|

Supplement

No. 19May 30, 2020

Discussion of

Alternatives

The Need for a New Direction

for the Economy

• The Necessity for a Credible Public Authority

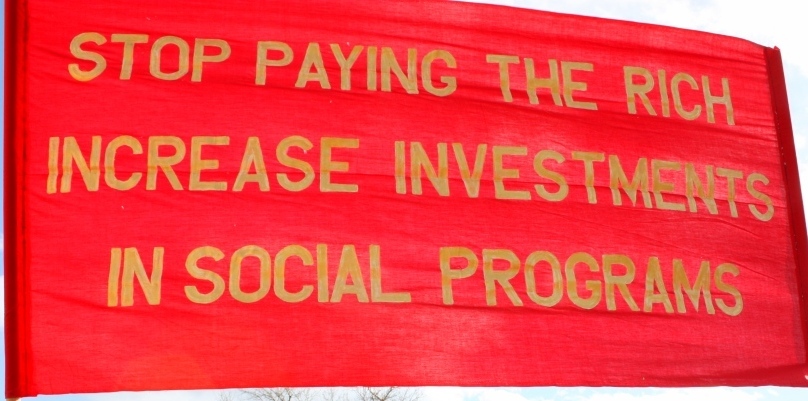

• Increase

Investments in Seniors' Care and Other Social Programs! Increase

the Value of the Capacity to Work of the Working Class!

- K.C. Adams -

• Time to End

Profit-Making in Seniors' Care (Excerpts)

- Canadian Centre for Policy

Alternatives -

Discussion of Alternatives

The pandemic has made it clear that a new direction is

needed in the care of seniors and the health care sector

generally. In order for that to happen, the most urgent need is

for a credible public authority.

1. A credible public authority is necessary

in order for the people to participate in setting the direction

for the economy. For a public authority to be credible,

legitimate and accountable in the modern era it must have a

direct connection with the working class. Having a direct

connection with the actual producers relates to the important

issue of who decides the direction of the economy. In the

seniors' care, health care and education sectors generally, a new

form is needed to lead them and their public enterprises. 1. A credible public authority is necessary

in order for the people to participate in setting the direction

for the economy. For a public authority to be credible,

legitimate and accountable in the modern era it must have a

direct connection with the working class. Having a direct

connection with the actual producers relates to the important

issue of who decides the direction of the economy. In the

seniors' care, health care and education sectors generally, a new

form is needed to lead them and their public enterprises.

A public authority consisting of elected members from the

seniors' care workforce, seniors themselves and

those concerned with their well-being is required. Such an

organization would be a victory resulting from the mobilization

of the workforce and activation of the human factor/social

consciousness.

Workers directly involved in the health care sector and

education sector for example, must have forms and mechanisms to

discuss, exchange views and decide the direction of the sectors

and the workings of the public enterprises they control and their

relations with other enterprises, sectors and the society and

economy as a whole.

New mechanisms must be created on the basis that there are those who are

charged with the social responsibility for the direction of the

sector and its public enterprises and budgets. Those put in

charge by the people would ascertain the amount of increased

investment needed to raise the level of care, and engage in

constant enforcement of regulations and compliance with them and

the rules regarding care and working conditions. All discussions,

decisions and reports of the public authority must be entirely

open and transparent and available on television, the Internet

and in written form.

2. Public seniors' care enterprises should be created that have

uniform high level care for all seniors, including those in long-term care

living facilities or receiving home care. No private profit should be

allowed in any aspect of health care and seniors' care that

receives any public money. This includes the creation of pharmaceutical and other health supply

public enterprises or the transformation of for-profit enterprises to public enterprises, if

they wish to continue to sell to the public sector. All

added-value from the production in public enterprises in the

health care and seniors' care sector should go back into improving

health care generally.

3. Public colleges should train seniors' care workers in all

aspects of care for seniors at the highest available level of

knowledge and practical experience and expertise. All those

wishing to work in the sector should be given free education and

a living stipend to take courses to prepare them for the work of

caring for seniors. The public colleges should be charged with

the responsibility of collecting information from workers in the

sector and from scientific studies on the highest level of care

for those in need. This is particularly important in dealing with

the issue of cognitive decline in seniors and how to combat

it.

4. Pay for seniors' care workers and their working conditions

should be at the highest level with no exceptions. The pay and

working conditions should be set and monitored by the unions and

collectives of health care workers, in discussion with the public

authority, ensuring they never fall below what is considered a

Canadian standard.

