Edmonton Exhibition of Works by Artist Mary Joyce

Culture of Resistance Art Exhibition – A Review

– Marina Allemano –

The review below of Mary Joyce’s show, Culture of Resistance, was written by Dr. Marina Allemano, Retired Lecturer, Department of Modern Languages & Cultural Studies, University of Alberta, and an author, translator and literary critic.

When you enter Galerie Cité in Edmonton where Mary Joyce’s show “Culture de résistance” is on display, the first impression is a combination of energy, vibrancy, sensuousness and beauty, not the least due to the large-scale red felt piece suspended from the 24-feet high ceiling in the atrium.

What is the idea of the huge square of a delicious rosy-red hue? It measures 26 feet on each side and hangs like a tent or a sail during a storm, the four corners secured to the balusters. Although inert, the draping suggests motion which is indeed one of the leading motifs in the exhibit. The artist explains in her accompanying text that the large square was inspired by the small one-inch red felt square worn by Québec students in 2012 as a badge to protest tuition hikes and student poverty as expressed in the wordplay “carrément dans le rouge” (squarely in the red).

In the atrium the hanging is not within reach from the ground but forces the viewer to look up and experience the seemingly gravity-defying structure that connotes flight and expansion — “Resistance is everywhere” — but also as shelter and soft intimacy should the tent take landing. The idea of safety, stability and strength is further conveyed in the symbol of the eight over-sized brass safety pins attached to the cloth signaling the ordinary safety pins used to attach “les carrés rouges” to the protesters’ coats.

In addition to the red hanging, thirty-six paintings and prints are an invitation to celebrate and reflect on resistance as a fundamental human behaviour when faced with oppressive legislation and governance that harm and even destroy the lives and rights of the people. The safety-pin motif with its characteristic coiled shape is repeated in several of the works, veiled or distinct, pins closed or open, creating new and exciting compositional forms.

The artist documents specific acts of resistance, many of large public demonstrations and protests in Canada and abroad. A large image (oil-on-wood 30×30″) of a march in the town of Alma, Québec, stands out, depicting a historic action against the lockout at the Rio Tinto Alcan smelter in March 2012. Dot-like non-individuated figures in the far distance snake their way from the industrial site in the horizon to the front of the painting where distinct faces and figures of families come into view as if they were about to step out of the frame. As an onlooker I felt the urge to engage with these folks and hear their stories.

Documentation and skillful art are inseparable in this exhibit. Speaking to other gallery guests at the official opening, I learn that the all-time favourite painting is the large painting (oil-on-canvas 48×48″) titled “Indian Farmers Flowers Shower” that pays homage to the drawn-out struggle continuing from 2020 through 2021. Seldom have a tractor and a truck looked more attractive, and protesting farmers more dynamic, than in this piece of art. The palette of candy-like pastel colours and sprinkles of floating flower petals have much to do with the energy expressed, and once again the composition brings the moving vehicles and figures forward directly into the viewer’s space. Because the events portrayed are particular and historical, it is helpful to read the gloss accompanying the pieces to appreciate the moment captured: “On the borders of New Delhi, farmers have camped for months in protest against PM Modi. Many are widows of farmers who could not withstand the hardships.”

Other works in the show are more intimate such as the figurative painting (oil-on-wood 30×24″) “For Our Daughters 1989-2008,” showing a group of five women chatting, having a break for water during a protest. “They might have been these women, had they not been shot dead Dec. 6, 1989,” the annotation explains, thus referencing the misogynist shooting of fourteen women students at École Polytechnique in Montréal. The 1980’s are represented in the women’s clothing, and in fact, Mary Joyce informs me, the painting was created shortly after the unthinkable massacre.

The span of events and rallies is far reaching: “Edmonton welcoming refugees” (oil on canvas 16×16″) in response to Trump’s “caged refugees,” “Canada 150 at the Peace Tower” (oil on canvas 16×16″), depicted in an interesting — and ironic — painting showing the imaginary slow-motion fall of the Peace Tower with a group of young people posing with a banner “Our home on native land” in front of a luminescent old structure of a building, evoking a theatrical scene.

