|

March 24, 2018 - No. 11

Supplement

Bill C-59, the National Security and Intelligence

Review

Act

PDF

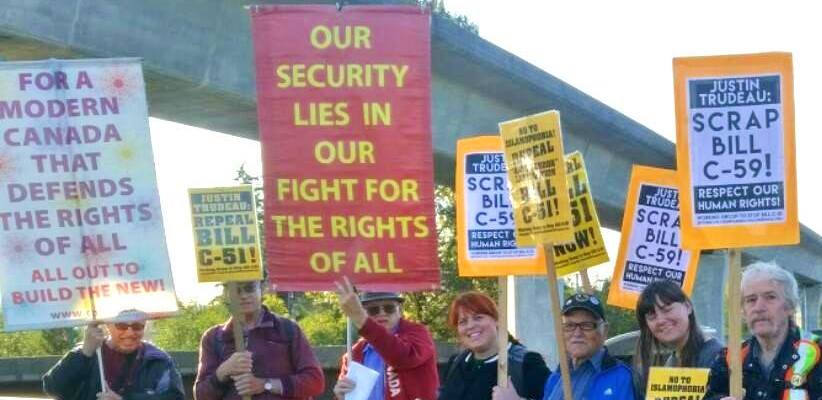

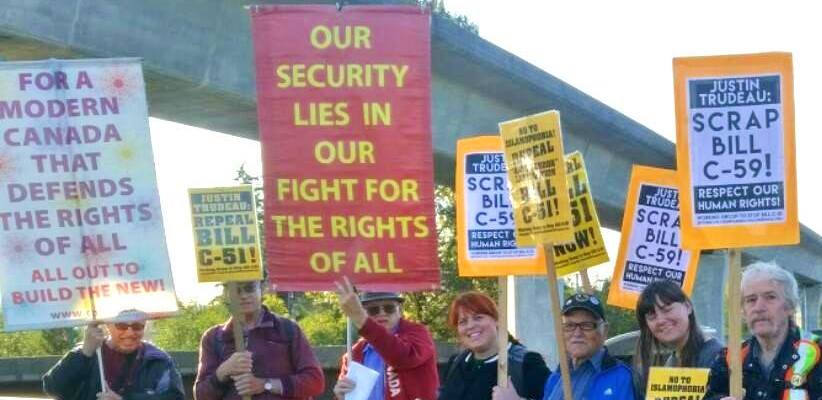

Vancouver picket, October 14, 2017, demands Bill C-59 be scrapped, and

Bill C-51 be repealed.

Hearings

of

Standing

Committee

on

Public

Safety

• Concerns

About Dangerous Legislation Raised

• Minister, Intelligence, Police and Spy

Agencies Address Committee

For Your Information

• What the Bill Contains

Hearings of Standing Committee on Public

Safety

Concerns About Dangerous Legislation Raised

During its hearings the Standing Committee on Public

Safety was addressed between December 5, 2017 and February 8, 2018 by

organizations they invited to speak about their opinions of the

legislation. Below are excerpts of concerns raised by civil liberties

and rights organizations, advocacy groups, groups representing lawyers

and a number of academics.

Civil Liberties Organizations

Cara Zwibel, Acting General Counsel, Canadian Civil

Liberties Association:

"While

this

new

bill

has

partially

addressed

some

of

Bill

C-51's

constitutional

deficits,

it

has certainly not resolved all of them."

[...]

"...the

definition

of

'threats

to

the

security

of

Canada'

that

triggers

information

disclosure

remains unduly broad and circular. It is not

clear why this definition is so much broader than the one included in

the [Canadian Security and

Intelligence

Service (CSIS)] Act,

and we remain concerned that constitutionally protected

acts of advocacy, protest, dissent, or artistic expression,

particularly by environmental and Indigenous activists, will continue

to be swept up in the process."

[...]

"....the

list

of

[threat

reduction]

measures

set

out

in

proposed

section

21.1(1.1)

only

require

a warrant where CSIS determines that they may

violate the law or limit a Charter right. A warrant should be required

in any case where these measures will be pursued by CSIS. It is vital

that the determination of whether a law is being violated or a Charter right limited not be left

solely to CSIS."

Concerning the changes to the Secure Air Travel Act she

said:

"The process by which individuals are placed on the [No-Fly List]

remains opaque, and proposed redress mechanisms are inadequate.

Bill C-59 also fails to correct the flawed appeals procedure,

which parallels the system in place for security certificates

prior to the Supreme Court's Charkaoui

decision in 2007.

[....] The current process allows the use of hearsay and secret

evidence, without access to a special advocate able to test that

evidence or to represent the interests of the listed person."

Lex Gill, Advocate, National Security Program,

Canadian Civil Liberties Association:

"...the

proposed

active

and

defensive

cyber-operations

aspects

of

the

[Communications

Security

Establishment]

CSE's

mandate

essentially allow the Establishment to engage in secret and

largely unconstrained state-sponsored hacking and disruption. The

limitation of not directing these activities at Canadian infrastructure

is clearly inadequate given the inherently interconnected nature of the

digital ecosystem. Such activities are also bound to impact the privacy

expression and security interests of Canadians and persons in Canada,

and may threaten the integrity of communications tools such as

encryption and anonymity software that are vital for the protection of

human rights in the digital age."

[...]

"CSE's

cyber-operations

activities

involve

no

meaningful

privacy

protections,

require

only

secret

ministerial

authorization,

and

involve only

after-the-fact review."

[...]

"Bill

C-59

exacerbates

this

privacy

risk

by

creating

a

series

of

exceptions

for

the

collection of Canadian data, including one which allows its

acquisition, use, analysis, retention, and disclosure, so long as it is

publicly available. This definition is so broad that it plausibly

includes information in which individuals have a strong privacy

interest, and potentially allows for the collection of private data

obtained by hacks, leaks, or other illicit means. Furthermore, it may

encourage the creation of grey markets for data that would otherwise

never have been available to government -- a client with deep pockets.

The government has failed to demonstrate why this exception, as worded,

is necessary or proportionate, or what risk it is meant to mitigate in

the first place."

"We don't believe that ministerial authorization

through the Minister [of Defence] and

the Minister of Foreign Affairs is sufficient. We

would prefer to analogize these types of powers to the disruption

or reduction powers in the CSIS Act.

We

note

that

there

is

a much

more rigorous system for oversight and prior authorization in

that context."

Micheal Vonn, Policy Director, British Columbia

Civil

Liberties Association:

"We

know,

not

least

from

years

of

reports

from

the

CSE

commissioner,

that

disputes over the interpretation of legal standards and definitions

have been of ongoing concern, and national security activities in

general are plagued with the "secret laws" problem of having words in a

statute or directive interpreted in sometimes obscure or deeply

troubling ways, and ways that may not be unearthed for years."

[...]

