|

March 17, 2018 - No. 10

Supplement

135th

Anniversary of the

Death of Karl Marx

Revolutionaries

Take Up Marxism

As a

Guide to Action

PDF

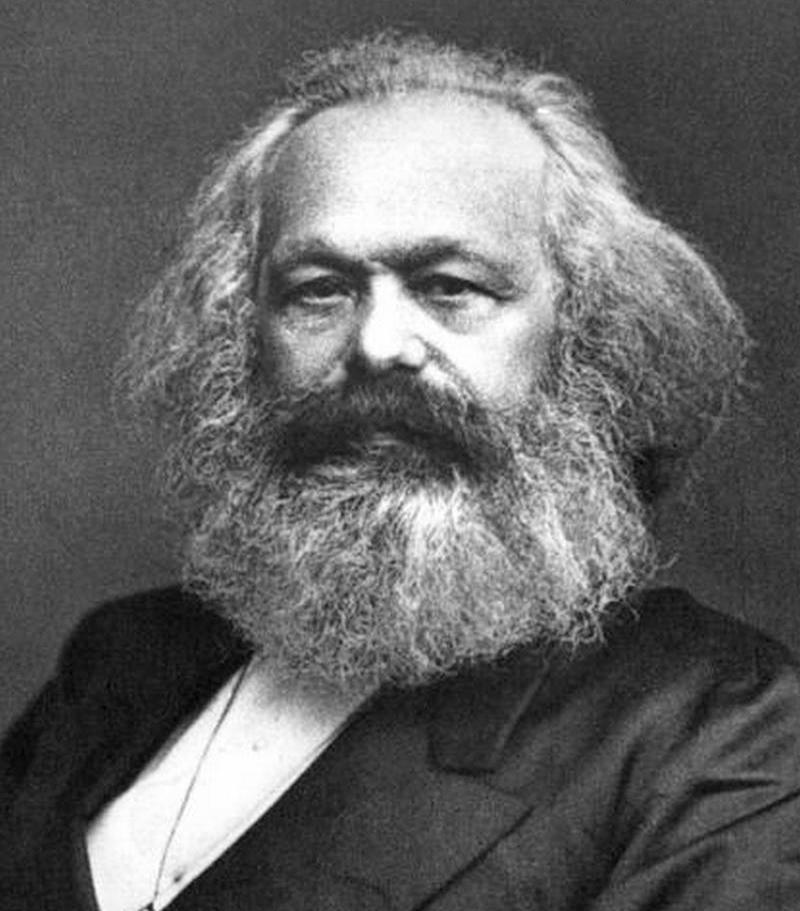

Karl Marx addressing the founding meeting of the International

Workingmen's Association in London, September 28, 1864.

• Speech at

the Graveside of Karl Marx

- Frederick Engels, Highgate Cemetery, London, March

17, 1883 -

• The Three Sources and Three

Component Parts of Marxism

- V.I. Lenin -

135th Anniversary of the Death of Karl

Marx

Revolutionaries Take Up Marxism

As a Guide to Action

Mankind is shorter by a

head, and that the

greatest head of our time. The movement of the proletariat goes

on, but gone is the central point to which Frenchmen, Russians,

Americans and Germans spontaneously turned at decisive moments to

receive always that clear indisputable counsel which only genius

and consummate knowledge of the situation could give. Local

lights and small talents, if not the humbugs, obtain a free hand.

The final victory remains certain, but the detours, the temporary

and local deviations -- unavoidable as is -- will grow more than

ever. Well, we must see it through; what else are we here for?

And we are far from losing courage because of it. -- Frederick

Engels, March 15, 1883 [1]

Many changes have taken place

since the life-long friend and

close collaborator of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, wrote those

words on March 15, 1883, one day after Marx passed away. And

despite all the twists and turns the working class has gone

through since then in its struggle for empowerment, the life and

work of Karl Marx remain a "central point" to which all communist

revolutionaries and all those who aspire for a new society must

turn. Today, as was the case 135 years ago, only Marxism can

provide the kind of "clear indispensable counsel which only

genius and consummate knowledge of the situation could give."

