|

April 26, 2018

April 28, Day of Mourning for

Workers Killed or Injured on the Job

Affirm the Right to Healthy and Safe

Working Conditions!

PDF

April 28, Day of

Mourning for Workers Killed or Injured on the Job

• Affirm the Right to Healthy and Safe Working

Conditions!

Workers Speak Out in

Defence of Their Rights

• Doug Finnson, President, Teamsters Canada

Rail Conference

• Peter Page, Executive Vice President, Ontario

Network of Injured Workers' Groups

• Simon Lévesque, Health and Safety

Director, FTQ-Construction

• Nathalie Savard, President, Union of Health

Care Workers in Northeastern Quebec

• Geneviève Royer, High School Remedial

Teacher

• Denis St. Jean, National Health and Safety

Officer, Public Service

Alliance of Canada

• Lui Queano, Organizer, Migrante Ontario

• Mike Cartwright, Occupational Health and

Safety Committees of the Hospital Employees' Union and the BC

Federation of Labour

• Bill McMullan, Care Aide, Vancouver Island

• Samantha Cartwright, Care Aide, Prince

George

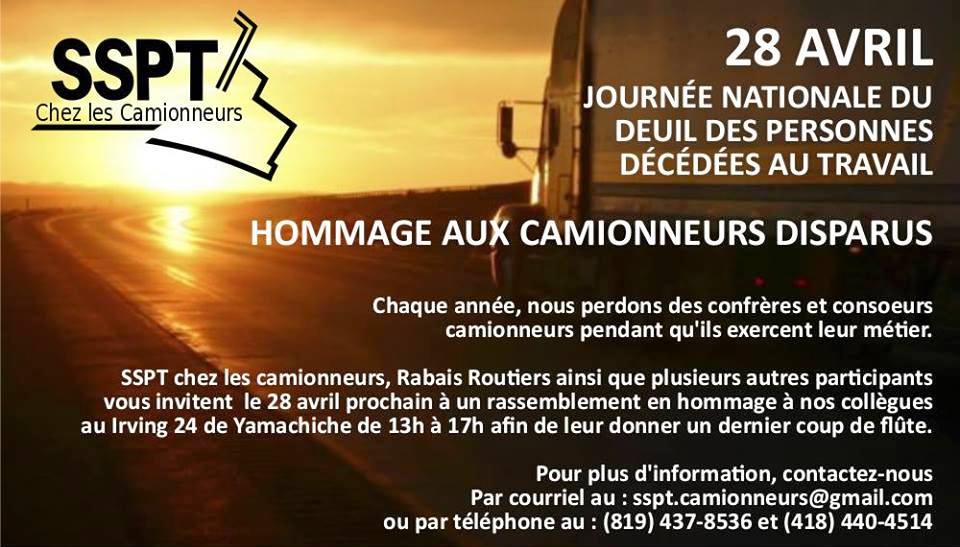

• Quebec Truck Drivers to Commemorate Fellow

Workers Who Died on

the Job - Normand Chouinard, Quebec Trucker

For Your Information

• Fatalities and Injuries at Work in Canada

and Internationally

• Asbestos-Related Deaths - Peggy

Askin, Past President, Calgary and District Labour

Council

April 28, Day of Mourning for

Workers Killed or Injured on the Job

Affirm the Right to Healthy and

Safe Working

Conditions!

Once again this year on the

occasion of April 28,

the Day of Mourning, workers will hold ceremonies and meetings and

observe minutes of silence to mourn the dead and fight for the living.

These events are taking place under very difficult conditions where

those who control and own the production facilities demand absolute

control of the workplaces in order to serve their narrow private

interests, without the workers who do the work having a say and control

over their working conditions. This includes the right to healthy and

safe conditions. How can there be healthy and safe conditions at the

workplace if the independent and organized voice of those doing the

work

is silenced? Monopolies demand unhindered control over production

facilities and reject any intervention by government in their affairs

other than putting forward schemes to pay the rich and using the police

powers of the state to try to crush the struggle of workers for their

rights. Government policies and actions actually compound problems

rather than establishing production standards as a matter of principle

and enforcing health and safety standards without which production

cannot take place. This is done in the name of high ideals such as the

"health of the economy," the "national interest" which, they assert,

require that the monopolies be competitive on global markets. This

leads

to spurious formulas and practices such as self-regulation by industry.

The result of this can be seen, for example, with the railways. Rail is

a sector where the health and safety of workers and the public is

actually most at risk, where self-regulation has led to serious

deterioration in working conditions including workers being forced to

work

routinely beyond the point of exhaustion. Once again this year on the

occasion of April 28,

the Day of Mourning, workers will hold ceremonies and meetings and

observe minutes of silence to mourn the dead and fight for the living.

These events are taking place under very difficult conditions where

those who control and own the production facilities demand absolute

control of the workplaces in order to serve their narrow private

interests, without the workers who do the work having a say and control

over their working conditions. This includes the right to healthy and

safe conditions. How can there be healthy and safe conditions at the

workplace if the independent and organized voice of those doing the

work

is silenced? Monopolies demand unhindered control over production

facilities and reject any intervention by government in their affairs

other than putting forward schemes to pay the rich and using the police

powers of the state to try to crush the struggle of workers for their

rights. Government policies and actions actually compound problems

rather than establishing production standards as a matter of principle

and enforcing health and safety standards without which production

cannot take place. This is done in the name of high ideals such as the

"health of the economy," the "national interest" which, they assert,

require that the monopolies be competitive on global markets. This

leads

to spurious formulas and practices such as self-regulation by industry.

