|

Supplement

Centenary of the End of World War I British Movement of

• The Men

Who Said No British Movement of Conscientious Objectors The Men Who Said No

In the early 20th century, the concern of working people in many countries about the danger of an inter-imperialist war for the redivision of the world war was profound. Britain was no exception.

Long before the outbreak of World War I, thousands of people campaigned against the escalating signs of war and, finally, against the inter-imperialist war itself. Enormous pressure was put on the people to join the war in the name of high ideals of patriotism and loyalty to the British Empire. This made enemies out of those who did not espouse these values. The same was the case throughout the British Commonwealth, including Canada. Working people's resistance to war took many forms, including conscientious objection.

In

the

articles

below, TML Weekly

highlights the organized movement of conscientious objectors in

Britain, the men who courageously stood with their anti-war conscience

in the face of threats, bullying, imprisonment and death. They said No! and many, including a militant

women's movement, rallied to their just stand.

(With files from menwhosaidno.org, UK Parliament website) Opposition in Britain to the War

|

|

|

Besides this, once Britain officially declared war on August 4, 1914, the draconian Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed on August 8, 1914 which made active opposition to the war a criminal offence. DORA gave the government the power to suppress the activities of the anti-war movement and to attack the right to speak and to publish. Several leading anti-war activists, including the Scottish teacher and revolutionary John Maclean, were arrested and imprisoned as a consequence.

Despite this criminalization of dissent, opposition to the war and the government's policy of forced conscription was widespread. In April 1916, more than 200,000 people demonstrated in Trafalgar Square in London against conscription. Between May 1916 and the armistice in November 1918 in Britain some 20,000 men refused to be conscripted into the British army. Several thousand of them were imprisoned for their stand. Many felt that it was wrong to kill under any circumstance and that war was not the solution to any problem.

Besides the attempt to suppress the anti-war movement through DORA, with the conscription regime in place, from the moment men received the letters demanding they present themselves at a military depot, they were deemed to be soldiers and subject to military law. This stripped men of their civil liberties, negated their right to conscience and gave the army total control over their lives for an indefinite period.

Courageous Resistance in the Face of Draconian Military Justice

With conscription in place, some 2,000 Military Service

Tribunals were set up around Britain to question men who sought

to be exempted. Applicants had to fill in questionnaires making

their case. Exemptions could be given for a number of reasons

including conscientious objection -- on domestic grounds (people

with ill-health, unsupported children or elderly relatives), or

because they had important civilian jobs, such as doctors,

teachers, farmers and key industrial workers. Millions applied

for some kind of exemption and with this huge number of cases,

Tribunal hearings would usually spend only a few minutes on each

applicant before Tribunal members made their decision. Overall,

of those who applied for exemptions, some 800,000 applied for CO

status, and only 16,000 or two per cent of them were officially

granted this status.

The Tribunals were appointed by the local municipal council, typically about 25 men, rarely any women, with five to six being present for the actual hearings. Although they were supposed to be impartial, nepotism in the appointments was typical. Furthermore, many Tribunal members were biased against COs and the ever present military representative made sure there was no backsliding by other members. The military need for fighting men at the front was held to be paramount.

Although the Military Service Act included a

hard

fought for but ill-defined clause on conscientious objection,

many Tribunals simply did not understand they could grant

absolute exemptions to military service (with no conditions) for

COs and they often saw their role as making sure as many men as

possible were enlisted into the army. As a result, thousands of

COs were treated unfairly and many of them would suffer harsh

treatment in prison.

Death Sentences

In the early days of conscription, the army had no idea how to deal with stubborn, principled men who refused to obey any orders. Bullying and intimidation had failed and in May 1916, the army stepped up its threat when it shipped 50 COs from around Britain to France and sentenced 35 of them to death.

Assurances had previously been given that COs would not be subjected to the death penalty but the position of men who had been rejected by the Tribunal and sent to the Army as insincere in their objection was unclear. Did this mean that they were subject to army regulations, which prescribed death by shooting as punishment for disobedience on active service? No one knew.

