|

December 3, 2020 - No. 82

California Proposition 22

Lessons to Be Learned on How

Super Exploitation of Gig Workers

Is Made Legal

- Workers' Centre of

CPC(M-L) -

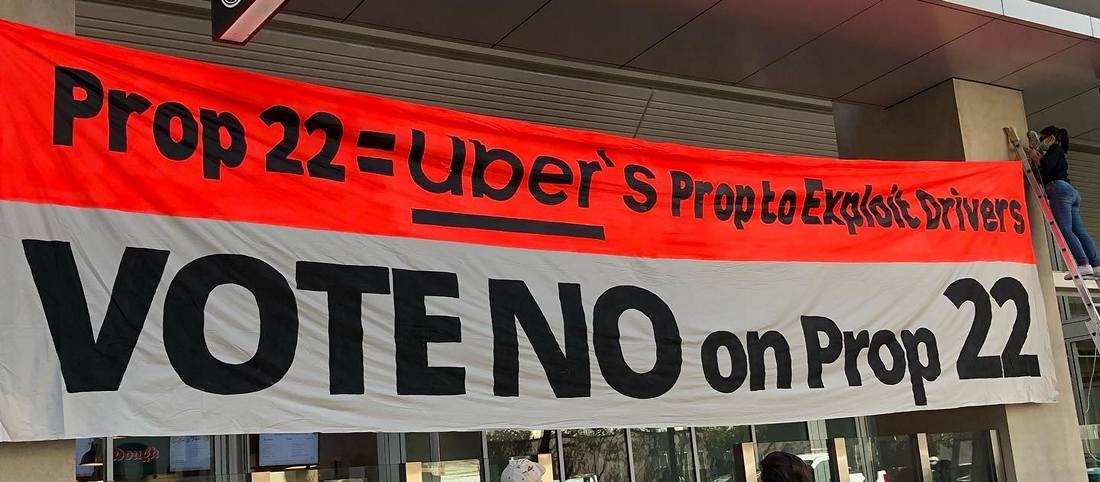

November 4, 2020. Demonstration by gig workers

against Proposition 22. (B. Anderson)

• Imperialist Democracy on

Ugly Display in California

• Corrupt Electoral Process

to Ensure Government of Powerful Private

Interests

• What It Means to

Legally Deny Network Workers Their Status as

Workers - K.C. Adams

• The Case for Voting

"No" on CA Prop 22 (Excerpts)

• Most Ride-Hailing

and Delivery Workers in San Francisco Not

Eligible to Vote

California Proposition 22

The Workers' Centre of the Communist Party of

Canada (Marxist-Leninist) is devoting this issue

of Workers' Forum

entirely to how the network companies, Uber,

Lyft, Instacart, Postmates

and DoorDash, have acted in California to

legally deny

network workers their status as workers. They

did this using

"Proposition 22," which passed November 3. The

aim of Proposition 22 is

to give the network companies the legal

authority to get away with

super-exploiting network workers with impunity.

The network companies

operate internationally and they have combined

forces in cartels and

coalitions to push their narrow private

interests, including their

refusal to provide even a minimum wage or

compensate their drivers for

work done. Based on their achievement in

California, they have now made

it clear that they expect to extend these

efforts. "Going forward,

you'll see us more loudly advocate for new laws

like Prop 22,"

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi declared.

Drivers for network companies, also referred to

as gig workers, are already a super-exploited

section of the working class. They have been

organizing for several years in many countries,

including Canada, to defend their rights.

Actions included strikes against Uber and Lyft

on March 25, 2019. In May of that year, drivers

organized collectively and held a day of action

with strikes against Uber in at least 10 U.S.

cities and on five continents.

In California, in particular, drivers have

formed their own organizations, such as

Rideshare Drivers United (RDU). RDU was a main

force in the 2019 actions and has grown to about

19,000 members. Individuals have taken

initiative to join with others to create their

own networks and Facebook pages to communicate

with each other and assist in solving problems

and countering the companies' unjust actions

against them. One San Francisco driver, for

example, developed a contact list of 4,000

drivers he directly knew -- quite an

accomplishment given the transitory nature of

the work. These workers, many of them Yemeni and

other recent immigrants, worked to strengthen

their collective efforts to defend their rights.

These organizing

drives were largely responsible for the passage

of California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) -- a state

law classifying rideshare and delivery drivers

of the network companies as employees, not

"independent contractors." AB5 puts the burden

of proof for classifying individuals as

independent contractors on the hiring entity.

AB5 entitles workers classified as employees to

avail themselves of California's minimum wage

laws, sick leave, and unemployment and workers'

compensation benefits, for which companies must

pay payroll taxes These organizing

drives were largely responsible for the passage

of California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) -- a state

law classifying rideshare and delivery drivers

of the network companies as employees, not

"independent contractors." AB5 puts the burden

of proof for classifying individuals as

independent contractors on the hiring entity.

AB5 entitles workers classified as employees to

avail themselves of California's minimum wage

laws, sick leave, and unemployment and workers'

compensation benefits, for which companies must

pay payroll taxes

AB5 was signed into law on September 18, 2019,

and came into effect January 1, 2020. Uber and

Lyft responded by refusing to abide by the law

or court injunctions requiring them to classify

the workers as employees. Drivers took action by

organizing demonstrations in San Francisco and

Los Angeles. The companies then formed their own

cartel to have their own law, Prop 22, passed

through a corrupt electoral process on November

3. They hired "labour" lawyers to write the Prop

22 legislation for the November 3 referendum in

a manner which specifically favours their

private interests in opposition to the interests

of workers. The target of the legislation is

clearly spelled out in Prop 22:

"Notwithstanding any other provision of law,

including, but not limited to, the Labour

Code, the Unemployment Insurance Code,

and any orders, regulations, or opinions of the

Department of Industrial Relations or any board,

division, or commission within the Department of

Industrial Relations, an app-based driver is an

independent contractor and not an employee or

agent with respect to the app-based driver's

relationship with a network company."

The network companies demand the right to force

individual workers to sign a company contract

before selling their capacity to work to the

company and beginning work. Prop 22 reads:

"A network company and an app-based driver

shall enter into a written agreement prior to

the driver receiving access to the network

company's online-enabled application or

platform." The contract denies the right of the

contracted workers to claim their rights

individually outside of what the contract

declares or to unite with other contracted

workers to defend their rights collectively.

To consolidate the legislated tyranny and to

deny any chance of it being overturned, the Prop

22 legislation reads in subdivision (a):

"After the effective date of this chapter, the

[California] Legislature may amend this chapter

by a statute passed in each house of the

Legislature by rollcall vote entered into the

journal, seven-eighths

of the membership concurring." (Emphasis

added.)

To make the point clear that tampering with the

legislation is not permitted, Prop 22 reads:

"No statute enacted after October 29, 2019, but

prior to the effective date of this chapter,

that would constitute an amendment of this

chapter, shall be operative after the effective

date of this chapter unless the statute was

passed in accordance with the requirements of

subdivision (a)."

