|

May 12, 2020- No. 33

Defend

Food Workers' Rights to Safe Working Conditions

Cargill

to Shut Down Meat-Processing Plant in Chambly, Quebec

• Help Protect Food Processing Workers!

ACT NOW! - United Food and Commercial Workers

United States

• The Coronavirus

Pandemic in U.S. Meatpacking Plants

• Conditions in the U.S.

Meatpacking Industry

• Keeping America's Food

Supply Strong Starts with Worker Safety - Marc

Perrone, President, United Food and Commercial Workers International

Union

Mexico

• Workers Strike Against

COVID Deaths in Border Factories

Defend Food Workers' Rights

to Safe Working Conditions

Cargill's meat-processing plant in Chambly,

located in

the Montérégie region, some 35 kilometres south

of

Montreal, is shutting down its operations, after 64 employees

contracted COVID-19, which represents 13 per cent of the local

workforce, the company confirmed in an email to the Canadian Press. The

company said it would

"temporarily idle" its facility. Everyone at the plant is now going to

be tested, and the operations are presently winding down, with all work

set to stop as of Wednesday, May 13. It is expected that the facility

could resume operations as soon as next week, should enough employees

test negative. Cargill employs 500 unionized workers at the

plant.

According

to Local 500 of the United Food and Commercial Workers, which

represents these workers, the first case of COVID-19 surfaced

around the end of April. On Wednesday, May 6, 171 employees were away

from work, either because they had the virus or had been in

contact with someone with symptoms. According

to Local 500 of the United Food and Commercial Workers, which

represents these workers, the first case of COVID-19 surfaced

around the end of April. On Wednesday, May 6, 171 employees were away

from work, either because they had the virus or had been in

contact with someone with symptoms.

The company said it's providing 80 hours of paid

leave

for any employee who requires time off because of COVID-19 and that

employees will be paid for up to 36 hours during the shutdown.

The company is suggesting that because of the

presence

of members of the same families employed by the factory or because some

employees live with people working in the health sector, that

this

is how the virus could have been transmitted. However facts are

very stubborn things, such as that measures were not taken seriously

by the company to protect the workers. In fact, as of March 23, Cargill

topped up the hourly wage of 400 of its unionized meat-processing plant

workers in Chambly and offered them a lump sum of $500 after eight

straight weeks of consecutive work, based on a regular shift. The

incentive was therefore definitely there, not for workers to look

after their health, but instead to continue working despite having

possible symptoms of COVID-19, thereby

facilitating its spread.

The Olymel pork slaughtering and cutting plant in

Yamachiche, Quebec, 150 kilometres northeast of Montreal, also had to

close its doors on March 29 after detecting at least nine cases of

the virus among its employees. It reopened on April 14.

Quebec pork-processing plant.

- United Food and Commercial

Workers -

Food processing workers at meat plants across

Canada

are working hard on the front lines to make protein products for

families and neighbourhoods across the country.

There

have been more than 1,400 confirmed COVID-19 cases of food processing

workers, so far. Some of these workers battling COVID-19 are in

critical condition and some have died. There

have been more than 1,400 confirmed COVID-19 cases of food processing

workers, so far. Some of these workers battling COVID-19 are in

critical condition and some have died.

The federal government recently announced $77

million

for food processing companies -- in response to the pandemic -- but the

details of how the money will be distributed are still uncertain.

Food workers must have a central role in

determining the conditions and criteria for the "Emergency Processing

Fund."

Tell the Government of Canada that taxpayer money

to

corporations must first guarantee the health and safety of workers --

and food workers must have a say in determining the conditions of their

own health and safety!

Show your support for food workers by sending a

letter NOW!

For weeks, Canada's food processing workers have

been

calling for the following measures -- recommended by food worker

advocates around the world -- and have received no commitments from the

federal government on these basic provisions:

- Ensuring that workers are able to work two

meters (6.5

feet) apart from each other throughout their working day. This is

possible through modification to work organization, work scheduling and

rest breaks. There may need to be changes to the design of the

workstations such as the installation of Perspex, Plexiglas or similar

material to

shield workers from potentially infecting each other;

- Reducing the speed and amount of product on the

line

to help ensure two-meter spacing between workers. This must be achieved

without eliminating any positions; and decisions regarding shifts, work

sharing arrangements, and overtime must involve the union;

- Provision of adequate hand washing and sanitizer

stations and increasing the number of breaks so handwashing may become

a routine part of the work;

- Ensuring regular, thorough cleaning and

sanitation of

the workplace, including restrooms and lunchrooms. All shared surfaces

(e.g. workbenches, door handles, handrails, and keyboards) must be

cleaned regularly;

- Provision of appropriate personal protective

equipment

(PPE) -- although this cannot be a substitute for appropriate

spacing between workers;

- Making arrangements for safe travel to and from

the workplace to minimize the risk of exposure to COVID-19; and

- Posting the agreed workplace protocols on

noticeboards

in languages that all workers can understand and maintaining regular

communication.