5. Family physicians refer seniors or even non-seniors, if the

need arises, for assessment for possible inclusion in long-term

and home care and the necessary level of that care. A collective

of professionals and other workers from the long-term care sector

should be responsible for the assessment and placement of

patients. The collective would aim to limit how long a patient must

wait for assessment and placement. This group could use its own

information and that of others in the sector on the needs of

the sector for additional beds and other resources, including

buildings and supplies. 5. Family physicians refer seniors or even non-seniors, if the

need arises, for assessment for possible inclusion in long-term

and home care and the necessary level of that care. A collective

of professionals and other workers from the long-term care sector

should be responsible for the assessment and placement of

patients. The collective would aim to limit how long a patient must

wait for assessment and placement. This group could use its own

information and that of others in the sector on the needs of

the sector for additional beds and other resources, including

buildings and supplies.

6. The value produced in the health care sector, including

seniors' care, should be fully accountable and realized (paid for)

in the broader economy and its enterprises. A price of production

for seniors' care and health care generally should be determined

through the use of a modern formula. The price of production for

health care, including seniors' care, in producing a healthy

working people and caring for them in retirement must be realized

(paid for) on a prorated basis by the public and private

enterprises in the economy over a certain size. The health care

payment should go directly to the public health care enterprises

established under the elected public authority of health care

workers and others and not through a government budget. The

budgets for the various public enterprises and sub-sectors within

the health care sector should be set by the workers themselves

and their collectives and verified through public discussion and

the elected health care public authority of the health care

workers and others. The money received should come to the public

enterprises through the provincial health care authority and not

through the provincial, federal or Quebec governments.

7. The regulations and rules governing the health care and

seniors' care sector and the working conditions should be set

through public discussion and agreed to by the elected public

authority, collectives of health care workers and individuals.

The public enterprises must be fully accountable for following

the agreed upon regulations and rules regarding the care of

seniors and working conditions and be transparent in reporting

any violations and remedies required. All public enterprises in

the health care and seniors' care sector must issue annual public

reports that detail their operations, plans and needs for the

coming year and foreseeable future, including increased

investments.

8. The increased investments needed for social programs should

be determined by the workers themselves and their public

authority in all the various sectors including, importantly, care

for seniors. The workers in every sector, their elected public

authority and unions should be responsible for determining any

increased investment needed, which would be in addition to the

realized value from the sector. 8. The increased investments needed for social programs should

be determined by the workers themselves and their public

authority in all the various sectors including, importantly, care

for seniors. The workers in every sector, their elected public

authority and unions should be responsible for determining any

increased investment needed, which would be in addition to the

realized value from the sector.

Any funds needed for increased investment beyond what the

sector and sub-sectors receive in realized added-value directly

from other enterprises in payment should be borrowed from a

public bank and not from private sources. The guarantee of return

of the loan for the increased investment comes from the potential

increased realized value arising from the expansion of the

service. Any loans must come from a public bank such as the Bank

of Canada or other newly formed public banks and not from private

sources. The issue of public banking must also be on the agenda

when discussing an alternative direction for the economy.

- K.C. Adams -

The crisis in long-term care homes has exposed the lack

of investment in social programs for the elderly necessary to

guarantee their well-being. The dire situation demands increased

investments in social programs directed at seniors but also in

health care and education generally. The aim is to guarantee the

right of all to the care and social programs the people require

in all phases of life, including in childhood before

entering the workforce and in old age.

The investment in care for the elderly is connected with the

value of the capacity to work under imperialism and the claim of

the working class on the value it produces, specifically social

reproduced-value. The imperialist oligarchy deprives the working

class of its rightful claim for social reproduced-value as the

claim exists in contradiction with the expropriation of new value

as private profit.

Improving the lives of the retired means the economic value of

the capacity to work of the working class as a whole becomes

greater. The improvement in the quality of life when retired

increases the claim of the working class on the value it produces

thus reducing the amount of new value the imperialist oligarchy

can expropriate. Improving the lives of the retired means the economic value of

the capacity to work of the working class as a whole becomes

greater. The improvement in the quality of life when retired

increases the claim of the working class on the value it produces

thus reducing the amount of new value the imperialist oligarchy

can expropriate.

The imperialist oligarchy stands opposed to any improvement in

the economic value of the capacity to work of the working class

that is not necessary within the imperialist economy. The

oligarchs seek to cheapen all social programs that do not improve

the employability of the working class while finding ways to

organize those that do, such as education, in a way that does not

reduce their expropriation of added-value for private profit or

damage their war economy.

The imperialists face a dilemma. They need educated and

healthy workers but any improvement means an increase in the

value of workers' capacity to work. How to solve the dilemma has

been an aspect of why public and semi-public social programs came

into being.

The imperialist oligarchs have created semi-public education

and health care as means to lessen the burden of paying for them

on the oligarchs as a whole yet make educated and healthy workers

available for employment. This does not mean that those who work

in public and semi-public education and health care do not

produce as much new value as if they were working in completely

privatized enterprises of the same level. The public and

semi-public social programs hold two advantages for the oligarchs

as a whole: the full price of production to educate and look

after the health of workers is not paid by the oligarchs as the

funding comes from taxes of which the biggest companies pay very

little, and the oligarchs do not have to realize (buy) directly

the higher value of the capacity to work as it is reduced by the

amount of added-value the public social programs do not

expropriate.