"Canadian

datasets

--

which,

we

need

to

remember

--

are

expressly

defined

as

datasets

that contain personal information expressly acknowledged as

not directly and immediately relating to activities threatening the

security of Canada. The test for their acquisition is simply that the

results of their querying or exploitation could be relevant and that

this assessment must be reasonable. It may be argued that this vast

scope for bulk data collection is at least mitigated by the requirement

for judicial authorization for the retention of those datasets. But

rather than providing significant gatekeeping, this authorization

simply compounds the effects of the very low standards that lead up to

it. Personal information that does not directly and immediately relate

to threats to the security of Canada is allowed to be collected if it

'could be relevant,' if this assessment is 'reasonable,' and if the

judge then decides that the dataset can be retained on the standard of

'is likely to assist.' These, then, are the thresholds of what most

Canadians would call mass surveillance, and we believe most Canadians

would reject these thresholds as shockingly low standards... The

proposed standard represents a mass erosion of the privacy protections

from the strict necessity standards that currently apply. We recommend

that the CSIS bulk data provisions be revised to be expressly within

the strict necessity standard, and not in exception to it, and that the

criteria for bulk data collection, such as that fashioned by [the

Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC)] as

implicitly principled and workable, be set out within the legislation."

Alex Neve, Secretary General, Amnesty International

Canada:

"Without adequate safeguards and restrictions, overly

broad national

security activities harm individuals and communities who pose no

security threat at all. In all of these instances, the impact is

frequently felt in a disproportionate and discriminatory manner by

particular religious, ethnic, and racial communities, adding yet

another human rights concern."

[...]

"Currently, other than the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act,

none of Canada's national security legislation specifically refers to

or incorporates Canada's binding international human rights obligations

[...] Our first recommendation, therefore, remains to amend Bill C-59

to include a provision requiring all national security-related laws to

be interpreted in conformity with Canada's international human rights

obligations."

[...]

".... there needs to be specific prohibition of

the fact that CSIS will not involve threat reduction of any kind that

will violate the Charter or

violate international human rights

obligations."

[...]

"Bill C-59 also fails to make needed reforms to the

approach taken to national security in immigration proceedings. There

were very serious concerns about Bill C-51's deepening unfairness of

the immigration security certificate process, for instance, withholding

certain categories of evidence from special advocates."

Tim McSorley, International Civil Liberties

Monitoring Group:

The group was not invited to testify but

was brought by the group OpenMedia who believed they needed to be

heard:

"We

maintain

our

fundamental

opposition

and

call

for

the

repeal

of

the

no-fly list regime."

[...]

"We're

concerned

that

the

way

[the

Security

of Canada Information Sharing Act] SCISA is currently

worded, and how [the Security of

Canada Information

Disclosure Act]

SCIDA eventually

will

be

worded,

will

continue

to

pose

a

threat to legitimate dissent

and protestors' actions in Canada by including critical infrastructure

as it's currently defined."

[...]

"...for

the

proposed

CSE

Act

and

CSIS,

proactive

roles

should

be

put

in place

around the disclosure of foreign intelligence-sharing, as well as

around SCISA and SCIDA, and that we have clear definitions on what

foreign information-sharing is taking place and how it can take place."

Dominique Peschard and Denis Barrette,

Spokespersons,

Ligue des droits et libertés:

"It

is unacceptable for CSIS to be authorized to compile datasets on

Canadians. There are no limits on the data that CSIS can compile,

provided that the data is considered 'public.' Judges may approve the

compilation of other datasets based on a very weak threshold. The only

requirement is that the data 'is likely to assist' CSIS."

"These provisions make it legal for CSIS to continue to

spy and compile dossiers on protest groups, environmental protection

groups, Indigenous groups and any other organization that is simply

exercising its democratic rights. CSIS can count on the support of the

CSE, which is also authorized to collect, use, analyze, retain, and

disclose publicly available information, and whose mandate includes

providing technical and operational assistance to agencies responsible

for law enforcement and security. These datasets also pave the way for

big data and data mining, which in turn leads to the compilation of

lists of individuals based on their risk profile. We are opposed to

this approach to security, which places thousands of innocent people on

suspect lists and targets Muslims disproportionately. Bill C-59 allows

CSIS to continue to address threats through active measures such

as disruption. These measures can limit a right or freedom guaranteed

under the Canadian Charter of Rights

and Freedoms if so authorized by a judge. It is important to

note that this judicial authorization is granted in secret and ex

parte, so that the persons whose rights are being attacked

cannot

appear before the judge to plead their 'innocence' or argue that the

measures are unreasonable. They may also be unaware that CSIS is behind

their problems, which would make it impossible for them to lodge a

complaint after the fact. These powers recall the abuses uncovered by

the Macdonald Commission, such as the RCMP stealing the list of PQ

members, burning down a barn, and issuing fake FLQ news releases to

fight the separatist threat. We are therefore strongly opposed to

granting these powers to CSIS."

Their recommendations include:

- the Secure Air

Travel Act be repealed and any no-fly list be destroyed;

- that 'strict necessity' be

the threshold for

disclosing and receiving information under the Security of Canada Information Sharing Act;

- that CSlS be stripped of

the power to address threats

through active measures such as disruption.

Concerning the National Security and Intelligence

Review Agency, they recommend that "the agency must have the material,

human and financial resources needed to carry out its mandate."

Other recommendations include that "the agency must be

clearly seen as an independent organization that also has expertise and

whose mandate is to be accountable to the public. We think that what's

wrong about Bill C-59 is that, under it, the agency would report much

more to the department and the government than to the people on the way

the agencies conduct their business. Bill C-59 could be amended to make

the agency operate more as a watchdog that reports to the public on the

way

the agencies respect rights in carrying out their mandates."

Advocacy Groups

Ihsaan Gardee, Executive Director, National Council

of

Canadian Muslims:

"This law goes too far. It virtually guarantees

constitutional breach, and it offers inadequate justification. It

strengthens the security establishment when the evidence available

gives every indication that the institutions carrying out national

security intelligence gathering and enforcement mandates are in

disarray, rife with bias and bullying from the top down. Oversight of

those agencies is not sufficient. Real reform is necessary."

[...]

"Over the last 15 years we have seen three separate

judicial inquiries, numerous court rulings, out-of-court settlements,

and apologies that acknowledged the constitutional violations committed

against innocent Muslims by national security intelligence and

enforcement. Canadian Muslims are not only disproportionately affected

by these errors and abuses, but we also bear the brunt of social impact

when xenophobic and anti-Muslim sentiment surges. [The National Council

of Canadian Muslims] agrees with the

plurality of experts who state that more power to security agencies

does not necessarily mean more security for Canadians. National

security mistakes not only put innocent people at risk of suspicion and

stigma, but also divert attention away from actual threats and obstruct

effective action to promote safety and security. At the same time that

Alexandre Bissonnette was dreaming up his murderous plot to attack a

Quebec City mosque, the RCMP were "manufacturing crime," according to

the BC Superior Court judge in the case against John Nuttall and

Amanda Korody. They were Muslim converts and recovering heroin addicts

living on social assistance, whose terrorism charges were stayed last

year after a court found they had been entrapped by police. Bill C-59

strengthens the security establishment but does not address the

security needs of Canadian Muslims. While the idea of prevention is

laudable, any potential benefit from this approach will be negated by

the incursions on Charter

rights that disproportionately affect members

of our community, and which will continue to happen under the guise of

threat reduction, information sharing, and no-fly listing."

[...]

"For many young Canadian Muslims, the documented and

admitted involvement of intelligence and enforcement agencies in

rendition and other human rights abuses, and the complete lack of

accountability and perceived impunity that have been created as a

result, have bred a lack of confidence in the Canadian security

establishment."

