|

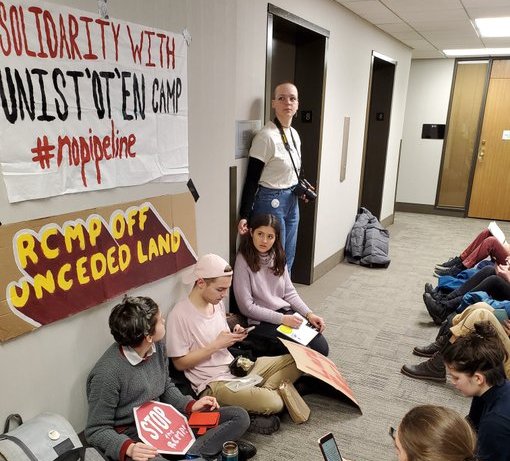

February 8, 2020 - No. 3 Condemn the Violence of the

• Canada-Wide

Actions Stand with the Wet'suwet'en - Union of BC Indian Chiefs - • Court

Challenge

Filed Against Coastal GasLink - Wet'suwet'en Hereditary

Chiefs - • Invasion 29th Annual Women's Memorial Marches on February 14 • Justice

for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and

Girls!

The Damage Caused to

Canadians and the Economy • Predatory Expansion of Software Platforms • Highlights

of

Statistics Canada Report Measuring Workers - K.C. Adams -

• Workers' Capacity to Work and the Contradiction between Its Exchange-Value and Use-Value

Stand With the Wet'suwet'en! Condemn the Violence of the

|

|

|

Women's Memorial Marches are taking place on Valentine's Day in cities and towns across the country, demanding justice for all the Indigenous women and girls who have been murdered or gone missing. The first march was held in 1992 in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, to call for action after the murder of a Coast Salish woman was met with indifference by the authorities and media.

Through

initiatives like the annual February 14 marches,

Indigenous women continue to demand Justice for

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls.

In this regard, Indigenous women have militantly

affirmed that it is the voices of the people which

must prevail when it comes to defining what

constitutes justice.

Through

initiatives like the annual February 14 marches,

Indigenous women continue to demand Justice for

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls.

In this regard, Indigenous women have militantly

affirmed that it is the voices of the people which

must prevail when it comes to defining what

constitutes justice.

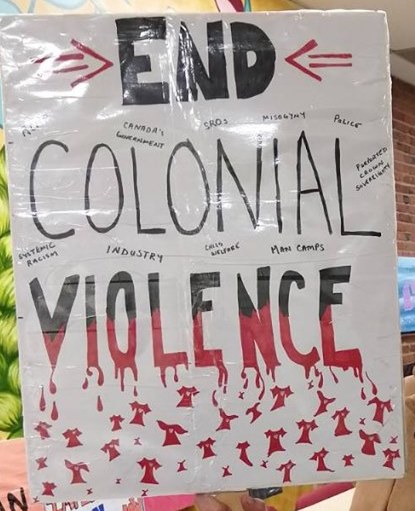

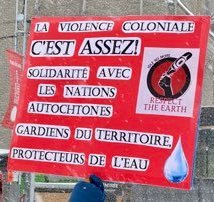

This year's memorial marches are taking place at

a time when Indigenous peoples are militantly

defending their right to be against the violation

of their sovereignty and violent attacks on the

land defenders. The Liberal government and

instruments of the state including the police and

courts are imposing Canadian rule of law on

Indigenous territory where it has no authority, in

an attempt to negate the title and rights of the

Indigenous nations. The Trudeau government

continues to assert that the colonial framework

with its "rule of law" in the service of private

corporate interests must prevail. It has no

intention of recognizing the hereditary and

inherent rights of the Indigenous peoples which

belong to them as the first inhabitants of Turtle

Island.

This is also the first February 14 since the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls delivered its report. The Report concluded, based on the evidence it gathered, that missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls were the victims of a Canadian genocide, namely a concerted campaign to extinguish the Indigenous peoples, their history, culture and way of life. The Introduction to the Report said: "This genocide has been empowered by colonial structures evidenced notably by the Indian Act, the Sixties Scoop, residential schools and breaches of human and Indigenous rights, leading directly to the current increased rates of violence, death and suicide in Indigenous populations."

The response to the Report from the Trudeau government was to promise a "thorough review" and "national action plan." What this means is that the government will not give up the prerogative powers usurped by the Crown and establish nation-to-nation relations. Nor will it provide redress for all the crimes committed against the people and put in place the conditions required for the Indigenous peoples to exercise their right to be. The criminalization of the Wet'suwet'en for defending their sovereignty over their unceded territory shows where the Trudeau and Horgan governments stand.