Protecting food workers and stopping the spread of

COVID-19 in Canada's food manufacturing facilities requires a

consistent approach guided by stakeholders -- unions and employers --

and enforced by government.

Food workers need action NOW!

United States

In the U.S., by May 8 more than five thousand

COVID-19 cases had been confirmed with ties to the U.S. meatpacking

industry. This number is likely vastly under-reported, given the lack

of testing. At least forty-nine meatpacking workers had died of

COVID-19 in 27 different plants across 18 states. Forty plants were

forced to close

temporarily, either because of public health orders or because so many

workers were sick that production was impossible.

The

Trump administration and the four oligopolies that control meat and

poultry processing in the U.S. -- Cargill, JBS, Smithfield and Tyson

Foods -- have been determined to keep meat packing plants open. On

April

28, Trump issued an executive order declaring that meat packing plants

were "critical infrastructure" allowing federal agencies to

now interfere and possibly overrule decisions made by local

authorities. As the outbreak grew across the U.S., the meatpacking

giants tried to hide the extent of the crisis in their plants. In some

states governors over-ruled the local health authorities in a bid to

keep the plants open. The

Trump administration and the four oligopolies that control meat and

poultry processing in the U.S. -- Cargill, JBS, Smithfield and Tyson

Foods -- have been determined to keep meat packing plants open. On

April

28, Trump issued an executive order declaring that meat packing plants

were "critical infrastructure" allowing federal agencies to

now interfere and possibly overrule decisions made by local

authorities. As the outbreak grew across the U.S., the meatpacking

giants tried to hide the extent of the crisis in their plants. In some

states governors over-ruled the local health authorities in a bid to

keep the plants open.

Nebraska is one state where JBS got its way and

the

Governor acted to block closure of a plant recommended by local health

officials. JBS has beef, pork, and poultry plants in 27 states. A

significant outbreak was identified by doctors at the JBS plant in

Grand Island, Nebraska as early as March 31, and the regional health

director asked the

governor to take action. The governor said no, citing Trump's order

that meat packing was "critical infrastructure."[1] Emails obtained

by the advocacy group ProPublica

show that JBS was intent on covering up the spread of COVID-19 within

its plants. "We want to make sure that testing is

conducted in a way that does not foment fear or panic among our

employees or the community," JBS chief ethics and compliance officer

Nicholas White wrote to the local health officials on April 15.

The virus quickly spread beyond the plant and

through

the community, with more than 1,200 cases in the city of 50,000, and 32

deaths, including one JBS worker. Limited testing, restricted only to

those with symptoms, identified 260 cases at the plant. There are now

outbreaks across Nebraska in meatpacking towns where Tyson Foods,

Smithfield Foods and Costco have plants. As the cases grew to

staggering levels, and hospitals were overwhelmed, the plants were

finally closed for deep cleaning. The Governor has announced that local

health officials will no longer be able to report COVID-19 data from

meat processing plant, calling it a "privacy" issue.

In plant after plant workers reported that they

were

sent back to work after informing supervisors and plant nurses that

they were sick. At the Cargill plant in Pennsylvania, a worker who died

of coronavirus told his children that a supervisor had instructed him

to take off a face mask at work because it was causing unnecessary

anxiety among

other employees. Other workers said they were told by supervisors not

to wear masks because only sick people should have masks, that health

professionals need them more, and that wearing them provokes fear at

the workplace.