The result of this can be seen, for example, with the railways. Rail is

a sector where the health and safety of workers and the public is

actually most at risk, where self-regulation has led to serious

deterioration in working conditions including workers being forced to

work

routinely beyond the point of exhaustion.

Workers are rejecting the dictate that they have no

role to

play in determining their conditions of work. In particular, they

are organizing to smash the silence about their conditions, both

amongst

themselves at the workplaces and at the level of public opinion itself.

They are publicly explaining what their issues are and how they are

fighting for

themselves and society.

They are opposing the disinformation of the monopoly media and putting

forward

demands that will change the situation in their favour and in favour of

society. The participation of all is required in actions

that build a united and organized force in defence of their rights. In

doing so, they seek to avoid being caught in various traps designed

by the monopolies and governments in their service to paralyze their

initiative, such as engaging

exclusively in filing grievances and fighting arbitrations, which among

other things monopolies are using to drain unions' finances. Workers

are increasingly

going into the arena of public opinion to defend and affirm their right

to safe and healthy conditions and their right to adequate compensation

at a

Canadian standard in the face of increasing workplace injuries and

work-related illness.

In this organized struggle

for their rights workers

argue that safe and healthy working conditions and adequate

compensation for injured workers are an integral part of workers'

exchange with their employer -- their capacity to work in return for

definite conditions that are acceptable to them. Insinuations and

outright accusations that the

problem is the behaviour of workers and that it is the workers who are

to blame for accidents and occupational diseases is a frontal attack on

the conditions of this exchange. It creates an untenable situation with

respect to relations of production in the workplace and in society. In this organized struggle

for their rights workers

argue that safe and healthy working conditions and adequate

compensation for injured workers are an integral part of workers'

exchange with their employer -- their capacity to work in return for

definite conditions that are acceptable to them. Insinuations and

outright accusations that the

problem is the behaviour of workers and that it is the workers who are

to blame for accidents and occupational diseases is a frontal attack on

the conditions of this exchange. It creates an untenable situation with

respect to relations of production in the workplace and in society.

Every day, workers find themselves confronted with the

need to reverse the situation in their favour with regard to their

health and safety and that of the public by increasing their resistance

and fighting for a new direction for the economy. Workers are finding

ways and means to speak out and smash the silence on their working

conditions.

The slogan Our Security Lies in the

Fight for the Rights of All guides

them to build unity in action and affirm their rights and the rights of

all.

On April 28, workers express their determination

to affirm their right to healthy and safe working conditions!

Workers

Speak Out in Defence of Their

Rights

Doug Finnson, President, Teamsters

Canada Rail

Conference

The number one issue is disciplining of workers, the

treatment of the workers who get injured. Health and safety, according

to the employer, is our responsibility. When a worker gets injured,

they say, "You hurt yourself, you injured yourself," and the worker

gets

disciplined. I think that employers purposely do not understand what

health

and safety is. When they say that they are going to put more emphasis

on health and safety, what that translates into is that they are going

to discipline more workers. Basically they want to be able to blame the

workers for everything. It seems that there is no appreciation of the

fact that we should be doing things so that injuries do not take place,

not waiting for an injury to happen. It makes no sense to me that we

are so reactive when it comes to health and safety. It is also a

symptom of lack of proper legislation that the employer has so much

control over health and safety in the rail industry. I think too that

the employers minimize what is taking place in terms of the true number

of

injuries that are taking place. When the railroads get into trouble,

when something terrible happens, they hide behind statistics, that we

went so many thousands of miles without an accident.

Health and safety problems are very often fatigue

related. We have to get out of the pattern which exists in the rail

industry, that when workers feel fatigued, when fatigue sets in in the

workplace, it is a "work now grieve later" situation. That should not

be

a "work now grieve later" situation. Workers find themselves working in

situations where

they should not. They are forced to work overtime or work longer than

they are supposed to, longer than the schedule, longer than what the

contract says they are supposed to, that is "work now grieve later."

You

should be able to stop, to be able to say that someone else should run

that train for me. We are fighting fatigue all the time.

We have to tell workers that health and safety is ours.

It is our broken body, not the company's body. We have to work to get

the message across. In our work we inform, we educate, we build

confidence in the workers' ability. And they have to be active in the

union. It is only if you are active that you understand what we have to

deal with

right now. To be active in the union is essential.

Peter Page, Executive Vice President,

Ontario Network

of Injured Workers' Groups

The Ontario Network of Injured Workers' Groups' launch of province-wide

organizing campaign "Workers' Comp Is a Right" on September 11-12, 2017

coincides with the return of MPPs

to the Ontario Legislature.

Since last August, the Ontario Network of Injured

Workers' Groups (ONIWG) has had this campaign called "Workers' Comp Is

a Right!" We decided on three demands that we present to the three

parties that could form the government, to ask what they would do about

them.

The three issues are:

pre-existing conditions; that

there should be no cuts based on phantom jobs, what they call deeming;

and that they have to listen to the injured worker's doctor. The issue

with pre-existing conditions is that the Workplace Safety Insurance

Board (WSIB) is reducing the benefits

of workers by claiming that the workers had a pre-existing condition

prior to

getting injured, a bad back for example. You may have worked 25

years as a mover and your back never bothered you once. Then you have

an accident, you hurt your back, and they say that this is because of a

pre-existing condition that you had -- you had scoliosis, whatever --

and

they reduce your benefits. The three issues are:

pre-existing conditions; that

there should be no cuts based on phantom jobs, what they call deeming;

and that they have to listen to the injured worker's doctor. The issue

with pre-existing conditions is that the Workplace Safety Insurance

Board (WSIB) is reducing the benefits

of workers by claiming that the workers had a pre-existing condition

prior to

getting injured, a bad back for example. You may have worked 25

years as a mover and your back never bothered you once. Then you have

an accident, you hurt your back, and they say that this is because of a

pre-existing condition that you had -- you had scoliosis, whatever --

and

they reduce your benefits.