Colonial relations, including the Indian Act, imposed a patriarchal system on Indigenous nations. Women were deprived of their place of honour and respect within the family and their important role in governance. Women became "fair game," a status which the courts, police and other state institutions continue to impose. Violence against Indigenous women and girls, both on and off reserve, is a consequence of these ongoing colonial relations and the decision-making process imposed on the Indigenous peoples to this day, which are the tools of genocide. At the heart of the matter is the fact that the Indigenous peoples are not seen as human beings with specific rights and needs, and with whom the Canadian state has definite nation-to-nation relations defined through treaties as well as international law. They are seen as impediments to the decisions made by private interests, and the real aim of the government is to extinguish rights, not uphold them.

TML Weekly pays its deepest respects to the families and loved ones of the murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls on the occasion of the February 14 marches. The persistence of Indigenous women and peoples to affirm their right to be is an inspiration to all, especially their insistence that they will define what they need and not allow others to tell them what is acceptable. We call on Canadians to provide them with their full support, including discussing this situation with their peers and participating in the marches.

The Damage Caused to Canadians and the Economy by Precarious Work

Predatory Expansion of Software Platforms

Foodora couriers carry banner in the Toronto

Labour Day parade, September 2, 2019.

The supranational financial oligarchy has launched an expansion in Canada to tighten its grip on the economy. The oligarchs are using software platforms to target urban passenger transportation, the delivery of freight and prepared restaurant food, hotel, home and business cleaning and renovation, construction and the trafficking of contract workers to all manner of public and private employers.

The aim of the financial oligarchy, as always, is not to use the advances in scientific technique to favour the working people and society, humanize the social and natural environment and bring enlightened planning to urban and rural life but to expand their private control of the economy, compete and defeat their rivals and maximize their private profit. The software platforms and applications on smartphones turn the working class into "Workers-on-Demand" or gig workers, without rights, in precarious employment and with below-standard wages, benefits and working conditions.

To launch

their expansions into new cities, the

supranational ride hailing companies attempt to

gain favourable public opinion from users of their

apps through repeated exposures in the mass media

of the chaos, anarchy and shortcomings of urban

mass transit and in particular the taxi industry.

Their solution to problems is not to recognize the

necessity of free public mass transit with

enlightened planning to favour working people,

including the use of software applications for

example to connect passengers with public

micro-buses. It is to find ways to increase car

use, disrupt the traditional taxi industry,

exploit the large numbers of vulnerable workers

desperate for work, especially new immigrants, and

in this way abscond with ever greater amounts of

the economy's social wealth.

To launch

their expansions into new cities, the

supranational ride hailing companies attempt to

gain favourable public opinion from users of their

apps through repeated exposures in the mass media

of the chaos, anarchy and shortcomings of urban

mass transit and in particular the taxi industry.

Their solution to problems is not to recognize the

necessity of free public mass transit with

enlightened planning to favour working people,

including the use of software applications for

example to connect passengers with public

micro-buses. It is to find ways to increase car

use, disrupt the traditional taxi industry,

exploit the large numbers of vulnerable workers

desperate for work, especially new immigrants, and

in this way abscond with ever greater amounts of

the economy's social wealth.

The oligarchs spend millions of dollars to advertise and lobby political representatives at various levels to open the door for their operations to skirt existing regulations especially those governing the taxi industry and to operate with impunity on the backs of the working class. With a wink and a nod they float the fiction that ride hailing drivers are not their employees but so-called independent contractors and not worthy of even minimal labour standards. This illusion eliminates in a flash any notion of regular stable employment, overtime pay, paid vacations and holidays, or payroll deductions for employment insurance, injured workers' compensation and pensions.

The software platform companies already have a substantial section of the working class in a vulnerable contracted form of employment. Even before Uber began operations in the BC Lower Mainland in late January, it had 90,000 workers-on-demand as drivers in Canada. Beyond drivers delivering passengers and food, hotel workers and others are being trafficked through apps and assigned to specific workplaces for a limited time called a gig. By 2016, Statistics Canada estimates the number of gig or workers-on-demand had swollen to 1.66 million workers.

To avoid corporate income taxes, payment through the software app goes out of the country, at least with Uber according to several investigations, usually to the Netherlands and then on to tax havens like Bermuda. Much of the money as profit is reportedly used to conquer new areas such as Uber and Lyft have done in BC with the NDP/Green coalition government giving them the right to operate without any of the regulations now governing the taxi industry, and without concern for the added pollution and vehicle congestion on the roads and the obvious abuse of vulnerable workers and reduced income for taxi drivers.

TML Weekly calls on Canadians to provide full support to the campaigns currently underway to organize ride hailing drivers and delivery workers in defence of their rights and claims on the new value they produce, as well as to denounce the cartel parties in power for capitulating to the pressure from the supranational financial oligarchy to facilitate pay-the-rich schemes.