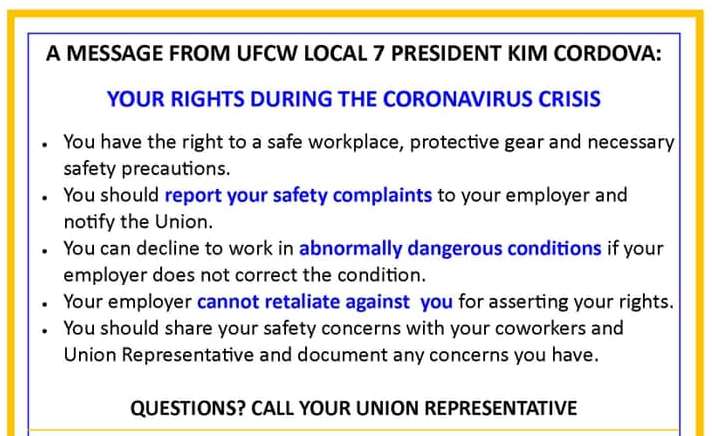

UFCW Local 7 at JBS meat plant in Greeley held May Day online

discussion.

In Greely, Colorado, the JBS plant was finally

closed,

long after public health officials reported by April 1 that emergency

departments were seeing large numbers of worker from JBS. Local health

officials urged JBS to do screening and social distancing or the plant,

and said otherwise the plant would be closed. JBS pushed back, claiming

the

governor was not in favour of closure. The plant was finally closed,

too late to stop the spread. Again with limited testing, 280 workers

tested positive, and seven of them have died.

At plant after

plant workers told similar stories about being told to

come to work after testing positive and to "keep it on the DL"

(down

low) or be fired; workers were told to return to work before the 14-day

quarantine ended even if they felt sick; workers clearly sick at work

were refused authorization to go home. Workers at the

JBS and Cargill plants in Alberta have given similar evidence. At plant after

plant workers told similar stories about being told to

come to work after testing positive and to "keep it on the DL"

(down

low) or be fired; workers were told to return to work before the 14-day

quarantine ended even if they felt sick; workers clearly sick at work

were refused authorization to go home. Workers at the

JBS and Cargill plants in Alberta have given similar evidence.

Just as similar were the claims by the owners that

the

problem was not the plants themselves but the "cultural practices" of

the workers. The workers are blamed for living in over-crowded

conditions, conditions imposed by the industry's low wages, and in

multi-generational households.

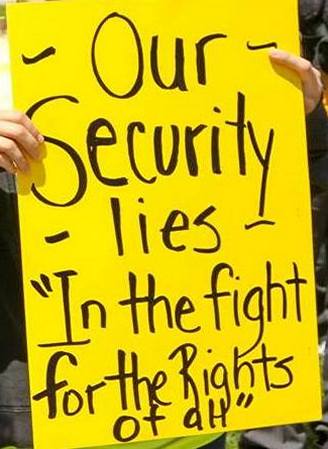

Workers have been speaking out to smash the

silence on

their living and working conditions, including non-unionized workers

who are finding ways to defend their rights. In Milan, Missouri a

worker, together with the Rural Workers Community Alliance, filed a

lawsuit that Smithfield was creating a public nuisance through its

failure to protect

workers from coronavirus infection. The complaint said that workers are

typically required to stand almost shoulder to shoulder, most often for

hours without being able to clean or sanitize their hands, and have

difficulty taking sick leave. The lawsuit also pointed out that workers

at the plant are given a disciplinary point if they take a day off,

which can eventually lead to dismissal. A federal judge dismissed the

suit on May 5, stating that Smithfield had taken "significant steps to

reduce the risk of an outbreak at the plant." In fact the plant had

taken a number of steps to provide protective equipment and increase

social distancing, but only after the lawsuit was filed.

Another measure used by the companies was to offer

temporary wage increases and bonuses to those workers who came to work

for every shift. This was also the case in Canada, although the

companies later claimed those quarantining would also get the bonus.

JBS USA offered a $600 bonus and $4 per hour wage increase to its

workers who

worked every shift. Those who were required to quarantine or

self-isolate were paid either regular wages or short-term disability,

according to the company. This was clearly an incentive to come to work

no matter what, an unconscionable act to pressure workers to come to

work even if they had symptoms of COVID-19.

Evidence

from workers across the U.S. leaves no doubt that the pressure on

workers to remain at work when sick or after exposure to COVID-19 was

deliberate, widespread and industry-wide, and carried out with the

support and collusion of governments at both the state and federal

level. In the face of this absolute contempt towards their

well-being, the workers, who are drawn from the most marginalized and

vulnerable sections of the U.S. working class, have shown their courage

and determination to defend their rights, and that the status quo is

not an option. Evidence

from workers across the U.S. leaves no doubt that the pressure on

workers to remain at work when sick or after exposure to COVID-19 was

deliberate, widespread and industry-wide, and carried out with the

support and collusion of governments at both the state and federal

level. In the face of this absolute contempt towards their

well-being, the workers, who are drawn from the most marginalized and

vulnerable sections of the U.S. working class, have shown their courage

and determination to defend their rights, and that the status quo is

not an option.

