|

April 25, 2015 - No. 17 Supplement Canada's Economic Existential Crisis• Statistics Canada Notes Disturbing

Economic Trends

• What Statistics Canada Says About the Downturn in Canadian Manufacturing from 1998 to 2008 Canada's Economic Existential Crisis Statistics Canada Notes Disturbing Economic Trends  In recent publications, Statistics Canada reports that the service industry has climbed to become the most dominant sector by far at 78.4 per cent of the economy. In contrast, the manufacturing sector has consistently shrunk in recent time to account now for only 9.4 per cent of the economy. Only 1.6 million workers out of the present workforce of 19 million are currently employed in manufacturing. The current manufacturing percentage and number of workers contrast with a much larger presence in the 1970s and early 1980s when factory employment averaged around 20 per cent of the economy. The statistics reflect an uneven development of Canada's economy that suggest it is relying heavily on imported manufactured goods to replace those previously made within the economy. This phenomenon drains value out of the economy and weakens it. The share of people working on the services side of the economy at 78.4 per cent is the highest on record after several decades of increases. Three quarters of working Canadians now hold jobs in sectors such as retail, food services, education, professional services and health care. The value they produce can only be realized within an economy with robust manufacturing or generally speaking an all-sided economy. This is not the case and poses a serious challenge.

The declining absolute number of manufacturing workers and the lessened relative strength of the sector in the economy cannot be explained by rising productivity alone, as the population of Canada and the size of the workforce have greatly increased. The statistics show that the manufacturing sector is under deliberate attack by monopoly right. This is not to suggest the service sector should be weakened but that the working class, especially the unemployed, underemployed and the millions not in the workforce for whatever reasons should be mobilized to work to the best of their abilities. Almost two million workers are unemployed or are involuntarily working part-time while 10 million other Canadians over the age of 15 do not participate in the workforce. Those 12 million Canadians represent enormous potential for value not only to strengthen the manufacturing sector but also to be available to work if there were increased investments in social programs and public services. A fully mobilized workforce would put upward pressure on reproduced-value (the claims of workers on the value they produce), particularly in the poorly paid sections within the service industry. This would assist in the realization of value in the overall economy. Unemployment and Part-Time Work -- A Look at March StatisticsAccording to Statscan, nearly half of all male workers between the ages of 25 and 54 who are working part-time do so not out of choice but necessity. This statistic, coupled with the persistently high rate of unemployment of 6.8 per cent of the declared workforce, means massive amounts of potential value that the working class could produce if employed fully, is consistently being lost. Statscan says all new employment during March, 2015 was in part-time work. Part-time positions rose by 56,800 while full-time work fell by 28,200. Not only male workers complain of a lack of full-time employment; 35.6 per cent of core-aged (25-54) women working in part-time positions say they are doing so involuntarily. Large numbers of both male and female workers, working part-time, unemployed, or out of the workforce, are unable to find full-time work. Apparently, this rate is higher than 2007 levels before the 2008 economic crisis, from which the economy has allegedly recovered. In actual numbers, more than half a million core-aged workers would prefer full-time jobs but are languishing in part-time work. Also, 1.3 million workers have no work at all and hundreds of thousands if not millions more have abandoned the workforce altogether. In the goods-producing sector, manufacturing as a share of total employment dwindled to a record low. It fell to 9.4 per cent in March, down from 15 per cent in the 1990s and 19 per cent in the 1970s and early 1980s. Statscan says growth in services has often been grouped into two types of work -- those demanding higher skills that pay above-average wages (like engineers and architects), and those that require fewer skills and pay below-average wages (such as hotel and fast-food workers). The country's workforce participation rate in March was 65.9 per cent. The population over 15 was 29 million while the declared workforce was 19 million. Statscan says, all told, more than half a million core-aged workers would prefer full-time jobs rather than the part-time work they presently have. In the two main oil-producing provinces, Alberta and Newfoundland, unemployment rates rose to 5.5 per cent and 13.3 per cent, respectively. The Bank of Canada's business outlook survey, released in mid-April, showed hiring intentions of major companies are the weakest since 2009. Statistics Canada -- Labour Force Characteristics by

Age and Sex

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

February 2015

|

March 2015

|

Standard error1

|

February to

March 2015

|

March 2014 to

March

2015

|

February to

March 2015

|

March 2014 to

March

2015

|

|

thousands (except

rates)

|

change in

thousands

(except rates)

|

% change

|

|||||

|

Both sexes, 15

years

and over

|

|||||||

|

Population

|

29,160.7

|

29,183.3

|

...