See Uber

Drivers United and Justice

for Foodora Couriers! for further

information.

Highlights of Statistics Canada Report Measuring Workers in the Gig Economy

The following is pertinent information concerning gig workers gleaned from a December 2019 Statistics Canada research paper, "Measuring the Workers-On-Demand Gig Economy in Canada," which studied tax and administrative data from the Canada Revenue Agency(CRA), Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD), Labour Force Surveys (LFS) and other sources. Separate comments from TML Weekly are indicated with square parenthesis.

Gig workers are usually not employed on a

long-term basis by a single firm; instead, they

enter into various contracts with firms or

individuals (task requesters) to complete a

specific task or to work for a specific period of

time for which they are paid a negotiated sum.

This includes independent contractors or

freelancers with particular qualifications and,

increasingly, on-demand workers hired for jobs

that are offered and mediated through the growing

number of online platforms and crowdsourcing

marketplaces such as Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit,

Upwork, Guru, Fiverr and Freelancer. Gig workers'

earnings and work activity are uncertain, minor or

occasional.

From 2005 to

2016, the percentage of gig workers to total

workforce in Canada rose from 5.5 per cent to 8.2

per cent. This represents 1,666,061

worker-on-demand gig workers in 2016. These

workers-on-demand either earned no reportable

wages or salaries as T4 taxable income or combined

their gig work with T4 taxable wages or salaries.

Some of the increase to 8.2 per cent coincided with the introduction and proliferation of online platforms employing on-demand workers with very "flexible" and often minimally binding work arrangements (Uber, Lyft etc).

The annual income of a typical gig worker was usually low. The median net gig income in 2016 was only $4,303. Lower paid workers in the bottom 40 per cent of the annual income distribution were about twice as likely to be involved in gig work as other workers.

Gig work was generally only a temporary activity. Roughly one-half of those who entered gig work in a given year had no gig income the next year. However, a non-negligible share of gig work entrants -- about one-quarter -- remained gig workers for three or more years.

Gig work was more prevalent among immigrants than among Canadian-born people. In fact, 10.8 per cent of male immigrant workers who had been in Canada for less than five years were gig workers in 2016, compared with 6.1 per cent of male Canadian-born workers.

A 2017 survey found that nine per cent of the Greater Toronto Area workforce worked through online platforms. People who work through online platforms are only part of the gig economy since not all gig workers do.

Gig workers

are likely to be classified at this time for tax

purposes (and whether they qualify or not for

state-organized and company paid or co-paid

benefits such as Employment Insurance (EI),

Workers' Compensation and the Canada Pension Plan)

as unincorporated self-employed workers who report

business, professional or commission income on

their income tax returns. They must fill out a

T2125 Statement of Business and Professional

Activities and file it with their T1 tax form.

They do not receive a T4 record of earnings from

their workers-on-demand employer.

Statscan defines workers as all individuals who: (a) reported any employment income from T4 slips or other employment income such as tips, gratuities or director's fees on their T1 forms, (b) reported any unincorporated self-employment income on a T2125 Statement, or (c) were identified as owners of incorporated businesses through corporate tax returns and worked in their business.

The Labour Force Survey puts workers into categories: private and public employees, incorporated self-employed workers with and without employees, unincorporated self-employed workers with and without employees, and private employees working in family businesses without pay.

Statscan says gig workers are not wage employees, do not have a long-term contract with any employer, do not have a predictable work schedule and do not have predictable earnings. They are classified as unincorporated self-employed freelancers, day labourers, or on-demand or platform workers. Statscan identifies gig workers in part by how workers report their work arrangements to tax authorities.

[Comment: In this way, the employer and state authorities subjectively classify workers as workers or not according to whatever favours the interests of those who buy the exchange-value of the capacity to work of the working class and take control of its use-value and the social product workers produce. According to a particular labour law or code, a classification as unincorporated or even incorporated self-employed freelancers, day labourers, or workers-on-demand employed through a software platform or on contract through worker traffickers may mean the employer does not have to guarantee standards for overtime pay, paid vacations, minimum wage, paid sick leave; ensure and pay or co-pay for any state-organized benefits and payroll deductions for EI, injured workers' compensation or pensions; meet certain established standards for insurance for a particular job, qualifications for the work, safety while working, or recognize the legal right to form a collective defence organization (union).

This means these software platform companies can drive down the standard of living of the working class using new forms of class struggle against workers. They also act as disruptors of traditional businesses, in particular the taxi industry at this time. The ride hailing companies and others using software platforms are not subject to the market prices that public authorities have in place for taxi companies, the established exchange-value for the capacity to work of those employed, other standards for insurance and licensing, the number of cars they can deploy and the demand that a certain number of cars must be equipped to handle passengers with special needs.