Note

1. That

same day, March 31, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney

said he had spoken to the Governor of Nebraska about the start of

construction on the Keystone XL pipeline, and the Governor had assured

him that all measures would be in place to carry out construction

safely during the pandemic. Did they also speak about keeping the

packing

plants open?

Food Chain Workers Alliance May Day 2020 facebook photo demands

protection for all

food workers.

COVID-19 has put the spotlight on the brutal,

dangerous

and back-breaking conditions of the workers in the meat and poultry

processing industry in the U.S. It has also shone the light on the

control by the meat packing oligopolies over the entire sector, with

all its negative consequences. The massive size and productivity of

these plants make the owners all the more determined to keep them open

at any cost, and the federal and state authorities have been their

willing servants. Workers and their unions are speaking out about the

conditions which gave rise to large outbreaks in the meat and poultry

plants.

In

addition to being dangerous, back-breaking, meat processing is an underpaid

job carried out by workers who are in many cases extremely vulnerable,

including undocumented workers, refugees, and other recent immigrants.

In the early 1980's, and before, the industry moved from major cities

to

rural areas. With the help of the Reagan administration, the meat

oligarchs set out to destroy the unions.

Meat packing is concentrated in the Great Plains

states

including South Dakota, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri, as well as in

Colorado, and Texas. The southern U.S. states also have significant

poultry production. There were not enough workers in the rural areas

for these massive plants, especially given the high turnover rate

because of the

terrible conditions of work. The companies instead functioned by

recruiting the most vulnerable and marginalized workers, including

refugees from southeast Asia and from Africa, and more recently from

Central and South America. About a third of the workforce is now

estimated to be made up of recent immigrants, and one in four

workers

are undocumented. Periodic raids conducted by Immigration and Customs

Enforcement (ICE) are used to enforce this vulnerability and to serve

as a

warning that attempts to defend their rights can have dire

consequences.

The brutality of the employers and the state in

their

service has no bounds. The

Atlantic

reported on a raid in August 2019

on seven poultry plants in Mississippi. Six hundred ICE agents, armed

with guns and body armour, seized 680 mainly Latino workers. The

Atlantic reported that their children gathered outside the

plant,

watching as their

parents were taken away. The raid exemplified state-organized racism,

taking place three weeks after a terrorist killing of 22 people in El

Paso, Texas where the gunman had targeted Mexican customers at a

Walmart

out of a desire to halt "the Hispanic invasion of Texas."

This vulnerable work force experiences danger

all round, working at breakneck speed with knives and saws,

with thousands

of workers in a plant working elbow to elbow. The floors are slippery

with water and blood. According to reported injuries, U.S. meat workers

are three times as likely to be injured as the average worker in the

U.S. and

seven times as likely to suffer a repetitive strain injury. Every week

there are amputations, fractures, serious burns, head trauma, and other

serious injuries. In the poultry plants the use of chemicals causes

respiratory disease and other illnesses.

Line

speeds in the U.S. are double those in Europe, and the speed is

dizzying. Industry averages in the U.S. range from 1,000 hogs per hour

to more than 8,000 chickens per hour. There is no way that workers can

follow guidelines such as covering their mouth while sneezing. Workers

in many plants face disciplinary action if they miss

even one piece of meat or poultry as it comes down the line at

lightning speed. In October 2019 the Trump administration eliminated

limits on production line speed in pork processing plants. Even as the

pandemic was raging, the Department of Agriculture issued waivers

allowing 15 poultry plants to increase their line speeds to as fast as

175

birds per minute. The statistics on the rate of injuries, which are

likely greatly under-reported, were compiled before speed restrictions

were removed. Line

speeds in the U.S. are double those in Europe, and the speed is

dizzying. Industry averages in the U.S. range from 1,000 hogs per hour

to more than 8,000 chickens per hour. There is no way that workers can

follow guidelines such as covering their mouth while sneezing. Workers

in many plants face disciplinary action if they miss

even one piece of meat or poultry as it comes down the line at

lightning speed. In October 2019 the Trump administration eliminated

limits on production line speed in pork processing plants. Even as the

pandemic was raging, the Department of Agriculture issued waivers

allowing 15 poultry plants to increase their line speeds to as fast as

175

birds per minute. The statistics on the rate of injuries, which are

likely greatly under-reported, were compiled before speed restrictions

were removed.