|

22.6

|

303.8

|

0.1

|

1.1

|

|

Labour force

|

19,197.6

|

19,224.0

|

29.0

|

26.4

|

111.9

|

0.1

|

0.6

|

|

Employment

|

17,885.9

|

17,914.6

|

28.7

|

28.7

|

138.1

|

0.2

|

0.8

|

|

Full-time

|

14,488.2

|

14,460.0

|

39.2

|

-28.2

|

110.5

|

-0.2

|

0.8

|

|

Part-time

|

3,397.8

|

3,454.6

|

36.1

|

56.8

|

27.6

|

1.7

|

0.8

|

|

Unemployment

|

1,311.7

|

1,309.3

|

24.6

|

-2.4

|

-26.3

|

-0.2

|

-2.0

|

|

Participation rate

|

65.8

|

65.9

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

-0.3

|

...

|

...

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

6.8

|

6.8

|

0.1

|

0.0

|

-0.2

|

...

|

...

|

|

Employment rate

|

61.3

|

61.4

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

-0.2

|

...

|

...

|

|

Part-time rate

|

19.0

|

19.3

|

0.2

|

0.3

|

0.0

|

...

|

...

|

|

Youths, 15 to

24

years

|

|||||||

|

Population

|

4,446.9

|

4,443.8

|

...

|

-3.1

|

-43.2

|

-0.1

|

-1.0

|

|

Labour force

|

2,870.9

|

2,872.4

|

16.9

|

1.5

|

6.8

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

|

Employment

|

2,488.4

|

2,499.0

|

15.6

|

10.6

|

23.3

|

0.4

|

0.9

|

|

Full-time

|

1,266.2

|

1,262.7

|

18.8

|

-3.5

|

-14.6

|

-0.3

|

-1.1

|

|

Part-time

|

1,222.1

|

1,236.3

|

19.8

|

14.2

|

37.9

|

1.2

|

3.2

|

|

Unemployment

|

382.6

|

373.3

|

14.5

|

-9.3

|

-16.6

|

-2.4

|

-4.3

|

|

Participation rate

|

64.6

|

64.6

|

0.4

|

0.0

|

0.7

|

...

|

...

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

13.3

|

13.0

|

0.5

|

-0.3

|

-0.6

|

...

|

...

|

|

Employment rate

|

56.0

|

56.2

|

0.3

|

0.2

|

1.0

|

...

|

...

|

|

Part-time rate

|

49.1

|

49.5

|

0.7

|

0.4

|

1.1

|

...

|

...

|

|

Men, 25 years

and

over

|

|||||||

|

Population

|

12,087.5

|

12,099.8

|

...

|

12.3

|

168.9

|

0.1

|

1.4

|

|

Labour force

|

8,674.0

|

8,655.8

|

15.3

|

-18.2

|

63.0

|

-0.2

|

0.7

|

|

Employment

|

8,139.5

|

8,135.2

|

16.5

|

-4.3

|

76.3

|

-0.1

|

0.9

|

|

Full-time

|

7,497.2

|

7,486.7

|

21.9

|

-10.5

|

102.2

|

-0.1

|

1.4

|

|

Part-time

|

642.3

|

648.5

|

17.9

|

6.2

|

-25.9

|

1.0

|

-3.8

|

|

Unemployment

|

534.5

|

520.6

|

14.3

|

-13.9

|

-13.3

|

-2.6

|

-2.5

|

|

Participation rate

|

71.8

|

71.5

|

0.1

|

-0.3

|

-0.5

|

...

|

...

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

6.2

|

6.0

|

0.2

|

-0.2

|

-0.2

|

...

|

...

|

|

Employment rate

|

67.3

|

67.2

|

0.1

|

-0.1

|

-0.3

|

...

|

...

|

|

Part-time rate

|

7.9

|

8.0

|

0.2

|

0.1

|

-0.4

|

...

|

...

|

|

Women, 25

years and

over

|

|||||||

|

Population

|

12,626.2

|

12,639.8

|

...

|

13.6

|

178.2

|

0.1

|

1.4

|

|

Labour force

|

7,652.7

|

7,695.8

|

16.5

|

43.1

|

42.1

|

0.6

|

0.6

|

|

Employment

|

7,258.1

|

7,280.4

|

16.0

|

22.3

|

38.5

|

0.3

|

0.5

|

|

Full-time

|

5,724.7

|

5,710.6

|

24.9

|

-14.1

|

22.8

|

-0.2

|

0.4

|

|

Part-time

|

1,533.4

|

1,569.8

|

23.7

|

36.4

|

15.7

|

2.4

|

1.0

|

|

Unemployment

|

394.6

|

415.4

|

13.2

|

20.8

|

3.6

|

5.3

|

0.9

|

|

Participation rate

|

60.6

|

60.9

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

-0.5

|

...

|

...

