre

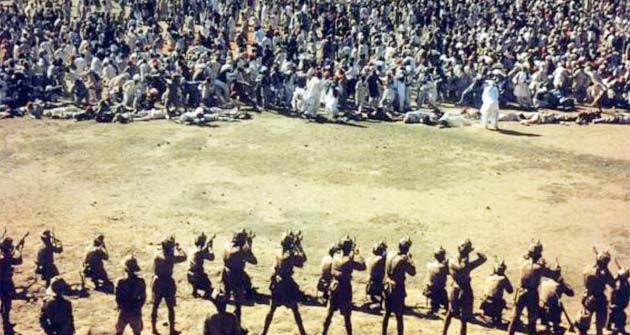

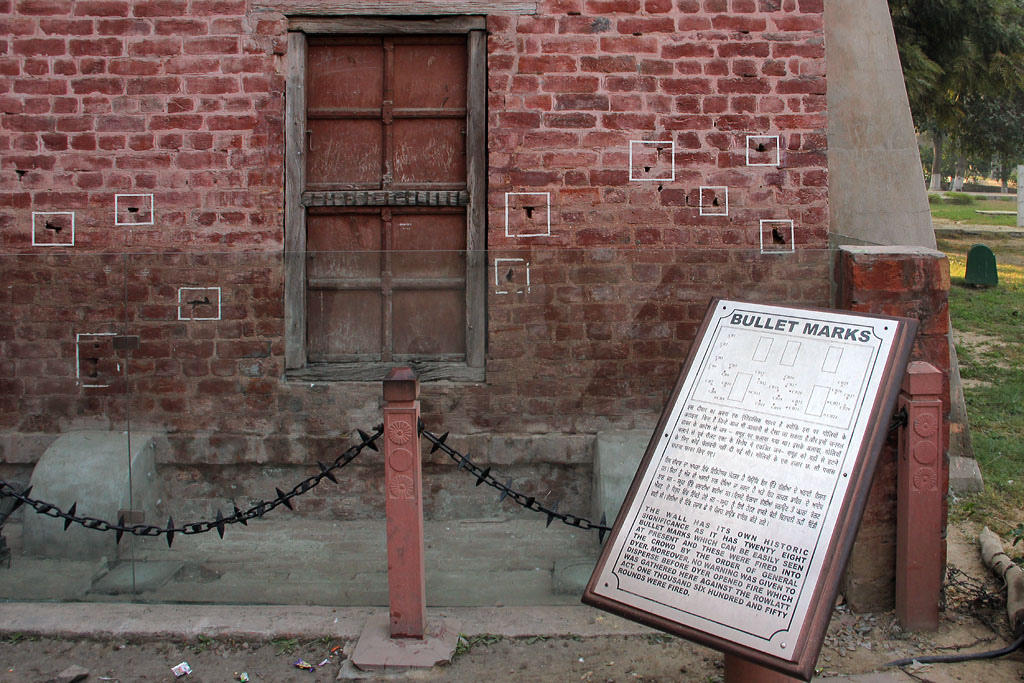

The war was brought to a close with the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the October Revolution in Russia the previous year being a major factor in bringing peace. The Peace Conference convened in Paris in January 1919, was to last six months, and conclude with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. India had three delegates at the Conference, the Secretary of State for India, Edward Montagu, the Maharaja of Bikaner and Lord Sinha. All three shared a vision of India eventually governing itself, but within the British Empire, with Sinha commenting that Britain must remain "the paramount power." Back in India the intellectual elite had backed the war expecting concessions as a reward for the sacrifices made. But they were to be bitterly disappointed. The Government of India Act of 1919 only consolidated colonial rule. The war had had a devastating effect on India. Crops had failed, prices were high and a spirit of unrest was growing. Famine had been declared in Central India. The greatest unrest was in the Punjab. Severe hardship was occurring in the cities. There was great anger at the seizure of foodstuffs for the war effort under the Defence of the Realm Act. War weariness gripped the region, which had sent the most combatants to the front. Villages were mourning the dead and tending the wounded. The response of the British Government was the Rowlatt Act, passed in London in March 1919. It banned public meetings and muzzled the press. It authorized in camera trials without jury. Persons suspected of revolutionary activity were imprisoned without trial for up to two years. Protests were put down by troops with lethal force. On April 11, 1919, General Reginald Dyer occupied Amritsar, imposing a curfew and banning all gatherings. A proclamation to that effect was read out on April 13. That day was the festival of Baisaki, the Sikh New Year. Crowds had gathered at the Golden Temple in a festive mood. Nearby was the enclosed park called Jallianwala Bagh. Thousands had gathered there peacefully at a rally to discuss the Rowlatt Act and recent police killings. As is now well known, Dyer brought armed troops in through the single narrow entrance to the park and opened fire on the crowd, ordering his troops to keep firing until their ammunition was exhausted. There was no escape. Around 1,000 were killed and some 1,500 wounded. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre shocked and enraged the country. Barely five months from the end of the war, in which 400,000 Punjabis had fought, this was Britain's reward. Dyer was unrepentant. The massacre was followed by the bombing of Punjab cities, the extension of martial law and further repression. In London, the report to the War Cabinet for that week barely mentioned the event, simply stating that there had been "trouble" at Amritsar where "troops were called in to restore order." No mention was made of the killings. It was not raised at the Peace Conference in Paris either. The troop ships returned to Bombay and Karachi. Bands

played

but there was no heroes' welcome. Too many had died. Too many were

crippled, blind or shell-shocked. Some hospitals for the wounded

and limbless were set up, but of little help to those returning

to remote regions. Crops had failed. Unrest was rife. A new mood

of nationalism was growing in the country. The heroes would now

be of the Independence or Freedom Movement. In the British

official histories of the war there would be little mention of

the Indian soldiers who had made such sacrifice. Note

|