In other words, any amendment or tampering with

the basic tenet of Prop 22 that network workers

are not really employees and must accept the

legislated terms of employment to work requires

"seven-eighths of the membership concurring."

Prop 22 exempts network companies from AB5 that

requires companies to grant workers employee

status based on an "ABC test." The test declares

a worker is an employee, rather than an

independent contractor, "if his or her job forms

part of a company's core business, if the bosses

direct the way the work is done or if the worker

has not established an independent trade or

business."

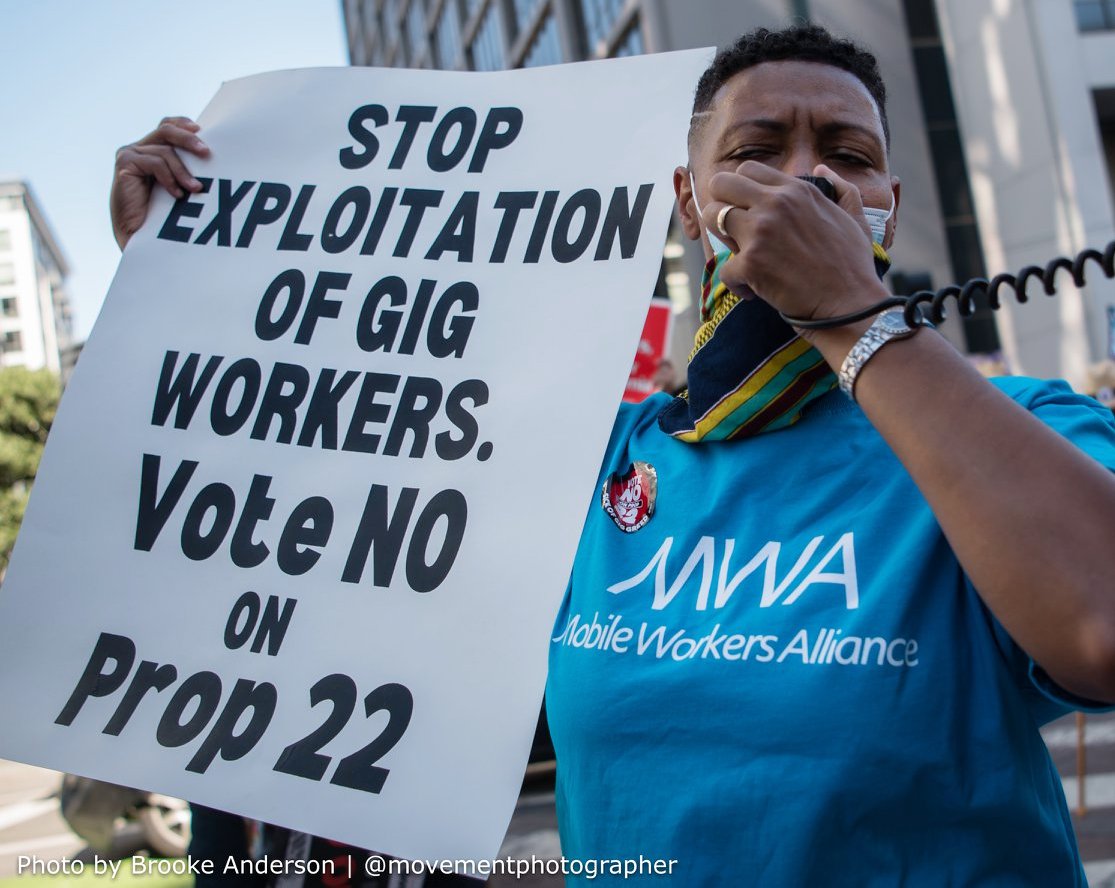

The drivers organized broadly against

Proposition 22 and the lies and disinformation

spread by the companies, claiming it would

benefit the workers. This included

demonstrations calling on people to vote no,

drawing more forces into the organizing efforts

and reaching out to the public with educational

materials.

Among their demands are: Set hourly minimum

pay matching New York City's $27.86 per hour

before expenses, the right to organize without

retaliation and recognition of independent

organizations of drivers to negotiate for

workers. Indicating their concern for the public

and environment they also asked the networks to

show the complete fare breakdown with Uber or

Lyft's take on the passenger's receipt and set

emission standards for all new vehicles added to

the platforms. In this manner the drivers are

striving to take up their social responsibility

to defend their interests and that of the

public. The network companies, on the other

hand, are fighting for the opposite, including

by failing to provide COVID-19 protection.

Prop 22 is a

means to criminalize organizing efforts while

also providing a constant supply of vulnerable

workers to exploit. Its aim to enshrine in law

that the companies have no social

responsibilities of any kind is not going to be

accepted by workers anywhere and will be fought

tooth and nail. The workers' movement in the

United States, Canada and internationally is

fighting for justice and modern arrangements

which affirm the rights of all. The workers'

movement does not recognize the definition of

rights said to be legal by the corrupt ruling

class which is in contempt of both the word

rights and the conception of rule of law. A

right is a matter of making the claims that

human beings must make to affirm their humanity.

If it is not even seen to be just, it will be

defied. Prop 22 is a

means to criminalize organizing efforts while

also providing a constant supply of vulnerable

workers to exploit. Its aim to enshrine in law

that the companies have no social

responsibilities of any kind is not going to be

accepted by workers anywhere and will be fought

tooth and nail. The workers' movement in the

United States, Canada and internationally is

fighting for justice and modern arrangements

which affirm the rights of all. The workers'

movement does not recognize the definition of

rights said to be legal by the corrupt ruling

class which is in contempt of both the word

rights and the conception of rule of law. A

right is a matter of making the claims that

human beings must make to affirm their humanity.

If it is not even seen to be just, it will be

defied.

The fact that the coalition of network

companies Uber, Lyft, Instacart, Postmates and

DoorDash banded together in California to

write and pass the legislation to block

organizing efforts and ensure a constant supply

of vulnerable workers, indicates they will do a

similar job in Canada where the oligopolies are

already acting to get legislation in their

favour through parliaments and legislatures.

Working people are setting an example by

stepping up their resistance and increasingly

organizing to reject the actions of narrow

private interests like Uber and Lyft. They are

taking up their social responsibility to defend

the rights of all and striving to take the

country in a new direction.

Workers' Forum is at the disposal of the

organizing efforts of all gig workers.

To guarantee the passage of Prop 22 during the

November 3 California referendum,

the network companies formed a cartel with a war

chest of over $200

million. They bombarded the people of the state

with relentless ads,

text messages, push notifications, emails and

even fliers included in

delivered packages. The Los Angeles Times

reports, "Yes on Prop

22 spent $628,854 a day. In any given month,

that ends up being more

money than an entire election cycle of

fundraising in 49 of

California's 53 House races." Delivery drivers

and cyclists were forced

to use Yes on Prop 22-branded packaging while

the apps themselves

badgered workers and even the people using them

for rides and delivery

to

vote Yes.