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

5.2

|

5.4

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

0.0

|

...

|

...

|

|

Employment rate

|

57.5

|

57.6

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

-0.5

|

...

|

...

|

|

Part-time rate

|

21.1

|

21.6

|

0.3

|

0.4

|

0.1

|

...

|

...

|

What Statistics Canada Says About the Downturn in Canadian Manufacturing from 1998 to 2008

TML Weekly is posting below Part Two of "Canada's Economic Existential Crisis" by K.C. Adams which provides excerpts from a Statistics Canada study released in 2009 that deals with the situation in the manufacturing sector for the decade following 1998. Ellipses to indicate a break in the Statscan item have been left out. For the complete document including references and footnotes click here. For Part One in the series, "Problems in the Manufacturing Sector," see TML Weekly, March 28, 2015 - No. 13.

***

Material from Statistics

Canada generally does not attempt to analyze the data it provides from

a

viewpoint of what the Canadian economy requires to be sustainable and

meet

the needs of the people. This would require analyzing the underlying

contradictions in the relations of production, the way Canadians relate

to one

another in the economy. A human-centred analysis deals in particular

with the

existing class structure, where most Canadians sell their capacity to

work to

companies and state institutions. This social class relationship based

on private

ownership of the means of production is not in harmony with the broad

socialized nature of the forces of production. The actual producers who

constitute the vast majority of Canadians have no power over their

particular

part of the economy where they work or their workplace's relationship

with

the whole. They have no power to decide the direction of their part or

the

whole, or solve their problems. This dictatorship over Canadians within

the

economy is reflected in their disempowerment in politics where a cartel

system

of parliamentary dictatorship dominates the people.

Material from Statistics

Canada generally does not attempt to analyze the data it provides from

a

viewpoint of what the Canadian economy requires to be sustainable and

meet

the needs of the people. This would require analyzing the underlying

contradictions in the relations of production, the way Canadians relate

to one

another in the economy. A human-centred analysis deals in particular

with the

existing class structure, where most Canadians sell their capacity to

work to

companies and state institutions. This social class relationship based

on private

ownership of the means of production is not in harmony with the broad

socialized nature of the forces of production. The actual producers who

constitute the vast majority of Canadians have no power over their

particular

part of the economy where they work or their workplace's relationship

with

the whole. They have no power to decide the direction of their part or

the

whole, or solve their problems. This dictatorship over Canadians within

the

economy is reflected in their disempowerment in politics where a cartel

system

of parliamentary dictatorship dominates the people.

The closest attempt to an analysis in the following Statscan material comes in the conclusion but really is merely a description of problems and does not touch or expose the root contradictions. This observation is not a complaint but an indication of the lack of human-centred theory and the necessity to develop it. Statistics Canada is a state institution serving the monopoly capitalist class. The economists who work for Statscan are extremely professional and efficient in their field. Their work presents the surface of the economy and does not pretend to be anything more than a superficial representation. None of its economists are allowed to present an analysis that criticizes the current crisis-ridden direction of the economy or delve into the contradictions that must be resolved to open a path forward. Such an economist would come under severe criticism and be called upon to recant or be fired.

Human-centred theory does not drop from the skies or emerge spontaneously from descriptions of events or extensive data. Theory demands a conscious effort to analyze the concrete conditions from the point of view of what the economy needs to move forward to serve the people and resolve its contradictions. Theory requires the great human practice of abstracting absence or what founder and leader of CPC(M-L) Hardial Bains described as conscious participation of the individual in acts of finding out.

The importance of manufacturing for a modern economy cannot be overstated. The home economy requires means of production and articles of consumption without interruption. This can be accomplished only on a planned rational basis with all sectors participating in harmony within an internal exchange of value assisted by imports and exports but not dependent upon them. The internal exchange of manufacturing value with other sectors is needed to sustain the independent economy without the recurring crises of the current capital-centred direction where separately controlled and owned parts both compete and collude and have no allegiance to or great concern for the whole. The issue is not a lack of compassion on the part of private owners but the objective condition of competing with other privately owned parts at home and abroad and having ultimate concern for the particular part that is owned and no concern whatsoever for the actual producers who are summarily ridiculed and dismissed as a cost of production.

