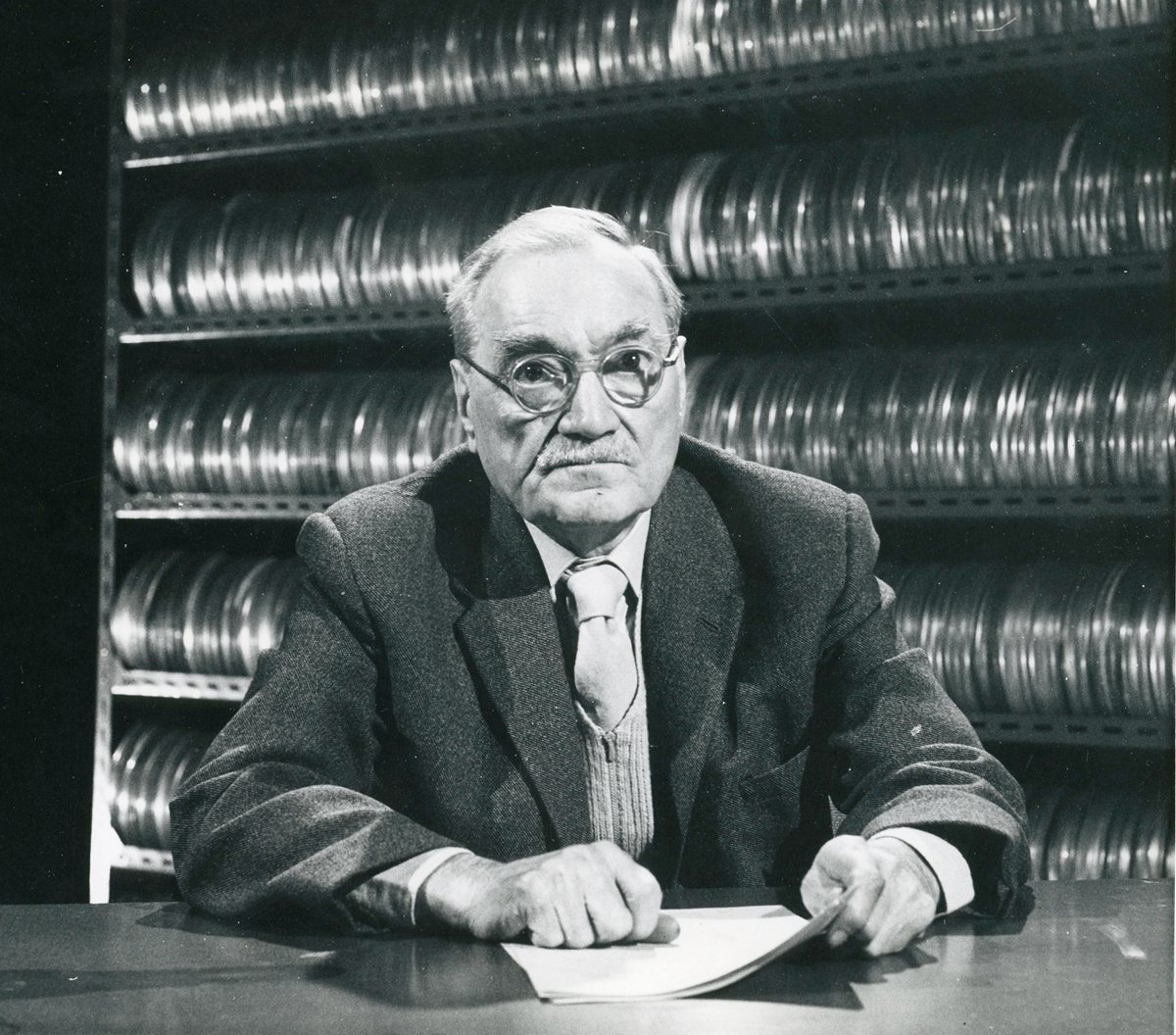

John Grierson, Father of the Documentary Film

John Grierson, considered the father of the documentary film, was the first Commissioner of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and wrote the bill that went before Parliament creating the then National Film Commission in 1939.

John Grierson, considered the father of the documentary film, was the first Commissioner of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) and wrote the bill that went before Parliament creating the then National Film Commission in 1939.

