November 16, 1885

137th Anniversary of the Hanging of Louis Riel

Infamous Day in the History of Canada

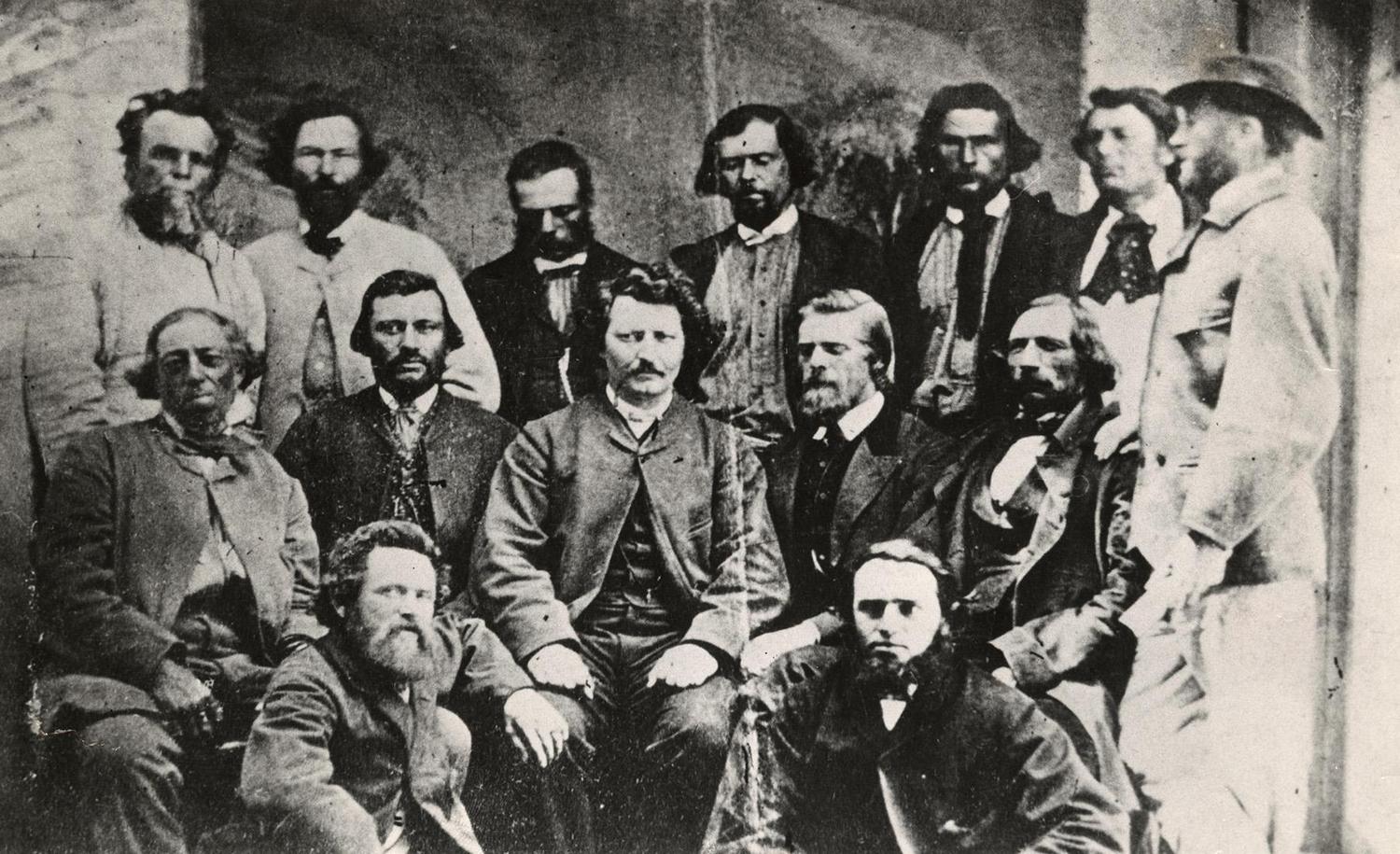

Métis leader Louis Riel (centre) with councillors of the Métis Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia.

“When the Government of Canada presented itself at our doors it found us at peace. It found that the Métis people of the North-West could not only live well without it … but that it had a government of its own, free, peaceful, well-functioning, contributing to the work of civilization in a way that the Company from England could never have done without thousands of soldiers. It was a government with an organized constitution whose jurisdiction was more legitimate and worthy of respect, because it was exercised over a country that belonged to it.” — Louis Riel, 1885

On November 16, 1885, the British colonial power executed the great Métis leader Louis Riel. Riel had been charged and found guilty of high treason after the Métis were defeated at the Battle of Batoche in May of that year. The execution of Louis Riel was intended as an assault on the consciousness of the Métis nation, but was unsuccessful in putting an end to their fight for their rights and dignity as a nation. The struggle of the Métis to affirm their right to be and exercise control over their political affairs continues to this day.