An independent economy serving the people requires a vigorous manufacturing sector in all regions of Canada producing sufficient value that can engage in continuous exchange with the public service sector, especially public education and health care, resource extraction, construction, material and social infrastructure (in particular social programs), culture, sports and all the other diverse aspects of a modern sustainable economy.

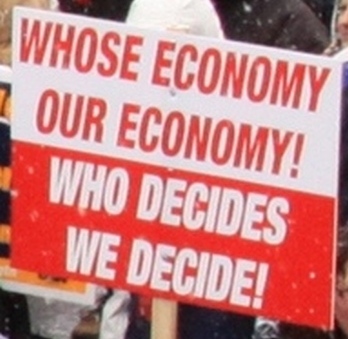

The key question facing not only theory but also the practical movement of the people in defence of their rights and for a way forward has become -- Who decides? The working class has reached a stage in history where it is called upon to lead all Canadians on all matters including the important one of the direction of the economy. The actual producers must step forward in a conscious organized way to provide the economy a new direction to solve its problems. Those who raise issues of private ownership of the means of production as an impediment to the working people taking their rightful leadership role must understand that without resolving the basic contradiction between private ownership of the parts of the economy and the socialized nature of the modern economy nothing can be sorted out. The people have the right to decide those matters that directly affect their lives. The current despotic authority that deprives the people of that right both in the economy and in politics must be deprived of its authority to do so.

Trends in Manufacturing Employment (Excerpts)

- André Bernard -

From 2004 to 2008, more than one in seven manufacturing jobs, nearly 322,000, disappeared [in Canada]. At the same time, job growth in other industries has been relatively strong. In fact, from 2004 to 2008, over 1.5 million jobs were created in the rest of the economy -- a growth of 11%. The national unemployment rate through 2007 and 2008 was also regularly among the lowest in the past 30 years. Manufacturing is clearly faring worse than the rest of the economy.

The Global Context

Canada is far from being the only country having to deal with a downturn in its manufacturing base. The United States, which continues to be Canada's largest trading partner, lost close to one-quarter (4.1 million) of its manufacturing jobs between 1998 and 2008.

The vast majority of other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries have also recorded major job losses in this industry in the past few years.

From 1990 to 2003, employment in manufacturing decreased by 29% in the United Kingdom, 24% in Japan, 20% in Belgium and Sweden, and 14% in France.

Ireland was the only country to experience impressive growth (25%). However, this growth was in the specific context of an influx of foreign investment and a service sector that grew even more rapidly than manufacturing. Mexico, Spain, and, to a lesser extent, Canada and New Zealand were the only other countries to increase manufacturing jobs from 1990 to 2003. The last available year for purposes of international comparisons being 2003, the result for Canada does reflect the significant job losses since 2004. The share of manufacturing in total employment has regressed persistently in almost all OECD member countries. This is not a recent trend. For example, in the early 1970s, more than one in five jobs in the United States were in manufacturing. In 2003, this proportion barely exceeded 11%. In the United Kingdom, over 30% of jobs in the early 1970s were in manufacturing. In 2003, this proportion dropped to 12%.

Over the long term, the proportion of service-sector jobs has increased while manufacturing's share has declined in almost all OECD countries. This phenomenon, if it can explain the long-term trends in the relative share of manufacturing jobs in total employment, does not explain the decline in the absolute number of manufacturing jobs.

As manufacturing activity has declined in relative importance in OECD countries, China has become the world centre of manufacturing employment. In fact, the number of workers in manufacturing in China was estimated at 109 million in 2002, which represents more than double the combined total (53 million) in all of the G-7 member countries.

Demographics (in particular the aging of the population observed in almost all developed countries) contribute to the increase in demand for services at the expense of manufactured products. In fact, the total final demand in numerous OECD countries shows a progressive decrease in the demand for manufactured products.

When productivity growth in manufacturing is greater than that in the services-producing sector, a reallocation of manufacturing jobs to the service sector can be expected. In the United States, for example, labour productivity growth in manufacturing was far greater than that in the entire non-agricultural economy since the 1970s, contributing to a decrease in the importance of the manufacturing industry in employment. Increased productivity means that a firm can produce the same quantity of goods with fewer workers, which can lead to job losses.

Variations in the [currency] exchange rate certainly have a significant impact on manufacturing in any country actively involved in international trade. Canada has experienced major fluctuations in its exchange rate for the last ten years with no general trend in appreciation or depreciation.

Trends in Canada

Chart A: After increasing in the late 1990s, manufacturing employment

stagnated and then declined.