Soon after the introduction of conscription, rumours about COs being sent to France to be shot began to circulate. "If they disobey orders of course they will be shot, and quite right too!" said Lord Derby, Director of Recruiting, as 17 men in Landguard Fort were released from their shackles on May 7 and put on a train to France.

On being told of this, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith immediately dispatched a message to the front forbidding any execution without the knowledge of the Cabinet or sending any further COs to France, but the army had ideas of its own. While the government was publicly denying that COs had been sent to France to be shot, the army, in a show of disregard of the elected civil authorities, dispatched a further batch of men to France who were told that they were going to be shot. They were marched to the train to the sound of the military band playing the "Death March."

By moving these COs to France and closer to the front line the army believed it could intimidate them into submission. It would give the army the pretext to say that the COs had failed "under active service conditions" and it would be free to summarily execute those who continued to "disobey orders."

After weeks of painful punishments and constant abuse, the COs -- now known as "The Frenchmen" -- were formally told: Continue to disobey and face the death penalty. By June, the Army was running out of patience. The Frenchmen were marched out in groups to a camp outside Boulogne within sight of the cliffs of Dover across the English Channel and told for a final time to obey orders. When they once again refused, their sentence was read out.

One of the COs Hubert Peet, later recalled, "I was number three on the list, and as I stepped forward I caught a glimpse of my paper as it was handed to the Adjutant. Printed at the top in large red letters, and doubly underlined, was the word 'Death.' I can hardly analyze the feeling that flashed through my mind as I caught sight of the word.'

"'The sentence of the court is to suffer death by being shot,' said the Adjutant. 'This sentence has been confirmed by the Commander in Chief' -- there was a long pause -- 'and commuted to ten years penal servitude.'"

All the COs were given the same long sentence, but they

had

escaped the death penalty and were sent back to civilian prisons

in Britain. At the last moment, political pressure and frantic

work at home by their supporters had saved their lives. The

resolve and determination of the threatened COs became a rallying

point for those in Britain and made it clear that their

resistance would not be broken by military means.

Image of conscientious objectors in

Dyce Quarry. Includes 24 of the 35 men who

were sent to France and sentenced to death. Image from Refusing to Kill

exhibition.

(menwhosaidno.org, UK Parliament website)

Organizing to Oppose Conscription and Defend Conscientious Objectors

Members of No Conscription Fellowship national committee on their way

to prison,

July 1916.

The No Conscription Fellowship (NCF) was formed to campaign against the imposition of compulsory conscription. Later, when this failed and conscription became law, the NCF provided support for conscientious objectors (COs) throughout Britain. As time went by, what stands to take in the various circumstances to affirm one's conscience required ongoing deliberation in the anti-conscription movement. The NCF provided a vital forum and converging point for COs and their defenders.

The NCF began to take shape in the autumn of 1914 when, Fenner Brockway -- editor of the strongly anti-war Independent Labour Party newspaper Labour Leader -- at the suggestion of his wife Lilla, called on all those who were not prepared to take part in military service to get in touch. There was an immediate and enthusiastic response. Following a national meeting the NCF was founded in November 1914. Its "Statement of Faith" declared it an organization of men "who will refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms, because they consider human life to be sacred and cannot therefore assume the responsibility of inflicting death."

|

|

Membership began with some 300 people but rapidly grew, such that by 1915 the NCF operations had to be moved to London from the Brockways' home in Derbyshire.

The NCF was organized meticulously, keeping records of every CO, the grounds of his objection, his appearance before tribunals, civil courts, courts martial, and even which prison or Home Office settlement they were in. They also maintained contact with COs, arranging visits to camps, barracks and prisons across the country. Pickets of prisons were held. The NCF also had a press department, which constantly sought to draw the attention of the public to what was happening to COs and the ill-treatment and brutality many were subject to. They also published leaflets and pamphlets and from March 1916 a weekly newspaper called The Tribunal. The Political Department briefed Members of Parliament (MPs) and drafted questions to Ministers. The NCF worked with two other organizations: the Friends' Service Committee (the Quakers) and Fellowship of Reconciliation.