Public workers in most social programs in public and

semi-public enterprises produce enormous new value of which they

claim a portion as reproduced-value. Wages are the individual

portion of the reproduced-value and social programs are the

social portion. The working class claims the individual and

social reproduced-value as its portion of the new value it

produces while those who buy their capacity to work expropriate

the rest as added-value or profit. The trick with public social

programs is that the added-value or profit is not directly

expropriated but transferred indirectly to the imperialists who

buy the capacity to work of educated and healthy workers, at

least part of it.

Public and Semi-Public Enterprises

The imperialist oligarchy as a whole does not pay the full

price of production for what workers produce in public and

semi-public enterprises. They skirt this economic responsibility

by hiding behind general taxes as the form of revenue needed to

fund most social programs. Working people and small and

medium-sized businesses pay the vast majority of taxes to realize

the value from public and semi-public enterprises while big

business mostly avoids paying anything.

By not paying directly the full price of production for what

public workers produce and mostly avoiding taxes, the ruling

imperialist elite and their global private enterprises

expropriate indirectly the added-value portion of the new value

public workers produce through social programs and the public and

semi-public enterprises.

This added-value exists as the capacity to work of educated

and healthy workers or as cheap fixed infrastructure such as

bridges, roads, mass transit etc and socially produced

circulating value such as electricity or postal services, which

the oligarchs buy at "preferred industrial rates."

The imperialist oligarchs receive the full value from publicly

produced infrastructure and social programs and the increased

value of the capacity to work of the workers they employ but do

not fully pay the price of production for the infrastructure or

the socially produced portion of the capacity to work of the

working class. The difference between the price of production and

what the imperialists and their enterprises pay and what they

should pay is expropriated as indirect private profit.

Expropriation of Added-Value from Programs to Care for the

Elderly

Workers in public social programs to care for the elderly

produce new value, which includes the reproduced-value they claim

as wages, benefits and social programs, and the added-value the

oligarchs expropriate indirectly as profit. The public and

not-for-profit long-term care homes pass on much of the

added-value workers produce to the general economy where both

public and private enterprises expropriate it as indirect profit.

This occurs indirectly because the public and private enterprises

in the economy do not directly pay the price of production

arising from the work-time involved in caring for the elderly.

The social reproduced-value of seniors' care forms part of the

aggregate value of the capacity to work of the working class.

Within the social relation between the working class and the

not-working class that buys its capacity to work, the working

class is available to work and the not-working class is supposed

to pay the full individual and social value of workers' capacity

to work, which includes seniors' care.

Privatization of Social Programs

When a social program is privatized, which is the case with

the numerous privately owned long-term care homes and home care,

the individual owner of the privatized service expropriates as

added-value or private profit a portion of the new value workers

produce. This means the full price of production for the

privatized social program must be realized. The government

generally pays the majority of the price of production while the

elderly and their families pay the rest as user fees.

Privatization of social programs has the effect of indirectly

reducing the amount of added-value or profit the imperialist

oligarchy as a whole expropriates from social programs at least

those that do not directly profit from privatized social

programs. It also increases the price of production if the level

of the social programs is maintained as before the government did

not pay for the added-value, which is now expropriated by the

private owner. The full amount of the price of production must be

directly paid to the owners of the privatized social programs,

which the government pays. The fact that the full price of

production for the privatized social programs must be paid has

the effect of concentrating the expropriated added-value in a few

hands while depriving the rest of the imperialist oligarchs from

indirectly receiving any of the value.

The oligarchs in control, which do not profit directly from

privatized social programs accept the privatized situation

because the imperialists that have intruded on social programs

are extremely powerful but also they can force a reduction in the

value of the privatized social programs to reduce the amount of

social reproduced-value the working class can claim. According to

the many recent reports of how bad the situation has become in

many long-term care homes and in home care, the level of care has

been drastically reduced. A similar situation exists in public

education, which is facing a lowering of quality such as

increased class sizes and other issues. The oligarchs in control, which do not profit directly from

privatized social programs accept the privatized situation

because the imperialists that have intruded on social programs

are extremely powerful but also they can force a reduction in the

value of the privatized social programs to reduce the amount of

social reproduced-value the working class can claim. According to

the many recent reports of how bad the situation has become in

many long-term care homes and in home care, the level of care has

been drastically reduced. A similar situation exists in public

education, which is facing a lowering of quality such as

increased class sizes and other issues.

Faced with the situation, the imperialist oligarchy can and

does call for the elimination of privatization as an option and

to revert to public or semi-public delivery of social programs. Up

to this point in the imperialist world, including Canada, the

working class has not intervened forcefully with its own view and

outlook but has been led to discuss only the options the ruling

oligarchs have presented regarding the direction of social

programs. This is a situation the organized working class must

change.