The network companies hired 19 public relations

firms to work on

the Yes campaign, some of which were already

notorious for having been

paid to prettify and defend Big Tobacco. The

network companies bought

civil society organizations to promote Prop 22

as something progressive

with a human face. For example, they made a

"donation" of $85,000 to a consulting firm run

by Alice Huffman, former

head of California's National Association for

the Advancement of

Coloured People (NAACP). The network companies

used the NAACP

"endorsement" to present Prop 22 as something

positive for the

descendants of African chattel slavery, further

confusing the issue for

many in California.

The network companies hired 19 public relations

firms to work on

the Yes campaign, some of which were already

notorious for having been

paid to prettify and defend Big Tobacco. The

network companies bought

civil society organizations to promote Prop 22

as something progressive

with a human face. For example, they made a

"donation" of $85,000 to a consulting firm run

by Alice Huffman, former

head of California's National Association for

the Advancement of

Coloured People (NAACP). The network companies

used the NAACP

"endorsement" to present Prop 22 as something

positive for the

descendants of African chattel slavery, further

confusing the issue for

many in California.

The PR firms with their vast connections in the

mass media blanketed

the state with Vote Yes on Prop 22 propaganda.

The Vote Yes campaign

bought digital, television, radio, and billboard

ads, and paid for

academic research suggesting workers would be

better off without their

rights codified in law. Uber and Lyft's chief

executives

undertook a media tour featuring threats to exit

the state if Prop 22

failed to pass. In the end, according to a poll,

over 40 per cent of

those who voted yes said they did so thinking it

was a vote in defence

of workers' rights and well-being. The workers

however have not been

deterred from their struggle. They continue to

fight and organize, not

only for their rights as workers but also as

women and immigrants, who

constitute a large portion of the workforce.

The Prop 22 referendum was imperialist

democracy on ugly display

using money and mass media to bring into being

legislation of, by and

for powerful private interests. The demand to

have the right to put

referendums on the ballot in California was part

of efforts by the

people to have a say in legislation. However, as

written, it does not

prevent the type of massive corrupt moneyed

campaign to vote Yes for

Prop 22 that took place. The same money and

electoral system that

pushed through Prop 22 pushes the two main

parties of the rich -- the

Democrats and Republicans -- into government in

California and

throughout the United States.

The fight against Prop 22 and for the rights of

network company

workers brought to the fore the problems with

the existing electoral

system and the need for democratic renewal. The

fact that the drivers

took their stand and fought against Prop 22

shows their recognition of the need to

have more of a say in political affairs and to

block the giant

monopolies from manipulating the public. Their

continuing struggle

shows they are rejecting efforts by the

monopolies to define who they

are and what their rights are.

The existing electoral process routinely

excludes large numbers of

workers, such as immigrants who are

undocumented, those in prison,

those not registered, etc. For Prop 22, an

estimated 32 per cent of the

voting age population secured its passage.

Another 22 per cent voted no

and the remaining 56 per cent did not vote --

meaning the large

majority did not support it. Similar figures

exist for statewide and

federal elections, where presidents are elected

with about 25 per cent

of the vote. It is not a process that represents

the people, their

concerns or solutions. The drivers, along with

the millions opposing

racist police killings, separation of immigrant

families, fighting for

equality and

justice indicate that the people are fighting

for control over their

lives and for a political system that embodies

that.

Note

Results of California Vote

on Proposition 22 in November 3, 2020

Election

Voters must be eligible to vote

in California election and register to vote 15

days prior to the vote.

Proposition 22 -- App-Based

Drivers and Employee Benefits -- For and

Against

Yes (for) = 9,874,555 58.6 per

cent of voters

No (against) = 6,979,133 41.4

per cent of voters

Total voters = 16,853,688

California population 2019 =

39,512,223

California population 18 years

and older = 30,621,973 (77.5 per cent)

Total voters on Prop 22 as

percentage of population 18 years and older =

55 per cent

Total voters voting Yes on Prop

22 as percentage of California population 18

years and older = 32 per cent

Total voters voting No on Prop

22 as percentage of California population 18

years and older = 22.8 per cent

October 1, 2019 -- 20,328,636

Californians registered to vote.

Registered voters as percentage

of California population 18 years and older =

66 per cent

Number of persons not

registered to vote but 18 years and older =

10,293,337

The California Secretary of

State says that the number of Californians

registered to vote as percentage of eligible

voters = 80.65 per cent

This means that the state's

estimate of eligible voters = 25,205,996

California population 18 years

and older = 30,621,973

California population 18 years

and older not officially recognized as

eligible to vote = 5,415,977

To be officially eligible to

vote a person must be:

- A

United States citizen and a resident of

California,

- 18 years old or older on Election Day,

- Not currently in state or federal prison or

on parole for the conviction of a felony (for

more information on the rights of people who

have been incarcerated, please see the

Secretary of State's Voting Rights: Persons

with a Criminal History), and

- Not currently found mentally incompetent to

vote by a court (for more information, please

see Voting Rights: Persons Subject to

Conservatorship).

For the complete text of

Proposition 22 click

here.

- K.C. Adams -

Imperialist network

companies force their social irresponsibility

into California law

Hundreds

of thousands of California workers involved in

the rideshare and

package delivery industry have been declared

non-workers in law. Yet,

in contradiction with their imperialist

definition, the oligarchs

holding political power have also forced terms

of employment, a

state-dictated collective agreement, on the

so-called "non-workers."

Needless to say, the rideshare and delivery

"non-workers" had no say or

control over their dictated terms of employment

nor the chance to give

their specific collective or individual approval

or disapproval. They

have however shown their rejection of the

dictate in Prop 22,

demonstrating and organizing against it and

continuing now despite its

passage.

Five imperialist

network companies involved in transporting

people and delivering prepared food have forced

into law a declaration that is anti-worker,

irrational in content and profoundly

irresponsible. Five imperialist

network companies involved in transporting

people and delivering prepared food have forced

into law a declaration that is anti-worker,

irrational in content and profoundly

irresponsible.

The

five network companies financed and pushed into

California law

Proposition 22 to avoid their social

responsibility to pay payroll fees

for workers' compensation for work-related

injury and illness,

unemployment insurance and company-paid health

care insurance agreeable

to the workers themselves, and to evade various

state mandated legal

norms on minimum wages, sick pay, overtime and

holidays. The legal

definition as "non-workers" also makes it more

difficult for network

company workers to organize into their own

collectives to defend their

rights and to legally negotiate terms of

employment, within collective

agreements with their employers. As the workers'

demands bring out,

these include increased wages, compensation for

all work, and efforts

to protect the environment and the public,

including better COVID-19

protections for them and passengers.