[...]

"The security agency's loss of trust within Canadian

Muslim communities has been exacerbated by the lack of accountability

for past wrongs committed against innocent Muslims. While the

government has concluded significant settlements and made apologies, no

one from within those agencies has been held to account. To the best of

our knowledge, there has been no disciplinary action and no public

acknowledgements. Instead of accountability, some of those involved in

the well-known torture case of Maher Arar have even been promoted

within the agencies. At best, there was individual and institutional

incompetence in the security agencies. At worst, it was gross

negligence or bad faith. Neither is acceptable and the taxpaying

Canadians who fund these agencies deserve better. The lack of

accountability projects a culture of impunity within the Canadian

security agencies that reinforces the insecurity Canadian Muslims

experience. The problems with CSIS will not be mitigated by Bill C-59.

No amount of administrative oversight can cure the systemic ills. These

agencies need reform.

"We do not see any attention given in this proposed

legislation to the real impact that bias in national security has in

producing insecurity and harm within our communities. Without a clear

statutory mandate and direction from our government, we do not believe

that civil society alone can change the culture within CSIS and other

security agencies. We are willing to help, but that burden cannot fall

only upon us."

Faisal Bhabha, Legal Adviser, National Council of

Canadian

Muslims:

"First, we are asking that the no-fly list, formerly

known as the passenger protect program, be ended. We found that it

continues to cause serious damage to Canadian families and fails to

provide effective remedy or recourse, as you're going to hear from our

colleague beside me."

[...]

"Our view remains that no amount of tinkering can solve

the underlying problem, which is that the no-fly list is one of the

most damaging instruments of racial and religious profiling currently

in place in this country. It is the national security analogue to

carding in the urban policing context. Since its implementation, it has

caused so much damage without any proven or demonstrable benefit that

we simply cannot justify it in our rule of law democracy. It was an

interesting experiment, but its time has come to an end. What Canada

needs is not a list of banned flyers, but rather stronger investigative

and intelligence work so that people who present actual risks or who

have committed actual crimes are dealt with through the criminal

justice system."

[...]

"The second recommendation is to reform CSIS. With

respect to CSIS, we hold that it cannot be given additional powers,

given the current lack of faith and trust in the institution on the

part of many Canadians. There's simply too much evidence of systemic

bias and discrimination to ask Canadian Muslims and our fellow citizens

to trust that any new powers will not be exercised improperly and

discriminatorily. In fact, all of the evidence suggests that any new

powers will be exercised improperly and discriminatorily. As has been

mentioned, abuses in national security disproportionately affect

Canadian Muslims, though not only Canadian Muslims, and this is not a

coincidence. What is needed is a thorough culture shift within the

national security agencies before Canadians can trust that bias and

stereotypes are not driving investigations and will not shape the way

the proposed new powers to disrupt are deployed."

Zamir Khan, one of the parent founders of No-Fly

List

Kids:

"I am simply a Canadian citizen and a father, here to

testify to the harmful impact that can be enabled by gaps in

legislation and when intelligence gathered by our own security

agencies is applied in a haphazard manner."

[...]

"Canada's no-fly list was implemented in 2007 with a

design that included, in the words of our current Minister of Public

Safety and Emergency Preparedness, 'a fundamental mistake.' That flaw,

which persists today, is that verifying whether passengers are

potentially listed persons is delegated to airlines and done solely

based on their name, and this is despite both booking information and

the Secure Air Travel Act

watch-list containing additional identifiers such as date of birth."

[...]

"Statistics about the program and its effectiveness

have not

been shared since its inception in 2007 when the transport

minister disclosed that there were up to 2,000 names on the list.

Our group has been contacted by over 100 affected families,

representing the tip of the iceberg. The vast majority of

encumbered travellers are unaware of the source of their

difficulties by virtue of the Secure

Air Travel Act explicitly

prohibiting the disclosing of any information related to a listed

person. However, based on the names of the falsely flagged

individuals we know of, and the number of Canadians who share

those names, we conservatively estimate that over 100,000

Canadians are potential false positives when they fly."

[...]

"My three-year-old son, Sebastian, has been treated as

a

potentially listed person since his birth. That means, for the

first two years of his life, Sebastian was young enough, in the

eyes of travel regulations, to be considered a 'lap-held infant'

who didn't require a seat on the flight, but old enough to be

flagged as a possible security threat."

[...]

"That stigmatization has been described by the Minister

as a

traumatizing experience for them and their families. When the

children grow into teenagers and young adults, particularly young

men, their innocence becomes less obvious. As our group has

heard, their delays become longer and the scrutiny more intense.

This has meant that some families have missed flights and the

kids shy away from air travel for fear of stigmatization. This is

not a future I want for my son. The Secure

Air

Travel

Act permits the Minister to enter into agreements with foreign

nations to

disclose our watch-list to them. For example, a working group was

established in 2016 to share our no-fly list with the United

States. The prospect of this data being shared internationally is

troubling to our families, who have experienced frightening

ordeals of being detained and questioned or having passports

confiscated while travelling abroad. Indeed, my wife and I are

concerned about the treatment that awaits our family should we

travel outside of Canada, given what already happens

domestically."

[...]

"In January 2016, the Minister emphasized to airlines

that

children under the age of 18 did not require additional

screening. However, as was reported by CBC, the result was Air

Canada reiterating to their employees that all matches to the

list must have their identities verified in person regardless of

age. In June 2016, the government announced the Passenger Protect

Inquiries Office, or PPIO, designed to assist travellers who have

experienced difficulties related to aviation security lists. Our

group is not aware of a single family for whom the PPIO has been

able to resolve their case. To the average Canadian, a resolution

would mean permanently clearing someone who is falsely flagged.

The PPIO considers recommending signing up your child for an

airline rewards program or applying to the U.S. Department of

Homeland Security's redress system as a resolution. For those

flagged by the Canadian list like my son, a U.S. redress number

does not help. Airline rewards programs are an inconsistent and

flawed band-aid that the Minister has called a stopgap measure.

It's not good enough."

[...]

"[Our] group has secured letters from 202 Members of

Parliament, constituting two-thirds of the House of Commons, all

calling for the swift establishment of a redress system. There

appears to be all-party support for getting this done, but that

brings me to the bad news. On reading the proposed amendments to

the Secure Air Travel Act

contained in Bill C-59 it is apparent

that, although the bill takes a small step toward the

establishment of a redress system, it falls short of actually

establishing the system."

[...]

"Bill C-59 ... does not come close to setting out the

details of

a

redress system for people who are falsely flagged by the list. My

final point is that we are not asking the government to reinvent

the wheel. We need to look no further than our closest neighbour,

the United States. We have attached screenshots of booking

information for the same passenger travelling from Canada to

Halifax and New York, with a Canadian airline, Air Canada. As you

can see, the technology is already there for the passenger to

input their redress number when travelling to the United States

and be cleared at the time of booking."

Laura Tribe, Executive Director, OpenMedia:

Ms Tribe described OpenMedia as "a community-based

organization committed to keeping the Internet open, affordable, and

surveillance-free."

"I believe the active cyber operations, particularly

the ones geared at deploying tools abroad, pose a large security risk

for Canada in the way that they could be exploited."

[...]