Some parts of a meatpacking plant, like the kill

floor,

are very hot, while others are like working in a refrigerator.

The cold is considered a factor in extending how long a virus can

survive outside a host, increasing the danger of coronavirus

transmission. It also contributes to the high incidence of arthritis

among packinghouse

workers.

The outbreaks which have taken a heavy toll on

packinghouse workers, their families and communities are a direct

result of the greed and drive for maximum profit of the oligarchs and

the fact that the public authority which could restrain them is no

more. It shows the need for a new direction in which the rights of the

workers are upheld, and

for a modern, sustainable agriculture and food industry with the aim of

providing safe and healthy food for all. The workers who are speaking

in

their own name and exposing the criminal negligence of the oligarchs

are defending their own rights, but also the rights of all to food

security and safety.

- Marc Perrone, President,

United Food and Commercial Workers

International Union -

Our country's food supply is facing an

unprecedented

threat from the coronavirus outbreak and hundreds of thousands of

American workers in meatpacking and food processing plants are seeing

new cases each week. As America's largest food and retail union, we are

hearing from our 250,000 workers in meatpacking plants every day about

how concerned they are for their safety and the danger facing our food

supply chain.

Make

no mistake, the threat to these workers and our food supply is real,

and without prioritizing worker safety, this collective threat will

only worsen. Make

no mistake, the threat to these workers and our food supply is real,

and without prioritizing worker safety, this collective threat will

only worsen.

To date, we have already documented the tragic

deaths of

21 of our meatpacking members and seen 5,000 workers infected or

exposed. As we have all seen, more than 20 plants have shut down to

slow the spread of the virus in South Dakota, Wisconsin, Iowa,

Pennsylvania, Missouri, Indiana and Minnesota.

Elected leaders in states across the country --

both

Republicans and Democrats -- have failed to act quickly enough to

address the urgent safety issues plaguing these plants and putting

these workers and our food supply at risk.

President Trump's new executive order invokes the Defense Production Act

to keep all meatpacking plants open and prevent

any further food supply shortages. But the new White House policy does

not mandate any of the strong worker safety standards needed to protect

these plants and employees from additional outbreaks of the virus.

What the president and far too many of our elected

leaders fail to recognize is that the way these meatpacking plants are

set up requires hundreds of workers to stand in close proximity to one

another for hours on end -- making physical distancing nearly

impossible. Without strong and enforceable safety measures and

protections, these plants

are essentially stationary cruise ships, facing the exact same safety

issues and just as likely to become coronavirus hot spots.

To be clear, shutting plants down is not something

anyone wants. U.S. meatpacking plant closures have already led to a 25

per cent reduction in pork slaughter capacity and a 10 per cent

reduction

in beef slaughter capacity. Our meatpacking workers want to work, but

we cannot ignore the dangerous safety issues that exist.

The most critical step to protecting America's

food supply is to put safety first for these workers and plants.

State governors claim to share our concern for our

country's food supply and worker safety. Every state must put their

commitment to safety into action by passing executive orders that

define clear and enforceable worker safety standards in every

meatpacking plant in the nation.

Strong state action to increase safety at

meatpacking

plants must include the enforcement of six-foot social and physical

distancing to the greatest extent possible and worker access to the

highest level of personal protective equipment (PPE) for when physical

distancing is not possible.

States must also ensure that daily testing is

available

for workers and their families, and employers must provide full paid

sick leave so that sick workers are able to stay home and never have to

choose between their health and a paycheck. States must fully enforce

recent CDC [Centers for Disease Control] guidelines on meatpacking and

work with federal inspectors

to

provide constant monitoring of these plants to ensure safety measures

are put into place immediately.

In the face of this unprecedented public health

crisis,

business and elected leaders must step up and work together with United

Food and Commercial Workers and our local unions across the country to

ensure that these essential workers have the essential protections they

need. Presidential executive orders that fail to prioritize worker

safety

will do nothing to protect our nation's food supply at a time when we

need it most.