By 1939, when he arrived in Canada, Grierson was a well-known filmmaker and considered the founder of the British documentary movement. It was John Grierson who coined the phrase ‘the documentary film.’

The French had been using the word documentary to describe travel or exploratory films. Grierson said, “Documentary is the creative interpretation of actuality.”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King was in favour of developing Canadian film and supported the founding of this new board and the invitation to bring Grierson to Canada.

The National Film Board of Canada was born.

As a teenager Grierson went to Glasgow and participated in the workers’ movement there that was dubbed “Red Clydeside.” Many mass struggles took place between 1910 and the 1930’s including a massive rally of 90,000 people in January 31, 1919 with the red flag being raised in the centre of the crowd.

January 31, 1919 rally in Glasgow raises the red flag

Fearing a revolution like the one the Bolsheviks had led in Russia the state sent in the army, including tanks, to quell the demonstration.

In Roger Blais’ 1973 documentary film Grierson, we hear him saying, “I was on a soapbox at the age of sixteen and made unemployable and put on the blacklist for making a speech at the age of seventeen.”

His mother was a socialist and a suffragette and John joined the Fabian Society in his first year of university.

In 1923 he graduated from the University of Glasgow with a Masters degree in English and philosophy.

That same year, Grierson received a Rockefeller Research Fellowship to study in the United States at the University of Chicago, and later at Columbia and the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His research focus was the psychology of propaganda — the impact of the press, film, and other mass media on forming public opinion.

He then went to Hollywood and was excited by the tremendous technical development of film and appreciated that, “they populated the arts with common people.”

Grierson was also excited by the work of the great Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein who, he said, “Reacted to all the forces of the time, the great new industrial world, the colossal new technological developments. Eisenstein wanted the cinema in its power over movement to reflect the movement of these great masses of industrial forces.”

In Gary Evans’ book John Grierson: Trailblazer of Documentary Film we read that at the Coffee House Club in New York Grierson was praising Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin saying, “If a film has visual rhythm in presenting objective social reality, it achieves psychological connection.” A club member listening protested, saying Eisenstein’s film was communist subversion and to this Grierson answered, “Open your eyes and see its greatest moment, the Odessa steps sequence. Three hundred non-actors choreographed to create a vast movement, a building of tempo. See the violent use of editing for smash effects and symbolic counterpoint.

“Eisenstein was first to make it plain that film could be an adult and positive illuminating force in the world. The Russians have learned to use art as a hammer. They are far ahead of the West.”

Evans’ book says it was that day at the Coffee House Club that he met Robert J. Flaherty, a filmmaker who was to become a lifetime friend and colleague.

Fascinated by what Flaherty had done in his 1922 Canadian film Nanook of the North and intrigued with the idea of applying Flaherty’s technique to the common people of Scotland Grierson made his first film, Drifters (1929).

Still from Grierson’s first documentary film, Drifters. |

Grierson told Flaherty, “I liked the poetry of your exploratory style and the way its tempo spelled out a drama that resides in living fact.”

This silent film depicted the harsh life of herring fishermen in the North Sea and it revolutionized the portrayal of working people. It premiered in a private film club in London in November 1929 on a double-bill with Eisenstein’s film The Battleship Potemkin (which was banned from general release in Britain until 1954).

“I got to put the working class on the screen for the first time in England”, he says in his own 1968 documentary film I Remember, I Remember. “It took all that time to get a working man on the screen other than a comic figure.”

Working as a film officer for the British government he led a government department training a stable of energetic young filmmakers. Irving Jacoby, author and filmmaker, says in Grierson that Grierson brought around him young intellectuals “all in rebellion, all looking for some way to change things, to strike back, to make something happen … artists in the best sense of the word.”

Those young men included Basil Wright, Edgar Anstey, Stuart Legg, Paul Rotha, Arthur Elton, Humphrey Jennings, Harry Watt, and Alberto Cavalcanti. This group formed the core of what was to become known as the British Documentary Movement.

Some of these new documentary filmmakers appear in Blais’ film and recollect that time. Paul Rotha says, “He gave up the wonderful pleasure of directing a film … so that he would make more of a contribution by leading a group of filmmakers and educating them, than making one film of his own at a time.”