"I think that once you have those powers in a very

opaque system where it's difficult to build in the transparency

mechanisms, it's hard to see how we can trust a system that we

consistently see being misused around the world. Our concern is not

that we think that the current government is immediately about to

deploy all of these weapons. It's that we're building the powers

without any justification to prove that we need them."

Responding to a question about reports of information

sharing between the RCMP and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, Tribe

said: "I think one of the big concerns we have is that we don't know,

or have any information about, how many information-sharing agreements

Canada has. We don't know whom they're with. We don't know what all of

them are about. When we give our information to the Canadian government

or it's being collected, we don't know where it could end up.

Conversely, when we take part in agreements with other countries, we

don't know how that information could end up back in Canada. One of the

concerns we have, and one that our community continues to express, is

feeling that no matter what that information is, eventually anyone

can get it within the Five Eyes agencies or within any of the related

countries' departments. Once it's in one dataset, it's in everyone's."

A committee member who argued that Canada needs to have

an "offensive [cyber] capability" asked how

"this or any Canadian government [should] guard itself from the very

real threats that exist in the cyber network or cyber sphere." Tribe

responded, "The biggest concerns we have are that there aren't checks

and

balances in place in the way that the proposed CSE Act is currently

worded.... Fundamentally, though, we are concerned that the scope

is too broad, that it lets CSE do too much without the accountability

and checks and balances needed to make sure it's used only if someone

is targeting something like our energy infrastructure."

[...]

"The clarifications are not there to provide the trust

that Canadians need. We weren't consulted on it. We were never asked in

the consultation what we thought about giving CSE new powers. I think

that's where our community's concern comes from."

Lawyers' Organizations

Peter Edelmann, Member-at-Large, Immigration Law

Section, Canadian Bar Association:

Edelmann said that despite "generally supporting" the

proposed new

legislation, the Canadian Bar Association is of the view that "The

breadth of the definition of an 'activity that undermines the security

of Canada' in section 2 is still very broad and notably it's different

from the definition in the CSIS Act

of 'threats to the security of Canada.' Having two definitions is not

helpful. It's confusing and it doesn't provide a clear mandate for

national security agencies and in particular for an oversight or review

agency. I would also note in passing that the amendment to the

exception in section 2(2) of the [Security

of

Canada

Information

Sharing

Act] is troubling as it actually

substantially reduces the protection under the current version. Several

legitimate political activities might be seen on their face as

undermining the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Canada. In the

past, we've recommended that there be one coherent, clear definition of

"national security" and we continue to be of that view. It's also

unclear whether certain other activities fall under the definition of

"national security" at all. The problem is particularly stark with the

Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), and we've expressed concerns

about this

lack of independent review of the CBSA in several past submissions.

CBSA remains one of the largest law enforcement agencies in the country

and has no independent oversight or review at all."

[...]

With respect to CSIS, we continue to have concerns

around the disruption powers. In particular, giving kinetic powers to

CSIS comes away from the mandate of creating CSIS in the first place,

after the McDonald Commission.... We continue to have concerns similar

to those we've had in the past with respect to these warrants limiting

Charter rights in that context.

Faisal Mirza Chair, Board of Directors, Canadian

Muslim

Lawyers Association:

"In particular, this bill does not address a key area

of security, the legal threshold for searches of digital devices at the

border."

[...]

"[M]y concern about what's missing from Bill C-59 is

that there needs to be some statutory guidance on when the CBSA may

search digital devices at the border. We can debate and go over at

length the fact that the bill has made progress with respect to

balancing individual rights with state interests, but the reality on

the ground is all of that can be circumvented by searches of

individuals' digital devices at the border. The Customs Act needs to be revisited

and reviewed. It is legislation from the 1980s, when digital devices

were not the norm, and it contemplated searches of people's luggage.

The use of data collection is the future of national security and the

devices that people carry with them obviously are integral in terms of

preserving a balance between individual interests and state interests

and in protecting our security. In today's era, most people travel.

Returning Canadians can easily have their digital devices searched

without restriction. A better legal threshold that reflects the nature

of the technology needs to be established. Currently it's the position

of customs and the government that there is no legal threshold to

search individuals' cellphones, laptops, etc., when returning at the

border. Even with a reduced expectation of privacy in that context, it

becomes critical that there at least be some legal threshold;

otherwise, the provisions in the Criminal

Code or amendments to the Immigration

and

Refugee

Protection

Act or amendments to try to protect

information sharing become easily circumvented when individuals are

coming back through the border with no protections whatsoever."

Regarding the listing of entities on Canada's Terrorism

List: "The difficulty is that organizations whose assets have then been

stripped and frozen have no ability to hire counsel in order to engage

in submissions with the Minister or to engage in the statutory judicial

review. In fact, it's our understanding that this omission results in a

constitutional violation. There's a section 7 breach tied in with a

section 10 breach, in that these entities are not given an opportunity

to hire and retain counsel in order to defend themselves. That

constitutional frailty could be a significant problem for this

legislation in the future."

Academics

Dr. Christina Szurlej, Endowed Chair, Atlantic

Human

Rights

Centre, St. Thomas University:

"Though Bill C-59 has addressed some shortcomings found

in the Anti-Terrorism Act, 2015,

concerns

remain

regarding

its

impact

on

human

rights,

particularly

the

rights

to

privacy, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of

expression, liberty and security, democratic rights, due process

rights, and anti-discrimination protections."

"If we're talking about invading the privacy of an

individual, normally a warrant is required in order to do that. Yes,

there might be exceptional circumstances in certain cases, but the Charter of Rights and Freedoms is

in place for a reason -- to constitutionally protect those rights --

and any infringement must be reasonable. Simply saying that the

collection of data relates to the functions of CSIS doesn't meet that

threshold. Perhaps clearly demonstrating that there is an actual threat

to national security may cross that threshold."

Szurlej recommends: "Ensure any limitation of human

rights conforms with Canada's national and international obligations.

Any encroachment on human rights must be necessary, proportionate,

reasonable, and justifiable in a free and democratic society. The

government must ensure any collection of personal data is directly

linked to protecting public safety and national security, rather than

being tangentially connected to the duties and functions of CSIS or any

other agency. Legislation should be introduced to protect the Canadian

populace from third party commodification of personal data through

payment or subscription. The National Security and Intelligence Review

Agency should be provided with the authority to render binding

decisions. The role of the intelligence commissioner should be elevated

from part-time to full-time status."

Craig Forcese, Professor, University of Ottawa,

Faculty of Law, as an Individual:

"The new system will only resolve the constitutional

problem if it steers all [CSE] collection activities implicating

constitutionally protected information into the new authorization

process. The problem is this. Bill C-59's present drafting only

triggers this authorization process where an act of Parliament would

otherwise be contravened. This is a constitutionally under-inclusive

trigger. Some collection of information in which a Canadian has a

constitutional interest does not violate an act of Parliament, for

example, some sorts of metadata. The solution is simple. Expand the

trigger to read as follows: 'Activities carried out by the

Establishment in furtherance of the foreign intelligence' or

cybersecurity 'aspect of its mandate must not contravene any

other act of Parliament or involve the acquisition of information in

which a Canadian or person in Canada has a reasonable expectation of

privacy,'

unless they are authorized under one of these ministerial

authorizations that are subject to vetting by the intelligence

commissioner."