This means that Uber and Lyft, for example, can undercut the market prices and steal market share from the already established taxi companies and drive them out of business. The software platform companies operating outside the established norms can disrupt the traditional companies, drive them out of business, drive down workers' wages and terms of employment, and then gradually increase the market prices they charge to achieve maximum private profits. Also, Uber and Lyft are not restricted from charging "surge" prices during periods of heavy demand or whenever they set their algorithms to do so. After only one week of Uber and Lyft operating in Vancouver, both taxi companies and drivers reported a decline of 30 per cent in their operations. The proliferation of ride hailing and car share software platforms also acts to worsen the overall anarchy and chaos of the urban transportation system, generating yet more congested roads, traffic jams, accidents and air pollution.

Without companies issuing a T4 tax slip for what workers receive in return for the exchange-value of their capacity to work, the added-value the workers-on-demand company expropriates from the sale of the service that workers produce can be hidden from any public authority. In this case the employer does not have to declare any difference between the gross income from selling the service (or good) the worker produces for which a customer pays, and the amount the employer deducts from the gross income to pay the exchange-value of the worker's capacity to work and for any consumed transferred-value from fixed equipment and circulating material or fees. The employer can hide and move the expropriated added-value (profit) out of the economy and country to a tax-free haven. According to numerous reports, the practice of Uber is to send the entire gross income to the Netherlands, from where it returns the exchange-value for the driver and any money needed to pay for already-produced transferred-value and fees. The remaining added-value (profit) is apparently then sent to the tax-free haven of Bermuda.]

***

The median business income of unincorporated self-employed workers was $10,000 in 2013. Less than four per cent of unincorporated self-employed workers in the CEEDD had employees. This result was consistent with the notion (using tax data) that self-employment work is a relatively minor activity for many individuals identified as unincorporated self-employed workers.

Among gig workers, 48.6 per cent had no wage-earning job and reported no employment income (on a T4); while 36.3 per cent had one wage job and about 15.1 per cent had multiple wage jobs. This indicates gig workers were split almost evenly between those who had no other earnings except for their gig earnings and those who supplemented their wages and salaries with the earnings from their gig activities. The median net income for gig workers was $4,303 in 2016.

The median share of gig income compared with total earnings was 76 per cent, meaning that for about half of all gig workers, gig earnings represented more than three-quarters of their total annual earnings. For more than one-quarter of all gig workers, their gig earnings represented all of their earnings.

A sharp

increase in the number of gig workers corresponds

with the 2008/2009 recession, and it was somewhat

sharper for men than for women. The timing of the

increase suggests that the growth in the share of

gig workers during those years can be largely

attributed to push factors such as declining

employment prospects. A second sharp increase was

observed around 2012/2013, but the reason why is

less intuitive and may be related to the

proliferation of online platforms in Canada that

started around that time.

The share of gig workers was substantially higher among women than among men -- and this gap has widened over time. In 2016, the share of female gig workers to all female workers was about 9.1 per cent, while the share of male gig workers was about 7.2 per cent. These percentages translate into about 991,320 total gig workers in 2005 and 1,666,061 gig workers in 2016.

In terms of the duration of gig work, 56.4 per cent of gig workers who entered in 2013 (i.e., those who were gig workers in 2013 but not in 2012) remained gig workers for at least one year, while 39.1 per cent remained gig workers for two consecutive years and 29.8 per cent remained gig workers for three consecutive years. Uber started its operations in Canada in 2012 and recently began operating in Vancouver. In 2019 it reported 90,000 drivers in Canada alone and 3.9 million worldwide. The biggest rideshare online platform company in China, called Didi Chuxing, has 21 million drivers.

Gig workers with no (additional) wage or salary earnings spiked around the recession in 2008/2009, but remained relatively stable until another spike in 2012/2013.

Gig workers with (additional) wage or salary earnings increased virtually linearly from 2006 to 2016, with only minor bumps around 2008/2009. The linear trend was particularly apparent among female gig workers with additional wage or salary earnings.

Gig work became more prevalent from 2005 to 2016. Gig workers with no wage earnings seem to have responded more strongly to both push factors (recession) and pull factors (proliferation of online platforms). Overall, however, an increasing share of workers do gig work in addition to their main wage-earning jobs, but also an increasing share of gig workers do not earn any additional wages or salaries.

Entry into gig work in the United States is generally preceded by a decline in non-gig income. A similar pattern was found in Canada. T4 earnings dropped dramatically in the year an individual entered gig work, and this drop in T4 earnings was larger for men than for women.