The five network companies at the forefront of

pushing social irresponsibility and drafting

government legislation are Uber, Lyft,

Instacart, Postmates and DoorDash. That the

state of California would even allow itself to

be manipulated into denying its social

responsibility to protect its people and agree

to powerful private interests dictating law

speaks volumes about the necessity for

democratic renewal, empowerment of the

people and a new pro-social direction for the

economic, political and social affairs of the

state and country.

California is home to a large array of

imperialist network companies such as Google and

others employing millions of workers. Those

workers are members of the modern socialized

workforce. Whether they sell their capacity to

work to others or even to themselves as

cooperatives they are socialized workers who

require civilized norms of employment befitting

the modern socialized productive forces over

which they must have a say and control.

By denying

rideshare and delivery workers their status as

workers, the imperialists are denying the

reality of the modern workplace as it presents

itself and the necessity at this time for

equilibrium in the relations of production. They

are denying that workplace injury and illness is

commonplace; they are denying that periodic

unemployment occurs from either a general or

localized economic crisis such as the pandemic;

they are denying that the rich oligarchs who are

driven by their aim for maximum private profit

ever abuse their employees and that workers must

unite to defend their rights and have as a

minimum the legal right to do so. They are

denying that the socialized forces of production

are the only institutions from which working

people can acquire a living and find a means of

subsistence and are consequently forced to sell

their capacity to work to live; they are denying

that in general the imperialist economy consists

of a social relation between working people who

sell their capacity to work to those who own and

control the socialized means of

production. By denying

rideshare and delivery workers their status as

workers, the imperialists are denying the

reality of the modern workplace as it presents

itself and the necessity at this time for

equilibrium in the relations of production. They

are denying that workplace injury and illness is

commonplace; they are denying that periodic

unemployment occurs from either a general or

localized economic crisis such as the pandemic;

they are denying that the rich oligarchs who are

driven by their aim for maximum private profit

ever abuse their employees and that workers must

unite to defend their rights and have as a

minimum the legal right to do so. They are

denying that the socialized forces of production

are the only institutions from which working

people can acquire a living and find a means of

subsistence and are consequently forced to sell

their capacity to work to live; they are denying

that in general the imperialist economy consists

of a social relation between working people who

sell their capacity to work to those who own and

control the socialized means of

production.

By

doing so, the imperialists have brought to the

fore two projects that

the working class is taking up: one, the

organizing of workers into

powerful independent collectives that defend the

rights of all and the

right of workers to a say and control over their

terms of employment.

The independent organizations of the rideshare

and delivery drivers as

well as the many that have formed as part of the

fight for equality,

justice and accountability, are examples in this

direction. Two, the

necessity to organize for democratic renewal to

overcome the current

tyrannical rule of private interests and bring

into being a genuine

government of the empowered people, by the

empowered people and for the

empowered people.

- Keith F. Eberl -

The writer Keith Eberl is a rideshare driver

in Los Angeles and organizer for Rideshare

Drivers United an independent driver-created

and driver-led association of 19,000

California drivers.

Attorneys for

Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash wrote the 2020

California ballot initiative known as

Proposition 22. Contrary to the companies'

deceptive ad campaign and intimidating messages

to their workers, Prop 22 does not

preserve driver flexibility or save drivers from

politicians. What Prop 22 does do is

change current law so the companies can shift

their costs to the driver and diminish or remove

drivers' rights, protections, and benefits. Prop

22 will also block drivers' ability to organize

so they can't collectively bargain a contract.

In addition, this proposition will block local

governments from writing or enforcing

protections for drivers, such as in a crisis

like COVID-19, and will leave governments

footing the bill for the basic health and

welfare of drivers. Attorneys for

Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash wrote the 2020

California ballot initiative known as

Proposition 22. Contrary to the companies'

deceptive ad campaign and intimidating messages

to their workers, Prop 22 does not

preserve driver flexibility or save drivers from

politicians. What Prop 22 does do is

change current law so the companies can shift

their costs to the driver and diminish or remove

drivers' rights, protections, and benefits. Prop

22 will also block drivers' ability to organize

so they can't collectively bargain a contract.

In addition, this proposition will block local

governments from writing or enforcing

protections for drivers, such as in a crisis

like COVID-19, and will leave governments

footing the bill for the basic health and

welfare of drivers.

I should know. I have been a full-time

rideshare driver for four years and an organizer

with Rideshare Drivers United for three.

Rideshare Drivers United is an independent, Los

Angeles-based, driver-created and driver-led

association of 19,000 California rideshare

drivers. Our goal is to become a union and win a

voice on the job, fair pay, and dignity for the

work we do. [...]

From their start, the app-based companies'

business models have depended on using drivers

like employees while treating them as

independent contractors so that the companies

can shift their costs to the drivers. This is

why we have seen and heard so much in the news

about class-action lawsuits against Uber and

Lyft for misclassifying their drivers as

independent contractors.

In 2018, the California Supreme Court ruled in

favour of truck drivers who sued the Dynamex

company for the same reason. The court adapted

what's known as the "ABC test" used by

Massachusetts and New Jersey to determine that

the truckers were in fact employees of the

company, and so the "Dynamex" decision became

the law of the land in California. In 2019, this

test was written into a California bill called

"AB5" to define what an independent contractor

is. [...]

None of Prop 22 originated from workers or

their elected representatives. In fact, because

the companies have been ignoring current wage

laws, Rideshare Drivers United built an online

tool to help more than 5,000 California drivers

file wage claims with the California Labor

Commission against Uber and Lyft for unpaid

wages, expense reimbursements, and damages

totaling over $1.3 billion. This action was

called "People's Enforcement of AB5." [...]

In June of this year, the California Attorney

General sought an injunction from the courts to

force the companies to cease misclassifying

their workers and comply with the law. Instead,

in old-style union-busting fashion, Uber and

Lyft began to incite fear in their workers and

the public by threatening to close up shop in

California if the injunction was granted,

putting tens of thousands of drivers out of

work. News outlets across the country lit up

with sensational headlines that rideshare in

California was facing imminent shutdown. "We'll

have to close the factory!" the company bosses

said. [...]

In the meantime, the companies have launched a

massive misinformation blitz to promote their

ballot initiative. Deceptive ads are showing up

in every corner of mass media and electronic ad

space you can find, including in the passenger

and delivery customer apps. [...]

So, after threatening to fire everyone and

leave town, company bosses are now barraging our

work apps with pop-up messages [...]. This is

happening every day, several times a day, in our

work space -- the apps on our phones.