The deeming issue is that the Board deems that anyone

is capable of working regardless of whether they are able to do so or

not. There are many examples of workers that we know who will not be

able to return to work or will only return to limited employment which

is not sustainable. The Board uses this to cut benefits to the worker

and

save money.

The third one is that they are using their doctors to

decide on the workers' conditions. Instead of listening to the injured

worker's treating physician, the Board does a paper review with a paper

doctor and decides that the worker is able to go back to work. They

make that decision. They do not take all of the injured worker's health

care issues

into consideration. Say the worker had a broken arm. They say it should

be healed in three months so they cut his benefits even if he still has

ongoing issues and his physician says that he is not able to return to

work.

So far, we have met with

over 23 MPPs in Ontario --

Liberals, Conservatives and NDP -- and we will be having more meetings

with candidates of all parties in regards to the issues that injured

workers want addressed by whoever forms the government. So far, we have met with

over 23 MPPs in Ontario --

Liberals, Conservatives and NDP -- and we will be having more meetings

with candidates of all parties in regards to the issues that injured

workers want addressed by whoever forms the government.

I want to say, by the way, that the WSIB is fully

funded now. There is no more unfunded liability yet injured workers are

still being denied benefits, even more so now. The Board wants to

be 120 per cent funded. They did not get this money by raising the

assessment rates of the employers. They got the money from denying

benefits to

injured workers. It is the cutting of injured workers' benefits that

has resulted in the Board having a fully funded system. And it is now

taking five to six years to adjudicate claims.

We are saying that compensation is a right. Workers

deserve to be treated with justice and dignity.

Simon Lévesque, Health and Safety Director,

FTQ-Construction

Day of Mourning march to National Assembly in Quebec City, April 28,

2015.

What comes to mind first and foremost is that the main

killer in the construction industry is asbestos. We have it

everywhere in the construction sector. They put it everywhere in the

buildings, from the 1950s to the early 1980s. Our workers are

exposed to materials that contain asbestos. At the beginning of

the 1990s, it was acknowledged that this was a problem, measures

were taken in construction work; low, medium and high risk work was

established. Everyone agreed that it was a sneaky disease, that it took

a long time before the disease broke out. The latency period for

developing cancer caused by asbestos -- mesothelioma or pleural

cancer -- is between 15 and 30 years. You arrive at your

retirement to learn that you suffer from asbestosis. There are cases

where mesothelioma is not recognized as being related to asbestos and

work. We have to fight to get it recognized. In addition, the standard

of asbestos that is allowed in the air is ten times higher in Quebec

than

in the rest of Canada. We are asking the government to change the

standard to at least meet the Canadian standard. It is the economic

argument that is given, that we have been producers of asbestos for a

long time, and it was said that it was not dangerous. Even today, it's

difficult to get inspectors on asbestos cases, even though the

government days it's a

priority. The reason is that there is such a long latency

period, there is no perception of an immediate danger.

Construction is still the

sector with the highest

number of fatalities at work per year. We are working hard to change

the behaviour of employers. The level of prevention that is being done

is stagnating. If the employers are not told by the inspectors to

change their methods, if they do not receive warnings, they do not

move. We want health and safety to be taken up by the industry as a

whole, and with the

involvement of workers. The big employers in construction do not want

this to happen. They want to keep their management rights. For us, at

this time, the taking up of responsibility by the industry means that

construction sites would have prevention representatives. The position

of prevention representative is included in the Occupational Health

and Safety Act, but was never promulgated as far as

construction is concerned. We managed to

win them on the sites of 500 or more workers, but

the pressure is huge from the employers not to have any, so

that there is no space for workers on the sites even if these are the

conditions we are working under. There has been progress at

Hydro-Québec, there is a dialogue, a change of culture. But for

most of the big companies, there is a refusal to work with the unions. Construction is still the

sector with the highest

number of fatalities at work per year. We are working hard to change

the behaviour of employers. The level of prevention that is being done

is stagnating. If the employers are not told by the inspectors to

change their methods, if they do not receive warnings, they do not

move. We want health and safety to be taken up by the industry as a

whole, and with the

involvement of workers. The big employers in construction do not want

this to happen. They want to keep their management rights. For us, at

this time, the taking up of responsibility by the industry means that

construction sites would have prevention representatives. The position

of prevention representative is included in the Occupational Health

and Safety Act, but was never promulgated as far as

construction is concerned. We managed to

win them on the sites of 500 or more workers, but

the pressure is huge from the employers not to have any, so

that there is no space for workers on the sites even if these are the

conditions we are working under. There has been progress at

Hydro-Québec, there is a dialogue, a change of culture. But for

most of the big companies, there is a refusal to work with the unions.

The prevention representative is nominated by the union

and is someone

who

is constantly there, who is aware of everything that happens, who makes

sure that accidents are reported. He is there mainly to try to make

sure that accidents do not happen. Also, he protects workers in the

context where workers have no job security. There is a bond of trust

with the representative, who is not there to act like a policeman on

the

building sites.

In current conditions having a prevention representative

has become even more

important. Things have changed on construction sites. In the

not-too-distant past, there were workers' actions on the construction

sites against employers who were intimidating workers. When

that went beyond the limits, it was not uncommon for workers to refuse

to work and say that the work would not

resume if the employer's representative carrying out intimidation was

not

excluded from the job site. Now, as soon as we do that, we will

be sued. We are the ones being called bullies. It is

necessary for workers to regain their role to uphold health and safety

on construction

sites.