Ranged against the NCF was the full might of the British state -- the police and the army -- as well as most churches and the jingoist press which whipped up public opinion against COs or 'conchies' as they were labelled. Immense personal pressures were put on COs not just by the state, but also by communities, neighbours, friends, even families. They also had to withstand the pressure to conform when isolated in barracks, army camps and prisons. Some men were shipped to France in May 1916 as the government and army attempted to break their resolve; some were actually sentenced to death although the sentences were commuted to 10 years hard labour. By the war's end at least 100 men died while under state control. Some suffered mental breakdowns. Altogether some 20,000 men refused to fight.

Women played a crucial part in the NCF. Firstly as mothers, sisters, wives, girlfriends and friends of the men who often had to face hostility from family and neighbours. Secondly as workers in the organization itself, especially as male members were gradually moved to prisons. These included Catherine Marshall, who acted as Parliamentary Secretary; Violet Tillard who worked in the Maintenance Department, acted as General Secretary for a period and was sentenced to 61 days imprisonment for refusing to tell the police who the NCF printers were; Ada Salter; Gladys Rinder; Joan Beauchamp who was also jailed twice; and Lydia Smith who worked in the Press Department.

The final convention of the NCF took place at the end of November 1919 at Devonshire House and was attended by over 400 delegates from branches all over the country.

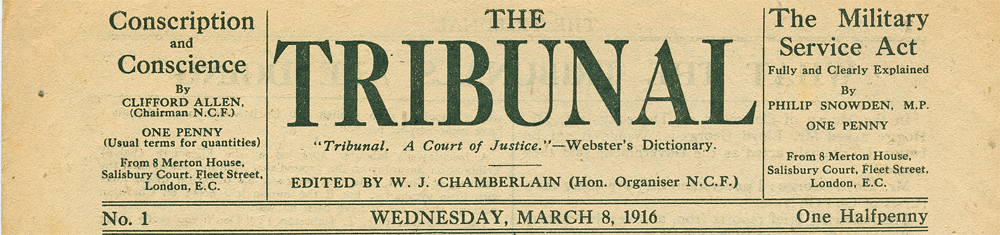

NCF Newspaper The Tribunal

The Tribunal was published weekly from March 1916 and at its height, had a distribution of over 10,000 copies.

It reported on the lives of COs -- from their motivations and reasons for objecting to war to their experiences at Tribunal, in prison and beyond. Named after the Military Tribunals to which the COs were subjected, The Tribunal was written clearly, and often movingly, with the intention of keeping COs and their thousands of supporters and sympathizers updated with the latest information in the struggle against conscription and militarism.

The Tribunal provided a vital service to COs all over the country, keeping them updated with the latest news, providing inspiration, guidance and examples of how an individual can successfully resist conscription. For men and women up and down the country, The Tribunal showed them on a weekly basis, that war could be resisted. Most COs found their experiences difficult, whether in a work camp, in prison or simply undergoing scorn and ridicule for their views. For these men, The Tribunal was a lifeline, linking them to the wider struggle.

The Tribunal also often played the role of advisor, suggesting to COs undergoing their tribunal hearings, court martial or magistrates court hearing, how they could best convince their jailers they were genuine men of principle. It also offered guidance on the types of work COs were expected to do -- alerting men looking at non-combatant service with the army, for example, that other COs were being forced to move armaments.

From 1916 onwards, the printers and publishers of The Tribunal -- many of them women -- were involved in a clandestine struggle against government censors. Their offices were raided repeatedly and office staff were followed by state agents, some were even imprisoned. The printing type was stolen and eventually the press on which The Tribunal was printed was confiscated and broken down for scrap iron. Though all of this, the remarkable editorial and publication staff of The Tribunal, with the support of their NCF colleagues, managed to keep the paper running.