EI benefits rose before the entry into gig work and dropped sharply in the first year of gig work. For women, this pattern was observed for both regular and special EI benefits (maternity).

Researchers asked whether the decline in wages and salaries before the first year of gig work was the consequence of outside shocks such as job loss or wage cuts. Given the EI eligibility rules, the rise in EI benefits before entry into gig work seems to suggest that outside shocks are important contributors to the decision to enter gig work.

Unincorporated self-employed workers who report professional, business or commission income (e.g., Uber and Lyft drivers and delivery workers) attach a T2125 Statement of Business and Professional Activities to their T1 (tax) forms. The T2125 form details all revenues and expenses related to the individual's unincorporated business and professional activities.

The rate of unincorporated self-employment from 2005 to 2016 overall was stable, yet with a rising share of gig workers among all Canadian workers. This implies that increasing numbers of unincorporated self-employed workers are gig workers who file at least one T2125 form.

Did gig work

replace or supplement less precarious forms of

unincorporated self-employment that are associated

with a formal business? First, unincorporated

self-employed workers continued to file T2125

forms at the same rate, but were increasingly less

likely to report a Business Number. A Business

Number is associated with an actual business. In

this scenario, gig work replaced more stable forms

of self-employment that required stronger

commitment and possibly larger initial investment.

More gig activities are now possibly reported to the CRA because more gig work is done through online platforms, unlike in the past, where much of it was done through informal referrals from friends, neighbours, (underground) etc.

[Comment: Online platform employers refuse to issue T4 slips as part of the fraud that the workers providing the service through the platform are self-employed and not workers selling their capacity to work. This means the online business does not have to meet any federal or provincial standards regarding terms of employment such as overtime, paid statutory holidays and vacations, and contribute to EI and Workers' Compensation payroll taxes etc.]

The increase in the share of gig workers represents both a decline in the share of unincorporated self-employed workers with a steady business and an increase in the number of self-employed workers who do gig work in addition to their main business activity.

No age group dominated the age distribution of gig workers; gig workers were spread more or less evenly across the entire age spectrum.

The shares of gig workers among all workers were higher where opportunities for gig work were greater, specifically in the three regions that have major Canadian urban centres -- Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver.

Forty-nine point eight per cent of male gig workers and 45.2 per cent of female gig workers belonged to the lowest two quintiles of the total income distribution. Among both men and women, the prevalence of gig workers in the top income quintile was roughly half the prevalence of gig workers in the bottom income quintile. (See charts in full report for quintiles.)

Most male gig workers worked in professional, scientific and technical services (19.0 per cent); construction (12.4 per cent); and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services (10.6 per cent), which includes activities such as administration, hiring and placing personnel, preparing documents, providing cleaning services, and arranging travel.

Female gig workers are concentrated primarily in health care and social assistance (20.2 per cent) and professional, scientific and technical services (17.4 per cent).

The industrial distribution of gig workers was based on the industry of their main job. The industry with the highest share of male gig workers was arts, entertainment and recreation (15.6 per cent), which is the industry that originated the term "gig work." A high prevalence of gig workers was also observed in health care and social assistance (13.3 per cent), educational services (11.3 per cent) and real estate and rental and leasing (10.8 per cent).

Among women, the industry with the highest share of gig workers was other services (20.1 per cent), a broad category that includes personal care providers, cooks, maids, caretakers and nannies (but excludes public administration).

A recent study found that much of the recent increase in independent contracting in the United States was driven by rapid growth in the transportation sector that can be directly linked to Uber and similar online platforms. There was a sharp increase in the share of gig workers in taxi and limousine services in the mid-2010s. Yet even in 2016, when the share of male gig workers in taxi and limousine services almost doubled compared with 2014, this share did not exceed three per cent of all male gig workers.

Over one-third of all male gig workers (36.0 per cent) had a university degree, while a similar percentage of male gig workers had only a high school diploma or less.

There was a particularly high prevalence of gig workers among men (13.7 per cent) and women (16.5 per cent) who held graduate degrees (master's degree and higher). It is likely that the proliferation of supply-driven crowdsourcing marketplaces such as Upwork and Freelancer has driven this number.

More than one-third of all male gig workers and more than one-quarter of all female gig workers had only a high school diploma or less, and just over one-third of both male and female gig workers had a university degree. Statscan notes that workers in the upper quintiles of the income distribution were less likely to be gig workers than those in the lower income quintiles.

The shares of gig workers were considerably higher among immigrants, especially recent immigrants, than among Canadian-born workers. More than one-third of all male gig workers were immigrants -- a far larger share than the share of immigrants in the Canadian labour force (about 24 per cent in 2016). Even immigrants who had been in Canada for 20 years or more were more likely to be identified as gig workers than Canadian-born workers. Among recent immigrants, immigrant men were more likely to be gig workers than immigrant women but the opposite was true for immigrants who had been in Canada for 20 years or more.