Turning to Marxism means paying attention to the concrete

analysis of the concrete conditions, to ensure that the "central

point" of the contemporary world is established around which

everybody else can rally and unite. Many changes have taken place

since the life-long friend and

close collaborator of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, wrote those

words on March 15, 1883, one day after Marx passed away. And

despite all the twists and turns the working class has gone

through since then in its struggle for empowerment, the life and

work of Karl Marx remain a "central point" to which all communist

revolutionaries and all those who aspire for a new society must

turn. Today, as was the case 135 years ago, only Marxism can

provide the kind of "clear indispensable counsel which only

genius and consummate knowledge of the situation could give."

Turning to Marxism means paying attention to the concrete

analysis of the concrete conditions, to ensure that the "central

point" of the contemporary world is established around which

everybody else can rally and unite.

Today, even though there is one International Communist

and

Workers' Movement, there is no one central point as existed at

the time of the First International established by Karl Marx and

Frederick Engels on September 28, 1864, at which time the

authority of Marxism was established, or later at the time of the

Third International, established by V.I. Lenin on March 2, 1919,

when the authority of Leninism prevailed. The lack of one central

point today is consistent with the state of affairs which

prevails as a result of the retreat of revolution where communist

parties the world over have their own central points. While this

reflects the existence of different tendencies within this

movement, it also underscores the need to elaborate Contemporary

Marxist-Leninist Thought as the central point which develops and

becomes profound only in the course of practice.

Painting of Karl Marx in discussion with workers.

In this regard, the greatest achievement of Karl Marx

was to

be a revolutionist who could not carry on his activities without

revolutionizing social science. Social science was a body of

knowledge scattered into various sections and claimed as the

property of this or that individual or sect. With his two

discoveries of the general law of motion of nature and society,

the theory of dialectical and historical materialism, and the

specific law of motion of capitalist society, the theory of

surplus value, Karl Marx revolutionized social science as the

body of knowledge of all those in whose interest it will be to

organize proletarian socialist revolution. Revolutionized social

science could no longer be merely the domain of some philosophers

or ivory tower intellectuals. It became the preserve of those who

would revolutionize society.

These achievements of Karl Marx, who remained a

revolutionist

in all fields, served as a guide to action for V.I. Lenin who

further revolutionized social science, confirming what Marx had

predicted, that without revolutionary theory there can be no

revolutionary movement. This issue which posed itself at the time

Karl Marx carried out his work, and after him V.I. Lenin,

continues to pose itself today. All those who wish to be

revolutionists have to follow Marxism as a guide in their

practice.

On the occasion of the 135th anniversary of the death

of Karl

Marx, TML Weekly repeats what Engels wrote on March 15,

1883: "The final victory remains certain, but the detours, the

temporary and local deviations -- unavoidable as is -- will grow

more than ever. Well, we must see it through; what else are we

here for? And we are far from losing courage because of it."

Note

1. Marx and Engels, Selected

Correspondence, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1965, p.

361.

Speech at the Graveside of Karl Marx

- Frederick Engels, Highgate Cemetery,

London,

March 17, 1883 -

On the 14th of March, at a

quarter to three in the

afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had

been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back

we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep -- but forever. On the 14th of March, at a

quarter to three in the

afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had

been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back

we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep -- but forever.

An immeasurable loss has been sustained both by the

militant

proletariat of Europe and America, and by historical science, in

the death of this man. The gap that has been left by the

departure of this mighty spirit will soon enough make itself

felt.

Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of

organic

nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human

history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of

ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter

and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art,

religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate

material means of subsistence and consequently the degree of

economic development attained by a given people or during a given

epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the

legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the

people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which

they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had

hitherto been the case.

But that is not all. Marx also discovered the special

law of

motion governing the present-day capitalist mode of production

and the bourgeois society that this mode of production has

created. The discovery of surplus value suddenly threw light on

the problem, in trying to solve which all previous

investigations, of both bourgeois economists and socialist

critics, had been groping in the dark.