In BC, almost all the money to pay for privatized long-term

care homes and home care comes from the government. The

individual owners of the privatized service, through their private

enterprises, directly expropriate added-value from the new value

their workers produce. In this situation of privatized long-term

care homes and home care, in contrast with the previous situation

of public enterprise, either the level of service must go down or

the government must now pay more for the service as the

individual owners expropriate the added-value directly. If the

service is kept at the same level and the individual owners

directly expropriate added-value as private profit, this means the

price of production of the service is fully paid mostly by the

government and none of the added-value workers produce flows to

those imperialist oligarchs not directly involved in delivering

the privatized social programs.

The privatized social program at the same level of service

means the government pays more, as the full price of production

is required because the individual owner of the privatized

service expropriates profit. This in fact leaves less public

money available for other programs while putting pressure on the

government to increase taxes.

In contrast, a publicly-owned long-term care home or home care

does not directly expropriate the added-value. At the same level

of service, the price paid by the government is lower and the

added-value from the service flows into the general economy

mainly as part of the value of the capacity to work of the

working class that is not paid. This phenomenon explains in part

why the imperialist oligarchs created public and semi-public

education, health care and other social programs in the first

place. They needed more educated and healthy workers and public

social programs appeared as the best option on a mass scale.

However, productive forces develop and change, for example the

introduction of computers and the Internet, and the tendency of

parasitism and decay is ever-present, seizing greater parts of the

imperialist economy. Powerful new imperialist cartels, which

appear as global funds, roam the world seeking out places to

invest, such as social programs and public infrastructure. In

addition, new global cartels of immense social wealth -- such as

Microsoft, Sodexo, Aramark and Compass Group -- have

directly invaded public and semi-public enterprises, even prisons in

the United States. Waste Management and other green imperialist

monopolies have grown to challenge public delivery of social

programs, such as city waste removal, and want to expropriate as

their own the added-value that workers in the social service

sector produce. They do not want to have it flow to the collective of

imperialists and their enterprises, which have hitherto

indirectly profited from social programs and their production of

the capacity to work of the working class for which they have not

paid. The imperialists privatizing social programs and

infrastructure want governments to pay the full price of

production to them for the privatized social programs, even if

this means higher taxes or less public money for other programs --

unless investments in social programs are lowered, which in fact

has occurred. However, the privatized services face pushback from

others in the imperialist oligarchy who want to organize social

programs differently so that they can expropriate the social

product indirectly and also quell any uproar from the working

class.

The Office of the Seniors' Advocate in BC, in a report dealing

with the operations of long-term care homes entitled A Billion

Reasons to Care, found that usually the level of care goes

down when privatized, if funding is kept the same as before. To

bring the level of privatized service up to where it was before

privatization requires more government funding. The increased

money must come from the aggregate new value the working class

produces, usually as new taxes on them or on small and medium-sized companies or from government borrowing from private

lenders, which has become a lucrative source of guaranteed

profit.

However, increased funding for privatized social programs

usually means more added-value as expropriated private profit by

the enterprises involved, and does not allow any added-value to

flow indirectly to the imperialist oligarchy as a whole, and can

also mean a degrading of the overall health and education of the

working class and its employability. In Canada and the U.S., this

has been papered over with large numbers of educated immigrants

coming into the workforce, stolen for nothing from developing

countries.

At any rate, a dispute exists within the ruling elite over

privatization of public services, with many opposing such a move

as it means profit from the social programs goes to particular

owners of the service rather than to the imperialist oligarchy as

a whole. Generally, the working class is a spectator to this

debate, either for or against privatization of public services, and

does not forcefully present its own views or an alternative that

favours working people.

Within the dispute whether to have social programs delivered

as fully public enterprises, not-for-profit charity enterprises,

or private enterprises, the subject is rarely broached as one of

guaranteeing the rights of all to health care, education and a

cultured standard of living and care for the elderly at the

highest level the productive forces can deliver. The dispute

generally circulates around the issue of "cost" to the

imperialist oligarchy and who profits and how best to keep

spending on the working class as low as possible so that the

price of their capacity to work is likewise as low as possible,

expropriated private profit remains as high as possible, and yet the

working class and its capacity to work remains available at an

appropriate level.

How to Pay for Social Programs

To function, a modern economy and society need a high level of

social programs. It is important to discuss the issue of realizing (paying for) the value

workers produce in those programs and to

formulate a pro-social alternative that favours the people.

The working class has to break out of the anti-social

discussion of the ruling oligarchs. It must force through its view for

increased investments in social programs and that the socialized

economy as a whole, which includes all its individual

enterprises, must pay the full price of production for the

capacity to work of the aggregate healthy and educated working

class and its reproduction and existence from birth to passing

away at the highest possible level given the existing productive

forces. The working class as a whole is always available to work

so its reproduction and existence and rights from birth to

passing away must be guaranteed.

