June 28, 2021 - No. 62

Workers' Forum

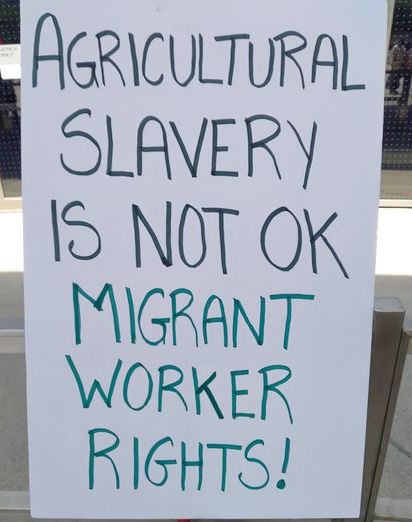

congratulates all the workers and advocacy organizations such as

Migrant Rights Network and Migrante Canada who held successful actions

across Canada on the occasion of June 20, World Refugee Day, to once

again give voice to Canadians' demand for Status for All! -- for

refugees, students,

migrant workers and undocumented people. It is clear that it is thanks

to the workers who speak out and organize for the affirmation of the

rights of all that the truth of what happens in Canada becomes known

and together we can advance the fight for the rights of all.

Workers' Forum deeply

appreciates the stand taken by Migrante Canada that the call for full

and permanent immigration status is a call for an end to a system of

deadly racialized exclusion from rights, protections and dignity; that

the fight in defence of the rights of migrant workers is not simply a

fight to demand rights under

Canadian laws based on colonialism but a challenge to the violent and

unfair nature of this whole system; that we must join together and

demand that Canadian laws and policies do not force more people out of

their homes anywhere.

Workers' Forum deeply

appreciates the stand taken by Migrante Canada that the call for full

and permanent immigration status is a call for an end to a system of

deadly racialized exclusion from rights, protections and dignity; that

the fight in defence of the rights of migrant workers is not simply a

fight to demand rights under

Canadian laws based on colonialism but a challenge to the violent and

unfair nature of this whole system; that we must join together and

demand that Canadian laws and policies do not force more people out of

their homes anywhere.

According to the United Nations World Migration Report 2020, there

were approximately 25.9 million refugees globally as of 2018.

Palestinians registered with United Nations Relief organizations

accounted for 5.5 million of that total. While 25.9 million is a large

number, it is less than 10 per cent of the estimated 272 million

international

migrants in the world in 2019. Out of a global population of 7.7

billion, it means one in every 30 people on earth is an international

migrant. Economic insecurity is the leading reason for people leave

their homes, in search of employment and stability. War, violence and

oppression is second to economic insecurity. This phenomenon of

hundreds

of millions compelled to become international migrants is clearly an

expression of a global social order that rains catastrophe down upon

the peoples of the world. This is the creation, out of economic

insecurity, war, violence and oppression, of a pool of workers to be

superexploited, and that superexploitation is cruelly being called

"mobility of

labour" which is considered a Charter Right in Canada and a fundamental

human right.

These

are living breathing human beings, with legitimate claims upon society

to affirm and guarantee their rights wherever they are, not just where

they were born. This situation is also the face of a new world in the

making, which is coming into being, of the workers of all lands who,

regardless of place of origin, exist as one working class in

whichever country they are living. Migrants, regardless of the status

imposed upon them, are part and parcel of the main force for humanizing

the social and natural environment. They are "essential workers" as we

have seen in Canada during the pandemic. It is in laying claim to that

which belongs to them by virtue of being human and advancing

the fight for the rights of all that societies will come into being

which uphold the rights of all.

These

are living breathing human beings, with legitimate claims upon society

to affirm and guarantee their rights wherever they are, not just where

they were born. This situation is also the face of a new world in the

making, which is coming into being, of the workers of all lands who,

regardless of place of origin, exist as one working class in

whichever country they are living. Migrants, regardless of the status

imposed upon them, are part and parcel of the main force for humanizing

the social and natural environment. They are "essential workers" as we

have seen in Canada during the pandemic. It is in laying claim to that

which belongs to them by virtue of being human and advancing

the fight for the rights of all that societies will come into being

which uphold the rights of all.

In Canada, internal migration is also a significant problem. More

and more, workers are forced to leave their homes to find work elsewhere in

the country because their industrial and service sectors, their local

and regional economies have been wrecked by global narrow private

interests. We have to step up our work also on this important

issue.

We are one working class, one humanity, waging one struggle for the

rights of all and for a human-centred system everywhere that upholds

the rights and dignity of all human beings!

