|

Supplement

No. 21June 8, 2019

75th Anniversary

of D-Day

Attempts to Sow

Divisions Dishonour

All Those Who Fought Together to

Defeat Fascism

- Nick Lin -

Allied casualties are helped ashore on the beaches of Normandy, France

on D-Day.

• Behold

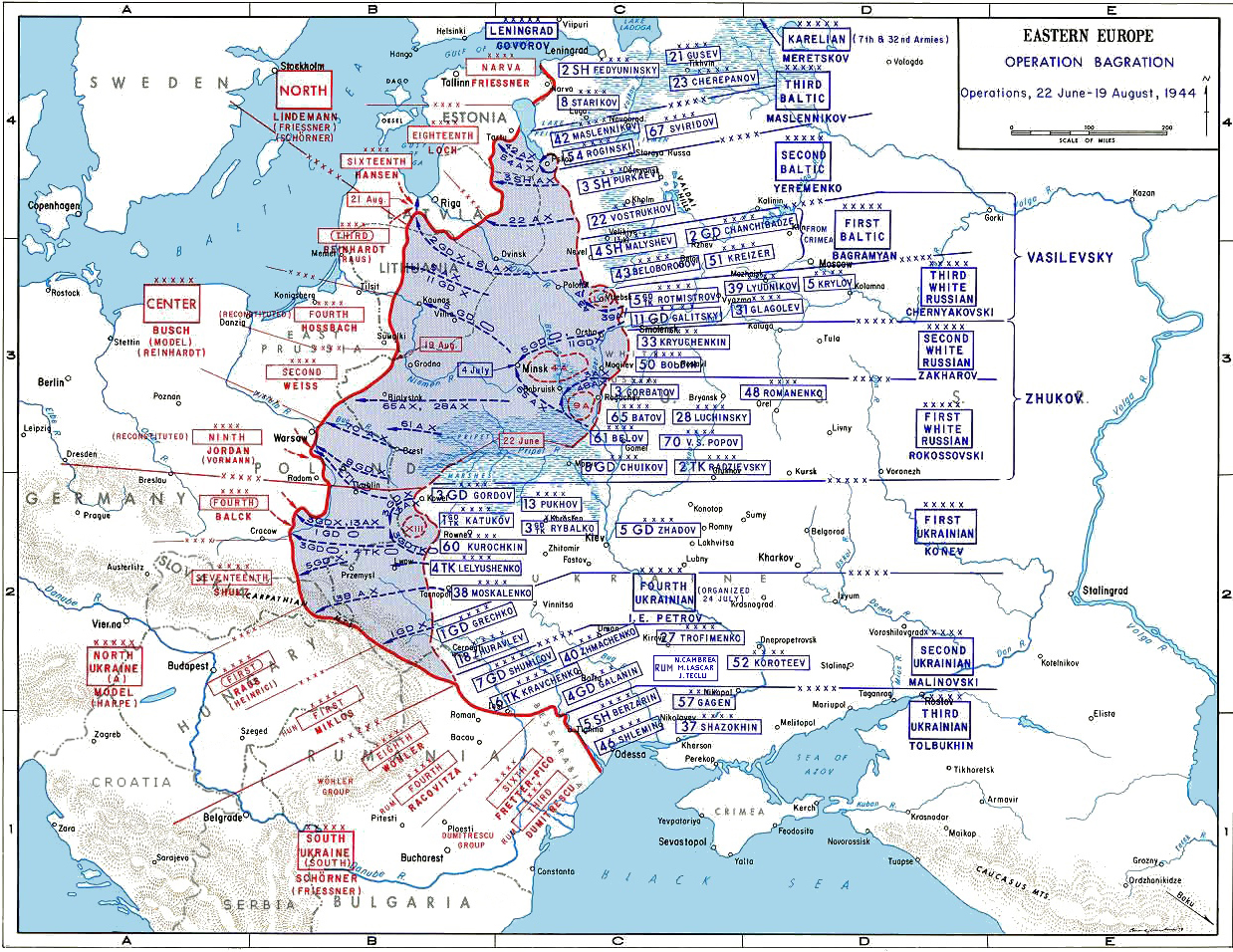

Operation Bagration, D-Day of

the Eastern Front

- John Wight -

• The Road

to

Berlin

- Stan Winer -

75th Anniversary of D-Day

- Nick Lin -

June 6 marked the 75th anniversary of D-Day, June 6,

1944, when

Britain and the U.S. opened a second front against Nazi Germany with a

massive amphibious assault on the beaches of Normandy in occupied

France. The Soviet Union, fighting with incredible resilience and

sacrifice to the east, had long-awaited this development promised

by its allies. It made its own contribution to D-Day with the

coordinated Operation Bagration on the eastern front.

This year, the representatives of Britain, the U.S.,

France, Canada and others attending the main ceremonies in France, were

more boorish than ever in assigning the victory over fascism to

themselves and making no mention of the Soviet Union whatsoever. Their

refusal to acknowledge all those who contributed to the defeat of

fascism in World War II, conspicuously ignoring the role of the Soviet

Union and the Red Army, brings them no honour. Nay more, it causes

great offence to all those who sacrificed so much to defeat fascism in

their own countries as well.