The NCF's strong-minded and determined staff had thought ahead. They had a network of connections and sympathizers (some in other papers angry about press censorship), including two supporters who were skilled printers. Through these individuals, working in secret in a location as yet unknown, The Tribunal continued to publish.

(menwhosaidno.org)

Civil Service and Non-Combat Roles in

the Military for

Objectors

|

|

Under the Military Service Act and the Military Tribunal system, conscientious objectors (COs) could have recourse to alternatives to combat, depending on the circumstances people faced and their individual conscience, including whether they considered it necessary to be imprisoned to make their point. Thus in practice, conscientious objection took a number of forms.

With Britain at war and its economy organized for that aim, it could be difficult for COs to fully extricate themselves from activities that somewhere down the line contributed to the war. Some COs were agreeable to carrying out some form of civil service in Britain in lieu of taking part in combat, with or without a direct connection to the war, known as Home Office Schemes or Work of National Importance. Others were agreeable to some non-combat roles within the military, such as the Non-Combatant Corps, some were part of the Royal Army Medical Corps. There was also the Friends Ambulance Unit set up by the Quakers.

Non-Combatant Corps

Non-Combatant Corps (NCC) of COs arose from the Military Service Act which, in its provision for COs to be granted "Exemption from Combatant Service Only," created a new type of soldier by the thousands -- the official non-combatant. Non-combatant soldiers had existed in the army before 1916, often in the form of medical workers, but prior to conscription it had never been a problem on this scale, and never without the army having a specific reason for allowing men to serve in a non-combatant capacity. Once granted "Exemption from Combatant Service Only" by their local Tribunal hearing, COs would be expected to report to barracks, either directly to an NCC unit, or to a combatant one, there hopefully to be redirected into the NCC. From the army's point of view, the NCC had the aim of freeing up soldiers behind the lines from routine labour and logistics tasks to fight on the front lines. For a CO, being in the NCC meant clearly stating that he would not be forced to kill, but would provide support for the Army. The NCC was a compromise and often contradictory. What exactly constituted non-combatant work was determined by the COs' own principles.

Members of the NCC were definitively soldiers, but could not be made to carry or use weapons, meaning in effect that they could not be made to actively participate in the slaughter of war. To some, loading munitions was unacceptable, an example of directly contributing to the murder of another human being, but to others this line could be drawn far earlier -- perhaps refusing to construct a road to help soldiers get to the front more quickly. Though taking up an "alternative" to military service, they were still in the military, and work they carried out had to be approved under their own sense of what constituted killing in warfare. Strikes, work stoppages and slowdowns characterized much of the NCC's record as COs refused to take up work that could directly support the war effort.

Despite taking a different stand than those COs who went to prison, those in the NCC stood by those imprisoned and consistently protested and agitated for their better treatment and conditions.

COs in the Royal Army Medical Corps

Many COs suggested at tribunal hearings that they would be prepared to take on Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) work. As an organization dedicated to saving life, it is an explicitly non-combatant branch of the Armed Forces, and as such was seen to be an acceptable position for many COs. Tribunals were happy to "oblige," recommending that hundreds if not thousands of men should join the RAMC. However, there was no mechanism to implement such a recommendation by the tribunals. Ultimately, only one in 50 men recommended to the RAMC actually joined the corps. As well, the RAMC could not train the numbers of men recommended to it. Perhaps most importantly, no army institution would be content to be swamped with thousands of COs who could have the wrong influence on regular soldiers they came into contact with.

Volunteering for the RAMC did not necessarily mean an end to a conscientious objection to warfare. Throughout the war they had to continuously oppose attempts to force them into fighting units, despite having joined under a non-combatant agreement, even to the point of being court-martialled and imprisoned for this resistance.

Friends Ambulance Unit

British Quakers convened

themselves in London on August

7,

1914, to deliberate on their response to Britain's declaration of

war three days earlier. Outside the official sessions, a group of

Young Friends worked on the idea of an ambulance unit. They were

convinced that ambulance services would be woefully inadequate,

so that offering such services could save many lives. It became

operational by the fall of 1914, operating as the Home Service in

hospitals in Britain and the Foreign Service in France.