Wesley Wark, Professor,

Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, University of

Ottawa, as an Individual:

Wark speaks favourably of Bill C-59 throughout. One

comment he makes should dispel any notion that what the Liberals have

done is merely amend Bill C-51 to get rid of elements Canadians so

vehemently objected to:

"Bill C-59 represents a very ambitious and sweeping

effort to modernize the Canadian national security framework. It should

not be seen as just a form of tinkering with the previous government's

Bill C-51."

Minister, Intelligence, Police and Spy Agencies Address

Committee

On November 30 the Standing Committee on Public Safety

held its first hearing as part of its study of Bill C-59, An act

respecting national security matters. The hearing opened with

remarks from the Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale and then

questions from Committee members to be answered by Goodale and

officials from the Department of Public Safety and Emergency

Preparedness, Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Royal

Canadian Mounted Police, Communications Security Establishment (CSE)

and the Department of Justice.

To date, as a result of

avoiding a debate in the House

of

Commons on the bill, the government has not set out its arguments for

why the

powers in the legislation are required other than to say that it

is all about modernization and protecting Canadians. This

continued in the Committee. Goodale did not present the

government's rationale for the legislation nor explain the

various portions of the legislation and why they are being put

forward. He started with a brief introduction that everything they do

is to protect Canadians and to defend our rights and freedoms: To date, as a result of

avoiding a debate in the House

of

Commons on the bill, the government has not set out its arguments for

why the

powers in the legislation are required other than to say that it

is all about modernization and protecting Canadians. This

continued in the Committee. Goodale did not present the

government's rationale for the legislation nor explain the

various portions of the legislation and why they are being put

forward. He started with a brief introduction that everything they do

is to protect Canadians and to defend our rights and freedoms:

"Everything that our government does in terms of

national

security has two inseparable objectives: to protect Canadians and

to defend our rights and freedoms."

Neither he in his remarks nor any other MP on the

Committee even mentioned the hundreds of thousands of Canadians who

spoke out against Bill C-51 and demanded its complete repeal.

Instead Goodale sought to hide this from examination by presenting the

government's actions as coming from Canadians. "Bill C-59 is

the product of the most inclusive and extensive consultations

Canada has ever undertaken on the subject of national security.

We received more than 75,000 submissions from a variety of

stakeholders and experts as well as the general public, and of

course this committee also made a very significant contribution,

which I hope members will see reflected in the content of Bill

C-59."

"All of that input guided our work and led to the

legislation

that's before us today," he said.

This attempt to overcome the legitimacy crisis the

government

faces with its refusal to repeal Bill C-51 continued in the questions

and answers. The first question for the Minister was presented by

Toronto--Danforth, Liberal MP Julie Dabrusin who said: "As part of

the consultations that took place, I held a meeting in my riding

to which many people came. It was well attended. What came

through were some very strong concerns about ensuring privacy

rights and Charter rights. [...] Many people have come and asked

me why do we not simply repeal the former Bill C-51 from the

prior government, the prior Parliament. Why is any new

legislation required? Why not just repeal it and leave it as it

is?"

Goodale responded stating "Bill C-51 as a single piece

of

legislation no longer exists. It is now embedded in other pieces

of law and legislation that affect four or five different

statutes and a number of different agencies and operations of the

Government of Canada. It's now a little bit like trying to

unscramble eggs rather than simply repealing what was there

before."

He added, "Based on the consultation that you referred

to,

we

meticulously went through the security laws of Canada, whether

they were in Bill C-51 or not, and asked ourselves this key

question. Is this the best provision, the right provision, in the

public interest of Canadians to achieve two objectives -- to keep

Canadians safe and safeguard their rights and freedoms -- and to

accomplish those two objectives simultaneously?

"We honoured our election commitment of dealing with

five or

six specific things in Bill C-51 that we found particularly

problematic. Each one of those has been dealt with, as per our

promise, but in this legislation we covered a lot of other ground

that came forward not during the election campaign but as a part

of our consultation."

Making Dirty Tricks Charter-Proof

In his remarks Goodale focussed on addressing CSIS

"threat

reduction powers" which permit CSIS agents to do all sorts of

dirty tricks. He created the impression that Canadians'

main concern was with oversight of these powers rather than the

powers themselves. In response to concerns he said that "CSIS

needs clear authorities, and Canadians need CSIS to have clear

authorities without ambiguity so that they can do their job of

keeping us safe. This legislation provides that clarity. Greater

clarity benefits CSIS officers, because it enables them to go

about their difficult work with the full confidence that they are

operating within the parameters of the law and the

Constitution."

This "bill will ensure that

any measure CSIS takes is

consistent with the Charter of

Rights and Freedoms. Bill C-51

implied the contrary, but CSIS has been very clear that they have

not used that particular option in Bill C-51, and Bill C-59 will

end any ambiguity," he said. This "bill will ensure that

any measure CSIS takes is

consistent with the Charter of

Rights and Freedoms. Bill C-51

implied the contrary, but CSIS has been very clear that they have

not used that particular option in Bill C-51, and Bill C-59 will

end any ambiguity," he said.

In response to questions during the hearing concerning

Bill

C-51 and what Goodale asserts were the main problems he said, "The

most prominent issue that emerged from Bill C-51 was the original

wording of what became section 12.1 of the CSIS Act, which

implied, by the way the section was structured, that CSIS could

go to a court and get the authority of the court to violate the

Charter. Every legal scholar I've ever heard opine on this topic

has said that is a legal nullity. An ordinary piece of

legislation such as the CSIS Act

cannot override the Charter. The Charter is paramount. However, the

language in the way section

12.1 was structured left the impression that you could go to the

court and get authority to violate the Charter.

"In the language change that we have put into Bill

C-59,

first of all, we have specified a list of disruption activities

that CSIS may undertake with the proper court authorization, but

when they go to the court to ask for authority, the ruling

they're asking for from the court is not that it violate the Charter,

but that it fits within the Charter, that in fact it is

consistent with the Canadian Charter

of Rights and Freedoms,

including clause 1 of the Charter.

"That's the difference between the structure of the old

section and how we've tried to make it clear that the Charter

prevails."

Clause 1 of the Charter states: "1. The Canadian Charter of

Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out

in

it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as

can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic

society."

Elsewhere the Director of CSIS has explained in

relation to

these

"threat reduction powers" and the Charter that "if ever we were

to contemplate a threat reduction measure that would limit the

freedom of someone protected by the Charter, we would have to go

to the Federal Court to apply for such an authorization. The

Federal Court would then determine if the limit on that freedom

is reasonable and proportionate, which the Charter itself allows

for. That is how the proposed Bill C-59 addresses the Charter

issue for the threat reduction mandate."

Elsewhere in his remarks Goodale said, "Through the

collection of new provisions that are here in Bill C-59 we will

give CSIS and the RCMP and our other agencies the ability and the

tools to be as well informed as humanly possible about these

activities and to be able to function with clarity within the law

and within the Constitution."

David Vigneault from CSIS also explained that Bill C-59

does

not change any of the threat reduction measures CSIS can take for

which they do not require a warrant. He gave the example that "if

we were aware of an individual who wanted to travel abroad for

the purpose of joining a terrorist organization, we would not

need a warrant to intervene with a parent or with people in close

proximity to this individual to inform them of what we know in

order for them maybe to have an influence on that. Bill C-59 does

not make any changes to that provision."