Over the past ten years, the labour market

in manufacturing was marked by a period of great drive, slowdown, and a

significant decline. The recovery of the labour market in Canada since

the

mid-1990s first coincided with a boom in employment in manufacturing,

which

had been hit quite hard by the recession of 1991 to 1993. From 1998 to

2000,

growth in manufacturing employment was strong, peaking at 4.7% in 1999,

and was greater than growth in the rest of the economy for those three

years

(Chart A).

After recording very weak growth of 0.7% in 2004, employment in manufacturing experienced a clear downward trend with successive annual losses of at least 3% from 2005 to 2008. In these four years, more than one in seven manufacturing jobs were lost.

These losses resulted in the rapid erosion of the share

of manufacturing

jobs in the economy, from 14.9% in 1998 to 14.4% in 2004 before falling

sharply to 11.5% in 2008 (Chart B).

Chart B: Manufacturing's share of employment has fallen sharply since the turn of the century.

Job losses in manufacturing were compensated by major gains in the service sector and construction industry (Table 1). Accordingly, from 1998 to 2008, when the share of manufacturing jobs fell by 3.4 percentage points, the shares for services and construction increased by 2.5 and 2.0 points respectively, with 9 of the 15 service industries seeing their share increase.

| Table

1:

Jobs

by

industry,

share

of

total

employment |

1998 | 2001 | 2004 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||

| Goods sector | 26.0 | 25.3 | 25.0 | 23.5 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Utilities | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Construction | 5.2 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 7.2 |

| Manufacturing | 14.9 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 11.5 |

| Service sector | 74.0 | 74.7 | 75.0 | 76.5 |

| Wholesale trade | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Retail trade | 11.9 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 11.9 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Information and cultural industries | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Finance and insurance | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| Real estate, rental and leasing | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 6.1 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 7.0 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| Educational services | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.0 |

| Health care and social services | 10.2 | 10.3 | 10.9 | 11.1 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Accomodation and food services | 6.5 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Other services | 5.0 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Public administration | 5.6 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.4 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. | ||||

General Downturn in Manufacturing Since 2004

Almost all manufacturing industries have been in sharp decline since 2004. Of the 23 studied, only 6 showed job growth from 2004 to 2008, notably those pertaining to transportation equipment other than automobiles and automobile parts (9.2%), oil and coal products (8.5%), and computer and electronic products (7.4%). Conversely, 17 industries had job losses, often in high proportions (Table 2).

| Table

2:

Jobs

in

manufacturing

industries |

2008 | Change 1998 to 2004 | Change 2004 to 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | ||

| Textile mills | 9,600 | 3,400 | 20.7 | -10,200 | -51.5 |

| Clothing | 44,400 | -32,700 | -28.5 | -37,800 | -46.0 |

| Textile product mills | 14,700 | -14,700 | -37.1 | -10,200 | -41.0 |

| Wood products | 129,000 | 37,900 | 25.5 | -57,300 | -30.8 |

| Motor vehicle parts | 98,700 | 37,200 | 36.4 | -40,600 | -29.1 |

| Plastics and rubber products | 103,300 | 26,700 | 23.9 | -35,300 | -25.5 |

| Motor vehicles | 64,500 | 3,800 | 5.0 | -15,900 | -19.8 |

| Machinery | 112,300 | 35,100 | 33.9 | -26,200 | -18.9 |

| Furniture and related products | 103,600 | 32,100 | 33.9 | -23,100 | -18.2 |

| Miscellaneous | 85,600 | 12,900 | 14.3 | -17,800 | -17.2 |

| Primary metal | 77,400 | -15,100 | -14.0 | -15,000 | -16.2 |

| Paper | 90,600 | -17,900 | -14.7 | -13,200 | |

| Printing and related | 101,100 | 19,000 | 20.2 | -11,900 | -10.5 |

| Clay and refractory products | 59,000 | 14,800 | 29.4 | -6,200 | -9.5 |

| Chemicals | 109,800 | 9,300 | 8.6 | -7,800 | -6.6 |

| Food | 259,400 | 45,600 | 20.0 | -14,000 | -5.1 |

| Electrical equipment, appliances and components | 47,800 | -1,900 | -3.8 | -900 | -1.8 |

| Metal products | 177,500 | 17,500 | 11.0 | 1,500 | 0.9 |

| Beverage and tobacco products | 38,700 | -600 | -1.6 | 1,400 | 3.8 |

| Leather and allied products | 8,000 | -6,200 | -44.6 | 300 | 3.9 |

| Computer and electronic products | 109,500 | -3,300 | -3.1 | 7,500 | 7.4 |

| Petroleum and coal products | 19,100 | -1,000 | -5.4 | 1,500 | 8.5 |

| Transportation equipment (except motor vehicles and parts) | 106,700 | -2,900 | -2.9 | 9,000 | 9.2 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. | |||||

Textiles and clothing, which has long been one of the largest manufacturing employers in the country, was the hardest hit among the manufacturing industries. From 2004 to 2008, clothing manufacturers and textile and textile product mills saw almost half of their jobs disappear.