Two such discoveries would be enough for one lifetime.

Happy

the man to whom it is granted to make even one such discovery.

But in every single field which Marx investigated -- and he

investigated very many fields, none of them superficially -- in

every field, even in that of mathematics, he made independent

discoveries.

Such was the man of science.

But this was not even half

the

man. Science was for Marx a historically dynamic, revolutionary

force. However great the joy with which he welcomed a new

discovery in some theoretical science whose practical application

perhaps it was as yet quite impossible to envisage, he

experienced quite another kind of joy when the discovery involved

immediate revolutionary changes in industry, and in historical

development in general. For example, he followed closely the

development of the discoveries made in the field of electricity

and recently those of Marcel Deprez. Such was the man of science.

But this was not even half

the

man. Science was for Marx a historically dynamic, revolutionary

force. However great the joy with which he welcomed a new

discovery in some theoretical science whose practical application

perhaps it was as yet quite impossible to envisage, he

experienced quite another kind of joy when the discovery involved

immediate revolutionary changes in industry, and in historical

development in general. For example, he followed closely the

development of the discoveries made in the field of electricity

and recently those of Marcel Deprez.

For Marx was before all else a revolutionist. His real

mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the

overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions

which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation

of the modern proletariat, which he was the first to make

conscious of its own position and its needs, conscious of the

conditions of its emancipation. Fighting was his element. And he

fought with a passion, a tenacity and a success such as few could

rival. His work on the first Rheinische

Zeitung

(1842), the Paris

Vorwärts (1844), the Deutsche

Brüsseler

Zeitung (1847), the Neue

Rheinische Zeitung (1848-49), the New York Tribune (1852-61), and

in addition to these, a host of militant pamphlets, work in

organisations in Paris, Brussels and London, and finally,

crowning all, the formation of the great International Working

Men's Association -- this was indeed an achievement of which its

founder might well have been proud even if he had done nothing

else.

And, consequently, Marx was the best hated and most

calumniated man of his time. Governments, both absolutist and

republican, deported him from their territories. Bourgeois, both

conservative or ultra-democratic, vied with one another in

heaping slanders upon him. All this he brushed aside as though it

were a cobweb, ignoring it, answering only when extreme necessity

compelled him. And he died beloved, revered and mourned by

millions of revolutionary fellow workers -- from the mines of

Siberia to California, in all parts of Europe and America -- and

I make bold to say that though he may have had many opponents he

had hardly one personal enemy.

His name will endure through the ages, and so also will

his

work!

Unveiling of monument to Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery, London,

England in 1956.

The Three Sources and Three Component

Parts of Marxism

- V.I. Lenin -

Marx and Engels at Rheinische Zeitung

printing house in Cologne

(Painting by E. Chapiro)

Throughout the civilised world the teachings of Marx

evoke

the utmost hostility and hatred of all bourgeois science (both

official and liberal), which regards Marxism as a kind of

"pernicious sect." And no other attitude is to be expected, for

there can be no "impartial" social science in a society based on

class struggle. In one way or another, all official and

liberal science defends wage-slavery, whereas Marxism has

declared relentless war on that slavery. To expect science to be

impartial in a wage-slave society is as foolishly naïve as to

expect impartiality from manufacturers on the question of whether

workers' wages ought not to be increased by decreasing the

profits of capital.

But this is not all. The history of philosophy and the

history of social science show with perfect clarity that there is

nothing resembling "sectarianism" in Marxism, in the sense of its

being a hidebound, petrified doctrine, a doctrine which arose away

from the high road of the development of world

civilisation. On the contrary, the genius of Marx consists

precisely in his having furnished answers to questions already

raised by the foremost minds of mankind. His doctrine emerged as

the direct and immediate continuation of the teachings of

the greatest representatives of philosophy, political economy and

socialism.

The Marxist doctrine is omnipotent because it is true.