We are already seeing beef shortages in fast food

restaurants and limits on meat purchases at grocery stores. Forcing

meatpacking plants to reopen without strong safeguards in place will

backfire and only further worsen the crisis our country is facing.

Americans need strong and swift action from our

country's leaders to put safety first at these meatpacking plants.

Truly protecting our food supply begins and ends with protecting our

nation's workers. This is the only way we can weather this storm and

ensure all Americans have the food they need during this deadly crisis.

Mexico

Living quarters of Maquiladora workers in Mexican barrio.

Workers' Forum is publishing below an article by David Bacon originally

published by TruthOut on May 5.

***

In Washington, DC, President Trump is trying his

best to

reopen closed meatpacking plants, as packinghouse workers catch the

COVID-19 virus and die. In Tijuana, Mexico, where workers are dying in

mostly U.S.-owned factories (known as maquiladoras) that produce and

export goods to the U.S., the Baja California state governor, a former

California Republican Party stalwart, is doing the same thing.

Jaime Bonilla Valdez rode into the governorship

in 2018

on the coattails of Mexican President Andrés Manuel

López

Obrador. And at first, as a leading member of López

Obrador's

MORENA Party, he was a strong voice calling for the factories on the

border to suspend production.

López Obrador himself was criticized

for not

acting rapidly enough against the pandemic. But in late March, in the

face of Mexico's rising COVID-19 death toll, he finally declared a

State of Health Emergency. Nonessential businesses were ordered to shut

their doors, and to continue paying workers' wages until April 30.

Bonilla's

Labor Secretary Sergio Martinez applied the federal government's rule

to the foreign-owned factories on the border, producing goods for the

U.S. market. Again, only essential businesses would be excepted.

When news spread that many factories were defying

the

order to close, Bonilla condemned them. "The employers don't want to

stop earning money," he said at a news conference in mid-April. "They

are basically looking to sacrifice their employees." But now, a month

later, he is allowing many non-essential factories to reopen.

Explaining the about-face are two competing

pressures.

At first, workers in the factories took action to shut them down, a

move widely supported in border cities. But as the owners themselves

resisted, they got the help of the U.S. government. The Trump

administration put enormous pressure on the Mexican government and

economy,

vulnerable because of its dependence on the U.S. market.

Now as the factories are opening again, the deaths

are still rising.

Strikes Start in Mexicali

Although Baja California is much less densely

populated

than other Mexican states, it's now third in the number of COVID-19

cases, with 1,660 people infected. Some 261 have died statewide, and

164 in Tijuana alone. That's more deaths than 131 in neighboring San

Diego, a much larger metropolis. Fifteen per cent of those with

COVID-19

in Tijuana die, while only 3.5 per cent die in San Diego. As is true

everywhere, with the absence of extensive testing, no one really knows

how many are sick.

"You can imagine

how desperate we are, since we're so

poor, and without a law to protect us. Here, if you have no money, the

government won't enforce the law. We really have very good laws in

Mexico, but a very bad government." Veronica Vasquez spoke these words

in the middle of a dusty street in Tijuana. "Companies come to

Mexico to make money. They think they can do anything they want with us

because we're Mexicans. Well, it's our country, even if we're poor. Not

theirs." "You can imagine

how desperate we are, since we're so

poor, and without a law to protect us. Here, if you have no money, the

government won't enforce the law. We really have very good laws in

Mexico, but a very bad government." Veronica Vasquez spoke these words

in the middle of a dusty street in Tijuana. "Companies come to

Mexico to make money. They think they can do anything they want with us

because we're Mexicans. Well, it's our country, even if we're poor. Not

theirs."

In Tijuana, most who die are working-age. Since

one-tenth of the city's 2.1 million residents work in over 900

maquiladoras, and even more are dependent on those factory jobs, the

spread of the virus among maquiladora workers is very threatening.

Alarm grew when two workers died in early April at

Plantronics, where 3,300 employees make phone headsets. Schneider

Electric closed when one worker died and 11 more got sick. Skyworks, a

manufacturer of parts for communications equipment with 5,500 workers,

admitted that some had been infected.

In the growing climate of fear, workers began to

stop

work. In Mexicali, Baja California's state capital, workers struck on

April 9 at three U.S.-owned factories: Eaton, Spectrum and LG.

Protesters said the companies were forcing people to come to work under

threat of being permanently fired, refusing to pay the

government-mandated wages

and failing to provide masks to workers. The factories were forced to

close by the state government.