History has shown that the right to health care and education

and care for the elderly cannot be guaranteed outside of public

enterprises and with the economy and its enterprises directly

paying for the produced value of social programs. Using public

enterprises to solve the problem cannot be separated from the

issue of increasing investments in social programs to bring them

up to a cultured and sustainable standard for all and forcing the

other parts of the economy and enterprises to pay the full price

of production of the capacity to work of the working class. This

would increase the aggregate value of the capacity to work of the

working class and the amount it can claim on the value it

produces, the reproduced-value. History has shown that the right to health care and education

and care for the elderly cannot be guaranteed outside of public

enterprises and with the economy and its enterprises directly

paying for the produced value of social programs. Using public

enterprises to solve the problem cannot be separated from the

issue of increasing investments in social programs to bring them

up to a cultured and sustainable standard for all and forcing the

other parts of the economy and enterprises to pay the full price

of production of the capacity to work of the working class. This

would increase the aggregate value of the capacity to work of the

working class and the amount it can claim on the value it

produces, the reproduced-value.

The mechanics of how to pay for the full value of the social

programs that increase the value of the capacity to work of the

working class from the value workers produce in the economy can

be worked out on a prorated basis for each enterprise; that is

not a problem. The problem is how to organize this and enforce

it. What new alternative forms and mechanisms are necessary for

the working class to realize its rights and to decide these

matters, such as the standard of living of workers generally, and

to enforce compliance with them? Forcing the imperialist

oligarchy to agree to such a necessity to guarantee the rights of

all working people is the order of the day and task of the

organized working class. This requires a broad front of struggle

to increase investments in social programs and raise the quality

of life of the working class and guarantee the rights of all,

including importantly the rights of seniors and children. How to

accomplish this in practice with new forms needs to be discussed

and concretized. It can be done!

- Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives -

Excerpts from the report by Andrew Longhurst and Kendra

Strauss writing for the Canadian Centre for Policy

Alternatives.

The coronavirus pandemic has shone a light on serious problems

in Canada's seniors' care system, as nursing homes quickly became

the epicenters of the outbreak. These problems are not only due

to the greater vulnerability of seniors to the disease, but also

to how care is organized and staffed.

[...]

How did these vulnerabilities in eldercare come about? Going

into the crisis, our system has been weakened by policy decisions

beginning in the early 2000s that:

- Reduced access and eligibility to publicly funded care;

-

Produced vulnerabilities and gaps that are impacting seniors and

those who care for them; and,

- Encouraged profit-making

through risky business practices such as subcontracting, which

undermined working conditions and created staffing shortages.

A System Already Under Stress

Long-term care facilities (LTCF) are at the centre of COVID-19

outbreaks in BC and beyond. In our province (BC) about two thirds

of long-term care is delivered by non-profit organizations and

for-profit companies, with the remainder provided directly by

health authorities. The most severe and widely reported outbreak

has been at the Lynn Valley Care Centre in North Vancouver.... In

a recent CBC report on conditions at the Lynn Valley Care Centre,

Jason Proctor wrote:

In interviews with CBC News, family members, health-care

professionals and community members spoke about the march of a

virus that has moved through the facility in much the same way it

has through the world, preying on vulnerabilities that seem

obvious in hindsight: Reliance on a subcontracted labour force

whose members... work multiple jobs to make ends meet. Gaps in

communication. A societal reluctance to talk about the basics of

hygiene.

Sub-contracting is also identified by the Globe & Mail

in their investigation of how COVID-19 spread at the Lynn Valley

Care Home. Sub-contracting seniors' care occurs when service

providers (e.g., home support agencies, LTCFs, assisted living

facilities) contracted by regional Health Authorities to provide

care then sub-contract with other companies for services such as

direct care, cleaning, cooking or maintenance. Contracts are

often awarded on the basis of lowest cost, which translates into

lower wages, poorer benefits and fewer full-time positions.

Long-Term Care Facilities (LTCFs) Are at the Centre of

Covid-19 Outbreaks in BC and Beyond

The prevalence of sub-contracting in the eldercare sector is

no accident. In 2002 and 2003, the BC government introduced Bill

29 and Bill 94, which stripped no-contracting out and job

security clauses from the collective agreements of health care

workers and resulted in more than 8,000 job losses by the end of

2004. Together, these laws (which were repealed in 2018) provided

health sector employers, including private LTCFs, with

unprecedented rights to layoff unionized staff and hire them back

as non-union workers through subcontracted companies. Bill 37

also followed in 2004, which imposed wage roll-backs on more than

43,000 health care workers.