Definitions of Terrorism Offences

Goodale turned to the

definition of "terrorist propaganda" in the new legislation and

the existing criminal offence of promoting terrorism

which was included in Bill C-51. In explaining the new wording

which would outlaw "counselling the commission of a terrorism

offence," Goodale stated, "The problem with the way the law is

written at the moment, as per Bill C-51 is that it is so broad

and so vague that it is virtually unusable, and it hasn't been

used. Bill C-59 proposes terminology that is clear and familiar

in Canadian law. It would prohibit counselling another person to

commit a terrorism offence. This does not require that a

particular person be counselled to commit a particular offence.

Simply encouraging others to engage in non-specific acts of

terrorism will qualify and will trigger that section of the Criminal Code." Goodale turned to the

definition of "terrorist propaganda" in the new legislation and

the existing criminal offence of promoting terrorism

which was included in Bill C-51. In explaining the new wording

which would outlaw "counselling the commission of a terrorism

offence," Goodale stated, "The problem with the way the law is

written at the moment, as per Bill C-51 is that it is so broad

and so vague that it is virtually unusable, and it hasn't been

used. Bill C-59 proposes terminology that is clear and familiar

in Canadian law. It would prohibit counselling another person to

commit a terrorism offence. This does not require that a

particular person be counselled to commit a particular offence.

Simply encouraging others to engage in non-specific acts of

terrorism will qualify and will trigger that section of the Criminal Code."

"Because the law will be more clearly drafted, it will

be

easier to enforce. Perhaps we will actually see a prosecution

under this new provision. There has been no prosecution of this

particular offence as currently drafted," he added.

In response to concerns Goodale cited that were raised

in the

Parliament about new "accountability" measures and whether they

would provide "too many hoops" for security and intelligence

agencies to jump through, he said this is not the case and that

two of the country's leading national security experts, Craig

Forcese and Kent Roach, said the bill represents "solid

gains -- measured both from a rule of law and civil liberties

perspective -- and come at no credible cost to security."

Turning to the issue of oversight and review he said,

"Some of

the scrutiny that we are providing for in the new law will be

after the fact, and where there is oversight in real time we've

included provisions to deal with exigent circumstances when

expedience and speed are necessary."

He added that "accountability is, of course, about

ensuring

that the

rights and freedoms of Canadians are protected, but it is also

about ensuring that our agencies are operating as effectively as

they possibly can to keep Canadians safe. Both of these vital

goals must be achieved simultaneously -- safety and rights together,

not one or the other."

Criminalization of Dissent

Conservative MP Dave MacKenzie asked the Minister to

explain

Bill C-59 "expressly prohibiting protest and advocacy and so on,

will the changes in the new bill result in charges that were not

allowed for in Bill C-51? Have we enhanced the probabilities of

prosecution in Bill C-59 over Bill C-51?"

Goodale said "the problem with the

language in Bill

C-51 was

that it was very broad, and in the language of lawyers in court,

it was so broad that it was vague and unenforceable. If you

recall, there was some discussion during the election campaign in

2015 that the language in that particular section might have been

used to capture certain election campaign ads, which obviously

wasn't the intention of the legislation. Goodale said "the problem with the

language in Bill

C-51 was

that it was very broad, and in the language of lawyers in court,

it was so broad that it was vague and unenforceable. If you

recall, there was some discussion during the election campaign in

2015 that the language in that particular section might have been

used to capture certain election campaign ads, which obviously

wasn't the intention of the legislation.

"We've made it more precise without affecting its

efficacy,

and I think we made it more likely that charges can be laid and

successfully prosecuted, because we have paralleled an existing

legal structure that courts, lawyers, and prosecutors are

familiar with, and that is the offence of counselling. Clearly,

it doesn't have to be a specific individual counselling another

specific individual to do a specific thing. If they are generally

advising people to go out and commit terror, that's an offence of

counselling under the act the way we've written it."

Pre-Emptive Arrest Powers

Douglas Breithaupt, Director and General Counsel of the

Criminal Law Policy Section, Department of Justice, addressed a

question from Conservative MP Glen Motz about how the change of

terminology in section 83.3 of the Criminal

Code, from "is likely

to prevent" a terrorist activity to "is necessary to prevent" a

terrorist activity would impact or affect "our ability to make

preventative arrests?" Breithaupt explained that Bill C-59 would

propose to revert one of the thresholds to what it was before

former Bill C-51. "There are two thresholds: that the peace

officer have, first, reasonable grounds to believe that a

terrorist activity may be carried out, and second, reasonable

grounds to suspect that the imposition of a recognizance with

conditions or the arrest of the person is, as it currently reads,

'likely to prevent the carrying out of the terrorist

activity'."

Sharing Versus Disclosure

NDP MP Mathew Dubé asked the Minister to clarify

the

difference between "sharing" and "disclosure," as disclosure is

replacing sharing in the Security of

Canada Information Sharing

Act. The Minister's response was that "no new power of

collection

is being created here. This is all in reference to information

that already exists." Elsewhere during the hearing Vincent Rigby,

Associate Deputy Minister Department of Public Safety and

Emergency Preparedness, explained that "it's actually quite

important. As the Minister suggested, moving from 'sharing' to

'disclosing' is also making it clear that this is not about

collection. This is about disclosing information, and sometimes I

think within the definition of 'sharing,' it can be implicit that

there's a collection dimension as well, so we wanted absolute

clarity in that regard.

"Also, disclosing makes it very clear that it's from

one

body, one organization, to another organization, so there are

certain requirements on the disclosing organization or agency now

in terms of the information they give to another agency or

organization."

Cyber Operations

CSE Chief Bossenmaier was asked by Conservative MP

Cheryl

Gallant to explain provisions in the proposed legislation

establishing the CSE which include the Minister of Foreign

Affairs in decision-making when authorizing cyber operations.

She responded explaining that for defensive

cyber-operations

the Minister would need to be consulted, while in "active" (in

fact offensive operations) the Minister's approval along with

that of the Minister of Defence would be required. She stated

that "the Minister of Foreign Affairs would have an interest in

and responsibility for Canada's international and foreign

affairs, as these activities would be implicating foreign targets

or threats to Canada, which would be part of the rationale for

that."

Powers for Collection of Information by CSE and CSIS

NDP MP Matthew Dubé also raised a question about

a

contradiction

in the powers given to the CSE in relation to collecting

publicly available information, citing subsection 23(1): "we see

that it specifically mentions that the activities done by the

centre 'must not be directed at a Canadian or any person in

Canada', while proposed section 24 says, 'Despite subsections

23(1) and (2), the Establishment may carry out [...]." He added,

"Essentially, we're saying that normally it wouldn't be against

Canadians or any person in Canada, but now that's no longer the

case, because it's specifically saying that it's 'despite'

proposed section 23." Dubé noted that "acquiring, using,

analyzing, retaining or disclosing

infrastructure information for the purpose of research and

development, for the purpose of testing systems or conducting

cyber security and information assurance activities on the

infrastructure from which the information was acquired. To me,

that seems to create a situation whereby you could be collecting

information from infrastructure here in Canada, which obviously

Canadians are using, without necessarily the same accountability

that's created by omitting Canadians in proposed section 23."