For his part, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who attended the

ceremonies in Europe, issued a D-Day statement that referred to the

Allied forces, but totally omitted any mention of the Soviet Union, a

key member of the Allies. The statement concluded, without irony, with

the line "Lest we forget."

These attempts to sow divisions today dishonour all

those who

fought against fascism, a victory that was only possible because of the

tremendous sacrifice of the Soviet peoples acting together with the

U.S., Britain and others, a victory that was hastened by D-Day. Such

disinformation is not only self-serving but constitutes malicious

activity

by the Anglo-American imperialists, intended to portray their

present-day imperialist war and aggression as akin to the anti-fascist

struggle, and the essential factor for world peace and stability.

At the same time, the peoples of the former Soviet

countries

proudly celebrate their unparalleled contributions to the defeat of

fascism on Victory Day, May 9, in a magnanimous spirit in which

everyone's contributions are acknowledged and everyone is invited to

take part in the worldwide marches of the Immortal Regiment. This is

portrayed by bourgeois media, especially in the U.S., as "pro-Russian"

and "militaristic," and therefore unacceptable.

The Soviet Union bore the brunt of the Nazi aggression

during World

War II. Who if not the Red Army veterans and their descendants have a

right to have these sacrifices acknowledged and commemorated?

As TML Weekly

pointed out on the occasion of V-E Day, "Today it is commonplace to

hear the Anglo-American and European imperialists dismiss the feats of

the Soviet peoples in defeating Hitler, while claiming that it was the

historic landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944, which broke Hitler's

back. This makes it possible to claim that the United States played the

decisive role in saving the world from Hitlerism and describing current

U.S. wars of aggression and occupation as wars of liberation. All U.S.

military interventions since the landing at Normandy are said to oppose

dictatorships and tyrannies similar to Hitler's, thus faithfully

following in the tradition of the landing at Normandy."

In light of the unacceptable disrespect to the Soviet

Union, Russia

and Red Army veterans that unfolded at the commemoration of the 75th

anniversary of D-Day, remarks by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov

in a June 5 article in Foreign Affairs Magazine, are all the

more pointed. He noted:

"Bitter as it is to witness, we see the attempts to

discredit the

heroes, to artificially generate doubts about the correctness of the

path our ancestors followed. Both abroad and in our country we hear

that public consciousness in Russia is being militarized, and Victory

Day parades and processions are nothing other than imposing bellicose

and

militaristic sentiment at the state level. By doing so, Russia is

allegedly rejecting humanism and the values of the 'civilized' world.

Whereas European nations, they claim, have chosen to forget about the

'past grievances,' come to terms with each other and are 'tolerantly'

building 'forward-looking relations.'

"Our detractors seek to diminish the role of the Soviet

Union in

World War II and portray it, if not as the main culprit of the war,

then

at least as an aggressor, along with Nazi Germany, and spread the

theses about 'equal responsibility.' They cynically equate Nazi

occupation, which claimed tens of millions of lives, and the crimes

committed

by collaborationists, with the Red Army's liberating mission. Monuments

are erected in honour of Nazi henchmen. At the same time, monuments to

liberator soldiers and the graves of fallen soldiers are desecrated and

destroyed in some countries. As you may recall, the Nuremberg Tribunal,

whose rulings became an integral part of international

law, clearly identified who was on the side of good and who was on the

side of evil. In the first case, it was the Soviet Union, which

sacrificed millions of lives of its sons and daughters to the altar of

Victory, as well as other Allied nations. In the second case, it was

the Third Reich, the Axis countries and their minions, including in the

occupied

territories.

[...]

"We hold sacred the contribution of all the Allies to

the common

Victory in that war, and we believe any attempts to drive a wedge

between us are disgraceful. But no matter how hard the falsifiers of

history try, the fire of truth cannot be put out. It was the peoples of

the Soviet Union who broke the backbone of the Third Reich. That is a

fact."

Posted below are articles presenting a

recounting of

the Red Army's Operation Bagration, notable events at this year's

commemoration of D-Day, as well as an item that details the

prevarications and ulterior motives that characterized the U.S. and

British participation throughout World War II, including D-Day.

- John Wight -

Map of Operation Bagration, showing the massive westward thrust of the

Red Army.

Operation Bagration was the D-Day of the Eastern Front.

In scope,

size, scale and impact, it was a remarkable feat of arms unmatched in

WWII.[1]

Crucially, Overlord (D-Day) and Bagration were planned

and

undertaken as part of a coordinated effort on the part of the Grand

Alliance to break the back of German resistance in Europe with a

determination that was equally held by the Soviets, British and

Americans to force the unconditional surrender of Hitler's Germany.

In his book Stalin's

Wars, Geoffrey Roberts reveals

that "Soviet

plans for Operation Bagration were closely co-ordinated with

Anglo-American preparations for the launch of the long-awaited Second

Front in France. The Soviets were informed of the approximate date of

D-Day in early April and, on 18 April, Stalin cabled Roosevelt and

Churchill that, 'as agreed in Tehran, the Red Army will launch a new

offensive at the same time so as to give maximum support to the

Anglo-American operation.'"