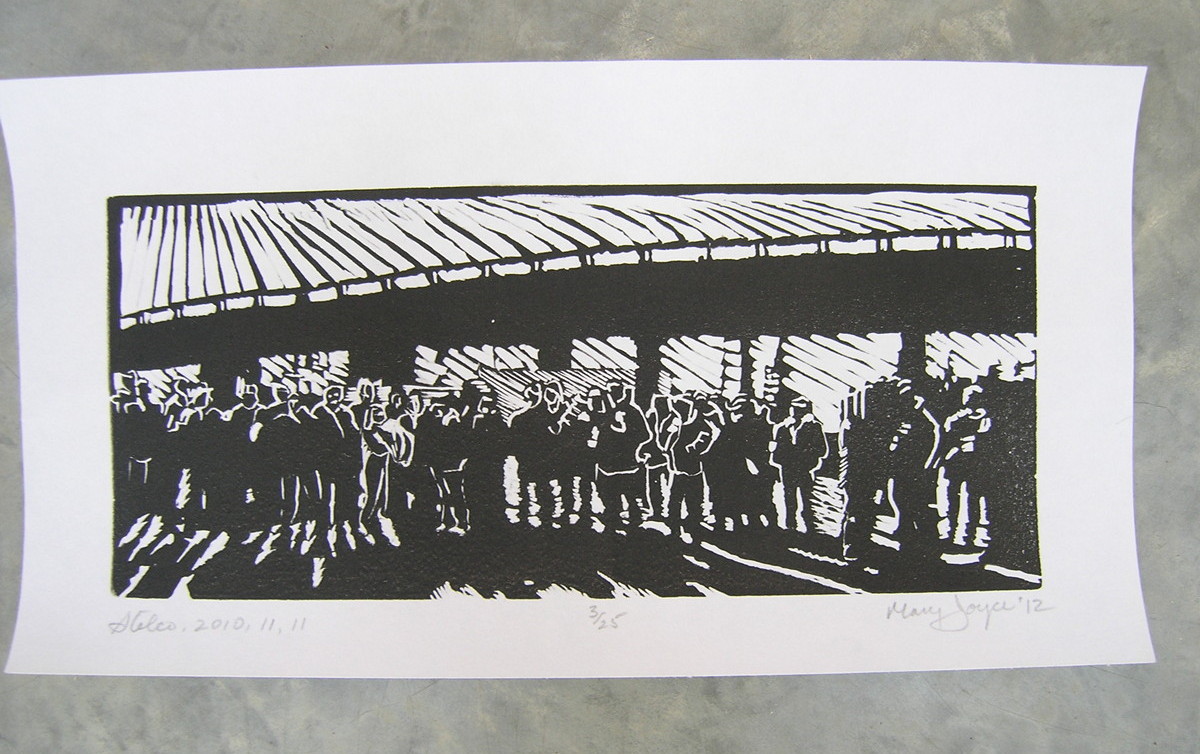

Other images are of the 2010 lockout at Stelco in Hamilton, rendered in a lovely small woodcut, and the “Paris Red Line” march in December 2015 (oil on canvas 28×22″) in connection with the Paris Accord, the red line alluding to a massive red cloth carried along the Champs-Élysées and fronted by the Climate Guardian Angels, wings and all, as if in a magic-realistic story by Gabriel García Márquez.

In 2019 Mary Joyce acted as an international Elections Observer in El Salvador and created a painting of a more intimate school-like street scene (oil on canvas 36×37″) with bold colours and interesting composition of rectangular shapes juxtaposing the organic forms of the figures. And in case the viewer had lost track of Stephen Harper’s anti-terrorism Bill C-51 that became law on June 18, 2015, there is a painting/photo collage to remind them: “Priceless Inestimable” (oil on wood panel with photo collage, 24×24″). Here a photographic image of an Edmontonian participant demonstrating against the bill is prominent while other faces are subtly etched in the red paint along with subtle imprints of safety pins in an abstracted environment.

Abstractions play in fact a frequent role in this exhibition that is dedicated to social causes and political feet on the ground. Cases in point are the 20-inch square paintings that represent abstraction of masses — “Red Square on Earth Day” and “Sherbrooke: 10,000 Carrying a Red Square” — where dots, dashes, opaque and transparent hues in addition to pronounced geometry produce a sense of motion. When asked about the merit of non-representational imagery, the artist explained that abstractions offer the viewer a space to consider their own ideas, associations and interpretations. Moreover, the viewer’s attention will naturally be drawn to the formal features of the work, the application of the paint, the hues, the shapes, the compositions, the aesthetic aspects. This is particularly the case in “Vestige: A nod to Minimalism” (oil on canvas 24×18″), a formalist painting that is both a wink and a nod. On a brilliant scarlet/cadmium red background, a small square appears; its hue is darker, somewhat veiled with a pattern that is recognizable from the crowd abstractions. But the joke lies in the markings above the square in a nearly invisible outline of a square of similar size dotted with bits of shiny, hardened paint, as if the darker square had once sat in its place but later slipped out and slid down to free itself from its original fixed formalist composition. It’s a brilliant minimalist work that along with the large-scale cloth embodies the poetic AND political possibilities suggested by the simple “carré rouge.”

(The exhibition runs until October 22 at La Cité Francophone, 8627-Marie-Anne Gaboury (91) Street, Edmonton.)