Greta Bossenmaier, Chief of

the Communications Security

Establishment said "we focus on foreign targets and foreign

threats to Canada, so we don't have a mandate to focus on

Canadians. We're definitely an organization that's focused on

foreign threats to Canada." She added later "refer to proposed

subsection 24(1). In the actual first text there, it talks about 'the

following activities in furtherance of its mandate'. Again,

our mandate is foreign signals intelligence and cyber security

protection. That really is the overarching piece that would be

associated with the rest of the subsections." She closed by

stating "anything that would happen under proposed subsection

24(1), would be addressed and covered under the review mechanisms

that the Minister already spoke about in terms of the national

security and intelligence review agency, and of course, the new

National Security and Intelligence Committee of

Parliamentarians." Greta Bossenmaier, Chief of

the Communications Security

Establishment said "we focus on foreign targets and foreign

threats to Canada, so we don't have a mandate to focus on

Canadians. We're definitely an organization that's focused on

foreign threats to Canada." She added later "refer to proposed

subsection 24(1). In the actual first text there, it talks about 'the

following activities in furtherance of its mandate'. Again,

our mandate is foreign signals intelligence and cyber security

protection. That really is the overarching piece that would be

associated with the rest of the subsections." She closed by

stating "anything that would happen under proposed subsection

24(1), would be addressed and covered under the review mechanisms

that the Minister already spoke about in terms of the national

security and intelligence review agency, and of course, the new

National Security and Intelligence Committee of

Parliamentarians."

Bossenmaier also explained that with the new powers the

CSE

would be in a position not only to respond to attacks on

government and non-government infrastructure, but also to "go out

and try to prevent an attack against Canada or Canadians or

Canadian infrastructure before it happened."

Liberal MP Michel Picard asked the Minister about how

Bill C-59

overcomes the obstacles to keeping and using information

collected as a result of a ruling by Supreme Court Justice Simon

Noël,

which "found problems with the types of information that can be

investigated and kept, and with the extent to which it is

possible to investigate."[1]

Goodale explained that Bill C-59 "captures Justice

Noël's

advice and judgment for a procedure going forward dealing with

the management of data and datasets."

CSIS Director David Vigneault explained that under the

new

powers "Bill C-59 sets out categories of information that are

determined by the Minister. He tells me, as director, which

categories of information we have the right to use. The men and

women of the service will go and gather that information in an

organized fashion. If the information is part of a Canadian

dataset, the Intelligence Commissioner will have to assess the

Minister's decision.

"With Canadian information, the Federal Court will have

to

determine whether we can use it and keep it. The way in which we

use that information will be reviewed by the new National

Security and Intelligence Review Agency and the National Security

and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians.

"The way in which the categories are determined by the

Minister, the way in which we will use Canadian information, the

role that the Federal Court and the Intelligence Commissioner

will play, and the fact that any subsequent use of the

information will be reviewed by oversight committees, all this

will allow us to use information that is absolutely essential in

confronting 21st century threats."

Later Vigneault was asked by Dubé about

"unselected

datasets." "[I]n the bill it says that the Minister and the new

commissioner are going to determine whether or not it is

appropriate to gather and keep that data.

"How do you go about distinguishing between the

datasets? For

example, the Minister or the commissioner could decide that one

dataset is appropriate, because it relates to someone who poses

no threat but who may have had a conversation with a suspect you

are targeting. How do you distinguish that dataset from the other

information about legitimate associates of the person who may be

a threat too?

"Put in a better way, how do you go about

distinguishing

between the other data and the unselected datasets that affect

people who have nothing to do with the suspect?"

Vigneault explained that "a quasi-judicial review is

conducted by the Intelligence Commissioner. If the information

affects Canadians, the Federal Court will decide whether it is

absolutely necessary for CSIS to keep and use the information.

The Federal Court will apply the privacy test to determine

whether to let us use the information. The system to be put in

place by Bill C-59 includes criteria that allow us to use the

information."

Then he added CSIS' view that it requires large amounts

of

information about Canadians' relations to one another to rule out

if Canadians are "a threat." He said, "Having a bigger dataset allows

us

to characterize threats and to say with whom such and such an

individual is in contact, and whether or not that constitutes a

threat. Often, it allows us to establish that there is no threat.

Having that dataset means that CSIS does not investigate innocent

people."

Dubé responded asking "If the court determines

that you have

the right to collect that information because the target is

legitimate, how do you go about distinguishing the legitimate

target from the unselected data that will inevitably be

collected? Has a system been put in place?"

Vigneault responded without addressing the question

that "the

unselected data will be separated out," and that "only the

designated people will be able to have access to that information

[...] Unselected data will be segregated. Designated people will

be able to make requests to use it. Each time that is done, the

activities will be reviewed to make sure that our procedures and

our implementation comply with the spirit of the law." Asked

again how they would separate the data Vigneault explained.

"We do not start our investigations from selected data.

We

start them from factors that are related to threats."

If an identified target is implicated in potential

terrorism

or espionage, and if we see that that person is in contact with

someone -- certain information can be useful to us, like a telephone

number -- we can then check in the unselected data we have been

authorized to keep. That is part of the process I explained to

you earlier."

"What people are afraid of is that we will be going on

fishing expeditions."

"There's no fishing expedition," he asserted.

Changes to Youth

Criminal Justice Act

Liberal MP Julie Dabrusin asked "We're now creating a

system

whereby information about young offenders will be available to

people issuing passports. Is that consistent with the objectives

of the Youth Criminal Justice Act?"

Douglas Breithaupt of the Department of Justice simply

did

not answer whether it was consistent with the objectives of the Youth Criminal Justice Act

or why the change was being made but

rather said that it was consistent with the Security of Canada

Information Sharing Act. He indicated how

the provision could be used, "For example, the fact that a

youth has been subject to a terrorism peace bond could be made

available for consideration in making those decisions."

Liberal MP Sven Spengemann asked "about Canadian youth

and

their vulnerability to terrorism."

He asked the Minister to elaborate on Clause 159 of the

bill

which he said "brings the Youth

Criminal Justice Act into

connection with Bill C-59, applies it to Bill C-59, including the

principle that detention is not a substitute for social measures

and also that preventative detention, as provided for in section

83.3 of the Criminal Code,

falls into that same framework. It's

not a substitute."

He added, "I wonder if you could comment on your vision

of

how

the bill relates to young offenders, vulnerable youth,

essentially the pre-commission of any terrorist offences or

recruitment by networks, and then also your broader vision about

how we can do better in terms of preventing terrorism in the

first place by making sure these networks do not prey on Canadian

youth and children."

Spengemann did not explain what he meant by

pre-commission of any terrorist acts.

The Minister said that with the new legislation "the Youth

Criminal Justice Act applies, so that is the process by which

young offenders will be managed under this law."

Turning to "prevention" he cited the government's

creation of

the new Canada Centre for Community Engagement and Prevention of

Violence, "so we would have a national office that could

coordinate the activities that are going along at the local and

municipal and academic levels across the country, put some more

resources behind those, and make sure we are sharing the very

best ideas and information so that if we can prevent a tragedy,

we actually have the tools to do it."