Though both operations were of immense military and

strategic

importance, Bagration dwarfed Overlord. It began on June 22, the third

anniversary of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, with air

attacks on enemy artillery positions and concentrations, guided by

partisan units operating behind German lines.

The main offensive began on June 23 along a 500-mile

front, involving close to two million troops.

Operation Bagration was designed to complement D-Day,

to effect the

liberation of the Soviet territory from the Nazis and destroy the

Wehrmacht as a serious fighting force in the East. It achieved all

three of these objectives and more.

As British historian and author David Reynolds points

out: "In five

weeks the Red Army advanced 450 miles, driving through Minsk to the

outskirts of Warsaw and tearing the guts out of Hitler's Army Group

Centre. Nearly 20 German divisions were totally destroyed and another

50 severely mauled -- an even worse disaster than Stalingrad."

He goes on: "This stunning Soviet success occurred while Overlord was

still stuck in the hedges and lanes of Normandy."

The famed Soviet journalist and author, Vasily

Grossman, whose

collection of wartime journalism, A

Writer At War, is a classic work

that should be required reading for those interested in the reality of

war and conflict, describes with customary force and power the human

toll of the Soviet offensive:

"Sometimes you are so shaken by what you've seen," he

writes in one

report from the front, "blood rushes from your heart, and you know that

the terrible sight that your eyes have just taken in is going to haunt

you and lie heavily on your soul all your life." He continues:

"Corpses, hundreds and thousands of them, pave the road, lie in

ditches, under the pines, in the green barley. In some places, vehicles

have to drive over the corpses, so densely they lie upon the ground."

Despite the coordination of Operation Bagration with

D-Day, and

despite the former's ineffable military and strategic importance, not

one mention was made of it during the 75th D-Day anniversary

commemorations in Northern France. Such a glaring and unconscionable

omission stands as just one of many shameful examples of historical

amnesia on the part of Western governments and ideologues in recent

years -- people more concerned with politicizing history than they are

with respecting it.

Left: Tanks and other vehicles are abandoned by the Nazis as they flee

the Red Army during Operation Bagration in Belarus, July 1944. Right:

Some 57,000 German prisoners of war, captured during an encirclement

east of Minsk are paraded through Moscow, July 15, 1944.

The valour and courage of the 156,000 troops who landed

on the

Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944 is not in question, nor is that of the

thousands of sailors, airmen, and airborne troops who also took part in

D-Day. Operation Overlord was, and will likely remain, the largest

amphibious military assault ever mounted. In terms of its ambition,

planning and the coordination of the combined military forces of the

multiple nations involved, it deserves the place in military history

that it commands.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin more than understood the

importance and

achievement of D-Day, which he set out in a congratulatory telegram to

Roosevelt and Churchill at the time:

"As is evident, the landing, conceived on a grandiose

scale, has

succeeded completely. My colleagues and I cannot but admit that the

history of warfare knows no other like undertaking from the point of

view of its scale, its vast conception, and its masterly execution."

Wind things forward 75 years and the parlous quality of

statesmanship in the West, with the open violation of the spirit of the

Grand Alliance between East and West that is enshrined in Stalin's

telegram, has never been more lamentable. For example, French President

Emmanuel Macron served up a speech in commemoration of D-Day that

drew deep from the well of Western exceptionalism. In lauding NATO and

the European Union as positive achievements of the war, he confirmed

how deeply entrenched the malaise of historical amnesia runs in Western

European capitals.

The notion that the men who gave their lives on D-Day,

and

thereafter in Europe on the way to war's end in 1945, did so in order

to give birth to a continent dependent on Washington and in fear of

Moscow, is preposterous. The devastation that Russia suffered in the

war, moreover, the magnitude of losses the country incurred, demands

the

respect and reverence of everyone interested in drawing the right

lessons from this epic struggle of world-historical importance.

It is for this reason that the decision not to extend

an invitation

to Russian President Vladimir Putin to attend the 75th D-Day

anniversary celebrations is both a travesty and evidence of the gulf

that exists between those for whom history is a guide and those for

whom it is a weapon.

A Europe liberated from fascism but divided by a Cold

War that

shattered forever the hopes for a lasting and enduring peace of equals

-- for global stability and cooperation reflected in the war's Grand

Alliance between East and West -- is nothing to celebrate. It reminds

us

that, although so much was sacrificed and won by so many during the

war, so much was thrown away and lost by so few after it.

Operation Bagration and Operation Overlord should never

be spoken

of separately. Both were mounted at the same stage in the war by a

Grand Alliance that contained within it the seeds of a future that, if

it had come to pass, would've met the scale of the sacrifice needed to

emerge victorious.

The last word goes to Vasily Grossman: "Nearly everyone

believed

that good would triumph, that honest men, who hadn't hesitated to

sacrifice their lives, would be able to build a good and just life."

John Wight has written for a variety of newspapers

and websites,

including the Independent, Morning Star, Huffington Post, Counterpunch,

London Progressive Journal, and Foreign Policy Journal.

TML Note

1. Operation Bagration was named

after Pyotr Bagration (1765-1812), a Russian general of Georgian

origin. He was known for being innovative and creative in his tactics

to find the particular approach required by a given situation, as well

as for the great importance he gave to the training, education and

discipline of troops, and to ensuring their well-being.

- Stan Winer -

Excerpted from "If Truth Be Told:

Secrecy and

Subversion in an Age Turned Unheroic"

British commandos land at Gold Beach on D-Day.

With the invasion of Normandy on D-Day on June 6, 1944

the

terms of warfare in occupied France ceased to be ostensibly those

of Hitler and became clearly those of the Allied Expeditionary

Force. The cross-channel build-up provided it with at least twice

the number of men, four times the number of tanks, and six times

the number of aircraft available to the enemy.

On D-day itself the Germans had mustered only 319

aircraft

against 12,837 of the Western Allies whose military strength soon

increased to the point where they had effective superiority of 20

to one in tanks and 25 to one in aircraft. Yet, despite its vast

numerical superiority and other advantages in its favour, the

offensive of the Allied Expeditionary Force was characterised by

restraint. Compared with the Russians, who still bore the brunt

of fighting on the eastern front, the invading force was merely

playing about. It had 91 full-strength divisions facing Germany's

60 weak divisions whose overall strength was roughly equal to

only 26 complete divisions. The invasion force, consisting of

British, American and Canadian troops, thus engaged less than a

third of the total number of German divisions in France, while

the Red Army engaged 185 enemy divisions in the east. For every

German division engaged by the Western armies, the Red Army met

three. In terms of armoured units alone, of the roughly 5,000

tanks available to Germany, more than 4,000 were deployed on the

eastern front.[1] So

obvious was the disparity, most of the German divisions having

been deployed to fight Russia on the eastern front, that in real

terms a western front hardly even existed.

The invading force's lethargic ground offensive was

characterised by such obvious restraint as to cause bitter

resentment within some of the top-most British military echelons.

In the words of Major General John Kennedy, then Assistant Chief

of the General Staff: "For six weeks or so, (after the invasion)

the Germans did not attempt or even desire to move their

divisions in the Pas de Calais or elsewhere towards the scene of

action in Normandy."[2] The

West's failure to launch a concerted ground attack on the enemy

was similarly noted by the British Vice-Chief of General Staff,

General Sir David Fraser: "For a little while -- a few weeks of

August and September (1944) -- the Western Front was open, and a

determined effort on our part might have finished the war, with

incalculable strategic and political consequences, and with a

saving of the huge number of casualties suffered later ... it was

the last chance to seize this great strategic opportunity. It

failed, and the war went on."[3]

In Holland, General Montgomery's stated objective in

September

1944 was for British and American tanks and paratroopers to

capture bridges across various canals and rivers. But crucial

intelligence derived from Ultra intercepts and decrypts, and from

agents providing detailed reports of enemy movements and

reinforcements in the area, was either ignored or did not reach

Montgomery. On September 17 two American and one British airborne

divisions were dropped as an "airborne carpet" between Eindhoven

and Arnhem. A ground link-up was to have been affected with

Montgomery's 21st Army Group within two to three days. The agreed

plan was that once the lower Rhine was crossed, operations would

then be expanded against the Ruhr to bring an early end to the

war. Over 7,000 men, more than two thirds of the 1st Airborne

Division, were dropped in the Arnhem area, where British

intelligence had indicated only a maximum opposition of brigade

strength. The enemy's reaction was one of astonishment at their

good fortune. Arnhem and its environs had been chosen by the

Germans as a suitable place in which to refit two entire

divisions of the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, which were available

immediately to contest the landings. Their reaction was swift and

without mercy: At the key Arnhem bridge, 1,200 British

paratroopers -- the cream of the British Army -- were killed and

more than 3,000 taken prisoner.

An Overall Debacle in Holland

Allied paratroop drop in the Netherlands, part of Operation Market

Garden.

That was only the start of an overall debacle in

Holland,

resulting in a total Allied loss exceeding 17,000 killed, wounded

and missing in action.[4]

Scarce air transport resources had been diverted from useful

operations elsewhere to the disastrous paratroop drop at Arnhem.

The Commander in Chief of 2nd Tactical Air Force, Air Marshal

Arthur Coningham complained bitterly that "the freezing of air

transport during a week of fine weather, with ample ground

suitable for landings, when the American and British armies were

only halted through lack of fuel and ammunition supply, was the

decisive factor in preventing our armies reaching the Rhine

before the onset of winter."[5] A

further eight months would pass before Arnhem

was finally captured -- just a month before the war in Europe

ended. Montgomery, soon to be promoted to Field-Marshal and for

the sake of immediate press reaction, described the disaster at

Arnhem as "a 90 per cent success" -- drawing from Prince Bernhard

of the Netherlands the bitter retort: "My country can never again

afford the luxury of a Montgomery success."[6]

There were similar "successes" occurring elsewhere along

the

western front. In Belgium, where the stated intention of Supreme

Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) was to capture

the crucial maritime port of Antwerp, SHAEF disregarded explicit

intelligence warnings that the Germans were about to secure the

approaches to the port. The invading force, failing to move

swiftly on the offensive before the Germans completed defence

preparations, ended up with Antwerp rendered entirely useless to

them for the next six months. This made it impossible for an

immediate advance on the Ruhr or on Berlin, which would have been

practicable only if Montgomery's 40 divisions could be supplied

through Antwerp.[7]

Virtually the same kind of deliberate stalling,

procrastination

and prolongation of the war had occurred months earlier at Anzio

in Italy, where the Germans were wholly unprepared for amphibious

landings. Excellent conditions had existed here for providing

substantial relief to the Red Army on the eastern front by

launching a determined Allied thrust northwards through Italy.

SHAEF clearly ignored available intelligence showing conditions

to be ideal for an immediate and unopposed advance on Rome.

Instead, the military command waited until the Germans had

organised an effective defence and counter-attack. The New

Zealand and Indian contingents of the landing force took

particularly heavy casualties, with the enemy then retiring north

of Rome in good order. There the Germans established a new and

unyielding line in Tuscany where the Italian campaign would drag

on for at least another year, at a cost of many more courageous

Allied lives sacrificed on the altar of deception.[8]

The Battle of the Bulge

U.S. troops at the Battle of the Bulge.

A final debacle in the patterned distribution of epic

intelligence "failures" and unheroic command decisions occurred

in December 1944, when the invading force failed to anticipate

the December 1944 German offensive in the Ardennes -- the Battle

of the Bulge, where the Germans inflicted major casualties on the

Anglo-American armies and nearly halted the Allied advance in its

tracks. Field Marshal Albrecht Kesselring was later to reveal

that Germany's 10th Army, the defending force in Italy, was so

unprepared that it would have been virtually annihilated had the

Western Allies immediately advanced their attack once a

beach-head was established.[9]

With the command structure of the Allied Expeditionary

Force

thus masquerading as "liberators" while actually prolonging the

war, Churchill was busily engaged behind the scenes in

intervening persistently in the Anglo-American nuclear weapons

project. He continually spurred the Los Alamos scientists to more

vigorous efforts in producing an atomic bomb before the Russians

single-handedly won the war in Europe. Churchill could count on

the unwavering support of Roosevelt who was fully prepared,

hopeful even, to use the atomic bomb against Germany.[10] The Red Army's momentous

breakthrough into eastern Germany, and its inexorable advance on

Berlin, then in progress, threatened to turn into reality not

only the worst fears of Hitler but also those of the Western

leadership. Britain's Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden had in 1941

already warned that Russian prestige at the end of the war would

be so great that "the establishment of communist governments in

the majority of European countries would be greatly

facilitated."[11] Similar

fears had also been conveyed to Churchill by his South African

ally, General Jan Smuts, who complained in 1943:

"I have the uncomfortable feeling that the scale and

speed of

our land operations leaves much to be desired ... Almost all the

honours on land go to the Russians, and deservedly so,

considering the scale and speed of their fighting and the

magnificence of their strategy on a vast front. Surely our

performance can be bettered and the comparison with Russia

rendered less unflattering to us? To the ordinary man it must

appear that it is Russia who is winning the war. If this

impression continues, what will be our post-war world position

compared with that of Russia? A tremendous shift in our world

status may follow, and leave Russia the diplomatic master of the

world. This is both unnecessary and undesirable, and would have

especially bad reactions for the British Commonwealth."[12]

Similar fears had been expressed to Roosevelt in

Washington by

his Chiefs of Staff who warned the American president in August

1944: "The end of the war will produce a change in the pattern of

military strength more comparable ... with that occasioned by the

fall of Rome than with any other change during the succeeding

fifteen hundred years."[13]

The Destruction of Dresden

Neither Smuts nor the American Chiefs of Staff would

have been

aware, as Churchill and Roosevelt were, of the secret nuclear

weapons project then nearing completion, and which would

guarantee for them the achievement of post-war political goals in

Europe. The atomic bomb, however, had not yet been tested, and

with few urban dwellings left to set on fire in western Germany,

Churchill and the bomber barons needed another means by which to

demonstrate at close quarters to the Russians an uncontested

margin of military if not moral superiority over them. The fate

of Dresden was sealed. Although the city was only of very minor

importance to the overall German war effort, it lay conveniently

across the Red Army's direct line of advance to Berlin. Famous

for its china and architecture, Dresden was also the largest of

very few civilian areas remaining intact in the whole of

Germany.[14] It also

happened to be crowded with large numbers of civilian refugees

who had fled from bombing in other parts of Germany, its

population of 600,000 having more than doubled to 1,250,000.

Since January 26, 1945 special trains had delivered thousands of

evacuees to the city, most recently on the afternoon of February

12, while thousands more arrived on foot or in horse-drawn

carts.[15] What followed

was to be one of the most senseless acts of savagery ever known

to humankind.

In the early hours of February 14, Ash Wednesday, a

total of

778 RAF heavy bombers began the attack. The following day the

Americans attacked with almost as many aircraft again. They

somehow managed to overlook the fact that 26,000 Allied prisoners

of war were imprisoned in the suburbs of Dresden. When the last

of the bombers departed, the open spaces on the banks of the Elbe

were piled with the bodies of civilians who flocked to the river

in search of escape from the heat and then drowned. The bodies of

many others were glued to the surface of streets where the tarmac

had melted and then solidified as the firestorm engulfed 11

square miles -- an area much larger than that destroyed at

Hamburg. About 75 per cent of all property was gutted completely

as temperatures soared to around 1,000 degrees

Centigrade.[16] Apart from

the many victims it incinerated immediately, thousands more died

in air raid shelters as the firestorm sucked out oxygen which was

replaced with poisonous fumes. About 50,000 civilians were killed

-- around 10,000 more than those who perished in the Hamburg

firestorm, and 20,000 more than those killed during the entire

eight-months "blitz" on Britain. Countless numbers of people were

rendered homeless. Bomber Command casualties were negligible --

Germany's earlier loss of France to the Allied Expeditionary

Force had created a gaping hole in Hitler's early-warning radar

system, providing the RAF with unchallenged operational

omnipotence.[17]

Astonishingly, almost unbelievably, Dresden was attacked

again

on March 2, this time by the Americans alone. Mustang fighter

escorts machine-gunned fleeing civilians while the heavy B-17s

achieved the singular distinction of sinking a hospital ship on

the Elbe, filled with injured from the earlier raids.[18]

Aftermath of the 1945 bombing of Dresden, Germany by Allied forces.

Dresden did not contain any oil refineries or synthetic

oil

plants, unlike Brux to the south, or Bohlen, Ruhland and Politz

which remained untouched, to the north and west of the doomed

city. Nor did Dresden appear on any list of priority targets

issued weekly by the Combined Strategic Targets Committee. Any

military justification for the American and the British raids was

non-existent, damage in terms of "war production" being confined

solely to the German cigar and cigarette industry.[19] Nor did the destruction of

Dresden disrupt or delay the Red Army's continued, rapid advance

on Berlin from the east. This probably came as something of a

disappointment to Royal Air Force Marshal Sir Arthur Harris who had

issued briefing notes to Bomber

Command aircrews stating modestly that an "incidental" purpose of

the massed aerial attack on Dresden was to show the Russians,

then just a few miles from Dresden, "what Bomber Command can

do."[20] The inference to

be drawn from this is that Harris, at the behest of Churchill,

wished to convey to the Russians a vivid impression of the West's

overwhelming superiority in long-distance aerial bombardment and

the ability of British and American aircraft to demolish an

entire city in the space of just a few hours. Indeed, the

demolition of Dresden may be interpreted as an act of outright

intimidation stopping just short of direct military operations

against the USSR.

The destruction of Dresden had been recommended by

Churchill

"with the particular object of exploiting the confused conditions

which are likely to exist ... during the successful Russian

advance."[21] Before the

massacre, No.1 Group, Bomber Command, had been told during

pre-flight briefing that Dresden was to be bombed because it was

"a railway centre"; No.3 Group was duped into believing it would

be attacking "a German army headquarters"; No.6 Group was

misinformed that Dresden was "an important industrial area,

producing chemicals and munitions"; some squadrons were

deceptively assured that Dresden contained a Gestapo headquarters

and a large poison-gas plant; another Group was given the

impression that the bombers would be breaching the defences of a

"fortress city" essential to the Germans in their fight against

the advancing Russians.[22]

Whatever impression the Russians themselves might have

gained

from taking possession of a ruined city after having witnessed at

close quarters the destructive potential of the West's

long-distance bombers, this was probably not what the Red Army

had in mind when on February 4, 10 days before the Dresden

atrocity, it had conveyed to the Western Allies an urgent

request. The Red Army's Deputy Chief of Staff, Marshal Antonov

had specifically asked the Western Allies as a matter of urgent

priority to cripple the transportation system in eastern Germany.

The request was reiterated by Marshal Khudyakov, Chief of the

Soviet Air Staff. Both commanders urgently wished to prevent

enemy troop movements toward the eastern front, particular

reference being made by Khudyakov to the necessity of preventing

the movement by road and rail of German reinforcements from

Italy.[23] The request was

ignored. Dresden's crowded Dresden-Klotzsche airfield remained

unscathed, and the railway marshalling yards were similarly

spared destruction.[24]

Yet highly advanced and extremely accurate ground-attack

fighter-bombers and dive-bombers of the Anglo-American 2nd

Tactical Air Force, then dispersed at various airfields in newly

liberated Belgium, Holland and France, were readily available for

such a task. Armed with rockets, light bombs and heavy machine

guns, they had the easy capability to destroy German road and

rail communications and generally harass the German armed forces

deep in eastern Germany, without indiscriminately slaughtering

civilians. So under-utilised was 2nd Tactical Air Force during

these closing stages of the war that many of its aircraft were

left neatly parked next to unprotected runways in Allied occupied

territory where they were systematically destroyed on the ground

by remnants of the Luftwaffe. In just one such raid, 200

brand-new fighter-bombers of the 2nd Tactical Air Force were

destroyed at an airfield in Belgium, without any loss to the

enemy.

The highly-decorated 2nd Tactical Air Force commander,

Air

Chief-Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, was at the centre of a

bitter row with Britain's war planners over the merits of

combined tactical operations in support of Allied ground forces,

and "strategic" bombing conducted independently of combined

operations.[25] The

argument came to an abrupt end shortly after the destruction of

Dresden, when Sir Trafford was suddenly transferred to the Far

East. He was mysteriously killed when the aircraft that was

transporting him to India crashed in the French Alps. The exact

cause of the crash was never officially established.

Churchill warned him to be "very careful ... not to

admit that

we ever did anything not justified by the circumstances..."

As for events in eastern Germany immediately after the

Dresden

attacks, a blinding deference for the official version ensured

that the British Broadcasting Corporation reported on 14 February

that RAF and American bombers had "raided places of utmost

importance to the Germans in their struggle against the Russians,

notably at Dresden."[26]

One press officer at Supreme HQ Allied Expeditionary Force was

rather more forthcoming. In an "off the record" comment to war

correspondents, a certain Air Commodore Grierson confirmed for

the first time that the Allied plan in eastern Germany was to

"bomb large population centres and then to prevent relief

supplies from reaching and refugees from leaving them".

Associated Press swiftly cabled this news to the world at large.

The British censors reacted promptly, imposing a general

clampdown on the report.[27]

A massacre of such magnitude as occurred at Dresden,

however,

was difficult to hide indefinitely. During a debate in the House

of Commons on 6 March, the irrepressible Labour MP for Ipswich,

Richard Stokes, quoted the Associated Press report and a German

account which had appeared in the previous day's Manchester

Guardian. For the first time the expression "terror bombing" was

used in Parliament when Stokes complained:

"... you will find people in the Army and Air Force

protesting

against this mass and indiscriminate slaughter from the air ...

Leaving aside strategic bombing, which I question very much, and

tactical bombing, with which I agree if it is done with a

reasonable degree of accuracy, there is no case whatever under

any conditions in my view, for terror bombing."[28] Air Minister Sir Archibald

Sinclair left it to his deputy to reply to the debate. The

relatively obscure Under-Secretary assured the House: "We are not

wasting bombers or time purely on terror tactics. It does not do

the Honourable Member justice to ... suggest that there are a lot

of Air Marshals or pilots ... sitting in a room thinking how many

German women and children they can kill."[29]

Barely a week later on March 11, more than 1,000 of

Harris's

bombers carried out a heavy daylight raid on Essen, unleashing

4,700 tonnes of bombs which destroyed the city almost completely.

On 12 March, Dortmund became the target of the heaviest of all

raids in Europe so far when 1,107 bombers dropped 4,851 tonnes of

bombs on the already almost completely destroyed city.[30] German war production in the

period between January and the time of Germany's capitulation in

May was reduced by a mere 1.2 per cent.[31]

British Intelligence analysts would have been

well aware of this anomaly, given that Ultra had since 1944 been

providing them with a great deal of reliable information about

the German economy.[32]

While these final atrocities were taking place under the

twin

banners of "halting German war production" and "helping the

Russians", Churchill took great pains to obscure the fact that

the true fulcrum of air power lay neither with the Directorate of

Bombing Operations, nor with the Air Ministry or the Chiefs of

Staff, but solely with himself, Harris and a small cabal of

handpicked confidants. Official documents suppressed for many

years in the British archives but now available to researchers,

contain a reproachful minute dated March 28 from Churchill to the

Chiefs of Staff in which he deftly shifted all blame for the

terror bombing onto the hapless Chiefs of Staff. It was they,

according to Churchill, who had been principally responsible for

"increasing the terror, though under other pretexts."[33] In a worried "most private and

confidential" message to Harris, Churchill warned him to be "very

careful ... not to admit that we ever did anything not justified

by the circumstances and the actions of the enemy in the measures

we took to bomb Germany."[34]

The Red Army Strikes

Meanwhile, undeterred either by the measures of

Churchill and

Harris or by the circumstances and the actions of the enemy, the

Red Army continued its inexorable advance on Berlin's heavily

defended Reichstag, the symbolic heart of Nazidom. A few months

earlier, in January 1945 the Red Army and the Western Allied

armies were still approximately the same distance away from

Berlin, even though the disparity of enemy forces facing them was

heavily in favour of the Anglo-Americans. But by mid-April it was

the Red Army that arrived first in Berlin and began engaging its

defending troops in close combat. Street by street, building by

building, and finally staircase by staircase and cellar by

cellar, Soviet soldiers inched their way forward through the

city, taking heavy casualties in the fierce fighting. Finally, on

30 April a red flag bearing the hammer and sickle fluttered over

the Reichstag. Three days later Berlin fell. After more than

1,000 days and nights of war along a front thousands of miles in

length, as well as behind enemy lines in the occupied

territories, a victorious Red Army marched through the

Brandenburg Gate.[35]

The price paid by the Russians for defeating Hitler on

the

principal and decisive front of the war was enormous. Every

minute of the war the Russians lost nine lives, 587 lives every

hour and 14,000 lives every day, with two out of every five

persons killed during the war being Soviet citizens. Hundreds of

Russian towns and cities were devastated. Well over 20 million

Russians, half of them civilians, had died -- many more than the

combined total military casualties of Germany and the Western

Allies together.[36]

April 30, 1945: The

Soviet Victory Banner is raised over the German Reichstag in Berlin by

Red Army soldiers, shortly before the surrender of German forces in the

city and the

decisive victory over the fascists on May 9, 1945.

Notes

1. The figures are

from: Churchill, op cit, Vol IV, p.832; John Kennedy, op cit,

p.325; Paul Kennedy, op cit, pp.352, 354; Liddell Hart, op cit,

p.559; Zhukov, Vol II, pp.307, 344; US Army newspaper Stars

and Stripes, 15 May 1945.

2. John Kennedy, ibid.,

3. David Fraser, And We Shall

Shock

Them: The British Army in the Second World War, London:

Hodder and Stoughton 1983, p.348.

4. The account of the Arnhem

operation

draws on: Cornelius Ryan, A Bridge Too Far, London: Hamish

Hamilton, 1974; Ralph Bennett, "Ultra and Some Command

Decisions," Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 16, 1981,

pp.145-6; Richard Lamb, Montgomery in Europe 1943-45, London:

Buchan and Enright 1983, p.227.

5. PRO AIR 37/876, Arthur

Coningham,

"Operations Carried out by the Second Tactical Air Force between

6th June 1944 and 9 May 1945," p.23.

6. Ryan, op cit, p.454.

7. Bennett, op.cit, "Ultra and

Some

Command Decisions," p.135; Liddell Hart, op cit, p.536.

8. The account of the Italian

campaign

draws on: Martin Blumenson, Anzio: Philadelphia: Lippencott,

1963: Peter Calvocoressi and Guy Wint, Total War: Causes and

Courses of the Second World War, Harmondsworth: Penguin 1986,

pp.

511-2; Bennett, Ultra and Mediterranean Strategy, p.264; Fraser,

op cit, p.282.

9. Albrecht Kesselring, Memoirs,

London:

Greenhill 1988, p.193.

10. Leslie Groves, Now It Can

Be

Told, New York: Harper and Row 1962, p.184.

11. Elizabeth Barker, op cit,

p.236.

12. Letter from Smuts to

Churchill

dated 31 August 1943, quoted in Churchill, The Second World War,

Vol V, p.112.

13. Chiefs of Staff quoted in

Michael

Balfour, The Adversaries: America, Russia and the Open World

1941-1962, London: Routledge, Kegan Paul 1981, p.9.

14. SAO, Vol III, p.252.

15. SAO, Vol III, p.108; David

Irving, The Destruction of Dresden, London: Kimber 1963,

pp.88,

106-7, 256.

16. Hastings, op cit, pp.340-4;

Irving, Destruction of Dresden, pp.173-7, 206, 225-32, 236;

Middlebrook and Everitt, op cit, pp.663-4.

17. Richards and Saunders, Vol

III,

p.270; Irving, Destruction of Dresden, pp.173, 206; SAO,

Vol III, p.109.

18. Janusz Piekalkiewicz, The

Air

War 1939-1945, Poole: Blandford 1985, p.402.

19. See United States Strategic

Bombing

Survey, "Area Studies Division Report No.1", Washington:

Government Printers 1945, pp.235-40, Alan S. Milward, War,

Economy and Society, London: Allen Lane 1982, p.302.

20. Hastings, op. cit.p.342.

21. Churchill memorandum to Air

Minister Sinclair, 26 January 1945 quoted in SAO, Vol III, p.103;

Deputy Air Minister Sir Norman Bottomley to Harris, 27 January

1945 quoted in SAO, Vol III, p.103.

22. Longmate, op cit, p.335.

23. SAO, Vol III, pp.105-6.

24. Hastings, op cit, p.342;

Irving, Destruction of Dresden, pp. 148, 158, 206;

Piekalkiewicz,

op cit, p.402.

25. See PRO AIR 37/876, Air Chief

Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, "Operations Carried Out by

Second Tactical Air Force, 6 June 1944 to 9 May 1945".

26. Longmate, op cit, p.342.

27. SAO, Vol III, pp.113-4.

28. Hansard, House of

Commons, 6

March 1945.

29. Ibid.

30. Richards and Saunders, op

cit, Vol III, p.268.

31. Hastings, op cit,

p.337;

Piekalkiewics, op cit, pp.403-5.

32. See Hinsley, op cit,

Vol II,

Appendix 5, pp.671-2.

33. SAO, Vol III, pp.113-4.

34 Randolph S. Churchill and

Martin Gilbert, Winston S

Churchill, (8 vols), London: Heinemann, 1954-1988, Vol VIII,

p.259.

35. The capture of Berlin is

described

in Zhukov, op cit, Vol II, p.347 et al.

36. See generally Alexander

Werth, Russia at War

1941-1945, New York: Avon 1965; John Erickson, Stalin's War

With Germany, (2 vols) London: Grafton, 1985 where individual

campaigns are listed at Vol II, p.1181. Total losses of the

German Wehrmacht were 72 per cent of its officers and men. Most

died on the Soviet-German front.

Stan Winer is an international journalist with 30

years'

experience specialising in military-political and geo-strategic

affairs. His articles have appeared in a wide range of specialist

journals, newspapers and periodicals around the world. He has

also worked for the information departments of various United Nations

agencies.

(To access articles individually

click on

the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|