Work then stopped at three more factories --

Jonathan,

SL and MTS. There, the companies offered bonuses of 20-40 per cent if

workers would stay on the job, but employees rejected the offer. One

striker, Daniel, told a reporter for the Mexican newspaper La

Jornada,

"We want health -- we don't want money, or bonuses or even double

pay. We just want them to comply with the presidential order that

nonessential factories close, and to pay us our full salary." Jonathan

makes metal rails for machine guns and tanks for U.S. companies.

Workers denied company claims that they made "essential"

telecommunications equipment, a common claim by factories that want to

stay

open.

The Organization of the Workers and Peoples, a

radical

group among maquiladora workers in Baja California, reported a week of

work stoppages at Skyworks, and a strike at Gulfstream on April 10. At

Honeywell Aerospace, workers began shutting down production on April 6.

"The company then laid off 100 people without pay, and fired

four of them," said Mexicali worker/activist Jesus Casillas. Honeywell

closed for a week, and then reopened.

As the strikes progressed, workers reported the

death of

two people in Clover Wireless's two plants that repair cellphones. They

were closed for one shift, and then started up again. Finally, on April

14, a general strike was called by Mexicali maquiladora workers, and

supported by the state chapter of the New Labor Center, a union

federation

organized by the Mexican Electrical Workers Union.

The Factories Don't Actually Close

Companies that said they were closing never really

did,

workers charged. "They'd close the front door and put a chain on,"

Casillas explained. "Then they bring workers in through the back door.

They'd call the workers down to the factory, and would tell them that

if they didn't go back to work, they'd lose their jobs permanently."

Elsewhere on the border, workers also complain

about

being forced to work. Company scofflaws even included breweries. In the

rest of Mexico, beer began to disappear from store shelves as a result

of López Obrador's order, shuttering breweries because

alcohol

production was not deemed "essential." Modelo and Heineken, two huge

producers, complied. Constellation Brands' two enormous breweries in

Coahuila, which make Corona and Modelo for the U.S. market, did not.

On May Day, a Facebook post even showed workers at

the

Piedras Negras glass plant that makes the bottles for Constellation

Brands lined up without masks. A message from a worker, Alejandro

Lopez, charges, "We ask for masks and they deny us, like they do with

[sanitizing] gel, which they only give us at the [brewery] entrance,

and that's

it." The response posted by the plant human relations director, Sofia

Bucio, says the company does everything required, and then goes on to

berate the worker: "We didn't go take you out of your house and force

you to work with us, right? If you don't like the measures IVC [the

glass company] is taking, the doors were wide open to let you in

when you came here, and they're the same to let you out."

In border cities across the Rio Grande from Texas,

other

factories that wanted to stay open said they'd let workers worried

about the virus stay home, but only at 50 per cent of their normal

wages. "People can't possibly live on that," charged Julia

Quiñones, director of the Border Women Workers Committee.

Since

López Obrador ordered a

raise a year ago, the minimum wage on the border has been 185.56 pesos

($7.63) per day. Fifty percent of that, in Nuevo Laredo, would barely

buy a gallon of milk (80 pesos).

"There's no other work the women can do in town,"

Quiñones explained. "In the past, some workers crossed the

border to earn extra money by donating blood. But the border is now

closed, even for those that have visas. They can't sell things in the

street because of the lockdown. The only option is to work."

One worker told her, "It is better to work at 100

per

cent, even if we're risking our lives, than to be at home with 50 per

cent."

Meanwhile, work stoppages spread to other border

cities,

as the death toll rose. Lear Corporation, which employs 24,000 people

making car seats in Ciudad Juárez, closed its 12 plants

there on

April 1. Lear had more COVID-19 fatalities than any company on the

border. It won't cite a number, and says it only learned of the first

death on April

3. By the end of April, however, 16 Lear workers were dead from the

virus, 13 from its Rio Bravo factory alone.

As other plants continued operations despite a

death

toll, strikes broke out. On April 17, workers struck at six

maquiladoras, demanding that the companies stop operations and pay

workers the government-mandated wages. Twenty people in the city had

died by then, including two workers at Regal Beloit (a coffin

manufacturer), and two

workers at Syncreon, according to protesters. At Honeywell, 70 strikers

said the company hadn't provided masks, and had forced people with

hypertension and diabetes to show up for work.