The Canadian automotive industry was also hard hit. Automotive parts manufacturing lost more than one-quarter of its employees from 2004 to 2008, while motor vehicle manufacturing lost one-fifth. Parts manufacturers saw their jobs go from 139,300 to 98,700, which completely cancelled the strong growth from 1998 to 2004. For their part, motor vehicle manufacturers lost 15,900 jobs between 2004 and 2008, following a rather modest job growth of 5.0% from 1998 to 2004. The Canadian automotive industry, concentrated mainly in Ontario, has been changing for several years. Vehicle production by the 'Big Three' U.S. automakers has been in sharp decline since 1998, while it has increased in Japanese-owned plants.

All industries related to wood and paper are beleaguered. Wood product manufacturers lost 57,300 jobs from 2004 to 2008, which more than negated all of the growth experienced from 1998 to 2004 (37,900 jobs). The entire lumber industry has experienced major challenges in these past few years, having to deal with the imposition of antidumping and countervailing duties by the United States from 2002 to 2006, the increase in energy and raw materials prices, the decrease in the demand for and price of lumber and the increase in the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar. The paper manufacturing industry has, for its part, been in a constant downturn for ten years, employment having declined successively by 14.7% from 1998 to 2004 and by 12.7% from 2004 to 2008. Mirroring the slump in the paper industry, the printing industry lost 10.5% of its jobs from 2004 to 2008.

Decline in Unionization in Manufacturing

Only a very small minority (4.1% in 2008) of manufacturing jobs are part-time and this proportion has remained virtually unchanged since 1998, which shows that proportionately as many full-time as part-time jobs were lost (Table 3). The very low proportion of part-time employment is an attribute peculiar to manufacturing -- over 20% of jobs in the rest of the economy are part time.

| Table

3:

Job

characteristics |

1998 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|

| % | ||

| Manufacturing sector | ||

| Full-time jobs | 96.0 | 95.9 |

| Part-time jobs | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| Company size | ||

| Less than 20 employees | 12.4 | 12.9 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 20.4 | 20.2 |

| 100 to 500 employees | 19.5 | 19.6 |

| More than 500 employees | 47.7 | 47.3 |

| Unionization rate | 32.2 | 26.4 |

| Average age (years) | 38.8 | 41.4 |

| Average years of seniority | 9.0 | 9.6 |

| Average earnings (current $) | 15.6 | 20.8 |

| % | ||

| Rest of the economy | ||

| Full-time jobs | 78.6 | 79.7 |

| Part-time jobs | 21.4 | 20.3 |

| Company size | ||

| Less than 20 employees | 23.7 | 20.3 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 15.8 | 15.4 |

| 100 to 500 employees | 15.1 | 13.4 |

| More than 500 employees | 45.4 | 50.9 |

| Unionization rate | 30.1 | 29.5 |

| Average age (years) | 38.3 | 39.9 |

| Average years of seniority | 7.9 | 8.0 |

| Average earnings (current $) | 12.6 | 17.7 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. | ||

Unionization is generally seen, among other things, as an indicator of job quality. Unionized jobs typically benefit from a wage premium, even when employee and workplace attributes are taken into consideration. From 1998 to 2008, unionized jobs in manufacturing disappeared twice as quickly as non-unionized ones. Consequently, the rate of unionization decreased from 32.2% to 26.4%. For the rest of the economy, unionization declined less, from 30.1% to 29.5%.

The distribution of manufacturing jobs according to firm size has also not experienced notable change in the past ten years, which means that job losses did not hit small businesses harder than large businesses.