Nineteen point six per cent of male gig workers were individuals with main occupations as trades, transport and equipment operators, and related occupations. Female gig workers were concentrated in sales and service occupations (22.1 per cent) and occupations in education, law, and social, community and government services (20.3 per cent).

The shares of gig workers among all workers were the highest among workers with main occupations in art, culture, recreation and sport (24.2 per cent for men and 26.6 per cent for women). About 8.6 per cent of male gig workers and 9.8 per cent of female gig workers reported not working in either 2015 or 2016 in the census.

For lengthy excerpts from the research paper click here.

For the complete research paper, click

here.

For Your Information

Workers' Capacity to Work and the Contradiction between Its Exchange-Value and Use-Value

The Statscan definition of a worker is broader than that of federal and provincial labour laws, which introduce issues such as control of the conditions of work and whether those who sell their capacity to work have any input into the terms of employment or own any of the equipment used in the work. All these definitions are in contradiction with the concrete conditions of the imperialist economy and its mode of production and state structure dominated by a financial oligarchy that exploits the working class.

The

imperialist economy consists of two main social

classes, the working class and financial

oligarchy. The working class, to acquire a living

through work, sells its capacity to work, and goes

to work for those who buy it. Those who buy the

capacity to work of the working class, led by the

financial oligarchy, control the main means of

production, the state structure and its

enterprises, and the social product workers

produce, including the added-value, which forms

the basis for profit.

The

imperialist economy consists of two main social

classes, the working class and financial

oligarchy. The working class, to acquire a living

through work, sells its capacity to work, and goes

to work for those who buy it. Those who buy the

capacity to work of the working class, led by the

financial oligarchy, control the main means of

production, the state structure and its

enterprises, and the social product workers

produce, including the added-value, which forms

the basis for profit.

Generally no activity within the imperialist economy is considered legitimate or desirable unless it falls under the control of the financial oligarchy and serves to expand or preserve its private social wealth through the expropriation of a portion of the new value workers produce, the added-value. In sum, no economic activity under imperialism holds any utility for the financial oligarchy in control unless it can increase or preserve its social wealth and power.

Capacity to Work

Similar to all commodities on the market, the capacity to work of the working class has an exchange-value and use-value. Unlike other commodities, the use-value of the capacity to work is always greater than its exchange-value. The exchange-value is equivalent to the value that has gone into forming the capacity to work of workers since birth and adjusted according to its supply and demand on the labour market and the level of class struggle the working class has organized to defend its claims and rights.

The use-value is equivalent to the new value the capacity to work produces within the imperialist economy. The new value workers produce consists of an equivalent of its exchange-value, called reproduced-value, plus an additional value, called added-value, which forms the profit those who buy the capacity to work expropriate.

Workers in the imperialist labour market sell their exchange-value. Those who buy the capacity to work put workers' use-value to work and seize the social product the use-value produces. The social product contains the transferred-value from already-produced value consumed during the production process and new value, which consists of a reproduced amount equivalent to the exchange-value of the capacity to work and an additional amount, the added-value, that those who buy the capacity to work expropriate as profit.

Workers who sell a service or good they produce themselves outside the imperialist labour market have negligible presence in the economy. In this instance, they do not sell their capacity to work as exchange-value to a buyer who takes control of it. They may sell their capacity to work on the labour market regularly or not, and produce their own goods and service as supplementary income, which they may or may not report to the CRA. This depends in large measure on whether the buyer of the good or service demands a receipt for income tax purposes.

Workers Outside the Imperialist Labour Market

Workers engaged in directly selling their own goods and services receive payment for the value of the commodity they produce, which includes the use-value of their capacity to work for the particular period of work and any already-produced (old) value they may use. If fully realized, the total received is equivalent to the price of production of the good or service the worker produced and sold. In this way, workers do not sell their capacity to work as exchange-value to someone else. They retain control of the use-value of their capacity to work and directly sell whatever they produce. Their capacity to work is not alienated to another who buys its exchange-value and in doing so gains control of the use-value and the full value of production, which is greater than the amount paid for the exchange-value.

Statscan writes, "The methodological approach taken in this study is not without limitations. Admittedly, this approach is unlikely to capture activities such as occasional babysitting, dog walking, lawn care, (house sitting, housecleaning and home renovations), or similar informal activities usually settled between family members, friends and neighbours. These activities have always been part of daily life, but are not usually considered labour market activities, and are therefore a lesser priority for researchers interested in labour market dynamics. According to a recent Canadian study based on data from the Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations, about 30 per cent of respondents reported that they participated in some form of paid informal activity. However, when those who participated in such activities for fun were excluded, the share dropped to 18 per cent."