Nathalie Savard, President, Union of Health Care

Workers in Northeastern Quebec

There is a lot of work to be done regarding the health

and safety of our members.

Our members often face violence, particularly in the

Residential and Long-Term Care Centres (CHSLDs) from patients who

become aggressive, families who become aggressive with us too.

Employers organize occupational health and safety committees, I think

it's mainly in order to look good. When we come to discuss substantive

issues such

as violence against nurses, particularly in the CHSLDs, prevention

problems, the lack of

inspection of lifting devices that we are using with patients, these

are things that do not receive the needed attention. It is the same

thing for hazardous materials that we must use. We have charts

regarding the use of this

material that explain what to do if there are problems, and the charts

are not getting updated. A main issue is lack of training, for example

for nurses who go to work in people's homes. There is a lack of

training to deal with patients who become violent. This is not the

fault of the patients, it is caused by their dementia. It seems like

there is a

lack of political will to deal with these issues.

Also, the pressure is very strong because of the

shortage of personnel, the lack of resources. Budgets are not set

according to the

needs. We are also seeing more and more problems of psychological

health. We try to get them recognized as an occupational disease, but

it is not easy. In terms of mental health, there is a lot of prejudice

on the part of

employers, and there is also prejudice in the general population.

Recently, at the level of the Occupational Health and Safety Act,

those

who

work

in

the

health

care system have finally been recognized as a

priority

group because of musculoskeletal disorders and psychological health

problems so we hope that from now on things are going to move quickly

in

order to sort out the problems. [In the Act, priority groups are

those that are considered the most hazardous, needing prevention

mechanisms, such as the mining, forestry and chemical industries, etc.

-- WF Note.]

There is also the issue of safety for expectant

mothers. Hospitals are

trying to keep more workers who are pregnant in the workplace. But with

the shortage of nurses, this is putting the nurses who are at work

under a lot of pressure. Often we must intervene to enforce the

limitations on what is expected of these workers. We have to protect

our members on this issue.

Nurses are having to work faster and faster

as there are fewer and fewer people. It's a complex situation. All the

problems

society is facing end up in the health care system. If we want to keep

our people healthy, we have to take care of them. There has to be a

focus

on training. There must to be health and safety committees including

the union and the employer where problems can be raised and solved. We

have to provide good service to patients and that needs to be

done in a safe environment. That is the main issue.

Geneviève Royer, High School Remedial Teacher

The main problem is that none of the arrangements that

are being made in education are based on the needs that teachers have

identified. The main need in the short term is the decrease in the

teacher-pupil ratio. This demand has been put forward at least

since 1995, when teachers identified that in the social context in

which we live classroom size must be reduced. They need this to

provide quality education and to identify students in difficulty and

also to be able to identify the help that students need. We cannot

identify difficulties because we have 30 students in a class. When

we do identify difficulties the resources are not there. This is the

main

problem that exists and this is creating the problem of burnout that is

more and more common among teachers. To avoid solving the problem,

there is the ideological offensive that says there is no money and so

we have to manoeuvre in the absence of the necessary funding. The

reforms that were instituted, which were imposed on the teachers,

were that teachers should be able to function with 30 students,

making six groups of five, and so on. This is a diversion because a

decrease in the teacher-student ratio would mean investing in

education, new teachers being hired, new classes opening up. It would

be something positive but in the modus

operandi of the state this is

not positive, it

is an expense that must be avoided.

At the same time as we have

this

refusal to reduce the teacher-student ratio, we also have the

phenomenon, which we saw in health care with deinstitutionalization in

the 1990s, of standardization of students.

Standardization means that the student has to be in a regular class.

When I started teaching there

were a lot of specialized classes. The pretext for standardization was

to say that students were marginalized in specialized classes so they

needed to be introduced into regular classes. It was a pretext to close

the specialized classes year after year and integrate these students,

but without the associated services required to meet their needs. At the same time as we have

this

refusal to reduce the teacher-student ratio, we also have the

phenomenon, which we saw in health care with deinstitutionalization in

the 1990s, of standardization of students.

Standardization means that the student has to be in a regular class.

When I started teaching there

were a lot of specialized classes. The pretext for standardization was

to say that students were marginalized in specialized classes so they

needed to be introduced into regular classes. It was a pretext to close

the specialized classes year after year and integrate these students,

but without the associated services required to meet their needs.

In addition, the anti-social offensive has an effect on

families, on children. There may be a group of 30 with 10

to 15 students who have special needs that are not being

addressed. When the needs are not met, it becomes an issue of

behaviour, it becomes the problem of the teacher who must "learn to

manage" their classes,

etc. The overload, which is the result of the destruction of

educational arrangements, is presented as a personal problem of the

teacher. With the anti-social offensive we get a lot of students who do

not eat breakfast in the morning, we have parents who are themselves in

crisis, without jobs, needing help to sort out their lives. In this

context,

collectives are targeted. It is the parents who must supposedly learn

to raise their children, etc. Enemies are created and targeted while

the organization of the education system is unscientific and

irrational. This puts tremendous pressure on teachers. There has been a

huge increase of long-term absences among teachers. It is not uncommon

for a

teachers to be absent from class for a year or two. It is exhausting

for teachers to have young people in front of them and to know that

they are not meeting their needs. There is a form of violence that sets

in; the group becomes restless, the teachers go into survival mode,

they start expelling students. This is in contradiction with the

pedagogical

professionalism inherent in teaching. With this destruction, many

parents choose to go to the private system because there is more

stability. There is an exodus from the public to the private sector. To

cope with this exodus, teachers engage in many activities that go

beyond their workload. There is the issue of lowering of standards in

the

educational system. For example, there is pressure from the authorities

to give students a passing grade at any cost. Teachers object to this

lowering of standards in education, which is an attack on their dignity

as teachers.