[... T]hese

faceless bosses try to confuse us. We are

presented with the message: "Prop 22 is

progress. Prop 22 will provide guaranteed

earnings and a healthcare stipend." Again, there

is no human interaction here, and no explanation

of what those are exactly or why that isn't

happening already, but we are presented with two

buttons: one marked "Yes on Prop 22" and the

other "OK." [... T]hese

faceless bosses try to confuse us. We are

presented with the message: "Prop 22 is

progress. Prop 22 will provide guaranteed

earnings and a healthcare stipend." Again, there

is no human interaction here, and no explanation

of what those are exactly or why that isn't

happening already, but we are presented with two

buttons: one marked "Yes on Prop 22" and the

other "OK."

Spreading fear and confusion amongst workers is

a classic union-busting tactic. (On October

22, drivers filed a lawsuit against Uber for

violating a California law that prohibits

employers from trying to influence employees'

political activities by threatening a loss of

employment). [...]

[Prop 22] would grant app-based transportation

and delivery companies a complete exemption from

AB5, freeing them from complying with

California's labour laws (which they have

flouted since their founding) and signalling

that corporations can establish a permanent

class of unprotected workers.

Prop 22 would strip or severely diminish

app-based rideshare and delivery drivers of our

right to a minimum wage, overtime, expense

reimbursement, healthcare, sick leave, workers

comp, safety regulations, anti-discrimination,

and the right to organize. But, it will still

allow the companies to use us workers like

employees because of the way they control us.

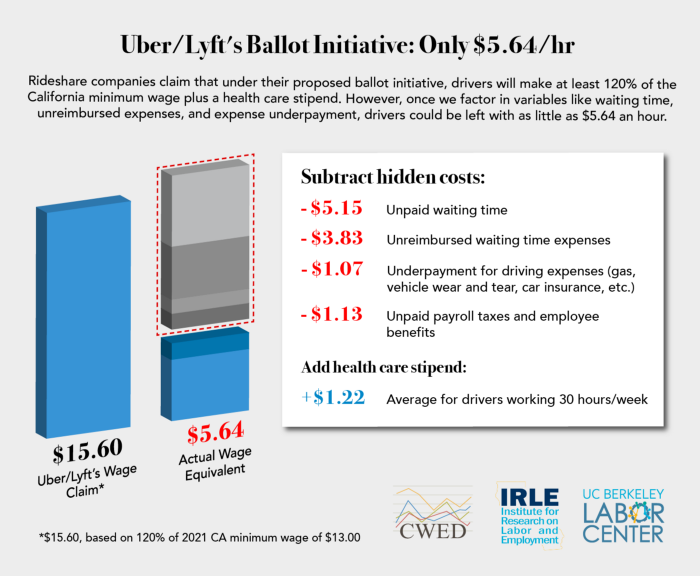

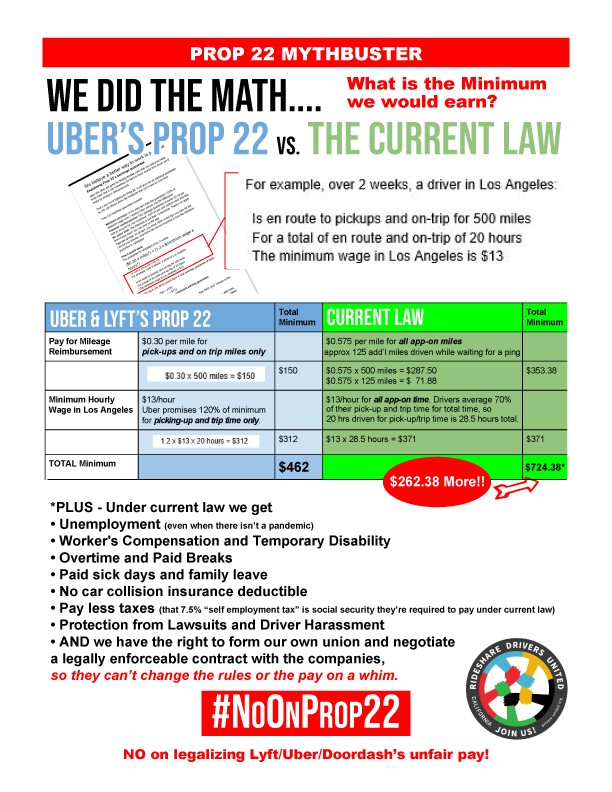

Let's have a look at the earnings and

healthcare aspects of Prop 22. Prop 22

eliminates basic workplace benefits and replaces

them with a new, lower "earnings guarantee" and

a "healthcare subsidy" payment designed to save

companies from footing the bill for the expenses

they would otherwise have under current law.

The "earnings guarantee" of pay would be equal

to 120 per cent of the minimum wage (that would

be $15.60 in 2021 when the California minimum

wage will be $13), but drivers would only be

paid for "engaged time." "Engaged" means "from

when an app-based driver accepts a rideshare

request or delivery request to when the

app-based driver completes that rideshare

request or delivery request." Drivers would not

be paid for time waiting for a ride request.

Since part of the company's business model is to

saturate some areas with an oversupply of

drivers, wait times can consume large parts of

every hour a driver is on the road, including

spending 30-45 minutes in the driver queue at

Los Angeles International Airport.

"Per-mile compensation for vehicle expenses"

under Prop 22 would be 30 cents per "engaged

mile" [...]

If drivers are in a densely populated urban

area that is saturated with other drivers and

have few places to stop legally, like downtown

Los Angeles on a weekday, drivers may find

themselves constantly on the move with no fare

or order to pick up and deliver. They will not

be compensated for miles driven without a rider

or delivery to pick up, even though they are

waiting for the company to send them work.

Under current law, however, workers must be

reimbursed for mileage at the standard IRS

mileage reimbursement rate, which for 2020 is

calculated at 57.5 cents per mile and isn't

restricted to "engaged miles" when calculating

reimbursement.

Drivers also know from experience that the

companies will not compensate us for downtime

caused by the need to stop work to clean after a

messy trip, to file an emergency report in the

app, or to respond to a company error or false

complaint against us that has caused a loss of

income, a suspension, or wrongful termination.

UC Berkeley Labor Center's wage assessment of

the ballot initiative found that "after

considering the multiple loopholes in the

initiative, the pay guarantee estimate for Uber

and Lyft drivers is actually to be the

equivalent of a wage of $5.64 per hour." The

authors say, "Not paying for [logged in but not

"engaged"] time would be the equivalent of a

fast food restaurant or retail store saying they

will only pay the cashier when a customer is at

the counter. We have labour and employment laws

precisely to protect workers from [this] kind of

exploitation." Prop 22 means workers would have

to work longer shifts just to earn a living wage

-- putting in more than 40 hours a week with no

overtime pay.

Let's look at this the way a driver like me

does -- basic. How much will I get paid for a

fare from Los Angeles Airport (LAX) to San

Clemente at night? A quick "ask Google" and it's

65 miles to San Clemente and one hour in no

traffic. I know from experience that an Uber X

fare like this pays out at roughly $52. (Pretty

lousy for the distance).