Sir Arthur Elton says Grierson, “… turned me on to make a film about airplane engines … men doing various jobs in the fitting shops … When we came to show the rough cut of the film to the officials at the Air Ministry they were really offended at the close, intimate treatment of the workers in the foundry and asked if we could take the close-ups out. I think they felt that their middle-class privilege had been invaded.”

“Hard to understand today, but we were putting the British working man onto the screen and before that he was the comic relief in these ghastly British films where there was always a funny gardener or a funny taxi driver. We knocked all that down and for that the establishment looked on us as subversive,” said Harry Watt.

Edgar Anstey says about Grierson, “He was not anxious or eager to draw conclusions from the films but felt that if you could give people the facts and then guide them, perhaps, a little in the direction of the right conclusion then you would have a socially valuable outcome. It really was an advanced form of social education.”

And Basil Wright, “… we invented cinéma vérité by putting the camera in front of people living in destitute conditions and got them to tell their stories.”

During this time Grierson’s department produced a series of groundbreaking films, including Night Mail, Coal Face, The Song of Ceylon and The Private Life of Gannets which went on to pick up an Academy Award in 1937. The group worked with Benjamin Britten, the composer, and W. H. Auden, the poet, incorporating their work into the films in a way that hadn’t been seen before.

Still from documentary film, Night Mail. |

Canadian diplomat Ross McLean invited Grierson in 1938 to counsel the Canadian Government on the use of film. McLean, successor to Grierson as NFB Commissioner says in Grierson, “Prime Minister Mackenzie King was a great film fan and the main support of the National Film Board during the war.”

“… Ottawa invited Grierson to Canada in June 1938 to survey government film activity,” writes Gary Evans.

Grierson in I Remember, I Remember states, “The Film Board was a deliberate creation to do deliberate work. To bring Canada alive to itself and to the rest of the world. It was there to declare the excellence of Canada to Canadians and to the rest of the world. It was there to invoke the strengths of Canada, the imagination of Canadians in respect of creating their present and their future.”

“The people I brought in had the common bug of being very Canadian and being aware of it and who weren’t going to put up with any more nonsense from the English raj.”

The renowned Norman McLaren started working with Grierson in 1935 when he was offered a job with the General Post Office Film Unit in London. In 1941 Grierson invited him to join in the work with the NFB and gave him free rein.

Over the course of his career, McLaren mostly created experimental animation, with music and dance as important elements. His films have garnered more than 200 awards. Neighbours won an Oscar in 1952, and Blinkity Blank received the Palme d’Or for short films at the 1955 Cannes festival.

Canada Carries On was a series of short films made by the National Film Board of Canada which ran from 1940 to 1959. The series was initially created as morale-boosting propaganda films during the Second World War. That series and another famous series that began in 1942, The World in Action, appeared each month in 800 Canadian theatres, reaching 4 million viewers. The World in Action reached millions more in the U.S., screening in over 6,500 theatres.

The series was initially produced by Stuart Legg and he wrote and directed most of the episodes. One of the most famous films from this series was his Churchill’s Island, released in Canada in June 1941 and winner of the first Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject).

The narrator for many of these films was Lorne Greene, a great Canadian actor known for his work on radio broadcasts as a news announcer at CBC. His sonorous recitation led to his nickname, “The Voice of Canada,” and, when reading grim battle statistics, “The Voice of Doom.”

Grierson, left, as Chair of Canada’s Wartime Information Board meets with the Head of Graphics at the NFB, Ralph Foster. |

At that time, 1942, Grierson was also director of Canada’s Wartime Information Board.

In Gray’s other book, John Grierson and the National Film Board, he writes about the films that were made highlighting and supporting Canada’s ally, the Soviet Union, including Inside Fighting Russia and Look to the North. In the 1944 film Our Northern Neighbour the narrator states, “And now, with the Red Armies’ offensive everywhere approaching their titanic climax, the western democracies are realizing that the effectiveness of the peace will greatly depend on how well they grasp the viewpoint of the Kremlin.”

Evans writes, “… women became the backbone of the organization, serving as stock shot researchers, editors, writers and administrators. Many of the Board’s films during the war featured women and gave recognition to their work and life. Titles include The Home Front, Proudly She Marches, Women Are Warriors, Inside Fighting Canada.