What keeps us going is the collective. Teachers rely on

one another, they help each other to deal with different situations.

What I see in this situation is that our tasks have increased so much

and our work has become so complex in the context of the anti-social

offensive that we would be able to run the schools. We manage the

money. We

manage the activities of the students. We manage relations with the

parents. We learn to look for the strengths that each teacher has to

solve the problems we face. Also, in times of negotiations, teachers

engage in organized trade union struggle in order to improve their

working conditions which are the learning conditions of the students.

Denis St. Jean, National Health and Safety Officer,

Public Service Alliance of Canada

Each year we adopt a special theme to focus on a health

and safety issue that is important for our workers. This year, we

selected one that is very important in the federal public service:

harassment and violence in the workplace. We are asking that the law

require that the workplace be safe and healthy. For instance, we want

legislation that

will support women workers who report incidents of violence and

harassment. We are carefully examining Bill C-65 on sexual harassment

and violence that is now before the House of Commons and the outcome of

the public consultations currently being conducted by the Ministry of

Labour across Canada.

Over the years we have been surveying our members at

our national and regional health and safety conferences. The response

of our members is number one, violence and harassment. The second is

the issue of mental health in the workplace and the third is the lack

of training on these topics.

Harassment and violence come in all forms. We are

obviously talking about physical violence, but we are also talking

about psychological violence. We are talking about intimidation,

threats of reprisal, unacceptable behaviour, incivility. This is

happening mainly as an issue of power at the workplace, where people in

support positions are

primarily targeted by those who have more power than them. Most cases

of intimidation at the workplace are cases of a person who is in

position of power, like people who are part of management, versus a

person who has less power. It is an abuse of power, a demonstration of

the kind of balance of power that we see at the workplace. In the

federal public service, surveys are conducted once every two years and

the results are consistent, with almost one in five people in the

public service reporting being harassed in the workplace and 25

per cent

reporting they did not take any action to try to solve the problem of

harassment. This indicates a lack of trust in existing processes and a

culture where harassment is tolerated as a normal condition of work.

The only way to counteract this lack of power is

obviously to be part of a union, to be able to find solutions, whether

through collective agreements, the legislative changes we are demanding

and the legal remedies.

Lui Queano, Organizer for Migrante Ontario

Demonstration in Toronto, September 15, 2017.

For migrant workers, a main problem is that they are

not given proper safety equipment. Many are working on farms and are

being exposed to fertilizers without being given the proper protective

equipment. This is a very basic thing, but it is not being provided in

an adequate manner. They are using all these fertilizers but they are

not

provided with personal protective equipment, and if they are it is

often used and worn out equipment, not new. They cannot ask for new

ones. These workers are seasonal and the government is not paying

proper attention to their safety. They are amongst the most vulnerable

workers.

Migrante right now is doing a lot of community safety

education with these workers. We are also educating them on their

rights in the work places. We are encouraging them to inform us when

there

are issues. Migrante is very much willing to

help them, including on the legal front. We have seminars for them, in

cooperation with Migrant Resources Centre Canada. We invite

workers to drop in there to learn, to educate themselves about the

importance of protection, so that they know what they need to know

about their jobs, so that they are not afraid to talk about their

conditions at work. Migrante Canada visits migrant workers. For example

we

found out in Prince Edward Island that migrant workers were working in

the fishing industry and had no organization. These were mostly

Filipino

workers. Migrante is helping them to organize themselves.

We are also coordinating with the Caregivers Action

Centre to demand that the federal government immediately repeal a

section of the law that denies permanent residency to immigrants with

disabilities. This is a section of the Immigration and Refugee

Protection Act, which denies permanent residency to an entire

family if one

member is sick or has a disability that would pose an "excessive

demand" on Canada's health care system. The caregivers spend their

money to come to Canada, perform a very valuable and

needed service, only to find out that they are not accepted.

Migrante organizes so that migrant workers can speak

out, organize, be more confident, have a voice.

Mike Cartwright, Occupational Health and Safety

Committees of the Hospital Employees' Union

and the BC Federation of

Labour

In health care the biggest challenge to health and

safety is the lack of staff. A significant number of our injuries are

due to being short-staffed, understaffed. This is happening to care

aides, recreation workers, housekeepers and kitchen staff, as well as

others. Most are musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs), some cuts and scrapes

and

abrasions but the

majority are MSIs. There is also a significant increase in work-related

stress. There are a lot more injuries in complex care settings, in

seniors' residences, than in hospitals. A lot of the "complex care

homes" are not set up to be complex care. Buildings are not proper for

dementia care. Staff aren't trained properly. There is not enough

staff. You

often have one person doing a two-person lift. Many of the residential

care homes were built back in the '60s and '70s and '80s.

In the private, for-profit residential homes, the owners are in

business

to make money not to spend it so they often don't provide the lifts or

other equipment that workers need to do their jobs safely.

The BC Federation of Labour

Occupational Health and Safety Committee is lobbying

the government to change the Worksafe BC Board and Worksafe regulations

with respect to safe staffing levels, to fatigue levels. We have put in

recommendations for length-of-day language because right now there is

no restriction on how long someone can be at work. The BC Federation of Labour

Occupational Health and Safety Committee is lobbying

the government to change the Worksafe BC Board and Worksafe regulations

with respect to safe staffing levels, to fatigue levels. We have put in

recommendations for length-of-day language because right now there is

no restriction on how long someone can be at work.