Work done outside the imperialist labour market and a social relation with those who buy workers' capacity to work may be the only work a worker engages in, or as a means to earn extra money in conjunction with selling their capacity to work on the labour market part-time or full-time or while studying. This often basic work outside the imperialist labour market and the exploitive social relation predicts in a crude form a new direction for the economy where a modern working class controls its capacity to work without having to sell and alienate it on a labour market. This requires the working class organizing itself as a powerful independent economic and political force to free itself from the exploitive social relation with the financial oligarchs, negate their control of the main means of production and state structure, and build new forms and institutions leading to the complete emancipation of the working class and elimination of all forms of exploitation of humans by humans.

Social Relation Between Those Who Sell Their

Capacity to Work

and Those Who Buy It

Workers within the imperialist economy and its labour market exist in a social relation with those who buy their capacity to work. The buyer or employer pays workers for the exchange-value of their capacity to work. Once purchased, the capacity to work is alienated from the seller. The buyer takes control of the seller's capacity to work, transforms it into a use-value and puts it to work.

The realization of the exchange-value of the capacity to work through a wage or other form of payment transforms the exchange-value into a use-value under the control of the buyer. The use-value of the capacity to work for a given period is equivalent to the new value workers produce, which is greater than the exchange-value paid for the same period. The use-value at work reproduces its exchange-value and produces an additional amount called added-value, which forms the basis of profit. The sum of the reproduced-value and added-value is the new value equal to the use-value of the capacity to work for a given period.

Workers in the imperialist economy produce added-value that their employer expropriates as profit. Workers who sell their capacity to work and those who buy it form a dialectical social relation. The social relation is the fundamental condition or social relation under imperialism for workers to acquire a living and for the financial oligarchy to expropriate profit.

The buyer of the exchange-value of the capacity to work dominates the social relation because buyers dominate the imperialist mode of production; they own or control the means of production and the social product workers produce and the state structure.

Sellers of their capacity to work, the working class, must organize collectively to defend themselves and their claims and rights within the concrete conditions of the exploitive social relation. To extricate themselves from this despotic situation requires the working class freeing itself from the social relation with the buyers of the exchange-value of its capacity to work. Resolving the dialectic demands an organized class struggle to break out of the social relation and bring into being a modern working class, a synthesis that gains control of its capacity to work within a new mode of production and state structure and is no longer captured within a social relation with those who buy its capacity to work. With this synthesis and new direction for the economy, modern workers will own and control the means of production and entire social product they produce and state structure, and be in a position to plan and utilize their capacity to work and the social product they produce to guarantee the rights of all and society, and humanize the social and natural environment.

Uber and Lyft Buy the Exchange-Value of the

Capacity to Work of Their Drivers

Workers who drive for Uber or Lyft sell the exchange-value of their capacity to work to the companies that own and control the ride hailing software platforms and the realized (paid) rides and other services the drivers produce. Uber and Lyft use the capacity to work, which they have purchased as exchange-value, and employ it as use-value to produce social product, mostly rides from point A to point B but also for other services such as delivery, cleaning, hotel and warehouse work and public services.

The passenger/buyer of the service, the ride, pays with a credit card for the use-value the driver produces and for the transferred-value of already-produced value such as a car and gas, and other prorated associated charges per length and duration of the ride for insurance, licensing and other fees. The company realizes the payment of the exchange-value of the driver using a portion of the amount the passenger pays for the ride; the company pays an agreed upon portion for transferred-value and fees, and expropriates the remaining new value the driver has produced as profit (the added-value).

The ride hailing companies and others using software platforms are not subject to the market prices that public authorities may have in place for taxi companies or the number of cars they can deploy or the established exchange-value for the capacity to work of those employed. Uber and Lyft can undercut the market prices and steal market share from the already established taxi companies and drive them out of business as they are already doing in Los Angeles and New York. The software platform companies use the new productive forces to favour the financial oligarchy and not to favour the working class and economy. Their increasing predatory attacks on the working class, such as worker trafficking and precarious work, drive down workers' wages and terms of employment.

Within the social relation between workers who sell their capacity to work and those who buy it, the method used to determine the particular amount of the exchange-value in money can vary considerably. Payment of the exchange-value of the capacity to work can be for a specific time -- such as one hour, a day or longer -- called a wage or salary; or for a certain volume of goods or services called piecework; or payment for a particular task or service, which resembles the practice of hiring workers-on-demand or gig work that may combine both time and volume (i.e. the time and distance of a ride). The payment of the exchange-value of the capacity to work comprises only a portion of the new value workers produce from the use-value of their capacity to work in action. Those who buy the exchange-value of the capacity to work expropriate the other portion of the new value as profit (the added-value).