The Electrolux plant stopped work on April 24

after two

workers, Gregoria González and Sandra Perea, died. Two weeks

earlier, workers there had protested the lack of health protection.

When workers finally stopped working, the company locked them inside

and later fired 20. One told journalist Kau Sirenio, "The company

wouldn't tell us

anything though we all knew that we were working at the risk of getting

infected. They waited until two died before they closed, and fired

those who protested the lack of safe conditions. They still say their

operation is essential, but you can see how little they care about the

lives of the workers."

In Juárez, the mayor closed the city's

restaurants but allowed the maquiladoras to keep running. When workers

at TPI Composites began their protest, the city police were even called

out against them. Nevertheless, in Juárez and other border

cities throughout April, the pressure of workers did succeed often in

forcing the government to demand

compliance from the companies.

The U.S. Intervenes

At the end of April, the U.S. government

intervened on

behalf of the owners of the stalled plants. The Trump administration is

set on protecting the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement set to

go into effect on July 1. While the agreement has theoretical

protections for worker health and safety, there is no expectation that

it would be

invoked to ensure that plants remain shut until the COVID-19 danger

recedes. Instead, its purpose is to protect the chains of supply and

investment between Mexico and the U.S., especially involving factories

on the border.

López Obrador's order classified as

"essential"

only companies directly involved in critical industries such as health

care, food production or energy, and excluded companies that supply

materials to factories in those industries. But from the beginning,

many maquiladoras claimed they were "essential" anyway because they

supplied other

factories in the U.S. Luis Hernandez, an executive at a Tijuana

exporter association, admitted, "Companies have wanted to use the

‘essential' classifications of the U.S."

The military-industrial complex has a growing

stake in

border factories, which exported $1.3 billion in aerospace and armament

products to the U.S. in 2004, climbing to $9.6 billion last year. To

defend that huge stake, Luis Lizcano, general director of the Mexican

Federation of Aerospace Industries, told the Mexican government it had

to give

Mexico's defense industry the "essential" status it enjoys in the U.S.

and Canada.

Pentagon Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition

and

Sustainment Ellen Lord announced she was meeting Mexican Foreign

Minister Marcelo Ebrard to urge him to let U.S. defense corporations

restart production in their maquiladoras. "Mexico right now is somewhat

problematical for us, but we're working through our embassy," she said.

She later announced her visit had been successful.

Using the language of the Trump administration,

U.S.

Ambassador Christopher Landau played down the risk to workers. "There

is risk everywhere but we don't all stay at home out of fear that we're

going to crash our cars," he said in a tweet. "Economic destruction

also threatens health.... On both sides of the border, investment =

employment

= prosperity."

Finally, on April 28, Baja Governor Bonilla bowed

to the

pressure and ordered the reopening of 40 "closed" maquiladoras.

According to Secretary of Economic Development Mario Escobedo Carignan,

they are now considered part of the supply chain for essential

products. "We're not in the business of trying to suspend your

operations," he

told owners, "but to work with you to keep creating jobs and generating

wealth in this state."

Given that many "closed" factories in fact were

operating already, Julia Quiñones said bitterly, "This is

what

always happens here on the border. The companies break the law, and

then the law is changed to make it all legal." And Mexico's federal

government itself has begun to back down as well, announcing three days

after a U.S. request

that it will allow the many enormous auto plants in Mexico to restart

their assembly lines once automakers restart them north of the border.

The announcements didn't indicate that Mexico had

flattened the coronavirus infection curve or that the factories were

now safe. In one 24-hour period, from April 29 to 30, the number of

cases per million people went from 138 to 149. A million workers labour

in over 3,000 factories on the border. The virus has already led to

numerous deaths

among them, and if all factories resume production while it still

rages, the death toll will surely rise.

Luis Hernández Navarro, editor at

Mexico's

left-wing daily, La

Jornada (no relation to the Tijuana businessman),

reminded his readers that the catastrophic spread of the virus in Italy

was caused by the continued operation of factories in Lombardy until it

was too late.

"The maquiladora industry has never cared about

the

health of its operators, just its profits," he wrote recently. "Their

production lines must not stop, and in the best colonial tradition,

Uncle Sam has pressured Mexico to keep the assemblers operating . The

obstinacy of the maquiladoras makes it likely that the Italian case

will be repeated

here."

(To access articles

individually click on the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website:

www.cpcml.ca

Email: office@cpcml.ca

|