The exact fare I'd get paid would be $51.65,

because the Uber X fare in Los Angeles is at a

rate of $0.60/mi and $0.21/min (or $12.60/hr)

for the time when a passenger is on board.

If Prop 22 passes and it's now 2021, that same

fare would pay me at a rate of $0.30/"engaged

mile" and $15.60/"engaged hour" (or

$0.26/"engaged minute"). Again, "engaged time"

is from when I accept a ride request until I

drop off the passenger.

Now, I work mostly at LAX.... For the sake of

this exercise, let's say I would travel about

one mile from the holding lot and it would take

about 10 minutes until I had my passenger on

board if someone's waiting at the curb. At Prop

22 rates, that part pays $2.90. The part where I

have a passenger on board and drive all the way

to San Clemente at Prop 22 rates? That pays

$35.10. So the total payout for the same ride

from LAX to San Clemente at Prop 22 rates is $38

or $13.60 less than current Uber X rates.

Under current law, drivers have the right to be

compensated for all on-the-clock time,

reimbursed for work-related mileage at more than

double the Prop 22 rate, and reimbursed for work

related expenses. As employees, we have the

right to organize and negotiate a contract for

better than the bare minimum.

If Prop 22 passes, the app companies would

replace health insurance coverage with their

smaller "healthcare subsidy" payments designed

to save the companies money at the expense of

their workers' health and safety. After sifting

through the convoluted language of Prop 22 on

this health benefit, we find that the companies

have defined the maximum subsidy that any one of

them will pay a worker as just 82 per cent of

"the average statewide monthly premium for an

individual ... for a Covered California bronze

health insurance plan."

Covered California is where you shop for

"Obamacare." The lowest costing insurance plans

are in the "bronze" tier where you find plans

with the lowest premiums, but highest

deductibles and the least coverage. There are 12

bronze plans, but who you are and where you live

can have a dramatic effect on what your premium

is. So, how do you figure out the average for

the whole state across 12 bronze plans? Someone

at Covered California needs to figure it out

because Prop 22 is going to require them to

publish it. Until then, we don't know what we're

voting for.

Otherwise, there are two subsidy tiers you have

to work for to earn: either 41 per cent of that

bronze average, or 82 per cent of that bronze

average. Which one you earn depends on whether

you maintain an average of at least 15 "engaged

hours" or at least 25 "engaged hours" of work,

per week, for three months, respectively. If you

miss both you could get nothing. All of these

are paid to you quarterly. You can earn a

subsidy from more than one company, but there is

no provision for combining hours from them to

reach 15 hours or 25 hours of "engaged time".

The other conditions are: you must get and

provide proof of your own insurance with you

listed as the policyholder (not necessarily

through Covered California, apparently), it

cannot be sponsored by an employer, and it can't

be Medicare or Medicaid.... The authors of

"Rigging the Gig" found "as recent studies

(funded by the industry) have indicated, drivers

spend as much as 37 per cent of their time

logged into a transportation app, but without a

passenger." This means that most drivers would

have to log an extra 37 per cent more time on

the app -- more than 39 hours per week -- to

qualify for the top tier benefit of 82 per cent.

So, you will have committed yourself to paying

for an insurance plan that they will help you

pay for if you work enough hours (many of them

unpaid), but you have to pay for it yourself

until you get your quarterly payment from them

-- if there is one. God help you if you decide

to go on vacation/your car breaks down for a few

days/you have a family emergency or you get

injured and are unable to work. Not only will

you have no paid vacation, reimbursement for

repair expenses, or bereavement leave or sick

leave, you could also lose your premium

assistance, not for just one month but a whole

quarter.

Looking at Prop 22's "healthcare subsidy" as an

experienced rideshare driver, I immediately see

another big problem. I'm used to Uber's and

Lyft's performance-based bonus incentives, and

I'm also used to circumstances beyond my control

causing me to miss them. I still remember being

out driving at 3 am on a Monday needing just two

more L.A. fares before 4 am to score a big

bonus, and then catching one deep into Orange

County. Or worse, knowing that I did earn a

bonus, but someone at a call center refused to

give it to me over a location discrepancy

between the map display in the app and their GPS

records. So, now we're going to play that game

with my healthcare? Right. I stopped chasing

bonuses a long time ago because they are

unpredictable and unreliable as a source of

income.

This is Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart, and

Postmates' idea of healthcare. Cross your

fingers and take your best shot. These are not

rules for a new program they are rolling out.

This is what they are trying to put into law.

Their message: "If you want a stable healthcare

subsidy, try a taxpayer-funded one from Covered

California."

If you've ever heard the term "portable

benefits," this is what that will look like for

employees who get dropped from employee status

to a category such as the one that Prop 22 will

create, sometimes called a "dependent worker."

This is the future of work.

Keep all of that in mind as you read ahead.

The COVID-19 crisis has made conspicuous the

injustice communities of colour and immigrants

face when it comes to healthcare, especially for

app-based rideshare and food delivery workers

who are a majority of that workforce. In a May

2018 report released by the UCLA Labor Center,

of the 260 rideshare drivers UCLA surveyed from

around Los Angeles, 38 per cent were Latino, 23

per cent were Black, and 35 per cent were

foreign-born. Two years later, a description of

the app-based workforce in San Francisco emerged

in a study published by UC Santa Cruz Institute

for Social Transformation. In their survey of

643 app-based workers, 29 per cent were Asian,

23 per cent were Hispanic, 12 per cent were

Black, 13 per cent identified as multiracial or

other, and 56 per cent were foreign-born.

The Centers for Disease Control finds that

COVID-19 is taking a greater toll on those

communities because they have less access to

healthcare, sick leave, safe work environments,

and workers compensation. California,

unfortunately, is a potential case study. In a

July 15 article, the Los Angeles Times published an

analysis of statewide data finding that "for

every 100,000 Latino residents, 767 have tested

positive. The Black community has also been hit

particularly hard: for every 100,000 Black

residents, 396 have tested positive. By

comparison, 261 of every 100,000 white residents

have confirmed infections." L.A. County

officials were quoted as saying, "The underlying

reasons why communities of color are

disproportionately impacted by worse outcomes of

COVID is also related to longstanding structural

and systemic issues, including racism and

historical disinvestments, that L.A. County is

working to address and mitigate amidst this

pandemic." [...]

Meanwhile, drivers who are not eligible for

unemployment benefits or still need to work and

continue to drive have been forced to risk their

health and that of their families in order to

make a living. That is a choice that no worker

should have to make. Rideshare Drivers United

lost one of our own activists in San Diego to

COVID-19 in this way, and 28 other members

reported having been sick in an internal poll.

[...]

Early in the crisis the companies had been slow

to provide drivers with protective equipment

needed during the pandemic, including face

masks, sanitizer, disinfectant, and barriers

between drivers and passengers. [...]

Unemployment

The COVID-19 crisis has shown just how critical

unemployment insurance is to app-based rideshare

drivers and delivery workers. Since early this

year, the vast majority of rideshare drivers

have been put out of work due to the steep drop

in demand for their services and the health

risks associated with continuing to drive. [...]

