In the News June 9

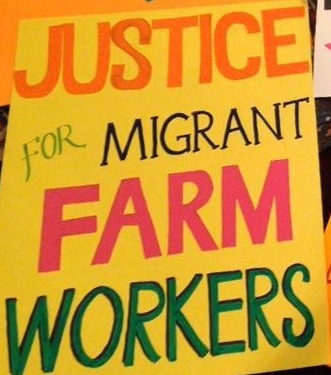

Justice for Temporary Migrant Workers

Why a Constitutional Challenge at This Time?

A matter of great concern today is seeking justice for migrant workers, a field where the violation of basic human rights is pronounced and includes not only total disregard for the human person but also human trafficking.

The respect of the fundamental rights of migrant workers must be the same as for all other workers in Quebec and in Canada. They are part of one and the same working class and they contribute immensely to the country’s economy, culture and the well-being of all. We need them just as they need us and as our colleagues, friends and neighbours, their fight is also our fight. Furthermore, when they are deprived of their rights and wellbeing, it pushes downward pressure on the working conditions of all workers – including those working alongside others placed by the state in a legal condition of employer servitude.

Over the last decades, along with dozens of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the Association for the Rights of Household and Farm Workers (RHFW) has attempted to educate teams in the federal government ministries of immigration and labour about the serious problems posed by what are called closed work permits which keep migrant workers bound to one employer, and their possible solution.

“At present, the Canadian government is perfectly aware of the effects of the condition of servitude imposed on temporary foreign workers through employer-specific work permits,” says RHFW Executive Director Eugénie Depatie-Pelletier.

“At present, the Canadian government is perfectly aware of the effects of the condition of servitude imposed on temporary foreign workers through employer-specific work permits,” says RHFW Executive Director Eugénie Depatie-Pelletier.

“Furthermore, the government is also aware of decent alternative measures to managing shortages through migrant and immigrant labour. The federal government knows of these alternatives because it is already applying them. Admission under permanent status is already being offered, as is admission under open work permits – in both cases for annual, pre-determined quotas and workers with different types of skills.

“In Quebec, young people from France in particular have access to the labour market as free foreign workers. They have access to a system of employment that favours the obtention, or at least the search for, decent working conditions. They have access to a system of employment that could easily no longer be an exception for privileged foreign workers but the rule. That rule would ensure in Canada a free labour market, whereby employers would face healthy competition as to the recruitment and retention of employees, a rule demonstrating that our society takes fundamental rights seriously, that would allow for respect by the state for the dignity of all workers within the country, even those here under temporary legal status.”

Despite all this, Eugénie points out, “the government’s position is […] the continuation of a long tradition.”

In her view, one way to definitively dismantle the system of unfree labour is to challenge it before the courts.

“… [I]n Canada we have a constitution that enables us to invalidate state actions that violate, without due justification, a right or a fundamental freedom protected by the constitution for both citizens and non-citizens.”

She adds that since the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a number of constitutional challenges have constituted an efficient and lasting vehicle for the advancement of the rights of persons marginalized by the state, such as the right to choose one’s residence, to medical assistance in dying, to medicinal marijuana for those in pain and to abortion.

More precisely, she points out, “these are court battles that have been won by virtue of the constitutional right to liberty and security of the person. Notably, it’s on the basis of that right that we believe that restrictions to changing one’s employer must be declared invalid and inapplicable, as it protects the implicit right to change employers and to not be held in conditions of servitude.”

Eugénie describes the conditions under which these temporary foreign workers are forced to live as “a state system that for workers unjustifiably restricts their fundamental right to physical and psychological security, to obtain justice, to freedom.

“Non-freedom on the labour market creates a system that provides employers with a very tempting power to use to illegally extract the maximum from the employee as quickly as possible, irrespective of the impact on that worker’s body, spirit, or family. It creates a system that imposes upon all employers concerned not only obedient workers and therefore flexible to the extreme, but in addition creates workers who are easily disposable, who can be relatively easily removed from the legal labour market in the case of non-obedience, complaints, work accidents, occupational disease or even inconvenient parenthood.

“This creates a system of abuse that can and does become the norm, that for workers creates an obstacle to the general exercise of their rights, a system that avoids the application of the rule of law, that cannot be justified within a system that claims to be free.”

“The human dignity of all household and agricultural workers must be respected, even when they are employed under temporary legal status,” Eugénie says. “The right to leave one’s job and to change employers must be recognized as fundamental. It is more than time that the human and social costs associated with maintaining these workers within such conditions of servitude are evaluated.

“Our recourse has the potential to give rise to a major and lasting change of paradigm. Our recourse is necessary. We have the legal framework, we have the arguments, we have the evidence. We’re ready … to fight!”

Workers’ Forum, posted June 9, 2022.

|

|