The results were predictable. As CCPA research has

demonstrated, policies and legislation enacted during this period

negatively impacted wages and working conditions while also

reducing funding and access to services.

A lack of successor rights for unionized workers meant that

subcontracting (often called "contract-flipping") was used to

make union organizing more difficult. For example, the number of

unionized community health workers (three quarters of whom work

for home support agencies) declined almost 10% between 2008 and

2011, before increasing by about 2.5% from 2008 levels by 2013.

The number of unionized care aides declined by over 5% between

2008 and 2011, before increasing again slightly by 2013 (for an

overall decline of 3.8% between 2008-2013).

Reduced funding for, and access to, publicly funded seniors'

care from the early 2000s resulted in the rationing of care.

Rationing means that access to publicly funded care is limited to

those with more acute needs, leaving seniors with less complex

needs without access to supports that might prevent deterioration

and keep them from needing institutional care. For example, data

show that among those aged 65+ who were assessed by Vancouver

Coastal Health for long-term care intake between 2011/12 and

2015/16, the proportion of seniors requiring extensive or more

physical assistance rose from 49.6% to 54.6%, and moderate to

severe cognitive impairment increased from 52.1% to 57.1%. So as

staffing levels have declined, the care needs of many residents

have increased.

Reduced funding for, and access to, publicly funded seniors'

care from the early 2000s resulted in the rationing of care.

At the same time, more of those publicly funded services are

being delivered by for-profit companies, often in LTCFs that

combine publicly funded and private-pay beds. As a recent report

by the BC Seniors Advocate highlighted, prior to 1999, 23% of

beds were run by for-profit companies; by 2019 it was 34% of

beds. Health authorities pay for the services provided by LTCFs

through block funding which accounts for the direct care hours

that each resident is to receive (currently a provincial

guideline of 3.36 hours per resident per day) and the cost of

other services and supplies such as meals. There are no

restrictions on how operators spend these dollars and health

authorities do not perform payroll or expense audits to ensure

public funds are actually spent on direct care.

Shockingly, the Seniors Advocate's report found that:

- Most direct care (67%) is delivered by care aides, the

lowest paid care workers. Health authorities calculate the costs

of care on the basis of the master collective agreement, which

covers unionized direct care workers. Yet, LTCFs and their

sub-contracted companies are not required to pay the rates set

out in that agreement. The report states that: "In 2017/18, the

industry standard base wage rate for a care aide was $23.48/hour.

Some care aides were paid as much as 28% less based on the lowest

confirmed wage rate of $16.85/hour, which was found in a

for-profit care home". In other words, care companies make

profits by underpaying the workers who provide the majority of

direct care despite receiving funding based on the assumption

they pay union rates contained in the master collective agreement

(industry standard).

- Operators are not monitored to ensure that they are

providing the number of care hours they are being paid for.

Without adequate oversight and reporting, companies thus also

make profits by understaffing, which impacts the amount and

quality of care that residents receive.

- Many LTCFs have a combination of publicly-subsidized and

private-pay beds. But the co-located private-pay beds are not

consistently included in these facilities' calculation of

delivered care hours. As a result, publicly funded care hours may

be used to cross-subsidize the care of private-pay residents who

pay out-of-pocket, allowing greater profit-taking from

private-pay beds and exacerbating staffing shortages as companies

use the same staff to cover both publicly funded and private-pay

beds (when private-pay beds should have their own staff

complement).

- While receiving, on average, the same level of public

funding, contracted non-profit LTCF operators spend $10,000 or

24% more per year on care for each resident compared to

for-profit providers. In just a one-year period (2017/18),

for-profit LTCFs failed to deliver 207,000 funded direct care

hours, whereas non-profit LTCFs exceeded direct care hour targets

by delivering an additional 80,000 hours of direct care beyond

what they were publicly funded to deliver.

These are significant issues in their own right. Care workers

are being underpaid relative to the funding that operators

receive. But even if we are unconcerned about fairness, low

staffing levels are not conducive to quality care.

Data from the 2013 Statistics Canada Long-Term Care

Facilities Survey showed that although for-profit companies

outnumbered public and non-profit providers in the survey, they

reported spending less on care aides, licensed practical nurses

and other health care staff, and less on dietary, housekeeping

and maintenance workers. Low staffing places both workers and

residents under increased stress and reduces the time carers have

with residents. And as the BC Seniors Advocate report points out,

low pay and understaffing are a vicious circle -- they make it

difficult to recruit and retain staff, while operators that

employ staff directly (no subcontracting) and pay higher wages do

not experience the same kinds of shortages.

We need only look to the four LTCFs that are part of the

Retirement Concepts chain (owned by the Chinese company Dajia

Insurance, the successor company of Anbang Insurance Group) to

see these dynamics at work. Regional health authorities in recent

months have taken over management of these four Retirement

Concepts facilities and brought in their own nursing staff due to

persistent shortages that were compromising resident care and

safety.