Changes to No-Fly List

Spengemann also asked the Minister to explain how the

amendments to the Secure Air Travel

Act provide redress for

people, particularly children, who are prevented from travelling

as a result of having the same or similar name to someone on the

No-Fly List.

Vincent Rigby, Associate Deputy Minister, Department of

Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, responded, that "it's

starting off with a centralized screening system so that

the government actually does the screening. Right now that is the

responsibility of the airline. We'll bring it back to the

government so that we can actually provide more rigorous and

consistent screening across the board. In the legislation itself

there are also references to the notion of an identification

number that will allow, those who request the identification

number to be screened ahead of time. If there's any

misunderstanding with respect to being on the list, that can be

addressed before they actually show up at the airport [...] in

cases where a child, for example, is not on the list, the

government will inform the parents of that. We feel that is an

important provision in that there's a great deal of apprehension

when there is a false positive match from parents who ask if

their child is on the list. Whether it's through accident or

through some other provision, I think it removes a lot of that

apprehension if we can actually say to a parent that the child is

not on the list."

"By having the centralized screening process, we are

actually

going to have to build the system up from the ground. It will

require a big information technology fix that will require

significant funding over time to make that happen."

Spengemann then asked the officials to explain, with

respect to people being prevented

from air travel as a result of a No-Fly List, why "are

we in

the current situation?"

Monik Beauregard, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister,

National

and Cyber Security Branch of the Department of Public Safety and

Emergency Preparedness merely responded: "I can't really

say why we're in the current situation. We are working with the

U.S. We have established a Canada-U.S. redress working group to

also facilitate the troubles that some air passengers may

experience. We are looking to the American experience in

establishing their redress program and learning lessons from the

way they have done it."

Liberal MP Pam Damoff explained that a young man in her

riding has his name shared on the list. She asked "who creates

and who maintains the list? Is it the airlines or the

government?"

Beauregard stated, "The government creates the Secure

Air

Travel

Act [SATA] list based on a dual threshold of identifying

individuals who are suspected of posing a threat to airlines but

also individuals who are suspected of travelling abroad to

participate in terrorist activities. That is not to say that

airlines don't have their own lists, but they're not

terrorism-related. Airlines will have their own list based on

people who've had rage fits on airlines and things like that.

There's quite a complex process in place when somebody is flagged

at registration. They may be on the SATA list. There's a whole

process going back to the government, to Transport Canada, and to

Public Safety to vet whether or not that person is a close name

match or an actual person on the list."

Damoff asked specifically, "We're not using a U.S. list

then,

in Canada? That's a question that I'm often asked," to which

Beauregard responded, "No. Again, as I explained, we have our own

list. The list that is shared with airlines is the Canadian

list." Damoff followed up, "There seems to be

confusion, certainly among the parents, that there is this list

somewhere that every country has access to." Beauregard did not

respond to clarify this. [2]

Note

1. In that case Justice

Noël ruled that CSIS kept

electronic metadata about "non-threat" Canadians and "third

parties" over a 10-year period illegally and used the data at its

Operational Data Analysis Centre without informing the Minister

of Public Safety at the time. According to court documents,

CSIS created the Operational Data Analysis Centre (ODAC) in 2006

to be a "centre of excellence for the exploitation and analysis"

of different data sets. CSIS should not have retained the

information since it was not directly related to threats to the

security of Canada, the ruling said. The data about data "allowed

the agency to draw out "specific, intimate insights into the

lifestyle and personal choices of individuals,"

The head of CSIS at the time Michel Coulombe responded,

"All associated data collected under warrants was done

legally." He said, "The court's key concerns relates to our

retention of non-threat-related associated data linked with

third-party communication after it was collected."

"CSIS, in consultation with the Department of Justice,

interpreted the CSIS Act to

allow for the retention of this

subset of associated data. It is now clear that the Federal Court

disagrees with this interpretation."

In his ruling Justice Noël suggested it may be

time to revisit

the CSIS Act of 1984,

which is "showing its age" in a technologically

advanced world.

"Canada can only gain from weighing such important

issues

once again," Noël wrote. "Canadian intelligence agencies should

be provided the proper tools for their operations but the public

must be knowledgeable of some of their ways of operating."

In a statement issued following the ruling Goodale

welcomed

the ruling, saying the federal government would not be appealing

the decision. "I also take very seriously the explicit finding by

Justice Noël that CSIS had failed in its duty to be candid with

the court," Goodale said in the statement. "In matters of

security and intelligence, Canadians need to have confidence that

all the departments and agencies of the government of Canada are

being effective at keeping Canadians safe, and equally, that they

are safeguarding our rights and freedoms."

2. The Secure Air

Travel Act permits the Minister to

establish who is on the no-fly list, which in effect means that if the

U.S. or another government requests that their list be included

in Canada's, the Minister can do this. Thus the assertion that a

list is "Canadian" hides that the Minister has the arbitrary

authority to place anyone on the list based on their "reasonable

grounds to suspect a person will:

(a) engage or attempt to

engage in an act that would

threaten transportation security; or

(b) travel by air for the

purpose of committing an act

or

omission that

(i) is an offence under

section 83.18, 83.19 or 83.2

of the Criminal Code or

an offence referred to in paragraph (c) of the

definition terrorism offence in section 2 of that Act, or

(ii) if it were committed in

Canada, would constitute

an

offence referred to in subparagraph (I).

No proof is required. Furthermore the Act states that

the

government can share the list with a foreign state and enter into

agreements concerning the list, meaning that through regulation

Canada's list can be linked to the U.S. list or the lists of other

countries or

bodies and changed based on changes to those lists.

For Your Information

What the Bill Contains

Provisions:

Preamble

Bill C-59

begins with a Preamble, which in essence states that the

government needs new powers for police and spy agencies to keep

up with "changing threats" in order to "keep Canadians safe" and

protect Canada's national security. Furthermore, these powers

must be wielded in accordance with the rule of law, which is made

synonymous with respecting the

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It

repeats the notion that the issue is for government to

balance rights with security, as if they are separate, and that

this must be done in a manner to "ensure public trust and

confidence" in the police and spy agencies, which the Preamble

says can be done with enhanced "accountability and

transparency."

The Preamble ends stating:

"Whereas many Canadians expressed concerns about

provisions

of the Anti-Terrorism Act, 2015; [Bill C-51 which the Harper government and

the Liberals together

passed -- TML ed. note]

"And whereas the Government of Canada engaged in

comprehensive public consultations to obtain the views of

Canadians on how to enhance Canada's national security framework

and committed to introducing legislation to reflect the views and

concerns expressed by Canadians..."

Part 1: New National Security and Intelligence Review

Act

Part 1 enacts the National Security and

Intelligence

Review Agency Act, which establishes the National Security

and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) and sets out its

composition, mandate and powers. This would eliminate the

Security Intelligence Review Committee and transfer some of its

powers and mandate to this Agency. The mandate of the Agency is

to "review all national security and intelligence activities

across Government."

The Bill folds the review and complaint functions of

the

Security Intelligence Review Committee of CSIS and the Office of

the Communications Security Establishment Commissioner into the

new Agency. The review and complaints functions of the Civilian

Review and Complaints Commission of the RCMP would be moved to

the new agency.

The Agency would "collaborate" with the National

Security and

Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians which the Trudeau government

has