The mandate of these two bodies is to raise awareness

so workers know their rights and how to enforce them and to advocate

with government. The HEU Occupational Health and Safety Committee

assisted in creating the

curriculum for our "Know and Enforce Your Rights" course for members in

member to member education sessions. We're also reaching out all across

the province to all locals to make sure that their Joint Occupational

Health and Safety Committees are functioning. We want to educate our

members to be able to combat the attacks by management or the

intimidation by management saying "Just do this" even if it's unsafe.

We want to give our members the tools to say "No, I have the right to

refuse unsafe work. I have the right to know about hazards in my

workplace."

Bill McMullan, Care Aide, Vancouver Island

I work in a group home which is the home of several

individuals. The people that I care for are adults with severe and

profound disabilities, both cognitive and physical. They require full

personal support, with attending medical appointments, meal preparation

and feeding, dressing, bathing, social activities, basically to

interpret their needs

and to see that they get the care that they require.

With regards to our working conditions, the biggest

difficulty that we face is being short-staffed. There is an erosion of

full-time positions. Every year there are more full-time positions

being reconstructed into part-time positions. The wages for care aides

in the community

are lower than the wages in hospitals so there is a

problem of retention.

When they start people often work at multiple worksites and then to

grab some security they will take a part-time job here and there and

everywhere which prevents them from being accessible and available for

full-time jobs and employers take full advantage of that and collapse

full-time jobs. In my sector workers are often isolated from one

another and some of the newest workers are not aware of their rights

and that is also taken advantage of. There are a lot of things that

contribute to diminished health and wellness for workers in my sector.

We have aging equipment -- lifts, slings, modified beds, electric tubs

--

and at the same time you have an aging workforce that is doing

repetitive

work so you need the equipment working.

In this sector there are both private, for-profit

operators and non-profit societies, all funded by government through

Community Living BC (CLBC). The problem is that as service needs change

and an individual

needs more care, CLBC won't fund those increased needs. They force the

agency providing services to cope and the agency downloads that onto

the staff who

have to do more with less. We also have problems with inadequate

training to deal with individuals that are aggressive.

Also, there are some agencies in Community Social

Services, among those that are privately owned, which will deliberately

bring in more aggressive individuals to live in a group home because

the higher the aggression the higher the dollars that they get from

CLBC. It's not uncommon to have

a 20-year-old

female care aide dealing with an aggressive male one on one, and often

the protocol is "lock yourself in a room when they're out of control."

That's the behaviour support plan. Without adequate staff and proper

training workers' safety and the safety of the people we care for is

compromised.

Samantha Cartwright, Care Aide, Prince George

I work in a residential complex care facility

with 58 beds. Most of the people are seniors and about 85 per

cent are in the throes of dementia by the time that they come into

care, unfortunately, because the wait lists are so long. The

other 15 per cent are cognitively well but physically extremely

unwell, so some of them fight you on

care -- "No, you're not using that ceiling lift on me. You can use the

Golvo lift," when the Golvo lift has been deemed inappropriate.

Staffing levels have not changed significantly in the last 20

years, but 20 years ago the physical needs of the residents were

far less than they are now.

Our work is complicated, balancing the needs of the

residents with safety. People with dementia have difficulty

communicating. Water for some people with dementia is actually

terrifying and they can become combative. Bath teams are still single

people. Even when a care plan requires two or three people to deal

with aggressive behaviour,

the bath person still does the bath by herself. Part of it is that the

workers on the bath team are really good at their job and know that if

they have a partner that the resident is not familiar with it will

create a more dangerous situation but if they are on their own they

know how to deal with aggression because they know how to deal with the

person, they have a relationship, they are trusted. Our work has risks

and hazards by its nature.

Our biggest problem is being short-staffed. In our jobs

we need to work as a team and when we are short-staffed, both

chronically and when workers are not replaced when they are absent, we

are expected to figure it out ourselves which creates two problems,

unsafe working conditions and conflict between workers because it is

not possible

for two workers to do the work of four or more.

Quebec Truck Drivers to Commemorate Fellow Workers Who

Died on the Job

- Normand Chouinard, Quebec Trucker -

An important event for Quebec truckers will be held on

April 28, the Day of Mourning for Workers Killed or Injured on

the Job, in the small municipality of Yamachiche, in Mauricie, a

tribute to truck drivers who have died on the road. It is under the

initiative and impetus of the non-profit organization "SSPT chez les

camionneurs" (post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among truckers)

that such a gathering is taking place for the first time.

SSPT chez les camionneurs

was created in 2013 when

driver Patrick Forgues was involved in an accident in which a man died.

The man committed suicide by throwing himself in front of Forgues'

truck. Mr. Forgues was diagnosed with PTSD one month later and his life

was turned upside down. On the initiative of his wife, Kareen

Lapointe, a Facebook page was created to help truckers and their

families to demystify post-traumatic stress disorder. The

organization's Facebook page states, "A year later,

the demand for such a service was such that we started a non-profit

organization called SSPT chez les camionneurs." SSPT chez les camionneurs

was created in 2013 when

driver Patrick Forgues was involved in an accident in which a man died.

The man committed suicide by throwing himself in front of Forgues'

truck. Mr. Forgues was diagnosed with PTSD one month later and his life

was turned upside down. On the initiative of his wife, Kareen

Lapointe, a Facebook page was created to help truckers and their

families to demystify post-traumatic stress disorder. The

organization's Facebook page states, "A year later,

the demand for such a service was such that we started a non-profit

organization called SSPT chez les camionneurs."