A key reason for staffing challenges is that many LTCF staff,

namely care aides, must work more than one job in order to make

ends meet. While the provincial government committed to review

contracting and sub-contracting in the sector after the crisis,

the newly-announced single-site order, increasing wages to the

industry standard, and guaranteed full-time hours at one site are

as-yet only guaranteed for six months.

Risks Associated with For-Profit Ownership and

Financialized Corporate Chains

A large body of academic research demonstrates that staffing

levels and staffing mix are key predictors of resident health

outcomes and care quality, and that care provided in for-profit

long-term care facilities is generally inferior to that provided

by public and non-profit-owned facilities. High staff turnover,

which is linked to lower wages and the heavy workloads demanded

by inadequate staffing levels, is associated with lower-quality

care in large for-profit facilities.

The BC government's longstanding reliance on attracting

private capital into the seniors' care sector has benefited

corporate chains with the ability to finance and build new

facilities. Between 2009/10 to 2017/18, BC only invested $37.4

million in LTCF infrastructure, and $3.3 million in assisted

living infrastructure, representing on average 0.5% and 0.04%,

respectively, of total health sector capital spending over this

period. In other words, not much at all.

By 2016, corporate chains controlled 34% of all publicly

subsidized and private-pay long-term care and assisted living

spaces in BC while 66% of units were owned by either non-profit

agencies or health authorities.

Another way to look at the significance of corporate chains is

by looking at the top 10 largest corporate chains by market share

-- i.e., the share of the total publicly subsidized and

private-pay units in BC controlled by the top 10 chains. Over

one-quarter (27%) of all assisted living and long-term care units

in BC were controlled by the top 10 corporate chains collectively

(as of 2016). Among contracted operators, Retirement Concepts

(owned by Anbang/Dajia Insurance) controls the greatest share of

assisted living and long-term care units in BC. It has 2,158

units or 7.8% market share of publicly subsidized and private-pay

units in BC -- more than double the number of units held by the

second-largest chain.

Corporate chains pose risks to quality of care. While the

growth of chains has received less attention in the health

services research in Canada, a prominent U.S. study found that

"the top 10 for-profit chains received 36 per cent higher

deficiencies and 41 per cent higher serious deficiencies than

government facilities, [with] [o]ther for-profit facilities also

[having] lower staffing and higher deficiencies than government

facilities." Studies show that staffing levels -- a key predictor

of care quality -- were already falling before the takeover by

private equity investors. Another U.S. study found that there

were no significant changes in staffing levels following private

equity purchase "in part because staffing levels in large chains

were already lower than staffing in other ownership groups."

Corporate chain consolidation in seniors' care is a reflection

of financialization in the health care and housing

sectors. Financialization occurs when traditionally non-financial

firms become dominated by, or increasingly engage in, practices

that have been common to the financial sector. Globally, there is

growing interest among investors in seniors' care because the

business is real estate focused. Seniors' care facilities are

increasingly being treated as financial commodities that are

attractive to global capital markets.

International experience -- and the unfolding Retirement

Concepts story in BC -- tells us that financialized care chains

tend to employ risky business practices. Chains are typically

bought and sold frequently using debt-leveraged buyouts,

inflating asset sales prices and leaving the chains loaded with

ever more debt until the cash flow -- dependent on government

funding -- cannot meet the debt-servicing costs. This situation

can result in financial crisis, bankruptcy, and chain failure.

The United Kingdom's largest care chain -- Southern Cross --

collapsed in 2011 as a result of these risky financial practices

and successive flips of the real estate assets to different

investors. Southern Cross's collapse created months of

uncertainty for 31,000 residents and their families -- as well as

for 44,000 employees -- until other buyers could be lined up.

The financialized business model is often structured around

short-term real estate flipping where government and taxpayers

assume the financial risk of failure. The disruption that can

result from these business practices undermines the conditions

necessary for stable "relational care" in which continuity in

staff allows care workers to know their residents and the rest of

the staff. The opposite of relational care is high staff turnover

and workforce instability, which can have a negative effect on

quality. This has been occurring at the four Retirement Concepts

facilities that were put under health authority

administration.

Rebuilding Seniors' Care in BC

The COVID-19 crisis is exposing the long-term impacts of

policies aimed at cutting costs and expanding the role of

for-profit companies in the seniors' care sector in BC. Reduced

pay and benefits and understaffing are bad for workers; they are

also bad for vulnerable older people who depend on those workers

to meet their daily needs. The COVID-19 pandemic may be

unprecedented in recent times, but its impacts are being felt in

LCTFs because of the way seniors' care has been undervalued,

underfunded, and privatized.

Policy can be steered in a different direction, however.

Over the medium and long-term, the BC government should end

its reliance on contracting with for-profit companies and

transition exclusively to non-profit and public delivery of

seniors' care.