It is

comprehensive and harmonious, and provides men with an integral

world outlook irreconcilable with any form of superstition,

reaction, or defence of bourgeois oppression. It is the

legitimate successor to the best that man produced in the

nineteenth century, as represented by German philosophy, English

political economy and French socialism.

It is these three sources of Marxism, which are also

its

component parts that we shall outline in brief.

I

The philosophy of Marxism is materialism.

Throughout

the

modern

history

of

Europe,

and

especially

at

the

end of the eighteenth century in France, where a resolute

struggle was conducted against every kind of medieval rubbish,

against serfdom in institutions and ideas, materialism has proved

to be the only philosophy that is consistent, true to all the

teachings of natural science and hostile to superstition, cant

and so forth. The enemies of democracy have, therefore, always

exerted all their efforts to "refute," undermine and defame

materialism, and have advocated various forms of philosophical

idealism, which always, in one way or another, amounts to the

defence or support of religion.

Marx and Engels defended philosophical materialism in

the

most determined manner and repeatedly explained how profoundly

erroneous is every deviation from this basis. Their views are

most clearly and fully expounded in the works of Engels, Ludwig

Feuerbach and the End of Classical German

Philosophy and Anti-Dühring, which, like the Communist

Manifesto, are handbooks for every

class-conscious worker.

But Marx did not stop at eighteenth-century

materialism: he

developed philosophy to a higher level; he enriched it with the

achievements of German classical philosophy, especially of

Hegel's system, which in its turn had led to the materialism of

Feuerbach. The main achievement was dialectics, i.e., the

doctrine of development in its fullest, deepest and most

comprehensive form, the doctrine of the relativity of the human

knowledge that provides us with a reflection of eternally

developing matter. The latest discoveries of natural science --

radium, electrons, the transmutation of elements -- have been a

remarkable confirmation of Marx's dialectical materialism despite

the teachings of the bourgeois philosophers with their "new"

reversions to old and decadent idealism.

Marx deepened and developed philosophical materialism

to the

full, and extended the cognition of nature to include the

cognition of human society. His historical materialism

was a great achievement in scientific thinking. The chaos and

arbitrariness that had previously reigned in views on history and

politics were replaced by a strikingly integral and harmonious

scientific theory, which shows how, in consequence of the growth

of productive forces, out of one system of social life another

and higher system develops -- how capitalism, for instance, grows

out of feudalism.

Just as man's knowledge reflects nature (i.e.,

developing

matter), which exists independently of him, so man's social

knowledge (i.e., his various views and doctrines --

philosophical, religious, political and so forth) reflects the

economic system of society. Political institutions are a

superstructure on the economic foundation. We see, for example,

that the various political forms of the modern European states

serve to strengthen the domination of the bourgeoisie over the

proletariat.

Marx's philosophy is a consummate philosophical

materialism

that has provided mankind, and especially the working class, with

powerful instruments of knowledge.

II

Having recognised that the economic system is

the

foundation on which the political superstructure is erected, Marx

devoted his greatest attention to the study of this economic

system. Marx's principal work, Capital, is devoted to a

study of the economic system of modern, i.e., capitalist,

society.

Classical political economy, before Marx, evolved in

England,

the most developed of the capitalist countries. Adam Smith and

David Ricardo, by their investigations of the economic system,

laid the foundations of the labour theory of value. Marx

continued their work; he provided a proof of the theory and

developed it consistently. He showed that the value of every

commodity is determined by the quantity of socially necessary

labour time spent on its production.

Where the bourgeois economists saw a relation between

things

(the exchange of one commodity for another) Marx revealed a relation

between

people. The exchange of commodities

expresses the connection between individual producers through the

market. Money signifies that the connection is becoming

closer and closer, inseparably uniting the entire economic life

of the individual producers into one whole. Capital

signifies a further development of this connection: man's

labour-power becomes a commodity. The wage-worker sells his

labour-power to the owner of land, factories and instruments of

labour. The worker spends one part of the day covering the cost

of maintaining himself and his family (wages), while the other

part of the day he works without remuneration, creating for the

capitalist surplus-value, the source of profit, the

source of the wealth of the capitalist class.