Shortly after the COVID-19 crisis began, it

became apparent to lawmakers in Washington,

D.C., that a package of rescue legislation was

necessary and should provide money to people who

were put out of work. At that time, Khosrowshahi

(Uber CEO) lobbied Congress to provide some kind

of relief to his rideshare and delivery workers.

Ultimately this would come in the form of what

is known as Pandemic Unemployment Assistance

(PUA), a federally funded form of unemployment

insurance designed to get money to non-employee

workers who lost their income as fast as

possible.

The PUA unemployment benefit Khosrowshahi

lobbied so hard to "get" for his rideshare and

delivery workers is calculated on a worker's net

income, whereas in California the unemployment

insurance (UI) benefit is calculated on gross

earnings. Since app-based rideshare and delivery

drivers have such high expenses (that the

companies are supposed to reimburse drivers for

but don't) our net income is much lower than our

gross earnings. This means that our federal PUA

benefit would be much smaller than our state UI

benefit. [...]

If rideshare drivers and app-based delivery

workers applied for the fast, federal,

taxpayer-backed PUA benefit and not the state,

employer-backed UI benefit, this would help get

Uber off the hook for not paying into state UI

funds, even though Khosrowshahi knew it meant

his workers in states like California would get

a lot less money. That didn't work in New York

or, ultimately, in California where Rideshare

Drivers United not only worked to help thousands

of drivers navigate California's overwhelmed

unemployment insurance system to get their state

UI benefits, but also engaged with labor

advocates to cajole the state labor department

into reforms.

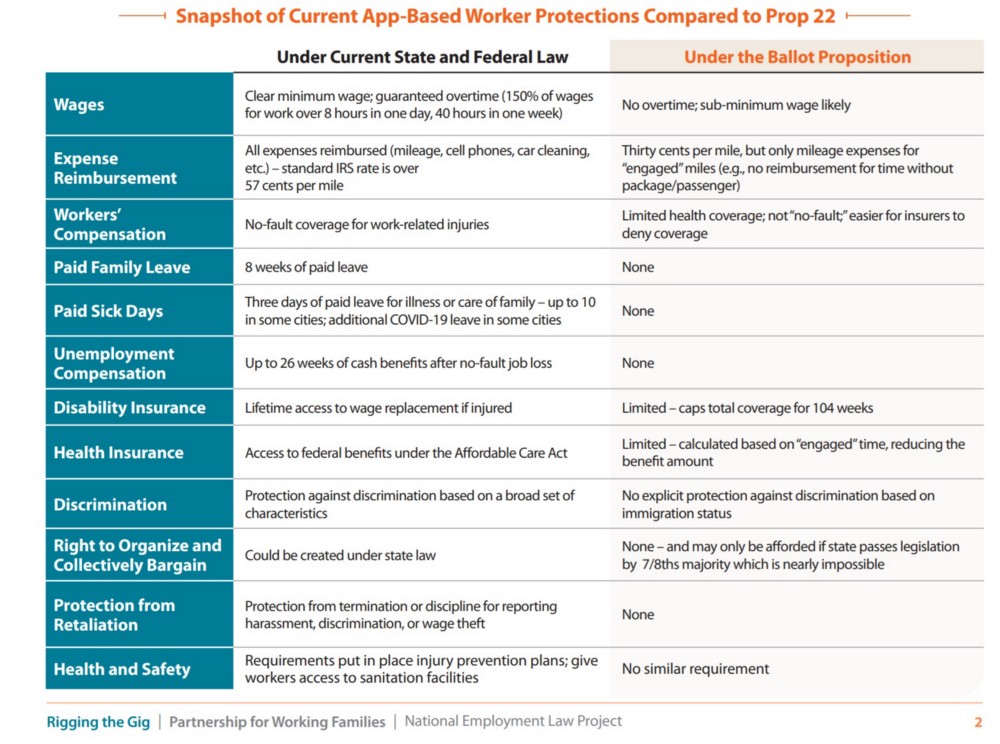

Click to enlarge.

Grievous Threat

A "Yes" vote on Proposition 22 would create a

permanent underclass of workers in California

and set a disastrous precedent for workers

everywhere.

If passed, Prop 22's concepts could infect

other industries and embolden other

billion-dollar companies to bankroll their own

initiatives using Prop 22 as a blueprint for

creating new classifications for their own

workers. In this way, companies could escape

labour laws and boost profits by shifting costs

to their workers.

In his August 10 op-ed in the New York Times,

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi spoke of his vision

for the future of work claiming that labour laws

are outdated and unfair to his workers, and that

there needs to be a "third way" or a new

category of worker. He has the audacity to speak

for the needs of his own workers while heading a

company built on using technology to exploit

them. His is not the only voice with that

message here, having co-authored a similar op-ed

last year with Lyft's cofounders Logan Green and

John Zimmer.

This

twisted, disingenuous narrative of the worker

victimized by outdated

labor laws has been repeated in statements by

politicians, and in

opinion pieces in major business news outlets in

the Northeast. A

professor at NYU Stern School of Business and an

analyst for MKM

Partners turned up on Bloomberg TV on August 11

(1:08:00 mark) and 20

(1:50:15 mark), respectively. Both recited

Khosrowshahi's key op-ed

points, but they also blamed politics for Uber

and Lyft's troubles, not

the companies themselves for ignoring the law.

Both guests either

ignored or were oblivious to the influence of

the rideshare companies'

own workers (and Rideshare Drivers United) on

the course of events.

[...]

Summation

Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart, and Postmates

are trying to undermine the gains workers in the

United States have won through over 150 years of

struggle for self-determination and the rights

and protections we have today. These companies

need to be stopped here.

A Yes vote on Prop 22 will allow billion-dollar

outlaw rideshare and delivery companies to

increase their profits by changing the rules to

fit their broken, exploitive business models.

Proposition 22, if it passes, will require a 7/8

vote of the California legislature to amend or

repeal it.

Other countries have already begun to bring

these outlaw companies to justice by declaring

that their workers have employee rights.

Californians must participate by voting NO on

Proposition 22 and set an example for the rest

of our country to follow.

Rideshare Drivers United urges all California

voters to VOTE NO on Prop 22, stand in

solidarity with app-based workers, hold these

giant tech companies accountable, and help us

keep the rights, dignity, and respect we

deserve.

The future of workers depends on it.

For more information visit: drivers-united.org

and NoOnCAprop22.com

For the full article, click

here.

Rideshare Drivers United reports that many

workers in their sector are not officially

considered eligible voters in California. They

would not have been able to vote on

Proposition 22 even though it directly affects

their lives as it contains an imposed

collective agreement detailing certain terms

of their employment.

The following executive summary is from a

recent study of ride-hailing and delivery

workers in San Francisco.