Central Canada Hit Harder

Quebec and Ontario make up

Canada's industrial core. Outside these two provinces, there are

generally

proportionately fewer manufacturing jobs. In 2008, manufacturing jobs

in

Quebec and Ontario represented 14.0% and 13.5% of jobs, respectively,

whereas the national average was 11.5% (Table 4). Together, these two

provinces account for more than 1.4 million (73.3%) of the

manufacturing jobs

in Canada. Manitoba also has a significant manufacturing presence, with

11.3%

of its jobs depending on it. The proportions for all the other

provinces are

below the national average. Saskatchewan, which is more natural

resources-oriented, is the province with the fewest jobs in

manufacturing (6.0%).

| Table 4: Changes in jobs by province | Change 1998 to 2004 | Change 2004 to 2008 | Manufacturing jobs in 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | number | % of total employment | |

| Manufacturing | 198,600 | 9.5 | -321,800 | -14.0 | 1,970,300 | 11.5 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,400 | 8.9 | -3,100 | -18.0 | 14,100 | 6.4 |

| Prince Edward Island | 800 | 14.8 | -100 | -1.6 | 6,100 | 8.7 |

| Nova Scotia | 2,600 | 6.3 | -4,500 | -10.3 | 39,100 | 8.6 |

| New Brunswick | 5,300 | 14.5 | -6,700 | -16.0 | 35,200 | 9.6 |

| Quebec | 30,200 | 5.0 | -86,700 | -13.8 | 543,600 | 14.0 |

| Ontario | 119,200 | 12.2 | -198,600 | -18.1 | 901,200 | 13.5 |

| Manitoba | 6,000 | 9.5 | -200 | -0.3 | 68,700 | 11.3 |

| Sasktachewan | -400 | -1.4 | 2,100 | 7.3 | 30,900 | 6.0 |

| Alberta | 18,400 | 14.6 | -300 | -0.2 | 144,100 | 7.2 |

| British Columbia | 15,300 | 7.8 | -23,800 | -11.3 | 187,400 | 8.1 |

| Rest of the economy | 1,702,100 | 14.2 | 1,500,700 | 11.0 | 15,155,600 | 88.5 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 20,500 | 11.6 | 9,100 | 4.6 | 206,200 | 93.6 |

| Prince Edward Island | 6,500 | 12.0 | 3,500 | 5.8 | 64,200 | 91.3 |

| Nova Scotia | 44,300 | 12.5 | 15,500 | 3.9 | 414,100 | 91.4 |

| New Brunswick | 29,500 | 10.6 | 22,800 | 7.4 | 331,000 | 90.4 |

| Quebec | 392,800 | 14.8 | 287,900 | 9.4 | 3,338,100 | 86.0 |

| Ontario | 744,000 | 16.6 | 569,400 | 10.9 | 5,786,100 | 86.5 |

| Manitoba | 36,400 | 7.7 | 30,300 | 6.0 | 538,000 | 88.7 |

| Sasktachewan | 9,600 | 2.2 | 30,900 | 6.9 | 481,800 | 94.0 |

| Alberta | 229,200 | 16.6 | 256,100 | 15.9 | 1,869,200 | 92.8 |

| British Columbia | 189,000 | 11.4 | 275,400 | 14.9 | 2,126,900 | 91.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. | ||||||

In six provinces, at least one in ten manufacturing jobs were lost from 2004 to 2008. The largest drop was in Ontario, where 198,600 jobs, almost one in five (18.1%), disappeared in only four years. Significant drops were also seen in Newfoundland and Labrador (-18.0%), New Brunswick (-16.0%), Quebec (-13.8%), British Columbia (-11.3%) and Nova Scotia (-10.3%).

Do Small Urban Areas Have More Difficulty Dealing with Job Losses?

From 2004 to 2008, very large CMAs (very large Census Metropolitan Areas -- Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver) lost the most manufacturing jobs proportionally. More than 150,000 jobs were lost in one of these three very large CMAs, a collective drop of 17.2% (Table 5).

| Table 5: Change in jobs by type of region | 2008 | Change 1998 to 2004 | Change 2004 to 2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| '000 | % | '000 | % | ||

| Manufacturing | 1,970.3 | 198.6 | 9.5 | -321.8 | -14.0 |

| Montréal-Toronto-Vancouver | 742.4 | 69.2 | 8.4 | -154.2 | -17.2 |

| Large census metropolitan areas | 273.8 | 30.8 | 11.5 | -23.9 | -8.0 |

| Small census metropolitan areas | 267.4 | 16.0 | 5.4 | -46.5 | -14.8 |

| Small towns and rural areas | 691.7 | 82.6 | 11.8 | -92.3 | -11.8 |

| Rest of the economy | 15,155.6 | 1,702.1 | 14.2 | 1,500.7 | 11.0 |

| Montréal-Toronto-Vancouver | 5,323.8 | 706.5 | 17.5 | 581.1 | 12.3 |

| Large census metropolitan areas | 2,885.1 | 367.7 | 16.7 | 309.8 | 12.0 |

| Small census metropolitan areas | 2,124.9 | 233.4 | 13.7 | 182.5 | 9.4 |

| Small towns and rural areas | 4,827.2 | 394.5 | 9.9 | 432.9 | 9.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. | |||||

In smaller regions (large CMAs -- Québec, Ottawa-Gatineau, Hamilton, Winnipeg, Calgary and Edmonton), the drops were not as large, but were significant nonetheless.