The doctrine of surplus-value is the corner-stone of

Marx's

economic theory.

Capital, created by the labour of the worker, crushes

the

worker, ruining small proprietors and creating an army of

unemployed. In industry, the victory of large-scale production is

immediately apparent, but the same phenomenon is also to be

observed in agriculture, where the superiority of large-scale

capitalist agriculture is enhanced, the use of machinery

increases and the peasant economy, trapped by money-capital,

declines and falls into ruin under the burden of its backward

technique. The decline of small-scale production assumes

different forms in agriculture, but the decline itself is an

indisputable fact.

By destroying small-scale production, capital leads to

an

increase in productivity of labour and to the creation of a

monopoly position for the associations of big capitalists.

Production itself becomes more and more social -- hundreds of

thousands and millions of workers become bound together in a

regular economic organism -- but the product of this collective

labour is appropriated by a handful of capitalists. Anarchy of

production, crises, the furious chase after markets and the

insecurity of existence of the mass of the population are

intensified.

By increasing the dependence of the workers on capital,

the

capitalist system creates the great power of united labour.

Marx traced the development of capitalism from

embryonic

commodity economy, from simple exchange, to its highest forms, to

large-scale production.

And the experience of all capitalist countries, old and

new,

year by year demonstrates clearly the truth of this Marxian

doctrine to increasing numbers of workers.

Capitalism has triumphed all over the world, but this

triumph

is only the prelude to the triumph of labour over capital.

III

When feudalism was overthrown and "free"

capitalist

society

appeared

in

the

world,

it

at

once

became

apparent that this freedom meant a new system of oppression and

exploitation of the working people. Various socialist doctrines

immediately emerged as a reflection of and protest against this

oppression. Early socialism, however, was utopian

socialism. It criticised capitalist society, it condemned and

damned it, it dreamed of its destruction, it had visions of a

better order and endeavoured to convince the rich of the

immorality of exploitation.

But utopian socialism could not indicate the real

solution.

It could not explain the real nature of wage-slavery under

capitalism, it could not reveal the laws of capitalist

development, or show what social force is capable of

becoming the creator of a new society.

Meanwhile, the stormy revolutions which everywhere in

Europe,

and especially in France, accompanied the fall of feudalism, of

serfdom, more and more clearly revealed the struggle of

classes as the basis and the driving force of all

development.

Not a single victory of political freedom over the

feudal

class was won except against desperate resistance. Not a single

capitalist country evolved on a more or less free and democratic

basis except by a life-and-death struggle between the various

classes of capitalist society.

The genius of Marx lies in his having been the first to

deduce from this the lesson world history teaches and to apply

that lesson consistently. The deduction he made is the doctrine

of the class struggle.

People always have been the foolish victims of

deception and

self-deception in politics, and they always will be until they

have learnt to seek out the interests of some class or

other behind all moral, religious, political and social phrases,

declarations and promises. Champions of reforms and improvements

will always be fooled by the defenders of the old order until

they realise that every old institution, however barbarous and

rotten it may appear to be, is kept going by the forces of

certain ruling classes. And there is only one way of

smashing the resistance of those classes, and that is to find, in

the very society which surrounds us, the forces which can -- and,

owing to their social position, must -- constitute the

power capable of sweeping away the old and creating the new, and

to enlighten and organise those forces for the struggle.

Marx's philosophical materialism alone has shown the

proletariat the way out of the spiritual slavery in which all

oppressed classes have hitherto languished. Marx's economic

theory alone has explained the true position of the proletariat

in the general system of capitalism.

Independent organisations of the proletariat are

multiplying

all over the world, from America to Japan and from Sweden to

South Africa. The proletariat is becoming enlightened and

educated by waging its class struggle; it is ridding itself of

the prejudices of bourgeois society; it is rallying its ranks

ever more closely and is learning to gauge the measure of its

successes; it is steeling its forces and is growing

irresistibly.

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|