People from the trucking industry across Quebec and

elsewhere will finally be able to commemorate those who died on the

road. There will also be testimonials from injured truck drivers, and

support services are going to be offered at the event site. It will

also be an opportunity to smash the silence on the daily working

conditions of truck

drivers and the constant dangers they face. Truck driving is one of the

most dangerous jobs, which still has one of the highest rates of

work-related injuries and fatalities. Recognition of post-traumatic

stress disorder as an occupational disease in trucking is an important

issue as the number of road accidents on North American roads is

increasing,

with huge consequences for the well-being of drivers and the public.

For

Your Information

Fatalities and Injuries at Work in Canada

and

Internationally

The most recent available statistics on fatalities and

injuries at work in Canada are from the Association of Workers'

Compensation Boards of Canada (AWCBC) from 2016.

The statistics show that in 2016 the number of

fatalities at work was 905, up from 852 in 2015 and

slightly down from 919 in 2014. This means 2.47 deaths

every day. The sectors where the number of fatalities were the highest

are construction (203), government services (158), manufacturing (144)

and transportation and storage (82). Of these fatalities, 320 were

due to traumatic injuries and disorders and 567 to diseases, the

greatest number being 427 cases of malignant neoplasms, tumors and

cancers.

Among the 905 dead, six were young workers

aged 15 to 19, twenty aged 20 to 24 and thirty

aged 25 to 29.

In addition to these fatalities, there

were 241,508 claims accepted for lost time due to a work-related

injury or disease, up from 232,629 in 2015 and 239,643

in 2014. These included 7,583 claims from young workers

aged 15 to 19, 22,005 from workers aged 20

to 24

and 24,927 from workers aged 25 to 29. The sectors where

the number of claims accepted for lost time was the highest were health

and social services (43,836), manufacturing (33,084), retail trade

(26,924) and construction (25,645).

The AWCBC defines a time-loss injury as "an injury for

which a worker is compensated for a loss of wages following a

work-related accident (or exposure to a noxious chemical) or receives

compensation for a permanent disability with or without time lost in

his or her employment." To be included in the statistical report, the

injury must

have been accepted by a workers' compensation board or commission

(cases not accepted by a workers' compensation agency are not included

in the reports).

The AWCBC says the number of lost time claims that are

being accepted has been steadily decreasing since 1995

(from 410,464 in 1995 to 241,508 in 2015) while the

number of fatalities has remained 915 a year on average. This

likely indicates a high number of unreported injuries even amongst

unionized workers, of challenged and rejected claims, and the massive

shift of the workforce towards precarious employment of all kinds. This

precariousness of employment is increasing even amongst the workforce

that works for the monopolies as they are subcontracting more of the

work so as to lower the claims of the workers on the value

they produce. These workers are considered as disposable and they are

swiftly replaced when they hurt themselves, the injury often remaining

unreported under the pressure that the subcontractor may lose its

contract with the monopoly if it "causes trouble" by allowing workers'

reports of injuries. In provinces such as Ontario, employers get

"rebates" from the government if they reduce the number of injuries

reported.

According to Worksafe BC, health care assistants or

care aides continue to have the highest rate of injury of any

occupational group. Care aides provide personal care -- bathing,

dressing, feeding, toileting to people with disabilities and seniors in

private homes, group homes, hospitals and seniors' homes. The rate of

injury in this sector

was 8.7 per 100 workers, four times the BC average

of 2.1 per hundred. In a series of meetings through the province

in March in preparation for provincial bargaining which will begin this

year, members of the Hospital Employees Union, which

represents 49,000 health care workers in the province, identified

overwork

and understaffing as their biggest concern and demanded increased

investment in publicly funded and publicly delivered health care.

The compensation system itself has become "a very

litigious, difficult, cumbersome system" representatives of injured

workers point out. The system is also not funded properly, they add.

Workers report that their claims, when they are legally allowed to make

a claim, are systematically being challenged.

Internationally, the latest global figures date from

the XXI World Congress on Safety and Health which took place in

Singapore in 2017. These figures are based on data collected

in 2014-2015 and are included in the report Global Estimates

of Occupational Accidents and Work-related Illnesses 2017

presented to

the Congress.

They indicate that an estimated 2.78 million

work-related fatalities occur annually compared to 2.33 million

estimated in the previous study completed in 2014 which was based

on data from 2010/2011. The estimated global total of fatal

occupational accidents and work-related illness in the 2017 report

reflects

the inclusion of respiratory cases caused by chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease and work-related asthma which were not included in

the 2014 report. For fatal occupational accidents, there are an

estimated 380,500 deaths a year, an increase of 8 per cent

since the previous study. Fatal work-related diseases were at least

five times

higher than fatalities due to occupational accidents. In 2015,

there were 2.4 million deaths due to fatal work-related diseases,

an increase of 0.4 million compared to 2011. Taken together,

circulatory diseases (31 per cent), malignant neoplasms (26 per cent)

and respiratory

diseases (17 per cent) contributed more than three-quarters of

work-related deaths, followed by occupational injuries (14 per cent)

and

communicable diseases (9 per cent). The number of non-fatal

occupational

accidents was estimated to be 374 million, increasing

significantly from 2010.

According to the figures, while the total employment

in 2014 for all countries increased by four per cent compared

to 2010, the number of estimated fatal occupational accidents

increased by about eight per cent to 380,500. In total, it is

estimated that more than 7,500 people die every day; 1,000

from occupational

accidents and 6,500 from work-related diseases. The rate of fatal

occupational accidents increased slightly between 2010

and 2014.