British Quakers convened

themselves in London on August

7,

1914, to deliberate on their response to Britain's declaration of

war three days earlier. Outside the official sessions, a group of

Young Friends worked on the idea of an ambulance unit. They were

convinced that ambulance services would be woefully inadequate,

so that offering such services could save many lives. It became

operational by the fall of 1914, operating as the Home Service in

hospitals in Britain and the Foreign Service in France.

Although primarily voluntary, the FAU would later provide COs a means to respect their principles of non-violence and avoid prison. In 1916, conscription provided a sudden influx of COs, and a General Service section was started to offer them alternative training, if required. It also helped organize other alternative work for COs who could not join the FAU.

Home Office Scheme

The Home Office Scheme was set up in August 1916 to deal with the "problem" of thousands of COs who were refused recognition by a Military Service Tribunal. Consequently they were forcibly enlisted in the army, refused to obey military orders, were court-martialled and clogged up civilian prisons.

All CO prisoners were taken to Wormwood Scrubs Prison in London or Barlinnie Prison in Glasgow, for COs in Scotland, where they were interviewed by the Central Tribunal, and, if found "genuine," would be offered admission to the Home Office Scheme. This entailed agreeing to perform civilian work under civilian control in specially created Work Centres/Work Camps. Refusal to accept meant returning to prison to complete their sentences, then returning to the army, where renewed disobedience would entail another court-martial and another prison sentence.

Work of National Importance

What was called "Work of National Importance" was an official alternative to military service to which COs could be assigned by a local Tribunal to secure exemption from conscription. It took the form of regular employment, but the mechanisms and rules of WNI ensured that it was also a punishment, and WNI was neither the easy nor the simple option. Accepting WNI meant accepting a part, however small, in the war effort as a "Nationally Important" industry was necessarily one that was vital in sustaining the country during the war.

A CO could not simply declare that he was exempt due to his work, the WNI option had to be secured explicitly through the Tribunal system. Provided that a CO could find (or would be found) WNI, then they would be exempted from the military for the duration of that work. Exemptions were decided on a case by case basis. Throughout the war despite frequent industrial manpower crises, no attempt was made to conscript COs into industry on a widespread and organized basis. COs were often left to their own devices to find WNI, and especially in the early months of conscription in 1916, could secure work in their local communities and report back to the Tribunal that granted them exemption. If the Tribunal approved, the exemption could be considered secure. If not -- and Tribunals frequently disagreed on what was and was not considered "Nationally Important" -- then the CO would be forced to find other employment, usually under a time constraint of 21 days.

The Tribunal system lacked oversight or a consistent way of dealing with WNI COs. It also left WNI exemptions open to appeals against them -- both from COs and the Tribunals themselves. The arbitrary nature of the Tribunal system caused significant hardship and difficulty for the COs it affected. Exemptions could be revoked, changed or qualified, with Tribunals withdrawing exemption for any infraction -- a wage they considered too high, or that a CO was working too close to home. Tribunals could rule that a CO would have to work at a certain distance from their home, usually done arbitrarily to make finding and keeping WNI a punishment.

Overall, around 4,500 COs were sent to do WNI, and they came from every single area, class and motivation that produced COs.

(menwhosaidno.org, Quakers)

Imprisonment

A group of Conscientious Objectors leaving Dartmoor Prison.

Many conscientious objectors (COs) ended up in prison. For some, this was a conscious choice made at the start of conscription to refuse participation in any activity they felt would contribute to the British war effort, whether in the Non-Combatant Corps or in the various Home Office Schemes. They were known as the Absolutists. For others, imprisonment was the ultimate destination they reached as their thinking developed and they considered what stand to take to be effective in opposing the war and conscription. Still others were imprisoned because the army had violated their right to participate in the military in non-combat roles and they had been court-martialled for refusing orders.