Whether workers own their own tools, clothes or even certain equipment used in the work, such as a car, does not alter the exploitive social relation they enter into with those who buy their capacity to work. Workers' ownership or not of certain fixed and circulating material consumed in the course of work does not change the social relationship between workers who sell the exchange-value of their capacity to work and those who buy it. In fact, forcing workers to buy certain fixed and circulating already-produced value used in work, which Uber and Lyft do with regard to vehicles, increases the rate of profit for those who buy workers' capacity to work.

Workers do

not have the individual social wealth to buy and

own larger more expensive means of production,

such as factories and machinery, although this

could be done collectively as a front of class

struggle to augment the independent economic

strength of the working class in preparation for

freeing itself generally from the despotic social

relation with the financial oligarchy.

Issues of control and terms of employment while working, including the amount received as exchange-value and certain aspects of how the job is performed, form part of the dialectical social relation workers enter into with those who buy their capacity to work. These are determined in part through class struggle and can result in workers having very little or substantial control over working conditions, according to the effectiveness and strength of their organized defence of their rights. For example, safety committees workers organize and enforce through their terms of employment can play a substantial role in controlling how work is performed. The degree of control workers may exercise through organized class struggle does not change the fundamental exploitive social relation with those who buy their capacity to work. By breaking out of the despotic social relation and organizing a new direction for the economy, the working class can free itself from the imperialist economy and financial oligarchy and chart a new pro-social path forward for humanity.

(To access articles individually click on the black headline.)

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca

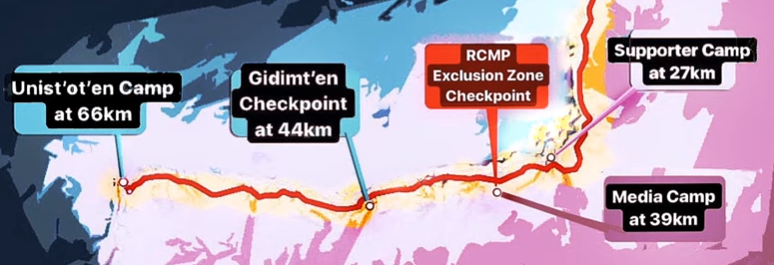

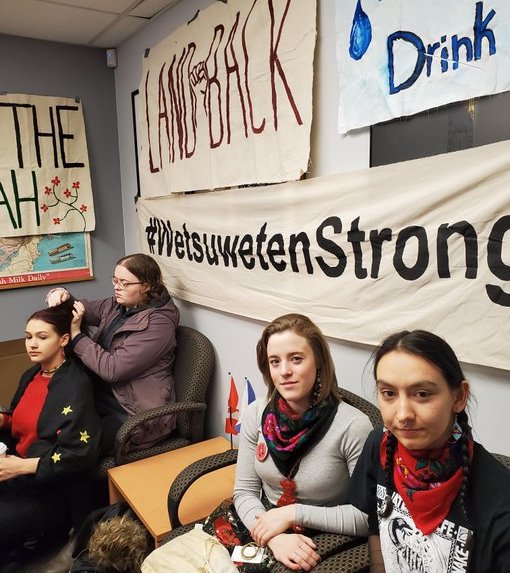

Grand Chief Stewart

Phillip, President of the Union of BC Indian

Chiefs (UBCIC) stated, "We are in absolute outrage

and a state of painful anguish as we witness the

Wet'suwet'en people having their Title and Rights

brutally trampled on and their right to

self-determination denied. Forcing Indigenous

peoples off their own territory is in complete and

disgusting violation of the United Nations

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,

which the Horgan government recently committed to

uphold through Bill 41, and which the Trudeau

government has also committed to uphold through

yet to be introduced legislation. Indigenous

rights are human rights and they cannot be ignored

or sidestepped for any reason in the world, and

certainly not for an economic interest. We call on

the RCMP to immediately stand down, and we call on

the Crown to immediately take responsibility for

ending this violence."

Grand Chief Stewart

Phillip, President of the Union of BC Indian

Chiefs (UBCIC) stated, "We are in absolute outrage

and a state of painful anguish as we witness the

Wet'suwet'en people having their Title and Rights

brutally trampled on and their right to

self-determination denied. Forcing Indigenous

peoples off their own territory is in complete and

disgusting violation of the United Nations

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,

which the Horgan government recently committed to

uphold through Bill 41, and which the Trudeau

government has also committed to uphold through

yet to be introduced legislation. Indigenous

rights are human rights and they cannot be ignored

or sidestepped for any reason in the world, and

certainly not for an economic interest. We call on

the RCMP to immediately stand down, and we call on

the Crown to immediately take responsibility for

ending this violence."