On-Demand and On-the-Edge: Ride Hailing and

Delivery Workers in San Francisco,

Chris Benner, PhD, October 8, 2020

Executive Summary

The coronavirus crisis has made visible a range

of essential workers -- grocery store workers,

cleaning staff, home health aides and others --

who in normal times are often ignored or taken

for granted. One category of these essential

workers that has gained particular attention in

this moment are on-demand meal and grocery

delivery workers. Working for well-known

companies like DoorDash, GrubHub and Instacart,

these workers are delivering essential food and

other supplies to people staying at home in the

midst of the shelter-in-place orders. The jump

in demand for these services highlights how

important these on-demand services are in the

midst of our collective efforts to maintain

physical distancing to limit the spread of

COVID-19.

Yet these on-demand food delivery workers,

along with on-demand ride-hailing workers who

fill a similar role in providing transportation

services to other essential workers right now,

are tremendously vulnerable. In providing these

services, both before and during the

shelter-in-place orders, they are vulnerable

both to contracting and spreading the

coronavirus. Their health vulnerability

underscores their financial vulnerability, as

prior to the virus outbreak, they were already

struggling to make ends meet. Being classified

by the on-demand platform companies as

independent contractors, they are also

particularly susceptible to not having health

insurance, paid sick leave, or access to

unemployment benefits.

In May, we released the results of a unique,

in-person representative survey of ride-hailing

and food delivery workers that we conducted and

then suspended when the pandemic hit, as well as

a follow-up online survey. The central findings

were simple and clear -- for a large portion of

this workforce, despite this being full-time

work, they were financially vulnerable before

the outbreak, and the crisis is pushing many of

them to the brink.

Now we have new data from a second in-person

representative survey we conducted in July and

August, focusing on food and grocery delivery

workers from three apps: DoorDash (114 surveys

completed), Instacart (114) and Amazon Fresh

(39).

One note about methodology. Both surveys were

designed to be representative samples of

on-demand work being done in the city, not of

all on-demand workers. This is important.

Representative samples of all people who do

some work for on-demand app companies show many

people working for short periods of time, or

earning only a small portion of their earnings

from this type of work. But we developed two

representative samples based on the actual work

being done in the city, which we believe is a

better basis for understanding labour practices

and developing labour market policy. Our

understanding is that this is the first study of

its kind done anywhere in the United States at

this scale.

The key findings emerging from the new summer

survey focused on DoorDash, Instacart and Amazon

Fresh include the following:

Highly Diverse Workforce

As with the winter survey, we found that this

workforce is highly racially and ethnically

diverse:

- 76 per cent of those surveyed are people of

colour, and 39 per cent immigrants.

- Women and non-gender binary people perform 39

per cent of the food and grocery delivery work,

including a slight majority of Instacart work.

Our survey of ride-hailing workers was much more

male-dominated.

Financially Struggling

All three surveys we've conducted of this

workforce continue to reveal how they are

struggling to make ends meet. According to the

latest survey:

- One-quarter of this workforce is reliant on

some form of public assistance, including 35 per

cent of Amazon Fresh and 33 per cent of DoorDash

workers. This public assistance includes

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF),

food stamps, housing vouchers, Supplemental

Security Income or the Supplemental Nutrition

Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

- One-fifth of these food and grocery delivery

workers are on food stamps.

- 14 per cent do not have health insurance.

Not a Gig for Most People

As with our winter survey, our latest survey

continues to reveal that app-based delivery work

is largely being performed by full time workers.

- 71 per cent obtain at least three-quarters of

their monthly income from platform work, and 57

per cent rely entirely on platform work for

their monthly income.

- Workers averaged 32 hours per week working

for all the apps, and 30 hours per week for the

app they were surveyed on. Instacart workers

were more likely to work longer hours.

- Nearly one-third are supporting children

through their platform work.

- While there was more longevity among

ride-hailing and food delivery workers prior to

COVID, our latest survey found that 70 per cent

of food and grocery delivery workers have worked

on the apps for less than six months.

Earnings from App-Based Work Are Low

Our latest survey continues to find that after

expenses, earnings from app-based delivery work

are very low.

- While workers average $450 from this work,

after adjusting for mileage expenses, they

average only $270 per week.

- Instacart workers had the highest average

weekly earnings of the apps surveyed ($500); yet

after expenses, those earnings dropped below the

other apps to just $235 per week.

- Nearly one third of workers' time spent

performing food and grocery delivery work is

unpaid time (e.g. driving to the pick-up

location, waiting for orders).

- 18 per cent of DoorDash workers earned an

estimated $0 after deducting mileage expenses

(calculated using Internal Revenue Service

mileage reimbursement rate of $.575 cents per

mile and the survey respondents' estimated

weekly mileage).

Platform Companies Structure Job

Opportunities

Some of the survey findings point to platforms

managing job opportunities in ways that would

likely support claims that these workers are

employees under the "ABC" test codified in

California Assembly Bill 5.

- When workers decline certain job offers, 56

per cent are not offered work for a period of

time, including 60 per cent from Amazon Fresh,

63 per cent of DoorDash, and 51 per cent of

Instacart.

- 25 per cent of DoorDash workers were offered

fewer bonuses and incentives after declining

work.

- 17 per cent of workers were threatened with

deactivation by those apps.

Bicycle Delivery a

Popular but Dangerous Mode of Travel

- More than a quarter of this workforce uses a

bicycle as their primary mode of travel for

deliveries.

- 70 per cent feel unsafe delivering food this

way, and almost one-third stated that they had

felt physically threatened while delivering food

on a bike.

Summary and Policy Implications of Combined

Results from Winter and Summer 2020 Surveys

- On-demand ride-hailing and delivery work in

San Francisco is performed predominantly by

people for whom it is close to full-time work

and their primary source of income.

- This is a highly diverse workforce, with

majority people of colour and a significant

immigrant population. Women also comprise a

large percentage of food and grocery delivery

workers.

- This workforce struggles to make ends meet,

and their circumstances have been made

significantly worse by the COVID-19 crisis.

- When expenses and both unpaid and paid work

time are fully accounted for, a substantial

portion of this workforce are estimated to make

less than the equivalent of San Francisco's

minimum wage (currently $15.59 hour).

- Many also don't receive other benefits they

would be entitled to under San Francisco law if

the companies were classifying them as

employees.

- Many are also not currently being adequately

supported during the COVID-19 crisis, either by

the app-based companies they work for, or by

public policies.

- These findings underscore the importance of

policy makers ensuring that existing city and

state employment laws are enforced for this

workforce, and finding new ways to address the

economic, safety and health, and public health

concerns facing this critical workforce.

Download the full survey results here.

Download October 2020 Supplemental Survey of

Delivery Drivers here.

To read the UC Santa Cruz News Press Release, click

here.

(To access articles

individually click on the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website:

www.cpcml.ca

Email: office@cpcml.ca

|