The two great uprisings of the Métis — the Red River Uprising (1869-1870) and North-West Uprising (1885) — were not isolated events but took place at a time when the Indigenous nations and the Quebec nation were also striving to affirm their nationhood, and at a time of revolutionary ferment in Europe. The Métis’ uprisings represented a response to the colonial project that sought to reproduce the British state in North America and block the legitimate aspirations of the nations that comprised Canada.

The British North America Act of 1867 and the federal government’s purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869-1870, juxtaposed with the decline of the traditional Métis economy based on the buffalo hunt, forced the Métis to engage in a power struggle with the colonial authorities and negotiate Manitoba’s entry into the Confederation after the establishment of a Legislative Assembly. The spirit that motivated Riel and the members of the provisional government at the time is contained in the Declaration of the Inhabitants of Rupert’s Land and the Northwest that affirms the sovereignty of the Métis over their lands. The latter also refused to recognize the authority of Canada, “[…], which presumes to have the right to come and impose on us a form of government even more incompatible with our rights and our interests […].”

Royal Canadian Mounted Police, successor to the North-West Mounted Police, continues crimes against Indigenous peoples in the present. (A. Deschênes) |

The Manitoba Act, which established that province, was voted on and passed in the federal Parliament in May 1870. The government wasted no time in exerting control over its new territory as evidenced by the Wolseley military expedition later that year — which led to Riel fleeing to the U.S. for fear of his safety — the creation of the North-West Mounted Police (1873) and the Indian Act (1876). Prime Minister John A. Macdonald championed the colonization of the west and the development of agriculture with the national policy he had been promoting since 1878. With the help of the Oblates (lay members of the Catholic Church affiliated with a monastic community), the authorities sought to settle the Métis and force them to adopt an agricultural lifestyle. Facing an existence within this rigid framework and under pressure from land speculators, some Métis sold the land that had been granted to them and settled in Saskatchewan.

This was a period when nationalism was in the air. The events in Manitoba alerted Quebeckers to the fragility of the Métis’ situation, while the abolition of the teaching of French in New Brunswick in 1871 indicated the need for organization. National organizations to defend the rights and interests of Francophones, such as the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society, spread across the continent with the waves of migration from the St. Lawrence valley. The National Convention of Montreal in 1874 and the Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebrations in Quebec in 1880 and Windsor in 1883 brought together delegations from all of French America in a strong show of the vitality of the “French-Canadian family.” Acadians held their first convention in 1881 where they held a celebration and adopted a national doctrine.

Métis leaders, under the sway of the Church at that time, did not rock the boat. In the aftermath of the Red River resistance, the Saint-Jean-Baptiste society of Manitoba was founded in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba. Its vice-president was none other than Louis Riel. This association included in its infancy as many French Canadians as Francophone Métis.

However, aware of their distinct identity, Métis leaders wished to forge their own nationalism. Riel would come to articulate a Métis nationalism, with its own holidays and national symbols. This process would culminate in the creation of the Métis National Council at Batoche in September 1884, to promote the development of their political consciousness.

The Métis once again took up arms to affirm their nationhood and right to be in the North West Rebellion of 1885. For three days between May 9 and May 12, 1885, 250 Métis fought valiantly against 916 Canadian Forces at the Battle of Batoche but were defeated and Riel surrendered.

Louis Riel’s address to the jury in Regina courtroom, July 1885.

Macdonald and his cabinet took a hard line with respect to Riel and his compatriots. Riel was tried in Regina over five days in July 1885. After half-an-hour’s deliberation he was found guilty of treason by the jury, which recommended mercy. Nevertheless, Judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him to death. From September 1885 to October 1886, Riel and several of his comrades, all Indigenous, would be condemned to hang.

While times have changed, the Canadian state has inherited the colonial power and it persists in the aim of negating the nationhood of the Métis, Indigenous nations and Quebec. The proud history of the Métis and their fight to affirm their rights and nationhood is not some historical artifact gathering dust, but continues to gleam brightly in the light of the present day. The fight to affirm rights that belong to people by virtue of their being human is precisely the fight for modern, human-centred arrangements. Louis Riel’s life epitomized the fight for the recognition of rights on a modern basis.

Louis Riel’s life is an important legacy that is as relevant as ever at this time when the Canadian state is doing its utmost to negate the rights of the Métis, Indigenous nations and the Quebec nation, as well as the workers, women, youth, national minorities and all the collectives in the society, all in the name of security, balance, austerity and other phony high ideals.

(Based on an article by Marc-André Gagnon published in Chantier politique no. 32, November 18, 2013. Translated from the original French by TML Weekly. Photos from public archives.)

|

|

[BACK]