Asia constituted about two-thirds of the global

work-related mortality, followed by Africa at 11.8 per cent and

Europe

at 11.7 per cent. The Americas and Caribbean stood at 10.9

per cent and Oceania at 0.6 per cent.

Neo-liberal free trade agreements and the anti-social

offensive are a major factor in the continued deterioration of living

and working conditions, including health and safety at work, in all

countries. They concentrate decision-making power in the hands of

global oligopolies on a supranational basis. The oligopolies consider

health and safety

regulations as impediments to their drive for profit and domination.

Deaths and injuries take a particularly heavy toll on workers in the

countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean due to their

super-exploitation.

The International Trade Union Confederation reported

two years ago that global oligopolies such as Samsung, Apple,

Walmart and others directly employ barely six per cent of the

workers who create the value of their global empires. The other 94

per cent work for smaller companies who subcontract to the monopolies.

These workers face even worse conditions, without any support when it

comes to health and safety.

The situation is very similar in Canada where the

working class has been divided into arbitrary categories such as

"independent contractor," "temporary foreign worker," "undocumented

worker," among others. Employers use these designations, along with the

increase in short-term and casual jobs and other forms of precarious

employment, to

impose increasingly unsafe conditions.

Asbestos-Related Deaths

- Peggy Askin, Past President, Calgary

and District Labour Council -

One hundred and sixty-six workers were killed on the

job or died from work-related illnesses in Alberta in 2017.

Eighty-three died from work-related disease, with 67 deaths

related to asbestos exposure, six deaths from respiratory diseases

not related to asbestos, and 10 firefighters, nine of whom died of

cancer.

Firefighters waged a protracted fight to have certain cancers

recognized as arising from their work and exposure to carcinogens.

Workers employed in construction had the highest rate of death from

accidents or work-related disease.

"It has been estimated that

asbestos was responsible

for approximately 1,900 lung cancer cases and 430

mesothelioma

cases in Canada in 2011," the Canadian government's Regulatory

Impact Statement states. At this time, workers from several

generations, from those in their fifties to those in their eighties are

dying

from respiratory diseases directly related to workplace exposure to

asbestos. This disease is latent, the fibres remain in the lungs for

decades, and then start to ravage the lungs and the lining of the lung. "It has been estimated that

asbestos was responsible

for approximately 1,900 lung cancer cases and 430

mesothelioma

cases in Canada in 2011," the Canadian government's Regulatory

Impact Statement states. At this time, workers from several

generations, from those in their fifties to those in their eighties are

dying

from respiratory diseases directly related to workplace exposure to

asbestos. This disease is latent, the fibres remain in the lungs for

decades, and then start to ravage the lungs and the lining of the lung.

Affected workers include those in construction who

built and renovated every industrial, commercial and residential

building and were exposed to asbestos in the course of their work.

Workers in the petroleum and mining sectors were also exposed to

asbestos. Workers in BC and the western provinces worked in the

asbestos mines in Cassiar,

BC from the early 1950s until the mining operation closed

in 1992.

These are generations of workers who should not have

been exposed to asbestos as it is a known fact that studies conducted

in the 1920s and 1930s revealed the danger of exposure to

asbestos.[1]

The callousness of governments in the service of the

monopolies when it comes to workers' lives is starkly revealed in the

"cost-benefit statement" with regard to banning asbestos. It says, "The

government administrative costs are estimated to be about $4

million, and the administrative and compliance costs for the

construction and

automotive sectors are estimated to be about $30 million. It is

also estimated that preventing a single case of lung cancer or

mesothelioma provides a social welfare benefit valued at over $1

million today. Given the latency effects of asbestos exposure, benefits

would not be expected to occur until 10 to 40 years after the

coming into force of the proposed regulations in 2019; therefore,

the present value of future benefits per case would be lower than the

value of current cases. For example, $1 million per case

in 2050 would be valued at about $380,000 per case today

(discounted at 3 per cent per year). Therefore, if the proposed

regulations can prevent at least five cases of lung cancer or

mesothelioma each year (5.3 cases on average), for a period of at

least 17 years, then the health benefits for these sectors ($34

million) would be expected to justify the associated administrative and

compliance costs ($34 million)."

Quebec workers in the asbestos mines waged a militant

and courageous five-month long illegal strike in 1949, against

the dangerous working conditions they faced. The organized workers'

movement has fought and is still fighting that employers be held to

account for the death toll these lung diseases are causing. Workers

continue to

fight to put an end to dangerous working conditions and empower

ourselves to hold corporations and governments to account.

Asbestos use will finally be banned in Canada

in 2018, almost a century after the deadly consequences of

exposure first became known.

The following are key dates in the history of

asbestos use in Canada.

1920s : The Metropolitan Life Insurance

Co. sets up the Department of Industrial Hygiene at McGill University.

Asbestos is believed to be making workers ill and causing a "dust

disease" of the lungs.

1984: An Ontario Royal Commission suggests a

ban on crocidolite and amosite asbestos fibre, but suggests that

chrysotile can be used if there are controls on dust.

1987: The International Agency for Research on

Cancer declares asbestos a human carcinogen.

1998: The Rotterdam Convention, a treaty on

certain hazardous chemicals and pesticides in international trade, is

adopted and opened for signatures.

2004: The Rotterdam Convention comes into force.

2005: A European Union-wide ban on chrysotile

asbestos takes effect.

2018: Canada finally bans asbestos, with

regulations to come into effect in 2019.

Note

1. "A look at Canada's 140

year history

with asbestos," Canadian Press,

December 15, 2016.

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: office@cpcml.ca

|