In small CMAs (a population between 100,000 and 500,000) and in small towns and rural areas (fewer than 100,000 inhabitants and rural areas) manufacturing jobs decreased by 14.8% and 11.8% respectively.

Although small towns and rural areas lost fewer jobs proportionally, the rest of their economy also progressed more slowly. Total employment growth from 2004 to 2008 was 7.6% in very large CMAs, compared with 6.6% in small towns and rural areas.

On average, for each manufacturing job lost in very large cities between 2004 and 2008, 3.8 jobs were created in other industries. In small towns and rural areas, for each manufacturing job lost, 4.7 jobs were created elsewhere.

However, the pool of non-manufacturing jobs is generally

lower paying in

small towns and rural areas than in very large CMAs. In small towns and

rural

areas, wages and salaries in manufacturing are on average 25.3% higher

than

in non-manufacturing, compared with a difference of 11.2% in very large

CMAs (Table 6).

| Table 6: Job characteristics by type of region | Unionization | SME1 | Average age | Average seniority | Average hourly earnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | years | $ | |||

| Manufacturing sector | |||||

| Montréal-Toronto-Vancouver (ref.) | 21.7 | 58.6 | 41.9 | 8.7 | 20.09 |

| Large census metropolitan areas | 20.8 | 51.1* | 40.6* | 8.8 | 22.87* |

| Small census metropolitan areas | 30.8* | 44.5* | 41.1* | 10.5* | 22.76* |

| Small towns and rural areas | 32.4* | 50.5* | 41.0* | 10.4* | 19.78* |

| Rest of the economy | |||||

| Montréal-Toronto-Vancouver (ref.) | 27.0 | 48.6 | 39.9 | 7.6 | 18.06 |

| Large census metropolitan areas | 30.6* | 42.7* | 39.0* | 7.4 | 19.93* |

| Small census metropolitan areas | 31.9* | 45.6* | 39.4* | 8.2* | 17.82* |

| Small towns and rural areas | 30.4* | 55.9* | 40.7* | 8.6* | 15.79* |

| * significantly

different from the reference group (ref.) at the 0.05 level 1. A small or medium-sized enterprise is defined as a business with less than 500 employees. Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, 2008. |

|||||

Manufacturing Output and Productivity

Chart C: While overall GDP grew from 2005 to 2008, manufacturing output declined since 2006. |

Examining the

evolution of industrial production, measured by gross domestic product

(GDP),

provides a different perspective than employment data. Industrial

production

was in a slump from 2004 to 2007, and dropped 3.7% in the first two

quarters

of 2008 (Chart C). Each year, industrial production increased less than

the

total overall production. However, production generally decreased less

than

employment, meaning that some of the job losses can be attributed to

increased

productivity in manufacturing industries. In 3 out of 4 years from 2004

to

2007, and 7 out of 10 years from 1998 to 2007, labour productivity

increased

more quickly for manufacturing industries than for the economy as a

whole.

In other words, while production was decreasing, businesses were also

becoming more efficient and could produce more with the same workforce.

This trend of labour productivity increasing more quickly in

manufacturing is

neither new nor specific to Canada. In fact, manufacturing generally

contributes greatly to overall productivity growth in most OECD

countries.

Conclusion

From 2004 to 2008, more than one in seven manufacturing jobs (322,000) disappeared in Canada. The majority came from Ontario, but drops were also evident in other parts on the country. In six provinces, at least 1 in 10 manufacturing jobs disappeared from 2004 to 2008. These losses occurred during a period of economic turbulence in the country as the exchange rate fluctuated widely.

These trends are not unique to Canada -- manufacturing has been declining in most OECD countries. The situation in Canada was noticeable for being somewhat delayed, with manufacturing jobs beginning to decline only in 2004, while other countries, notably the United States, had already registered significant job losses for several years.

The employment decline has affected almost all manufacturing industries. However, textiles, clothing, and motor vehicle and automotive parts, as well as industries related to wood and paper, were hit hardest. The jobs lost were more likely to be unionized jobs.

Read The Marxist-Leninist Daily

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca