|

No. 20 |

September 9, 2021 |

|

50th Anniversary of the Attica Prison Uprising ò Attica Means Fight Back! Close Attica Down Now! ò Prisoners Condemn Slave Labour in the Prisons - Attica Is All of Us - - John Steinbach -

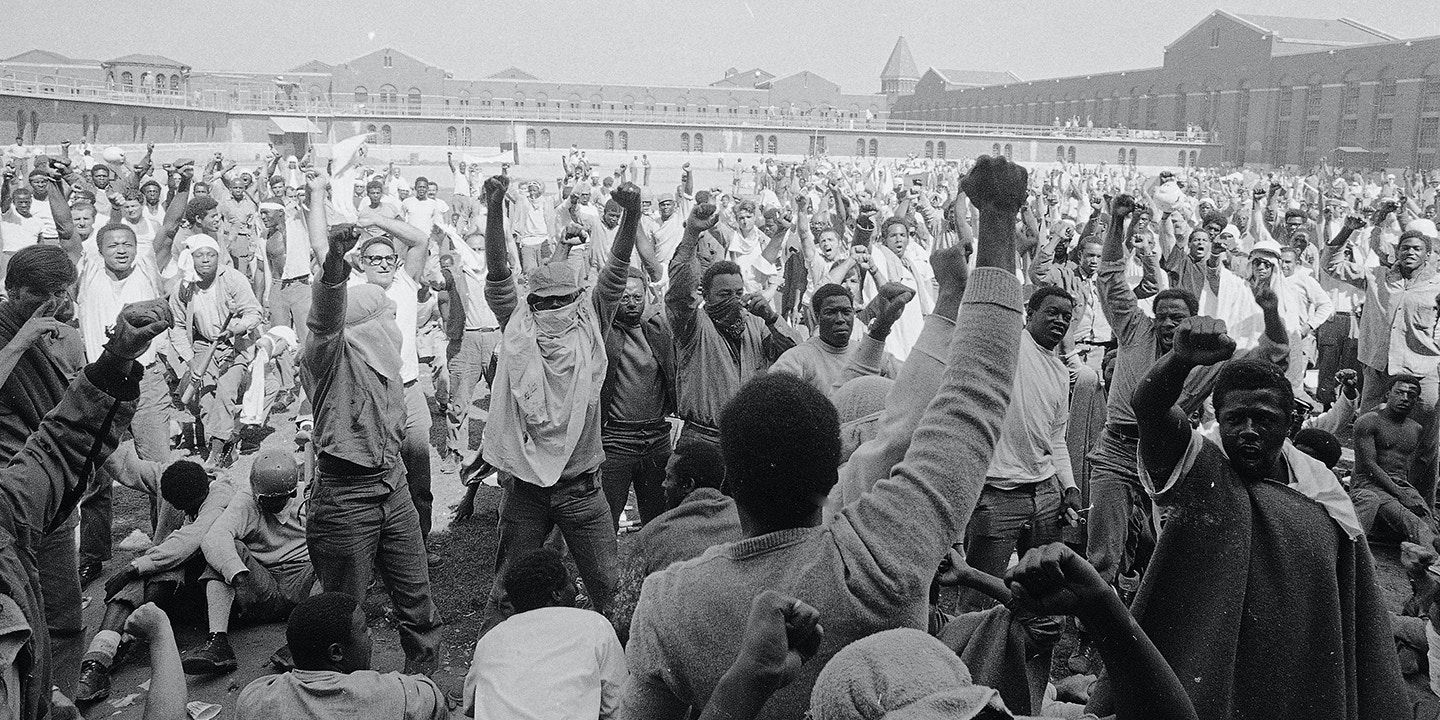

50th Anniversary of the Attica Prison Uprising Attica Means Fight Back! Close Attica Down Now!

TML is dedicating this supplement to the Rebellion at the Attica Maximum Security Prison in upstate New York which started on September 9, 1971 and ended with the brutal massacre conducted by New York State Troopers sent in by Governor Nelson Rockefeller on September 13, 1971.

Our thoughts go out to Dacajeweaiah who passed away in 2013 from all the trauma he experienced throughout his life and to all the Attica Brothers on this occasion as well as to all those families, resistance fighters, justice-seeking lawyers and advocates for those incarcerated by the U.S. prison system. They have fought and continue to fight to end this brutal racist and inhuman system of injustice which prevails in the United States. They contribute enormously to the creation of a society which affirms the rights of all without exception. Their experience is proof that Our Security Lies in the Fight for the Rights of All. With our deepest respects, we dedicate this issue of TML Supplement to all the men, women and youth valiantly fighting to abolish the racist U.S. prison system and those in other countries including Canada.[1] Join the work of Attica Is All of Us! For information click here. |

|

|

By all accounts, the negotiations were a tremendous success. The Attica Brothers' demands were reasonable and even the hostages, whom the media asked, and in the process confirmed were well cared for, were vocal in their support of state officials coming to an agreement with the men in D Yard. As documents uncovered in 2016 made clear, however, the Governor of New York, along with the members of law enforcement, had together been mobilizing to retake Attica with brutal and ugly force since day one of the uprising. As soon as they had the opportunity to do so, they did just that.

On the cold, rainy, morning of September 13, 1971, and after first dropping canisters of CN and CS gas that literally mowed the men in D Yard down as it caused them to choke and stumble blindly with tears streaming from their eyes, the State of New York then sent many hundreds of NY State Troopers, as well as corrections officers and other heavily-armed members of law enforcement, into Attica with their guns blazing. Within 15 minutes, the buckshot and bullets from their rifles, handguns, personal weapons, as well as countless state-issued weapons -- some of it intended for big game and some actually outlawed by the Geneva Convention--had felled 128 men, and had killed 39 of them. The State of New York, rather than negotiate a peaceful settlement at Attica had shot and killed scores of men -- prisoners and hostages alike.

Stunningly, state officials then stepped outside of the prison walls

and told the throngs of people assembled there, including media outlets

from all over the country, that something entirely different had just

taken place. The prisoners, they said, had just killed, the hostages.

They had not

only slit their throats, but they had also brutally castrated one of

them. This outright, and utterly uncorroborated lie was printed as the

factual account of what had taken place at Attica on the front page of

the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and most

tragically, it is

the story that went on the AP wire, which meant that it is the story

that landed on the headlines of smaller newspapers in other cities and

small towns across America.

The brutal massacre by State Troopers at Attica Prison is met with an immediate

outcry from the people, who protest at the New York State

Legislature in Albany that same day.

New York City, September 13, 1971

Buffalo, New York, September 13, 1971

New York City, September 18, 1971

Immediate Aftermath

This horrific lie told by the State of New York, would not only, in that moment and thereafter, turn countless Americans against the idea that prisoners should have basic rights in this country, but it would also unleash what a later judge would call "an orgy of brutality" against the wounded, terrified men inside of Attica -- men who now were at the complete mercy of troopers and corrections officers eager to make them pay for ever having dared to rebel in the first place.

In the days, weeks, and months after state officials had retaken full

control of Attica, the torture of the men inside continued, a

sophisticated and far-reaching cover up of the murders, woundings, and

these very acts of torture, was fully in motion, myriad investigations

of what had just

happened at Attica were in process, and activists as well as lawyers

from across the country were doing everything in their power to make

sure that the men inside were getting the medical care and legal

representation they desperately needed.

In the days, weeks, and months after state officials had retaken full

control of Attica, the torture of the men inside continued, a

sophisticated and far-reaching cover up of the murders, woundings, and

these very acts of torture, was fully in motion, myriad investigations

of what had just

happened at Attica were in process, and activists as well as lawyers

from across the country were doing everything in their power to make

sure that the men inside were getting the medical care and legal

representation they desperately needed.

Although there was an official State of New York Investigation into why the Attica uprising had happened and, most pressingly to the public, why so many people had been shot, wounded, harmed, and killed, it has later become clear that this investigation was compromised from the very beginning. From the fact that the first investigators were from the ranks of the New York State Police -- the same body, and in some instances, the very same troopers -- who had shot and killed people on the day of Attica's retaking, to the fact that evidence of trooper and correction officer shootings was never collected, was "lost," was tampered with, and even burned, there was little chance that real justice would be done. Indeed, despite the fact that every single death at Attica on September 13, 1971 was at the hands of a law enforcement bullet, rather than a single trooper or CO ever standing trial, fifteen months after the massacre, the state, to disguise its villainy, charged 62 Attica Brothers, in 42 indictments, with 1,300 crimes.

Fighting the Indictments

But the history of Attica is a history of resistance, and thus, the story did not end here. Indeed, even from their cells in segregation, the indicted Attica Brothers fought their charges. From the moment the indictments were handed down, young lawyers and law students from around the country descended on upstate New York to form one of the most important grassroots legal defense efforts in American history alongside them, and community activists from around the county, and world, mobilized to support their effort as well. Thanks to this Herculean and collective effort, the Brothers ultimately prevented the State of New York from railroading them in the criminal trials. Thanks as well as to the bravery of a whistleblower inside of the Attica Investigation willing to point to the coverup at its core, in 1976, Governor Hugh Carey, was forced to vacate the remaining criminal indictments, disband the Attica grand juries, and even to grant pardons and commutations.

Holding the State Accountable

Protest in Buffalo, 1974

|

At that point, the State of New York would have liked nothing better than for the Attica Brothers simply to have gone away. To be sure, no trooper would ever be indicted now that the "book on Attica" would be "closed," according to Governor Carey. But since no prisoner faced indictment anymore either, he hoped, perhaps bygones could be bygones. But for the men at Attica who had experienced a trauma of the degree they had -- not just having been shot, some of them 6 and 7 times, but then stripped, assaulted, forced to run gauntlets, to endure Russian Roulette, burns, torture, and then being indicted -- to have all of that trauma denied? That was asking far too much.

In fact, the surviving Attica Brothers and next of kin of the dead had already commenced a federal civil rights class action lawsuit against Rockefeller and state prison officials back on September 13, 1974. Although they had been forced to wait to proceed with that suit until the criminal cases filed against them were resolved, proceed they eventually were determined to do. It would take a full 29 years -- decades of state attempts to silence them, hide documents, obfuscate what really had happened and who was responsible, and to protect prison and police officials from the most egregious of the actions they had carried out against fellow human beings. Eventually, however, the Attica Brothers were able to tell the court what had happened to each and every one of them at the hands of the State of New York, and the State of New York was forced to pay damages for the orgy of brutality it had unleashed against them.

Attica: The Next Chapter

Today the Attica State Correctional Facility remains open. Attica is still a maximum security prison. Attica is still a horrific and brutal place. Given the overcrowding of today's mass incarceration moment, given the increased length of sentences people now serve compared to back in 1971, and given the restrictions that have been placed on prisoners' ability to challenge the terrible conditions they endure (because of terrible pieces of legislation such as the Prison Litigation Reform Act), some would even say that conditions are worse there now than they were back in 1971.

Either way, Attica is a trauma site. Attica is a site of torture. Attica is no place for human beings now, any more than it was in 1971.

And, so, today, 50 years after the uprising at Attica we call for the immediate closing of this institution.

ATTICA MEANS FIGHT BACK!

(Photos and illustrations: Prisoners Solidarity Committee, Attica News, Project NIA, Committee to Free Dacajeweiah, J. Stanthorp, New York City Archives.)

Dacajeweiah: Childhood and Youth

Excerpt from John Steinbach's hommage to Dacajeweiah at a memorial service held in Chase, BC in March 2013.

When Dac was just 7, living in Buffalo, NY, his father Savario

Boncore, a painter for U.S. Rubber, was forced along with 10 co-workers

to enter and spray paint, without respirators or other protections, a

large storage tank. All 11 men perished, leaving Dac and his three

sisters fatherless, and

his mother destitute. Dac and his sisters were forcibly removed from

their mother's care, and institutionalized in orphanages, group homes

and foster homes. According to Dac, he refused to submit to this

oppressive and degrading environment and soon was branded "incorrigible"

by the authorities.

When Dac was just 7, living in Buffalo, NY, his father Savario

Boncore, a painter for U.S. Rubber, was forced along with 10 co-workers

to enter and spray paint, without respirators or other protections, a

large storage tank. All 11 men perished, leaving Dac and his three

sisters fatherless, and

his mother destitute. Dac and his sisters were forcibly removed from

their mother's care, and institutionalized in orphanages, group homes

and foster homes. According to Dac, he refused to submit to this

oppressive and degrading environment and soon was branded "incorrigible"

by the authorities.

At age 17 and freshly freed from reform school, Dac found himself homeless and sleeping on the street with the cruel Buffalo winter fast approaching. Desperate with cold and hunger, he decided to rob a store. Of course, he was quickly apprehended by the store-owners who fed him a sandwich while waiting for the police. Despite it having been his first felony conviction, Dac was sentenced to four years in prison for attempted robbery.

Two hard years at Elmira State Reformatory made Dac determined to resist the brutal, racist New York prison system. It was at Elmira that Dac first became acquainted with activists in the Anti-War, Native American, Black Liberation and Puerto Rican Independence movements, and began to develop the political consciousness which informed his activism over the next 30 years. Dac recalls, "We began to realize that we were victims of a system that didn't meet our needs and so we started entertaining a lot of ideas about revolutionary resistance in order to overthrow this ruthless system." At 19, just months from his scheduled parole and in order to be released nearer to his home, Dac made the fateful decision to request transfer to the notorious U.S. Gulag called Attica Prison.

Attica

Attica was notorious even among the brutal, degrading system of state prisons of the 1970s. The prison itself was grotesquely overcrowded and prisoners were forced to subsist on a mere 62 cents per day. Despite the fact that a large majority of prisoners were people of color, the prison staff were entirely white and often openly racist. It was reported that the warden himself was an active leader in the local Ku Klux Klan. Assaults and murders of prisoners were a common occurrence. Although just 19 as he entered Attica, Dac, hardened by two years at Elmira, was determined to remain unintimidated. Little did he know that just 17 days later Attica would become a literal hell on Earth.

George Jackson was a hero to many revolutionaries, including Dacajeweiah. A prisoner at San Quentin in California, he had written two important radical books, and was considered a major spokesperson for Black Liberation and prisoners rights. When George Jackson was set up and assassinated by the authorities at San Quentin, the shock waves spread throughout the U.S. prison system. At Attica, the 1,200 inmates went on a solidarity hunger strike which both infuriated and frightened the guards.

The following day, in an attempt to create dissension among the prisoners, the guards tried to provoke a race riot by pitting a black against a white prisoner. When the white prisoner protested in defence of his black brother, both were ordered into the hole. The stage was set for rebellion.

Dac recalls walking down the hall with Sam Melville, a leader of the Weather Underground, when they encountered the guard captain. Sam and a Black leader confronted the captain about why the others were locked up. When the captain made excuses, he was knocked down and Dac bellowed, "Let's take the place! This is it! Let's riot!" Suddenly all 1,200 men started rioting and shortly controlled the prison. One of the guards, William Quinn was accidentally injured during the initial insurrection and died several days later. His unfortunate death was later to play an important part of Dac's story.

The rebellion lasted five days and from the beginning the 1,200 inmates organized themselves into committees and showed the world the true face of democracy. According to Dac, "For the very first time, people around the world were starting to finally hear about what was really going on within America's penal system." The 50 prison guard hostages were dressed in prisoners garb and used in negotiations. The State agreed to 28 demands, but refused the most critical & non-negotiable one; blanket amnesty for all involved. There was a standoff and although negotiations were ongoing and all the hostages unharmed, Governor Nelson Rockefeller gave the word to storm Attica.

When the decision came down, over 1,000 heavily armed state troopers were diverted from an impending attack on Mohawk Indians on Onandaga Territory, who were attempting to block an extension of Highway 81 through Sacred Indian land. (Some Mohawk warriors later reported to Dacajeweiah that during the Attica massacre the drums hanging on the Longhouse wall started drumming an Honor Song with no one playing them). It had been raining that day, and Dac describes waves of red raincoated state police coming in from above, as a helicopter hovered over the courtyard demanding that the hostages be released.

Suddenly the helicopter released several CN4 poison gas canisters, outlawed by the Geneva Convention, and, simultaneously, the attacking police opened fire. As many as 15,000 rounds of live ammunition were fired that day, and when the smoke cleared 43 were dead, 11 guards and 32 prisoners, all killed by police fire; over eighty were wounded. Dac describes prisoners begging for their lives as they were shot in cold blood. He talks about prisoners being forced into latrine trenches filled with urine and feces, being marked with an X and then shot in the back. Dac himself was grazed by three bullets and would have been killed except for a gun misfire. When all is said and done, Attica was a criminal massacre, but Dacajeweiah was the only person ever convicted and punished.

A year and a half after Attica, Dacajeweiah was convicted of the

murder of guard Quinn, and sentenced to 20 years to life. (He would have

received the death penalty except for the fact that the Supreme Court

had just declared capital punishment illegal.) While out on bond prior

to his conviction,

Dac, for the first time, became involved in the organized movement. He

traveled to Genienkeh, a Mohawk survival camp, where he became a member

of the Mohawk Warrior Society. In his book, Dac tells a story about how

the Mohawk Warriors, dressed in white sheets for snow camouflage, got

the drop on

several hundred state troopers and forced them to withdraw. It was at

Genienkeh that Dac met his first wife Alicia, the mother of his sons

John and Nicosa. Ultimately, Dacajeweiah spent five long years in prison

for the murder of Quinn.

Actions to free political prisoners from the Attica Uprising and other struggles, in Buffalo, NY (1974) and New York City (1977).

For a copy of Dacajeweiah's autobiography, send check or money order for $40 (includes GST, shipping and handling) to:

|

In all, 61 men were indicted for the Attica uprising. Rockefeller

became Vice President of the U.S. and Hugh Carey became Governor of New

York. As time passed, it became more and more difficult to ignore the

atrocities committed at Attica and the political heat became unbearable.

Nelson

Rockefeller was facing confirmation hearings for Vice-President, but the

Attica massacre stood as a major blemish on his political record.

Rockefeller would order Anthony B. Simonetti, head of the New York

Bureau of Criminal Investigation, to cover up the murders by state

police at Attica, then

under investigation by a second Grand Jury. One of the massacre

investigators, Malcom Bell who later wrote the best-selling Attica

expose Turkey Shoot, refused to be a part of this blatant jury

tampering and ultimately blew the whistle to the New York Times. The

Times sat on Bell's article for a

full two months, until after Dacajeweiah's conviction. When the story

finally broke, it created a major scandal. In an effort to put a lid on

this embarrassing and politically devastating fiasco, Governor Hugh

Carey ordered that all charges rising out of Attica, including probable

charges against

the police, were to be dropped. Dacajeweiah was the only one left

imprisoned.

Former Attorney General Ramsey Clark replaced William Kunstler as Dacajeweiah's attorney and approached Carey, pointing out the injustice of Dac's continued incarceration. Carey ordered Dac's release, but not before the prison authorities and state police made several attempts on his life. Dac describes several assassination attempts, including being driven to a parole hearing by detectives over back roads at speeds of over 100 mph while pursuing cops peppered them with bullets. When Dac appeared before the Parole Board, and for the first time in New York history, the Board overruled a Governor's clemency decision and ordered him held for two more years. Sixteen prisons later, including a stint at Sing Sing prison, and after a brief reincarceration for an alleged parole violation, Dac was finally freed for good in 1979.

(In Loving Memory of John Boncore Hill "Splitting the Sky" Dacajeweiah (Dac) by John Steinbach, Memorial Service, March 23, 2013. Phtotos: LNS, Committee to Free Dacajeweiah, J. Stanthorp.)

(To access articles individually click on the black headline.)

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca

We

are providing the history as recorded by Attica Is All of Us

Coalition, as well as an excerpt from the Memorial delivered by John

Steinbach on Attica Brother Dacajeweiah (Splitting the Sky) at his

funeral in 2013. Dacajeweiah was put into the U.S. prison system and

ended up at Attica where he took part in the rebellion. He was subsequently

condemned to life in prison on false charges that he killed a prison

guard during the uprising.

We

are providing the history as recorded by Attica Is All of Us

Coalition, as well as an excerpt from the Memorial delivered by John

Steinbach on Attica Brother Dacajeweiah (Splitting the Sky) at his

funeral in 2013. Dacajeweiah was put into the U.S. prison system and

ended up at Attica where he took part in the rebellion. He was subsequently

condemned to life in prison on false charges that he killed a prison

guard during the uprising.

One can't understand Attica, and all that happened there in 1971,

without remembering what had been taking place in the nation as whole

-- on the streets as well as in prisons -- throughout the previous decade.

From states like California, New York, and Mississippi; and cities like

Chicago, Newark

and Detroit; and in prisons as far flung as Angola and Auburn, as well

as in urban jails like Wayne County, Cook County, and LA County, people

from across the country had been mobilizing to fight oppression,

injustice, and inequality. Time and again, however, these determined

grassroots demands to

end this country's most racist and sexist practices and policies were

met with a most violent response from state officials. Be it in Selma in

1965, or Chicago in 1968, or Orangeburg in 1969, or at Jackson State

and Kent State in 1970, those with power in this country made clear to

anyone who might

dare to change this nation for the better, that doing so might well mean

risking your life.

One can't understand Attica, and all that happened there in 1971,

without remembering what had been taking place in the nation as whole

-- on the streets as well as in prisons -- throughout the previous decade.

From states like California, New York, and Mississippi; and cities like

Chicago, Newark

and Detroit; and in prisons as far flung as Angola and Auburn, as well

as in urban jails like Wayne County, Cook County, and LA County, people

from across the country had been mobilizing to fight oppression,

injustice, and inequality. Time and again, however, these determined

grassroots demands to

end this country's most racist and sexist practices and policies were

met with a most violent response from state officials. Be it in Selma in

1965, or Chicago in 1968, or Orangeburg in 1969, or at Jackson State

and Kent State in 1970, those with power in this country made clear to

anyone who might

dare to change this nation for the better, that doing so might well mean

risking your life.  As frustrations grew, a group of prisoners calling itself the Attica

Liberation Faction decided to issue a Manifesto of Demands to the

Commissioner of Corrections, Russell Oswald. But he also did little to

address what was clearly a growing crisis in this facility. Then, on

August 21, 1971 news

broke that California prison activist George Jackson had been murdered

by guards in San Quentin. This, for so many at Attica, changed

everything.

As frustrations grew, a group of prisoners calling itself the Attica

Liberation Faction decided to issue a Manifesto of Demands to the

Commissioner of Corrections, Russell Oswald. But he also did little to

address what was clearly a growing crisis in this facility. Then, on

August 21, 1971 news

broke that California prison activist George Jackson had been murdered

by guards in San Quentin. This, for so many at Attica, changed

everything.