Sudbury, June 20, 2021

Living quarters at an oil sands work camp

North of Fort McMurray. (Narwhal)

Alberta has the largest fluctuations in internal migration from one

province to another of any province or region, with people moving to

Alberta during boom times and leaving the province when oil prices

crash. Statistics Canada reports, "Since comparable data was available

beginning in 1971/1972, Alberta and

British Columbia have been the two primary recipients of net

interprovincial migration in Canada. From 1971/1972 to 2015/2016,

Alberta has gained 626,375 net interprovincial migrants, while British

Columbia added 602,233 migrants."[1]

Internal

migration to Alberta is strongly related to the need for workers in the

oil sands and other oil and gas projects. Workers came from all over

Canada and around the world as bitumen extraction grew 376 per cent

from 2000 to 2018, creating a construction boom. Many came from the

regions where the rip and ship forestry was in crisis.

From 2004 to 2008 alone, the number of workers from other parts of

Canada grew from 67,500 workers to 133,000. By comparison,

approximately 59,500 Albertans drew a portion of their income from

outside of the province in 2008 -- most often in British Columbia,

Ontario and Saskatchewan.[2]

At present, more people are leaving Alberta than coming to Alberta

from other parts of Canada. Even though production continues to

increase, there are fewer jobs in the oil sands in both construction

and extraction. But workers continue to "commute" to work in the oil

sands as "rotational work" has become a permanent feature, not only for

construction and periodic maintenance, but for year-round work in

extraction and processing. Working on the oil rigs in conventional oil

extraction has also always been rotational but seldom involved workers

traveling from out of province or long distances. A "rotational worker"

is defined as a worker who does not return to his or her permanent home at

the end of each day's work.

From 2000 to 2014, the mobile labour force in the Regional

Municipality of Wood Buffalo grew nearly ten-fold to more than 50,000

rotational workers housed in more than 100 camps established anywhere

from 20 to 100 or more kilometers from the nearest population centre,

with some clustered around a nearby airstrip. While these numbers

have decreased since the downturn in oil that began in late 2014, a

fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) workforce many thousands strong remains core to

the sustained operations and maintenance of established oil sands

facilities.[3]

While many workers in the oil sands live in Fort McMurray as their

permanent home, there are a large number whose permanent homes are far

from the oil sands. Workers come from as far as 5,000 kilometers away.

Those working close to Fort McMurray have temporary accommodation in Fort

McMurray, but the majority live in work camps.

Together, these workers are referred to as the "shadow population" of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo.

The Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo includes the

"shadow population" in its municipal census, defined as people who live

in the municipality for at least 30 days a year, but have a permanent

home elsewhere. According to the 2018 census, there are 75,000

permanent residents in Fort McMurray, and a "shadow population" of

36,678 in Fort McMurray, of whom 32,855 lived in work camps. Fort

McMurray's population declined by 10 per cent from 2015, following the

wildfire in 2016 that destroyed thousands of homes. The "shadow

population" has also declined by about 15 per cent since 2015 following

the oil price crash. Those not living in work camps may live in

hotels or motels, RVs or campers, rent a room or apartment in Fort

McMurray, or even couch surf. The census is a snapshot in time, but

does not identify how many workers actually come and go during the year.

A study conducted by PetroLMI in 2015 surveyed 12 oil sands

companies with 26,874 employees. Ten of the twelve companies had

rotational work arrangements, and the majority expected the rotational

workforce to increase. In-situ extraction (where the bitumen is deep in

the earth) is the fastest growing sector of the oil sands and is

heavily

reliant on rotational workers.

Most of the in-situ projects as well as newer mines are more than an

hour's drive from the outskirts of Fort McMurray, and some are quite

remote. There are estimated to be 100 or more work camps, which house

from 20 to 1,500 workers each. The workers who cook and work in the

kitchens, clean and maintain the camps also work on

rotation, often with very long shifts. The Mayor and town

council have called for many years for sufficient resources to provide

services to this "shadow population," a demand ignored by the

provincial government.

It is estimated that about 15,000 workers work in fly-in, fly-out

projects. Most projects have their own private aerodromes owned by one

or more monopolies, or workers fly to and from the Fort McMurray

regional airport. A study conducted by a consortium of companies

operating in the oil sands found that about two thirds of these workers

live in Alberta, with five per cent in the Wood Buffalo region, and the

rest mainly in Edmonton (25 per cent) and Calgary (22 per cent),

followed by British Columbia (13 per cent), the Atlantic provinces (nine

per cent), and Saskatchewan (five per cent), and a small number from

Quebec, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories.

As many as 10,000 workers are involved in the annual scheduled

maintenance known as shutdowns or turnarounds, many from out of

province. The turnarounds require many trades, including pipefitters,

boilermakers, carpenters (scaffolders), heavy equipment operators,

insulators, and labourers. Work at one site usually lasts for about 45

days,

and workers may work more than one turnaround. Shifts in 2021 were as

long as 24 days with no days off. This year the turnaround at CNRL saw

the largest workplace outbreak of COVID-19 in North America, with more

than 1400 workers becoming infected, and tragically, two deaths.

Notes

1. Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada - Internal Migration: Overview, 2015/2016, Statistics Canada

2. Statistics Canada, 2011 National Household Survey, Catalogue no. 99-012-X2011033

3. Nichols, Applied Management, 2018; Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, 2018.