Grierson’s wife Margaret was an editor and they met in England when she came to edit his film. She worked alongside and supported John through his whole life’s work. Their house was always open to the young upcoming filmmakers and Margaret created a welcoming atmosphere providing food and drink to all.

Even though the Canadian, British and U.S. Allies knew about the Nazi concentration camps the government wouldn’t let the NFB speak of it. In the book John Grierson we read, “Keep this under your hat,” Grierson told Arthur Gottlieb, “The Cabinet War Committee declared Canada’s information policy on this issue: remain silent.”

After the Second World war the United States, Great Britain, Canada and other countries launched a big anti-communist campaign against the Soviet Union and communists in their countries. The ‘Gouzenko affair’ was one such action. That featured a man named Igor Gouzenko, a clerk in the Soviet embassy in Ottawa who defected, alleging to have secret documents.

Grierson was brought before a secret tribunal and questioned about his one-time secretary who was said to be connected to the “spy ring.” The investigators then threw doubt on Grierson himself for his alleged “communist” sympathies.

Grierson left the National Film Board. Years later when all the government documents pertaining to this ‘Gouzenko affair’ became available it was found that there were no secret documents and no spy ring and the whole affair was an RCMP and FBI concoction and part of the anti-communist witch hunt.

In 1949 Ottawa censored the NFB film The People Between for being pro-communist in its recognition of the People’s Republic of China and in 1950 the government, claiming ‘communist employees’ at the NFB, installed a new Commissioner who had no ties to Grierson.

Grierson’s emphasis on realism had a profound long-term influence on Canadian film. “Art is not a mirror,” he said, “but a hammer. It is a weapon in our hands to see and say what is good and right and beautiful.”

By 1945 the NFB had grown into one of the world’s largest film studios and was a model for similar institutions around the world. The people Grierson brought in during the war became the core of artists who made films for many years to come.

With no job he went to New York looking for work, only to find the FBI were following him and tapping his phone. We see in Grierson the film critic Bosley Crowther recounting the story of how he went to meet Grierson in a New York hotel and Grierson said to him, “Come on in this room – not the other room. We’ll have to talk very low as I’m being bugged.”

The United States lifted his work permit and he was forced to leave. He returned to Great Britain.

He joined UNESCO for a year in Paris, then worked for the Central Office of Information in London, became an Executive Producer at Group 3 – an experimental film company – and for ten years hosted This Wonderful World on Scottish television.

From Grierson we hear, commenting on Grierson’s time hosting This Wonderful World, filmmaker Laurence Henson: “He would try and introduce a film on Reubens where he would show a piece of World Cup football and explain Reubens to a Glaswegian audience and explain how Reubens played the rectangle of the canvas in the way a football team played the rectangle of the corners of the green of the football field.”

Grierson was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. He was a member of the Vancouver Film Festival jury as well as a member of the juries in Belgrade and Venice, an advisor to the Films of Scotland Committee and a recipient of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts Medal. He was invited to the NFB’s twenty-fifth anniversary held in Montreal.

McGill University, in 1969, offered him a job and his classes began with just eight students, but as word spread that number grew to 800. He was now inspiring another generation of filmmakers, making it three generations of filmmakers influenced by Grierson.

John Grierson made a great contribution to world cinema. The National Film Board that he created and led has won more than 5,000 awards. That includes 12 Oscars, including a 1989 Honorary Academy Award for overall excellence in cinema. It has amassed more Academy Award nominations than any other film organization based outside of Hollywood.

“Grierson has the genius to identify what they were doing and to organize the system in which to develop the thought to satisfy those needs. So, that’s the reason why Grierson is a great model for me. He was open; he was very, very open. You know, he was a man of stature but he was not there imposing himself, he was there full of curiosity. Searching for new things. And that’s the reason why the dialogue was very easy between us,” says the Italian film director Roberto Rossellini, ‘The Father of Neorealism’, in Grierson.

In I Remember, I Remember, we see and hear Grierson saying, “I want the real professional communicators to be the teachers. … the one most important thing in this world is: who chooses the teachers? Who chooses the teachers of the teachers?”

John Grierson is like many others – Paul Robeson, Marie Dressler, Muhammed Ali – who, after being stripped of their livelihood and defamed are later awarded and praised.

John Grierson was born in Stirling, Scotland in 1898 and died at Bath, England in 1972.

|

|