At the time of conscription in 1916, the notorious conditions of British prisons were only marginally less grim than at the end of the 19th century. Punishment was their overriding function. Many spent time in solitary confinement (today, extended periods of solitary confinement are considered a form a torture and barred under international law). Those sentenced to hard labour were given pointless and arduous tasks. To a lesser extent the slave labour of those imprisoned was also used to generate revenue for the state. The diet was poor, cells were cold and often damp. The COs' experience in prison was not dissimilar to that of other inmates with the exception of the fact that their "crime" was to refuse to commit murder. These conditions were shocking to many COs, many of whom challenged the system. After the war, some would go on to work and campaign for prison reform.

A common occupation for COs in their solitary cells was to sew mailbags. As the skin hardened on their fingers some began to wonder what precisely was the difference between sewing mailbags in a solitary cell and doing some other work on a Home Office Scheme. For example, after his third court-martial in May 1917 and a sentence of two years hard labour, Clifford Allen wrote to the No Conscription Fellowship (NCF) from his cell in Parkhurst camp on Salisbury Plain explaining his thinking. He also wrote a letter to Prime Minister David Lloyd George giving notice of his intention:

Before I am removed to prison I think it is right to make known to you that, like other men similarly situated, I have recently felt it my duty to consider carefully whether I ought not for the future to refuse all orders to work during imprisonment. I have decided that it is my duty to take this course. This will mean that I shall be subjected to severe additional punishment behind prison doors. Provided I have the courage and health to fulfil this intention, I shall have to spend the whole of my sentence in strict solitary confinement in a cell containing no article of any kind -- not even a printed regulation. I shall have to rest content with the floor, the ceiling and the bare walls. I shall have nothing to read, and shall not be allowed to write or receive even the rare letters or visits permitted hitherto, and shall live for long periods on bread and water.

Such a stand was said to have caused consternation for the National Committee of the NCF, which had only just began persuading COs from work striking. It felt that its campaign to secure socially useful work for COs through the Home Office Schemes could be jeopardized. Nonetheless the NCF published Allen's letter in The Tribunal which was followed by a vigorous correspondence. Some felt that "To win through we must succeed in influencing the heart and mind and conscience of the nation and the authorities. We have to convince them: we cannot threaten or compel them. Our methods must be those that will stand the test of time." Despite such serious and deeply felt differences during its years of work, the men and women of the NCF continued to effectively work for a broadly common cause.

The Wakefield Experiment

The Wakefield Experiment was one of the last, and shortest-lived, attempts made by the government to encourage Absolutist COs to compromise on their principles. It underscored the harsh treatment of the COs and the violation of their rights, and the unjust nature of Britain's participation in the war as a whole.

August and September 1918 were awash with rumours that a new way of dealing with Absolutist COs was on the horizon. Many "two year men" had begun to be released from prison, especially those whose health had been destroyed by prolonged imprisonment. Change seemed to be in the air, and with the war clearly entering its terminal stages, COs began to look forward to an imminent release.

The Wakefield Experiment was devised to prolong the imprisonment of COs, and rapidly became a political embarrassment for the government as the war wound to a close. It had been planned as a way to involve COs in their own punishment, allowing them to essentially manage their conditions in prison, and therefore keep them locked up without significant protest until the government saw fit to release them. Though a significant compromise on the part of the government, its purpose was merely to be a stop-gap measure intended to mollify many of the concerns and protests that had built up over the past two years.

It began with men who were long-standing COs who had already served multiple sentences being gathered into groups in prisons around the country. On Friday, August 30, 1918, the first of these groups were moved and ten Absolutist COs in Durham Prison, all having served more than two years, were told that they were to be transferred to Wakefield Civil Prison. These men were given no choice, and little chance to inform anyone of their whereabouts. Prison officials at Durham had no idea of the conditions at Wakefield, and for many, it would have seemed to be simply another prison transfer. More men would be transferred from Dorchester prison.