The evidence is in: profit-making does not belong in seniors'

care. The revelation from the Seniors Advocate that contracted

for-profit LCTFs failed to deliver funded direct care hours

should be reason enough to determine that the government is

getting poor value for money by contracting with corporations.

Public dollars are flowing into profits, not into frontline care

as earmarked.

Moreover, the single-site public health order is largely a

response to the erosion of wages and working conditions in

long-term care that began in the early 2000s. In mere weeks, the

BC government is trying to rectify workforce instabilities

brought about over years of labour policy deregulation and

business practices intended to drive profits. These policy

decisions were championed by care companies and corporate chains.

And once the current crisis is over, we simply cannot return to

the status quo.

The BC government needs to move boldly on a capital plan to

start building new seniors' care infrastructure and acquiring

for-profit-owned facilities. BC's longstanding policy approach

has allowed corporations and their investors to build up large

real estate portfolios on the public dime, while receiving

generous public funding that assumes they are paying unionized

wages when many in fact are not.

The BC government said that it will cost about $10 million per

month to provide "top-up" funding to increase wages to the

unionized industry standard so that no worker loses income as a

result of the single-site order. It appears these public dollars

will flow to employers that, up to now, have not been paying the

unionized industry standard rate. Structuring the wage top-up in

this manner raises some concerns.

The top-up will go to some employers who are already funded to

pay the unionized rate. As noted above, the Seniors Advocate

found that a significant number of long-term care operators have

been funded using a formula that is based on the unionized

industry standard rate but have failed to pay their workers

commensurately. In practice, the top-up means these operators

will be rewarded for over-charging the public. Instead, they

should be compelled to pay the unionized wage rate -- without

additional funding -- and to become part of the public sector

labour relations structure (as was required of all publicly

funded operators before the early 2000s).

Topping up operators who have underpaid their workers is not a

cost-effective strategy now or beyond the current pandemic. But

neither is it tenable to suggest that these workers will get a

pay cut after the pandemic, or that they should return to

cobbling together an income through multiple part-time jobs. All

of which reinforces the need to move to consistent public and

non-profit ownership and delivery of care.

In the immediate term, there are a number of steps that the

provincial government should take:

- First, require much greater transparency, public reporting

and accountability in the seniors' care sector. This should

include implementation of the Seniors Advocate's recommendation

that public funding for direct care in contracted LTCFs must be

spent on direct care only, and to require standardized reporting

in all LTCFs (including public disclosure of audited revenues and

expenditures). These recommendations align with a recent CCPA-BC

report that looks at the growth of private for-profit seniors

care. Over the longer term, moving exclusively to non-profit and

public delivery of seniors' care addresses this problem. Public

institutions and non-profits don't have investors; any excess

revenue is reinvested into frontline care.

- Second, ban sub-contracting. The BC government rightly

repealed Bills 29 and 94 in 2018, but subcontracting continues to

undermine employment standards that are preconditions for quality

care. COVID-19 has made this very clear. The industry-wide labour

relations and bargaining model, established in the 1990s,

provided standardized wages and working conditions. This

structure needs to be put back together and, following the end of

special COVID-19 measures, existing operators should be part of

the public-sector master collective agreements if they are

receiving public funding. This was the case before the early

2000s.

- Third, in the assisted living sector, seniors in both

publicly subsidized and private-pay units need much greater

protections regarding tenancies, rents and fees as the incomes of

seniors and their families may decline significantly during the

pandemic. We know from CCPA research and CMHC data that assisted

living costs continue to rise faster than the incomes of many

low- and middle-income seniors.

- Fourth, public funds should not be used to bail out

over-leveraged corporations in the seniors' care sector. The

impact of COVID-19 on international financial markets will likely

have knock-on effects and the provincial government should be

prepared for the possible financial collapse of for-profit LTCFs.

It should be prepared to take over these facilities and

chains.

When we emerge from this crisis, there should be a public

consultation on the kind of seniors' care system we want in our

province and across Canada, drawing on lessons from the pandemic.

This should inform a comprehensive planning approach to

projecting demand and identifying appropriate transitions for

seniors across the continuum of home and community based

services.

This crisis is highlighting how the exclusion of seniors' care

from Canada's universal Medicare system, and the inconsistencies

across and within the provinces, lead to uneven conditions for

seniors, their families and workers. This unevenness creates the

vulnerabilities that we are seeing now, and the disproportionate

impacts on older people in care and those struggling to look

after them.

We have the evidence and tools to rebuild seniors' care.

COVID-19 has revealed the urgency of doing so.

Note

1. The provincial government also recently announced that the BC

Care Providers Association, a long-term care industry group --

will receive $10 million to administer an infection control

program for LTCFs. Public dollars for a government program should

be disbursed by government, not by private industry.

(To access articles individually click on

the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|