Initially, conditions seemed better at Wakefield. Locks had been removed from the prison doors and COs had freedom of movement within the prison itself. They could even freely buy writing materials and tobacco with a little pocket money. They were allowed to wear civilian clothing, allowed to see visitors and accept parcels, letters and food from them. The conditions seemed good -- not a full release, but certainly better than prison. The mystery was in why it had all happened -- and in the selection of certain men for transfer. In September, around 120 men were brought in small groups to Wakefield, and handed over to the wardens, who had barely any more information on the experiment than the prisoners themselves.

The relaxed conditions were earmarked as "temporary" and though COs were freely allowed to report on them from inside, no clear plan seemed to have been made for what the COs would do, how they would be treated, or how the prison would be run. They were initially assigned work to maintain the prison and set up a canteen, an agreeable change from the hard labour of other prisons, and the rules that governed their lives were lax. COs had dedicated free time and working hours and could smoke fairly freely, in return for agreeing to not damage prison property and diligently work at assigned tasks

From the point of view of the Governor (and government), the conditions of the scheme would have seemed reasonable. If long-serving COs could expect similar treatment around the country, it must have appeared that the problem of the Absolutists was at long last solved.

The Wakefield Revolt

The largely liberal rules at Wakefield did not meet with universal support among the men experiencing them. Many COs wrote to the NCF and other organizations explaining their position. There seemed to be no clear plan of what to do with the COs held there, and in discussion together the COs decided to wait it out in order to see exactly what kind of system would be drawn up around them. It seemed in many ways similar to the Home Office Scheme, except with no written agreement and no freedom to travel outside of the prison.

Work details were light, and with no locks on prison doors and plenty of free time, the imprisoned COs held long discussions over what they would and would not do while at Wakefield. Opinion was divided as to why COs were there in the first place -- either to put them under industrial conscription, or to segregate these "Absolute-Absolutists" from the general population, or perhaps even to acknowledge that the prison system had failed. They agreed that they would not submit to prison discipline, would not be put to work they had not agreed to and began to plan a strike. After more than two years of prison, Absolutists were not about to compromise now -- even in the seemingly limited way demanded of them at Wakefield.

It only took one more week for mystery to resolve into fact, and for the Wakefield Experiment to come crashing to an end.

After a period of settling in, the Wakefield men had taken it upon themselves to organize and run the prison as they wished. Committees divided the labour of prison upkeep and cordially invited the wardens to help if they wished. The Governor, with no instructions on what to do, allowed the Chairman of the Committee, Walter Ayles, to represent the official Home Office plan for the prison to the assembled men. Ayles presented the rules and regulations on how COs in Wakefield would be expected to work and live on September 16. There had been no great threat of exceptional mass punishment, simply that if the rules of the new scheme were not followed, men would be returned to prison. The position was simple. In exchange for their work, COs would stay in Wakefield and be managed, in all essential respects, by themselves.

Two days later, with a resounding rejection of the principle of compromising conscience for better conditions, all but six of the 125 COs were back in locked cells, soon to be returned to the prisons they came from.

The final piece was the creation of the "Manifesto of the Absolutists at Wakefield." Not only had the COs held there organized and discussed their thoughts, but had formed a committee which wrote, drafted and distributed a clear statement of intent. The Manifesto signalled the clearest statement of the Absolutist position. Despite better conditions, no manner of compromise would fulfil the aim of the Absolutists: unconditional liberty and discharge from the army. The Manifesto explained that the government: "take for granted that any safe or easy conditions can meet the imperative demands of our conscience. No offer of schemes or concessions can do this. We stand for the inviolable rights of conscience in the affairs of life."

The 123 men at Wakefield refused any form of compromise with the government and demanded either release, or a return to prison. No change in their circumstances could win them over and put them to work.

The position outlined in the Manifesto had been the Absolutist stance since before conscription had become law, and the rejection of the Wakefield Experiment was the last attempt by the government to subvert or undermine it. The Wakefield men returned to prison, and the incarceration of COs continued as before.

Plaques to conscientious objectors: Left in Tavistock Square, London

and

right, in Glasgow, Scotland.

(menwhosaidno.org)

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca