|

SUPPLEMENT

No. 24July 4, 2020

Anniversary of Canada's Constitution of

1867

A Modern Demand for Equality

- Hardial Bains -

• The

"New Found Land" and Heroic Resistance

of the Mi'kmaq and Beothuk

- Tony Seed -

For Your Information

• Why Canada Was Called a

"Dominion"

• Letters Patent

Issued to John Cabot

and the Royal Prerogative

Anniversary of Canada's

Constitution of 1867

- Hardial Bains -

Excerpt from A Future to Face written

during the Referendum on the Charlottetown

Accord in 1992.

The demand for a

right is the expression of the extent to which the

human personality has developed in relation to the

conditions of the times. We are talking here about

the human personality as a genre, as the quality

of the times, as the product of social being. The

demand for equality, then, is an historical

product. The modern demand for equality consists

in deducing from that common quality of being

human, from the equality of human beings as human

beings, a claim to equal political and social

status for all human beings, or at least for all

citizens of a state or all members of a society. The demand for a

right is the expression of the extent to which the

human personality has developed in relation to the

conditions of the times. We are talking here about

the human personality as a genre, as the quality

of the times, as the product of social being. The

demand for equality, then, is an historical

product. The modern demand for equality consists

in deducing from that common quality of being

human, from the equality of human beings as human

beings, a claim to equal political and social

status for all human beings, or at least for all

citizens of a state or all members of a society.

The human personality or civilization has evolved

over the millennia, according to the conditions of

the times. There have been times when the

conditions have left their imprint on the

personality and there have been times when that

very personality, in order to remain in step, has

given rise to the demand that the conditions must

change.

In the most ancient and primitive communities,

equality of rights could apply at most to male

members of the community, with women, slaves and

foreigners being excluded from this equality as a

matter of course.

Among Greeks and Romans the inequalities of men

were of much greater importance than their

equality in any respect. Under the Greek Empire

distinctions were made between Greeks and

barbarians, freemen and slaves, citizens and

foreigners. The Romans made the distinction

between Roman citizens and Roman subjects

although, with the exception of the distinction

between freemen and slaves, these distinctions

gradually disappeared. In this way there arose,

for the freemen at least, an equality as between

private individuals on the basis of which Roman

Law, a complete elaboration of law based on

private property, developed.

In the European context during medieval times,

there was the king and the feudal nobility with

their lands and castles while production was

carried out by serfs and indentured labour. All

the rights pertained to the king by divine right

and he ruled in conjunction with the church. In

1215, Magna Carta was signed by which the

barons forced the king to hand some of his rights

over to them.

Under the German domination of medieval Western

Europe, a complicated social and political

hierarchy was gradually built up as had never

existed before and which abolished for centuries

all ideas of equality. In spite of this, in the

course of historical development, a system of

predominantly national states was created for the

first time, exerting mutual influence on each

other and mutually holding each other in check. It

was within these national states that at a later

period the question of equal status of members of

a defined body politic could be raised.

It was finally the epoch of the Renaissance, in

the second half of the 15th century in western

Europe, which brought us to the eve of modern

times. Starting in Italy in the 1400's and

eventually spreading to all of Europe, the new

form of capitalist production was born. Based on

handicraft, on manufacture in the true sense of

the word, it was the starting point for the

large-scale industry of today. Royal power,

founded on the inhabitants of the towns, broke the

feudal power of the nobles and created the great

national monarchies, within which were developed

the new modern states and the new bourgeois

society.

The great geographical and scientific discoveries

of the time assisted this movement. The

discoveries, such as those of Columbus whose

voyage showed that the world is not flat, and

Copernicus who proved that the earth revolves

around the sun, strengthened man's belief in

himself. The invention of the compass opened the

way for daring sea voyages of caravels, the ships

of the 15th and 16th centuries which were fast and

of small tonnage and sailed to and fro across the

oceans, in search of new lands. Only then did

these countries really discover the world for

themselves and the foundations were laid for the

further development of world trade. The invention

of printing in 1450 assisted in the spread of the

texts of Antiquity, and of education and culture.

The discovery of gunpowder, brought by Marco Polo

from China, destroyed the invincibility of the

feudal castles.

These factors brought about an unprecedented

development of the productive forces, but at the

same time they brought a new, more savage,

exploitation of the workers in manufacture and of

the peasants. The social contradictions and the

struggle of the classes were also accentuated. The

inhabitants of the new lands were ruthlessly

pillaged. Popular uprisings shook feudalism.

These changes helped in the birth of the new

world outlook on life and man, expressed in

humanism, and the liberation of man from feudal

and ecclesiastical oppression. The humanists

denounced the hypocrisy of the clerics who taught

man to despise the good things of this world in

order to gain paradise in the life after death.

They insisted that man should attain happiness

through his daily activities and the application

of science. The object of science, philosophy,

literature and the arts now became man himself.

His rights must be defended. He must be brave and

daring, and must judge in an independent manner.

Consequently, he must adopt a critical stance

toward everything which surrounds him. These

qualities are not gained in terms of noble titles,

but by daily activity.

The new culture was not a continuation of the

culture of the Middle Ages, which was a period of

darkness and ignorance, but of that culture which

had been created by the Greco-Roman world. In

every field of creativity of the humanists, one

notes admiration for Antiquity. They believed it

was not possible to create any work of value

without imitating the Ancient which they

considered to be unsurpassable. Engulfed by the

cult of Antiquity, many humanists wrote their

works in Latin, which was incomprehensible to the

ordinary masses. Progressive humanists, however,

fought for national unity and began to write in

national languages.

The whole medieval system of education was

criticized. Religious and scholastic ideology, a

philosophical current of the 11th-14th centuries

which was opposed to science and based itself not

on the analysis of reality but on the dogmas of

the Church, suffered a great blow. The study of

Antiquity gave a new impetus to the experimental

sciences, which began to free themselves from

teleology, the religious doctrine that everything

has a pre-ordained design or aim.

However, it must be kept in mind that all the

advantages of this society pertained to that

strata which could afford leisure time. The masses

of people, highly exploited, were unable to

receive culture and education and were not

recognized as having any rights.

In the economic domain, trade had far surpassed

the importance both of mutual exchange between

various European countries and the internal trade

within each individual country. American silver

and gold flooded Europe. The handicraft industry

could no longer satisfy the rising demand; in the

leading industries of the most advanced countries,

it was replaced by manufacture. The mighty changes

in the conditions of economic life demanded

corresponding changes in the political structures.

Trade on a large scale, international trade and,

more so, world trade, required free owners of

commodities who were unrestricted in their

movements and, as such, enjoyed equal rights. They

needed to be able to exchange their goods on the

basis of laws which were equal for them all, at

least in each particular theatre of operation. The

transition from handicraft to manufacture

presupposed the existence of a number of free

workers, on the one hand from the fetters of the

guilds and, on the other, whereby they could

themselves utilize their labour power and, hence,

as parties to a contract, have equal rights.

This is the context

in which the modern demand for equality takes

shape. The economic relations required freedom and

equality of rights, but the political system

opposed them. It was left to the great men of the

18th century, especially in France, to transcend

the thinking of the preceding age. The work which

is the most representative of this age, the Age of

Enlightenment, was the Encyclopédie,

published between 1750 and 1789 in Paris by Denis

Diderot with the assistance of Jean le Rond

d'Alembert, and which included contributions by

some forty other 'philosophes,' including

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, François Marie Arouet de

Voltaire, the Baron de Montesquieu, François

Quesnay, Fontenelle, the Baron d'Holbach and the

Compte de Buffon, as well as countless anonymous

skilled workers and craftsmen and artisans

consulted by the editors for the details on

mechanical, construction and other technical

instruments. It was also greatly influenced by men

such as the Abbé de Condillac and Claude-Adrien

Helvetius. It became a summation and

crystallisation of the development of human

knowledge up to the time of its publication in the

mid-1700's. Above all, it was an instrument of war

against all the prejudices of the Ancien Régime.

The Encyclopédistes energetically set out to

popularise on an unprecedented scale the results

of the scientific revolution so as to serve as a

force for change in the society itself. It was a

colossal commitment to social change, to

harnessing human knowledge for social reform. It

is clear that the popularisation of the

accomplishments of the scientific revolution

necessarily led to a fundamental and earth shaking

challenge of all the ideas and tenets on which the

society of the Ancien Régime was founded. Robert

Niklaus, in an essay entitled The Age of the

Enlightenment, writes: This is the context

in which the modern demand for equality takes

shape. The economic relations required freedom and

equality of rights, but the political system

opposed them. It was left to the great men of the

18th century, especially in France, to transcend

the thinking of the preceding age. The work which

is the most representative of this age, the Age of

Enlightenment, was the Encyclopédie,

published between 1750 and 1789 in Paris by Denis

Diderot with the assistance of Jean le Rond

d'Alembert, and which included contributions by

some forty other 'philosophes,' including

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, François Marie Arouet de

Voltaire, the Baron de Montesquieu, François

Quesnay, Fontenelle, the Baron d'Holbach and the

Compte de Buffon, as well as countless anonymous

skilled workers and craftsmen and artisans

consulted by the editors for the details on

mechanical, construction and other technical

instruments. It was also greatly influenced by men

such as the Abbé de Condillac and Claude-Adrien

Helvetius. It became a summation and

crystallisation of the development of human

knowledge up to the time of its publication in the

mid-1700's. Above all, it was an instrument of war

against all the prejudices of the Ancien Régime.

The Encyclopédistes energetically set out to

popularise on an unprecedented scale the results

of the scientific revolution so as to serve as a

force for change in the society itself. It was a

colossal commitment to social change, to

harnessing human knowledge for social reform. It

is clear that the popularisation of the

accomplishments of the scientific revolution

necessarily led to a fundamental and earth shaking

challenge of all the ideas and tenets on which the

society of the Ancien Régime was founded. Robert

Niklaus, in an essay entitled The Age of the

Enlightenment, writes:

Thirst for knowledge

and intellectual curiosity were directed to the

external world. Awareness of the history,

languages and religions of people from foreign

countries; the new developments in science,

especially physics, mathematics and the natural

sciences and medicine, were changing the climate

of opinion throughout the civilized world.

Attention was drawn to the ethics, politics and

economics of social man, but it centred on

individual man, his nature, his happiness, his

relationship to the cosmos, the very processes of

his mind and their validity...

Frederick Engels, in his book Anti-Dühring

points out:

The great men who in

France were clearing the minds of men for the

coming revolution... recognized no external

authority of any kind. Religion, conceptions of

nature, society, political systems, everything was

subjected to the most merciless criticism;

everything had to justify its existence. The

reasoning intellect was applied to everything as

the sole measure. It was the time when...the world

was stood upon its head; first, in the sense that

the human head and the principles arrived by its

thought claimed to be the basis of all human

action and association; and then later on also in

the wider sense, that the reality which was in

contradiction with these principles was in fact

turned upside down from top to bottom. All

previous forms of society and government, all the

old ideas handed down by traditions, were flung

into the lumber-room as irrational; the world had

hitherto allowed itself to be guided solely by

prejudices; everything in the past deserved only

pity and contempt. Now for the first time appeared

the light of day; henceforth, superstition,

injustice, privilege and oppression were to be

superseded by eternal truth, eternal justice,

equality grounded in Nature and in the inalienable

rights of man.

This vindication of the rights of man and of the

need to establish a better world on earth heralded

the beginning of modern times. In his book Les

philosophes, Norman L. Torrey points out

that our ideas of what constitutes the basic

principles of democracy thus emerge from the

writings of the "philosophes."

He writes:

The sense of equity,

the feeling that there ought to be a law,

antecedent to every positive and written law...was

explained by d'Alembert as being acquired through

experience with injustice, a theory of which

Voltaire's overriding passion for justice was a

notable example.

John Morley in his work Diderot and the

Encyclopaedists points out that:

In saying...that the Encyclopedists began a

political work, what is meant is that they drew

into the light of new ideas, groups of

institutions, usages and arrangements which

affected the real well-being and happiness of

France, as closely as nutrition affected the

health and strength of an individual Frenchman.

It was the Encyclopedists who first stirred

opinion in France against the iniquities of

colonial tyranny and the abominations of the

slave trade. They demonstrated the folly and

wastefulness and cruelty of a fiscal system that

was eating the life out of the land. [...] It

was this band of writers...who first grasped the

great principle of modern society, the honour

that is owed to productive industry. [...]

aroused the attention of the general public to

the causes of the forced deterioration of French

agriculture, namely the restrictions on trade in

grain, the arbitrariness of the imposts, and the

flight of the population to the large towns.

[...] When it is said, then, that the

Encyclopedists deliberately prepared the way for

a political revolution let us remember that what

they really did was to shed the light of

rational discussion on ...practical grievances.

But at the same time,

...not one of the 'philosophes' was truly a

democrat. In their writings are found the

intellectual origins of the French Revolution,

but they were not revolutionaries. Montesquieu

included in his Spirit of Laws a

history of the origins and a defence of the

feudal privileges which he shared as a member of

the nobility. One aspect of his theory of the

balance of powers was a House of Lords to serve

as a stabilising force between the King and the

lower house. Voltaire, as a benevolent landlord,

mistrusted the people, who were ever prey to

superstition and fanaticism, and believed that a

constitutional monarchy was the best solution

for France. Rousseau shared Plato's mistrust of

democracies and the almost universal belief that

democratic administration procedures were

impossible in large nations. Government by

representation, they felt, could only lead to

usurpation and corruption. Faced with this

dilemma, Montesquieu suggested a federated

republic, or society of societies, through which

democratic institutions might be saved and the

defensive strength of its members maintained.

In summing up the political contribution of the

Encyclopédistes, Robert Niklaus writes:

It is agreed that for a long time the

"philosophes" pinned their hopes of reform on an

ideal Legislator, who would ensure happiness and

virtue, than on an enlightened despot, and only

reluctantly, at a late stage and out of despair,

turning away from the monarchy to espouse

Republican ideals that were often inspired by

Rousseau, whom few really understood at the

time. For the most part they were more concerned

with practical reforms, affecting commerce and

industry; and civil reforms, by which men would

be allowed to do all that the laws were prepared

to sanction. They did not ask for political

freedom, as is clear from a perusal of the

article Liberté in the Encyclopédie.

They did not wish to see all forms of censorship

abolished, but rather the appointment of censors

favourable to their cause. They unfailingly

attacked inequalities in the social system, and

the idea of a social contract as the basis of

society gained ground, with its implication that

if the ruler breaks the tacit contract between

himself and his subject, he may be removed.[1]

Rousseau's idea of the need for popular consent

provided a rational basis for the revolution which

was to follow against the conception of rights

captured in the declaration of Louis XIV, "L'État,

c'est moi." Rousseau's declaration that "All men

are born equal" was used to explain how natural

man may be denaturalized and remoulded into civil

man, how civil liberty may be substituted for

natural liberty and how equality may be regained

through a society founded on the general will of a

sovereign people. The Social Contract was put

forward as the logical basis of all legitimate

authority. The general principles of the social

contract include the idea that no man has any

natural authority over his fellow man and thus no

king rules by divine right. The individual as the

basic unit surrenders his natural right to the

state, in which he is both sovereign and subject.

He advances the concept of civil rights which

supplant the natural forces and that might does

not make right. Might he says always remains a

supreme court of appeal and justifies revolution

against tyranny or the usurpation of political

powers.

Rousseau poses the problem as follows:

I suppose men to have reached the point at

which the obstacles in the way of their

preservation in the state of nature show their

power of resistance to be greater than the

resources at the disposal of each individual for

his maintenance in that state. That primitive

condition can then subsist no longer; and the

human race would perish unless it changed its

manner of existence.

But as men cannot engender new forces, but only

unite and direct existing ones they have no

other means of preserving themselves than the

formation, by aggregation, of the sum of forces

great enough to overcome the resistance. These

they have to bring into play by means of a

single motive power, and cause to act in

concert.

This sum of forces can arise only where several

persons come together: but, as the force and

liberty of each man are the chief instruments of

his self-preservation, how can he pledge them

without harming his own interests, and

neglecting the care he owes to himself?

He states this difficulty as follows:

The problem is to find a form of association

which will defend and protect with the whole

common force the person and goods of each

associate, and in which each, while uniting

himself with all, may still obey himself alone,

and remain as free as before. This is the

fundamental problem of which the Social

Contract provides the solution.

The clauses of the Social Contract, he

writes, may be reduced to one:

the total alienation of each associate,

together with all his rights, to the whole

community; for, in the first place, as each

gives himself absolutely, the conditions are the

same for all; and, this being so, no one has any

interest in making them burdensome to others.

He writes:

...each man, in giving himself to all, gives

himself to nobody; and as there is no associate

over which he does not acquire the same right as

he yields others over himself, he gains an

equivalent for everything he loses, and an

increase of force for the preservation of what

he has.

At once, in place of the individual personality

of each contracting party, this act of

association creates a moral and collective body,

composed of as many members as the assembly

contains voters, and receiving from this act its

unity, its common identity, its life, and its

will. This public person, so formed by the union

of all other persons, formerly took the name of

city, and now takes that of Republic or body

politic; it is called by its members State when

passive, Sovereign when active, and Power when

compared with others like itself. Those who are

associated in it take collectively the name of

people, and severally are called citizens, as

sharing in the sovereign power, and subjects, as

being under the laws of the State. But these

terms are often confused and taken one for

another: it is enough to know how to distinguish

them when they are being used with precision.

Rousseau's concept of sovereignty then is

"nothing less than the exercise of the general

will" which alone "can direct the State according

to the object for which it was instituted, i.e.

the common good: for if the clashing of particular

interests made the establishment of societies

necessary, the agreement of these very interests

made it possible. The common element in these

different interests is what forms the social tie;

and, were there no point of agreement between them

all, no society could exist. It is solely on the

basis of this common interest that every society

should be governed."

The sovereign power, he says, can be transmitted,

but not the will.

Such a conception aroused people in Europe and

the Americas and made them conscious of their

rights within these conditions. The rising

industrialists and merchants although continually

growing richer, were deprived of political rights.

The highest state posts were in the high ranks of

the nobility who guarded their power jealously,

mercilessly suppressing every organized movement.

The maintenance of the royal court swallowed up

huge sums of money. The taxation policy was so

savage that it not only produced a series of

peasant uprisings but also seething rebellion in

many of the colonies.

The French Revolution struck a heavy blow at the

bases of the old feudal order and a new class, the

bourgeoisie, came to power and took over the

positions of authority. The American War of

Independence took place creating the United States

of America. Since these great achievements of the

18th century, a period of two centuries ensue

filled with the turmoil of growth and development,

reflected in all spheres.

Conclusion

Since at least the beginning of the twentieth

century the issue of the discredited party system

and political process has been coming to the fore

time and again. The electorate seeks to have a

role in the decisions which governments make.

Repeated national crises have served to eclipse

this problem to the extent that during such crises

governments put themselves forward as

representatives of the will of the nation. This

was the case during the first and second world

wars. The most recent example of such a thing was

the way American public opinion rallied behind

George Bush during the American attack in the Gulf

War and then, once the perceived national crisis

was over, demanded he do something about the state

of the American economy.

It is no accident that this notion of "national

will" gets mixed up with "popular will"; one has

to do with the issue of the nation as a whole and

the other is related to the relations between the

citizens and their body politic. One cannot

replace the other.

What we have to deal with is the flaw

which exists in the democratic system and in the

political process, because both of them do not

represent the modern constituency. During the 18th

and 19th centuries, they were consistent with

their constituency which were the propertied

classes which had risen to assert their claim to

political power. This takes place whether in the

colonial heartlands, or in the colonies. What we have to deal with is the flaw

which exists in the democratic system and in the

political process, because both of them do not

represent the modern constituency. During the 18th

and 19th centuries, they were consistent with

their constituency which were the propertied

classes which had risen to assert their claim to

political power. This takes place whether in the

colonial heartlands, or in the colonies.

In the course of the development of the last two

centuries, the political franchise becomes

universal; not only are women included, but also

those Imperial England had considered "inferior

races." In Canada, it is when the Native people

finally get the franchise that the suffrage is

made truly universal. It would seem that once the

franchise becomes universal, the discrepancy

between where the political power lies and who has

political rights grows. This flaw in the democracy

is never addressed.

When the new political power came into being in

the 18th and 19th centuries, it represented a

definite constituency. All notions of

representative government, popular government and

responsible government were generally speaking "in

sync" with the propertied classes which formed the

political constituency. When there was no

contradiction manifested between the legal

sovereignty and the political sovereignty, a more

or less harmonious situation existed. Once the

political parties in the Parliament no longer

represent the various constituencies among the

electors, the contradiction flares up, with the

discontent of the people becoming paramount and

the powers that be seeking a national crisis in

order to overcome the problem. But this only

diverts from the real issues of the need to renew

the democracy; the political system which has a

contradiction between the constituency which has

power and the constituency which is empowered in

name. On the other hand lies the need to renew

Canada; the need to incorporate all the Canadian

people into the Canadian nation. The issue is to

give human rights a definition and a political

guarantee as well as to give national rights a

political guarantee. Such a thing is required to

renew the democracies everywhere.

Today, after the Cold War period is over, it is

not the first time the issue has arisen that the

democracies need renewal. The flaw that the

political power no longer politically represents

the entire constituency which now includes all

human beings, not just those with property, has to

be addressed. How to empower the constituency as

it exists today is the fundamental problem at

hand.

The issue of renewing Canada is slightly

different. This concerns the nation and is linked

with the issue of the federation, how it was

formed and with what exists today. When Canada was

made a federation, the British North America

Act declared that in all matters not

pertaining to the distribution of powers, the

rulings of the Parliament of England would apply.

In other words, in all matters pertaining to the

relationship between the citizenry and their

government, Canada inherited the entire corpus of

English constitutional and non-constitutional law,

all Acts of the British Parliament from the time

of the Norman Conquest. Until 1949, the highest

Canadian Court was the Judicial Committee of the

Privy Council which sat in London and was composed

largely of English judges. English common law

developments were incorporated, more or less,

automatically into Canadian common law. Since

1949, English decisions have not been binding but

treated with great respect by the Supreme Court of

Canada. Since 1982, no act of the British

parliament can extend to Canada as part of its

law.

When we talk of

Canada coming of age, the first step came in 1867

when it got self-government; the second step came

in 1949, when Canadians were no longer bound by

the decisions of the English Parliament and

English courts. The third step came in 1982 when

the constitution was patriated and the British

Parliament no longer held the right to amend the

Canadian constitution and veto the decisions of

the Canadian legislatures.... When we talk of

Canada coming of age, the first step came in 1867

when it got self-government; the second step came

in 1949, when Canadians were no longer bound by

the decisions of the English Parliament and

English courts. The third step came in 1982 when

the constitution was patriated and the British

Parliament no longer held the right to amend the

Canadian constitution and veto the decisions of

the Canadian legislatures....

The political crisis, the crisis caused by the

fact that the legal sovereignty and the political

sovereignty are out of step with each other can

also not be sorted out without resolving the

Constitutional crisis, without recognizing the

need to draft a new constitution which gives

Canadians 1. a renewal of their federation and 2.

a political constitution which is theirs, not one

which can merely be understood by those who come

out of the English tradition. This is not a matter

of throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Canadians would wish to enshrine in their

constitution the most advanced experience human

civilization has given rise to. The issue is not

to have the most perfect constitution; the issue

is to learn from our experience with democracy and

learn from that of others since the 18th century

and make our own further contribution to this

experience.

Note

1. The Age of the Enlightenment, by

Robert Niklaus

- Tony Seed -

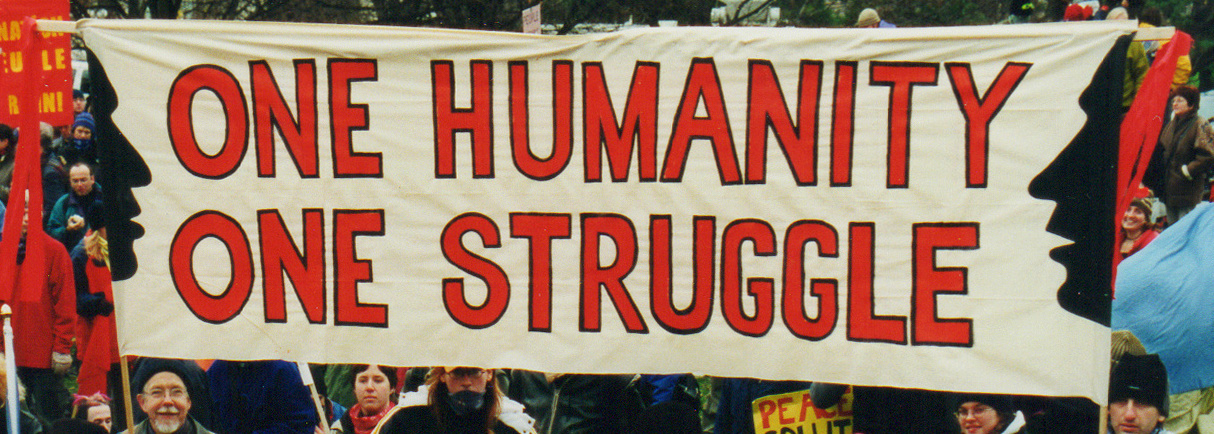

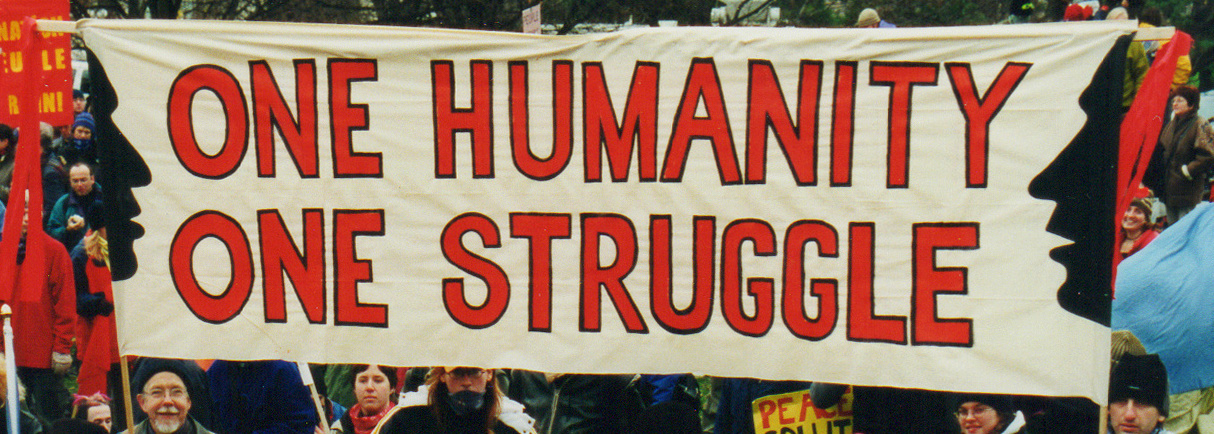

Mi'kmaq resistance carries on to the present.

Above, they militantly defend their hereditary

rights blocking a fracking operation near Rexton,

New Brunswick, October 7, 2013.

The Venetian navigator Giovanni Caboto (John

Cabot), commissioned by Henry VII of England,

landed in Newfoundland on June 24, 1497. Believing

it to be an island off the coast of Asia, he named

it New Found Land.[1]

Under the commission of this king to "subdue,

occupy, and possesse" the lands of "heathens and

infidels," Caboto reconnoitred the Newfoundland

coast and also landed on the northern shore of

Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia.[2]

He returned to England on August 6, 1497 and took

three Mi'kmaq with him thereby introducing the

enslavement of human persons into North America.

This may be responsible for his disappearance when

he returned to Newfoundland with five ships in

1498. When his ships arrived in northern Cape

Breton Island, the Mi'kmaq attacked. Only one ship

arrived back in England, the other four, including

the one with Caboto as captain, never returned.

Caboto's own family was enriched by the slave

trade. His son Sebastian, while working for the

Spanish king in 1529, apparently purchased "50 to

60 slaves ... in Brazil, for ... sale in Seville."[3]

The royal charter stipulated that King Henry VII

would acquire "rule, title, and jurisdiction" over

all lands "discovered" by Cabot. It is the

foundation upon which the "Dominion of Canada," as

a supposed legal entity, is based.[4] Caboto, sailing

from Bristol, a strategic port in the Atlantic

slave trade, represented the trading, commercial

and shipping houses -- such as Lloyds of London

and Barclays Bank -- who amassed fabulous wealth

from the kidnapping of Africans and later financed

the neo-colonial confederation of Canada, created

in 1867, and its railroads from their booty.

Caboto had told stories of the sea teeming with

fish on his return to England. European colonial

fishing fleets began making trips to the Grand

Banks every summer.

Initially the Mi'kmaq and Beothuk, however

reluctantly at times, treated the visitors as

political equals in most important respects and

were willing to trade and allow the Europeans to

briefly land and dry the cod. In 1500, Gaspar

Corte-Real, a slave trader financed by Portugal,

captured several Mi'kmaq. He trolled the coast of

Newfoundland and Labrador with three ships,

kidnapping 57 "man slaves" (Beothuks) to be sold

to finance the cost of the expedition, and

claiming it on behalf of Portugal. His belief that

Nitassinan was teeming with potential captives led

to it being called Labrador, "the source of labour

material." While two of the ships returned to

Portugal, Corte-Real and his ship were lost at

sea.

By 1504 Bretons were fishing off the coast of

Mi'kma'ki country. The fishermen dried their catch

on shore and began trading fur with the Mi'kmaq,

giving rise to a new commodity and European dreams

of greater riches. In 1507 Norman fishermen took

another seven Beothuk prisoners to France. This

affected all future relations between the Beothuk,

Mi'kmaq and the fishermen.

João Álvares Fagundes (1521-25), Giovanni da

Verrazano (1524), and Estebán Gomez (1525)

followed to Mi'kma'ki.

The French "Discovery" of Kanata

The French explorer Jacques Cartier dropped

anchor in Baie des Chaleurs, New Brunswick in

1534. Alarmed by the hundreds of Mi'kmaq in canoes

waving beaver skins, he fired cannon over their

heads. The Mi'kmaq, who were willing to trade, had

to retreat. Cartier began trading with them after

being reassured that this was not a hostile

attack. He then sent Indigenous prisoners to

France. He subsequently landed July 24, 1534 at

Baie de Gaspé on territory inhabited by the

Haudenosaunee. The French erected a large cross

and Cartier claimed possession of the land in the

name of the French king François I. When

confronted by the Haudenosaunee, Cartier said the

cross was merely a navigational marker. Later,

Cartier was guided to the village (Kanata) of

Stadacona (present day Quebec City) by two

Haudenosaunee youths. He designated the entire

region north of the St. Lawrence River as "Canada"

-- a colonizer's designation that came to

encompass a massive swath of Turtle Island, where

a nation state was later born on hundreds of

nations already existing across the breadth of

what is now called Canada.[5]

An epidemic of an unknown illness struck the

Maritimes in 1564-70, decimating the Mi'kmaq

population.

The Gilbert Patent of "Discovery"-- Newfoundland

On July 11, 1578, Sir Humphrey Gylberte (Sir

Humphrey Gilbert) received a grant from Queen

Elizabeth I to discover and occupy in the next six

years a site for a colony not already in European

hands.[6]

While he himself could hold land there and convey

it to others, all would in turn be held by the

Crown and his colony was to be governed by laws

agreeable to those of England. He, along with his

half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh, was already a

colonizer through English colonial plantations in

Gaelic Ireland (Ulster and Munster). In 1583,

after an earlier failed attempt, Gilbert followed

in the well-known track of the fishing fleet to

the Grand Banks, where he attempted to settle a

colony in Newfoundland.

Gilbert failed to withstand the cold and

starvation due to the lack of resources, but he

nonetheless laid formal claim to Newfoundland and

the Maritimes on August 5, 1583. France, citing

Jacques Cartier's voyage and the doctrine of

"discovery," opposed the claim. Gilbert lost one

ship off Sable Island on August 29,1583 -- recorded as

Canada's first "marine disaster," -- and subsequently

drowned in a storm on September 9, 1583 near the Azores.

In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh had Gilbert's patent

reissued in his favour, with Newfoundland excluded

from its scope, and he made a series of

unsuccessful attempts to establish plantation

colonies on Roanoke Island. Although the island

was located off the coast of North Carolina, he

named it as part of the land called Virginia, in

honour of Queen Elizabeth I of England, who was

referred to as the Virgin Queen.

In 1586, typhus was spread amongst the already

weakened Mi'kmaq population, and yet more lives

were lost to a deadly disease brought by the

Europeans.

Every monarch and their

family from Elizabeth Tudor onwards were

financiers and beneficiaries of this trade in

human flesh. By the 18th century, having

overcome the Dutch, Spanish and French colonial

empires, Britain ruled the seas with a system of

overseas naval-military bases such as Halifax,

and emerged as the world's leading human

trafficker and had a virtual monopoly over the

cod trade. About half of all enslaved Africans

were transported in British ships. Eighty per

cent of Britain's income was connected with

these activities.

A century and a half later, in 1756 on order of King

George II, Governor Lawrence of Nova Scotia expelled as many as 10,000

Acadians in the Great Upheaval (Le Grand Dérangement) for

refusing to take an oath of loyalty to Britain. In parallel, unable to

stop the Mi'kmaq resistance, bounties were paid for scalps of both

Mi'kmaq and Acadians. Many Acadians fled into the forests and fought a

guerilla war beside the Mi'kmaq, carrying out a series of military

operations against the British. (Many others died at sea or settled

here and there. Many became the modern day Cajuns in Louisiana.)

By 1758 over 400 fishing boats were gathering

every summer off Newfoundland and the Maritimes.

The development of the Atlantic fisheries, a

seemingly inexhaustible source of cheap protein,

is inextricably linked to the Atlantic slave

trade, which fertilized the development of the

capitalist system and the consolidation of

national states in Europe. It later formed the

basis of the wealth of leading families in

colonial Nova Scotia and New England.

By this time, millions of Indigenous peoples had

been slaughtered in South America and the

Caribbean.

The 500th Anniversary of Caboto's Landfall

In 1997, on the quincentennial of Caboto's landfall, the sovereign of Canada, Queen Elizabeth II,

toured the country sponsored by the Canadian and

British governments. According to her, Caboto's

landfall "represented the geographical and

intellectual beginning of modern North America "

-- the Eurocentric Discovery Doctrine.[7] As is well

known, Newfoundland is where the genocide of the Beothuk

Indians occurred. Queen Elizabeth was right -- the

pattern was set there. So far as the Indigenous

peoples are concerned, of course, the pattern set

was genocide. The Beothuk were exterminated by the

1830s. By 1867, the population of the Mi'kmak had

been reduced to some 2,000. The Inuit dropped from

approximately 500,000 before contact to some

102,000 by 1871.

When Queen Elizabeth II visited Sheshatshiu in

Labrador, the reception was "mixed," as

"protestors waved placards denouncing her visit."[8]

Innu women demonstrate in the mid-1980s

against NATO overflights and for

self-determination for their homeland

which they call Nitassinan.

|

The Canadian Press reported: "Aboriginals have

said it's insulting to celebrate explorer John

Cabot's arrival in North America because of the

devastating impact colonization has had on them.

The Queen's visit to this riverside community

(Bonavista) of 1,200 stood out on other levels.

Dogs meandered about her sand-covered route and

there was not a Union Jack or Maple Leaf in sight.

There was none of the gushing witnessed at

previous events this week ..."[9]

In Sheshatshiu, Innu community leaders presented

her a letter on June 26, 1997 that read in part:

"The history of colonization here has been

lamentable and has severely demoralized our

People. They turn now to drink and

self-destruction. We have the highest rate of

suicide in North America. Children as young as 12

have taken their own life recently. We feel

powerless to prevent the massive mining projects

now planned and many of us are driven into

discussing mere financial compensation, even

though we know that the mines and hydroelectric

dams will destroy our land and our culture and

that money will not save us.

"The Labrador part of Nitassinan was claimed as

British soil until very recently (1949), when

without consulting us, your government ceded it to

Canada. We have never, however, signed any treaty

with either Great Britain or Canada. Nor have we

ever given up our right to self-determination.

"The fact that we have become financially

dependent on the state which violates our rights

is a reflection of our desperate circumstances. It

does not mean that we acquiesce in those

violations.

"We have been treated as non-People, with no more

rights than the caribou on which we depend and

which are now themselves being threatened by NATO

war exercises and other so-called development. In

spite of this, we remain a People in the fullest

sense of the word. We have not given up, and we

are now looking to rebuild our pride and self

esteem."[10]

On June 30, 2004 the late Keptin Saqamow Reginald

Maloney opened the Halifax International Symposium

on the Media and Disinformation held at Dalhousie

University by delivering the fraternal welcome of

his people to the participants from North America,

Europe and Asia. "The greatest disinformation we

have faced is that of the 'discovery doctrine' of

the Spanish, Portuguese and British colonial

powers, which still ravages us today," he declared

in his welcoming address.[11]

On October 12, 2013 the Mi'kmaq Warriors Society

and Elsipogtog First Nation in New Brunswick, who

were blockading a Texas monopoly's fracking

operation demanded, as was their right, that the

government "produce documents proving Cabot's

Doctrine of Discovery."

The important question is not the Queen, but why

the political power does not represent all human

beings. The resistance of the First Nations and

different collectives of the Canadian people to

the new arrangements of the mid-19th century

creating the Confederation of Canada, in defence

of their rights, is outstanding and

second-to-none. The just demands of the Indigenous

peoples for the recognition of their rights is not

a matter of a "special interest" but an issue

facing the entire polity, which can only be

resolved through modern arrangements that uphold

rights on the basis that they are inviolable and

belong to people by virtue of their being.

Notes

1. The main source for this

article is "Mi'kmaq & First Nations Timeline

(75,000 BC -- 2000 AD): Eclipse &

Enlightenment," Tony Seed and the editors of Shunpiking

Magazine, Halifax, 2000. With a file from

Richard Sanders.

Contrary to all traditional European accounts of

the "discovery" of America, which put the Vikings

in first place followed by Columbus, overwhelming

anthropological evidence places Africans in the

Americas since the 9th century. Long before

Europeans arrived on the shores of the Americas,

evidence indicates that Africans have already

travelled to the Americas, including Quebec, and

that the Mi'kmaq from the Maritimes had reached

Europe and Africa.

In one account predating the official "discovery"

of America, in 1398, Prince Henry Sinclair, a

Scotsman, reputedly landed in Cape Caruso,

Guysborough, travelled to Pictou and Stellarton,

stayed with the Mí'kmaq for a year, built a ship

and sailed back home. The story is disputed but,

according to Kerry Prosper of Afton, Mi'kmaq

motifs from that time are clearly evident today at

the Sinclair estate in Scotland, which he has

visited. [Personal communication]

The following excerpt from "Looking Forward,

Looking Back," the first volume of the Report

of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples,

published in October 1996 reflects the traditional

European account of discovery:

"First contacts between Aboriginal peoples and

Europeans were sporadic and apparently occurred

about a thousand years ago when Norsemen

proceeding from Iceland and Greenland are believed

to have voyaged to the coast of North America.

There is archaeological evidence of a settlement

having been established at L'Anse aux Meadows on

the northern peninsula of what is now

Newfoundland. Accounts of these early voyages and

of visits to the coast of Labrador are found in

many of the Norse sagas. They mention contact with

the indigenous inhabitants who, on the island of

Newfoundland, were likely to have been the Beothuk

people, and on the Labrador coast, the Innu.

"These early Norse voyages are believed to have

continued until the 1340s, and to have included

visits to Arctic areas such as Ellesmere and

Baffin Island where the Norse would have

encountered Inuit. Inuit legends appear to support

Norse sagas on this score. The people who

established the L'Anse aux Meadows settlement were

agriculturalists, although their initial economic

base is thought to have centred on the export of

wood to Greenland as well as trade in furs.

Conflict with Aboriginal people likely occurred

relatively soon after the colony was established.

Thus, within a few years of their arrival, the

Norse appear to have abandoned the settlement and

with it the first European colonial experiment in

North America.

"Further intermittent commercial contacts ensued

with other Europeans, as sailors of Basque,

English, French and other nationalities came in

search of natural resources such as timber, fish,

furs, whale, walrus and polar bear."

2. Caboto came armed with

assumptions similar to those of the Spanish

colonialists further south. Thus, the letters

patent issued to John Cabot by King Henry VII gave

the explorer instructions to seize the lands and

population centres of the territories "newely

founde" in order to prevent other, competing

European nations from doing the same:

"And that the aforesaid Iohn and his sonnes...may

subdue, occupie, and possesse, all such townes,

cities, castles, and yles, of them founde, which

they can subdue, occupie and possesse, as our

vassailes and lieutenantes, getting vnto vs the

rule, title, and iurisdiction of the same

villages, townes, castles and firme lands so

founde.... "

Historian Hans Koning points out:

"From the beginning, the Spaniards saw the Native

Americans as natural slaves, beasts of burden,

part of the loot. When working them to death was

more economical than treating them somewhat

humanely, they worked them to death.

"The English, on the other hand, had no use for

the Native peoples. They saw them as devil

worshippers, savages who were beyond salvation by

the church, and exterminating them increasingly

became accepted policy."

From The Conquest of America: How the

Indian Nations Lost Their Continent (New

York: Monthly Review Press, 1993), p. 46.

3. Cited by J.A.

Williamson in The Cabot Voyages and Bristol

Discovery Under Henry VII (1962).

4. While the King gave

Cabot the "full and free authority, faculty and

power" to "find, discover and investigate

whatsoever islands, countries, regions or

provinces of heathens and infidels," there was an

important caveat, as Richard Sanders points out.

Cabot's licence only applied to lands that "were

unknown to all Christians." With this imperial

licence to wage an unending, plunderous war

against non-Christians, Cabot and "his sons or

their heirs and deputies" gained the exclusive

right to rule as the King's "vassals and

governors, lieutenants and deputies." In exchange,

they were "bounden and under obligation" to pay

King Henry "either in goods or money, the fifth

part [20 per cent] of the whole capital gained."

The "capital" was defined as "all the fruits,

profits, emoluments [earnings], commodities, gains

and revenues."

"John

Cabot and Britain's Fictitious Claim on Canada:

Finding our National Origins in a Royal Licence

to Conquer," by Richard Sanders, Press for

Conversion!, Magazine of the Coalition to

Oppose the Arms Trade, No. 69. (PDF)

5. Hoping Against Hope?

The Struggle Against Colonialism in Canada.

A three-part audio documentary series, Praxis

Media Productions and the Nova Scotia Public

Interest Research Group, 2007. Audio files for the

series are available here.

6. "[Gilbert's] vision of a

transplanted English gentry exploiting vast new

American lands in a feudal setting was not wholly

unrealistic (it was to be realized later, to some

extent, in Maryland) but his plans were far too

wide-ranging for his resources and there was some

lack of scruple in his easy disposal in bulk of

lands which he had never seen."

"Gilbert, Sir Humphrey," David B. Quinn in Dictionary

of Canadian Biography, Vol. 1, University of

Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, accessed June

28, 2020.

7. The Eurocentric outlook

was developed with the rise of the slave trade.

Eurocentrism is a specific manifestation of

ethnocentrism, which is:

"(1) the belief in the inherent superiority of

one's own group and culture accompanied by a

feeling of contempt for other groups and cultures;

(2) a tendency to view alien groups or cultures in

terms of one's own."

The Eurocentric worldview looks down on all

persons of African or other descent as subhuman,

peoples without history or thought, destined for

servitude. Before the European slave trade

emerged, no uniform or universal racist ideology

existed.

8. Vancouver Province,

June 25, 1997.

9. "Labrador

protest: Royal visitors get mixed reception,"

by Michelle McAfee -- Canadian Press, Victoria

Times-Colonist, Friday, June 27,

1997, p. A10.

10. Letter

from Innu People to Queen Elizabeth II

11. "In

Memoriam -- Reginald Maloney: A Reflection by

Tony Seed," December 6, 2013.

For Your

Information

The following explanation of the word Dominion as

used in the name given Canada when it was

constituted in 1867 was given by Tonya Gonnella

Frichner. Tonya was a professor from upstate New

York as well as a lawyer and highly respected

activist whose academic and professional life was

devoted to the pursuit of human rights for

Indigenous peoples. This excerpt is from "Impact

on Indigenous Peoples of the International Legal

construct known as the Doctrine of Discovery,

which has served as the Foundation of the

Violation of their Human Rights," UN Permanent

Forum on Indigenous Issues, February 4, 2010. She explained:

The Old World idea of property was well

expressed by the Latin word dominium:

from dominus, ... and the Sanskrit domanus

(he who subdues). Dominus carries the

same principal meaning (one who has subdued), extending naturally to signify "master,

possessor, lord, proprietor, owner."

Dominium takes from dominus the sense of "absolute ownership" with a special legal

meaning of "property right of ownership" (Lewis

and Short, A Latin Dictionary, 1969).

Dominatio extends the word into "rule,

dominium, and ... with an odious secondary

meaning, unrestricted power, absolute dominium,

lordship, tyranny, despotism. Political power

grown from property -- dominium -- was, in

effect, domination." (William Brandon, New

Worlds for Old, 1986, p.121).

State claims and assertions of "dominion" and "sovereignty over" Indigenous peoples and their

lands, territories and resources trace to these

dire meanings, handed down from the days of the

Roman Empire, and to a history of dehumanization

of Indigenous peoples. This is at the root of

Indigenous peoples' human rights issues today.

An excerpt follows from "The Letters Patents of King

Henry the Seventh Granted unto Iohn Cabot and his Three Sonnes, Lewis,

Sebastian and Sancius for the Discouerie of New and Unknowen Lands," of

March 5, 1498. Letters Patent and other instructions given to voyagers

to the "new world," illustrate how Great Britain and France initially

had far-reaching plans for imperialist adventures in North America that

took little account of the rights of the Aboriginal inhabitants:

Letters Patent issued to John Cabot

|

"Henry, by the grace of God, king of England and

France, and lord of Ireland, to all to whom these

presents shall come, Greeting. Be it knowen that

we haue giuen and granted, and by these presents

do giue and grant for vs and our heiress to our

welbeloued Iohn Cabot citizen of Venice, to Lewis,

Sebastian, and Santius, sonnes of the sayd Iohn,

and to the heires of them, and euery of them, and

their deputies, full and free authority, leaue,

and power to saile to all parts, countreys, and

seas of the East, of the West, and of the North,

vnder our banners and ensignes, with fine ships of

what burthen or quantity soeuer they be, and as

many mariners or men as they will haue with them

in the sayd ships, vpon their owne proper costs

and charges, to seeke out, discouer, and finde

whatsoever isles, countreys, regions or prouinces

of the heathen and infidels whatsoeuer they be,

and in what part of the world soeuer they be,

which before this time haue bene vnknowen to all

Christians; we haue granted to them, and also to

euery of them, the heires of them, and euery of

them, and their deputies, and haue giuen them

licence to set vp our banners and ensignes in

euery village, towns, castle, isle, or maine land

of them newly found. And that the aforesayd Iohn

and his sonnes, or their heires and assignee may

subdue, occupy and possesse all such townes,

cities, castles and isles of them found, which

they can subdue, occupy and possesse, as our

vassals, and lieutenants, getting vnto vs the

rule, title, and jurisdiction of the same

villages, townes, castles, & firme land so

found.... Witnesse our selfe at Westminister, the

fifth day of March, In the eleventh yeere of our

reigne."

In the European context, all the rights pertained

to the king by divine right and he ruled in

conjunction with the church. In 1215, Magna

Carta was signed by which the feudal

nobility forced the king to hand some of his

rights over to them. The King or Queen issued

royal Charters by the authority of the Royal

Prerogative, which continues to date in the

unrepresentative Westminster parliamentary system

imposed on Canada in 1867. Charters are legal

documents that decreed grants, particularly land

grants, by the sovereign to his or her subjects.

The power and authority of the King and Queen are

almost absolute, as the following commentary on

the laws of England by William Blackstone shows:

"And, first, the law ascribes to the king the

attribute of sovereignty, or pre-eminence.... He is

said to have imperial dignity, and in charters

before the conquest is frequently styled basileus

and imperator, the titles respectively assumed by

the emperors of the east and west. His realm is

declared to be an empire, and his crown imperial,

by many acts of parliament, particularly the

statutes 24 Hen. VIII. c. 12. and 25 Hen. VIII. c.

28; which at the same time declare the king to be

the supreme head of the realm in matters both

civil and ecclesiastical, and of consequence

inferior to no man upon earth, dependent on no

man, accountable to no man."

Between 1754 and 1763 the British generals monopolized power in their

own hands through conquest on behalf of the Crown.

In a series of acts, the British modified the

Royal Prerogative to include a new basis

legitimizing the subjugation of the Indigenous

peoples and to include men of propertied means in

the political power whose power was absolute. The

Royal Proclamation of 1763, one of the most

significant colonial decrees issued after the

ceding by France of Canada to the British (Treaty

of Paris, deciding the Seven Years War),

explicitly forbade grants "upon any Pretence

whatever" of any land "not having been ceded to or

purchased by us" from the Indigenous peoples:

"And whereas it is just and reasonable, and

essential to our interest and the security of our

colonies, that several Nations or Tribes of

Indians with whom we are connected, or who live

under our protection, should not be molested or

disturbed in the possession of such parts of our

dominions and territories as not having been ceded

to or purchased by us are reserved to them or any

of them as their hunting grounds."

It goes on to forbid any more private purchases

and prescribes the procedure by which the Crown

would acquire land so reserved and when it was

needed for settlement.

Hardial Bains wrote in A Future to Face,[1] a book

published at the time of the campaign to defeat

the 1992 Charlottetown Accord:

"The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763 placed

the political power in the hands of an Executive

consisting of a Governor and Council appointed by

the ruling authority, the Colonial Office in

London. It was a direct rule under the sovereign

authority of the British King as advised by the

18th century Parliament. The proclamation included

a provision for a popular assembly 'as soon as...

circumstances admit.'"

In 1767 the whole of Prince Edward Island was

granted in one day by royal decree to a few dozen

"absentee proprietors."

The Quebec Act, 1774, followed by the Constitutional

Act, 1791, marked the use of noblesse

in order to preserve and extend the power

established in 1763. The latter act, along with

the division of Quebec into Upper and Lower

Canada, vested legislative authority in the

Governor or Lieutenant-Governor acting with the

advice of a legislative council and assembly in

each of the two colonies. "A bill passed in both

the Legislative Assembly and the appointed

Legislative Council could be accepted or rejected

by the Governor or he could reserve it for the

pleasure of the Crown. Any bill assented by the

Governor could be over-ruled by the British

government any time within two years. The Governor

and Executive Council were constituted into the

Court of Appeal, with the right to appeal to the

British Privy Council in London as final arbiter."

In 1867, the Confederation as it emerged did not provide a modern conception

of democracy which eradicates enslavement.

Confederation was not negotiated on the basis of a

free and voluntary union with the Indigenous

peoples, nor was it put to the population of the

Canadas for approval or rejection in any

democratic vote in any of the colonies, with the

exception of New Brunswick where it was defeated.

Put into effect in 1867, the British North

America Act -- in modern terms referred to

as Constitution Act, 1867 -- formulated a

central government that preserves the sovereignty

of the Queen. The concentration of executive

power, through conquest, becomes perpetuated

through to the 21st century in the form of

executive federalism and the Westminster

parliamentary democracy. The Dominion of Canada

was the name commonly used until around World War

II. Invoking the providence of the Biblical God of

the Israelites, the neo-colonial state drew upon

the Old Testament and the eighth verse of King

Solomon's 72d Psalm for its name: "And He shall

have dominion also from sea to sea, And from the

River unto the ends of the earth."

The Royal Charter to the Hudson's Bay Company

On May 2, 1670, Charles II granted a Royal Charter

to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) headed by his

cousin Prince Rupert of the Rhine and his Company

of Adventurers of England -- "Company of

Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay

-- delivering proprietary rights, exclusive

trading privileges, and limited governmental power

covering:

"...all the Landes and Territoryes upon the

Countryes Coastes and confynes of the Seas Bayes

Lakes Rivers Creekes and Soundes aforesaid [that

is, "that lye within the entrance of the Streights

commonly called Hudsons Streights"] that are not

already actually possessed by or granted to any of

our Subjectes or possessed by the Subjectes of any

other Christian Prince or State..."

The charter granted one company a monopoly of

trade in the Bay and ownership of all lands

drained by rivers flowing into the Bay. The HBC

established an English colonial presence in the

Northwest and a competitive route with France to

the fur trade. Numerous unsuccessful challenges

emerged concerning the legitimacy and accuracy of

the land grant.

The Hudson Bay Company, Canadian Land Company and

British American Land Company all included British

slave owners on their boards of directors. Much of

the profits of Barings, which enriched itself from

slavery and the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act,

were re-exported to finance the neo-colonial

confederation of Canada created in 1867 and the

railway and territorial expansion of the U.S. and

Canadian colonial states in the 1800s.[2] The slave trade

formed the basis of wealth for many leading

families of the gentry, among them the "father of

Confederation" Sir John A. Macdonald, who had a

direct personal family link to slavery. Most

importantly, Macdonald was himself an ardent

architect of genocide.[3]

The wealth of the Bank of Nova Scotia and the

Royal Bank -- both of which were founded in

Halifax -- was originally generated from the

significant mercantile trade from the Atlantic

fisheries to provide protein to the slave

plantations (the triangular trade) in the

Caribbean, along with the building of slave ships

-- euphemistically described by historians as the

"West Indies trade" -- and later in the sugar,

rum, and coffee trade, exploitation of railways,

shipping, electrical power, bauxite and other

mining resources, and military adventures.

London-based slave owners played a significant

role in the settlement, exploitation, and

expansion of Canada through to the 1800s.

The Royal Family

Henry VII, Giovanni Caboto's royal benefactor, in

1497 -- the year of Cabot's first expedition --

smashed the Second Cornish Rebellion, killing

2,000 and selling thousands of captured rebels

into slavery.

Later, from the enslavement and deportation of

the Irish to British colonies in the West Indies

to the kidnapping of Africans, the British Crown

made much of their vast personal wealth from the

human slave trade.

In The Open Veins of Latin America,

Eduardo Galeano describes how in 1562 Queen Elizabeth I of

England (1558-1603) became a business partner of

the English pirate Captain John Hawkins,

"the English father of the slave trade."[4] Official

English participation in the African Slave Trade

began that year and Blacks were expelled from

England by law in 1596, by a proclamation issued by Elizabeth I:

"[T]here are of late divers blackmoores brought

into this realme, of which kinde of people there

are allready here to manie ... Her Majesty's

pleasure therefore ys that those kinde of people

should be sent forth of the lande."

Accordingly, a group of slaves were rounded up

and given to a German slave trader, Caspar van

Senden, in "payment" for duties he had performed.

In 1632, King Charles I granted a licence to

transport slaves from Guinea, from which is

derived the name of the coin of the realm --

guinea. Charles II was a shareholder in the Royal

African Company, which made vast profits from the

slave trade, paying 300 per cent in dividends,

although only 46,000 of the 70,000 slaves it

shipped between 1680 and 1688 survived the

crossing. Its Governor and largest shareholder,

was James, Duke of York who branded the initials

"DY" on the left buttock or breast of each of the

3,000 Blacks that his concern annually took to the

"sugar islands." Princess Henrietta (Minette),

the King's sister, also had a share. The shareholders of its

predecessor, Royal Adventurers into Africa

(1660-1672), included four members of

the royal family, two dukes, a marquess, five

earls, four barons, seven knights and the

"philosopher of liberty" John Locke.[5]

For its part, the Royal Family has never

apologized for its intimate role in the Atlantic

Slave Trade and the genocide of the Indigenous

peoples nor been forced to pay a single cent in

reparations.

Notes

1. Hardial Bains, A

Future to Face, (MELS, 1992), p.12.

2. Barings, a stronghold of

British finance capital, was financial agent for

Canada in London. Barings Bank was behind the

forced union of the Canadas in 1841. R.T. Naylor

remarked that Baring Brothers were the true

Fathers of Confederation. It acted as the

exclusive financial agents for Nova Scotia and New

Brunswick, as well as Upper Canada along with

George Carr Glyn, a big investor in the colonies.

By the last quarter of the 19th century, Baring

Brothers was financing one-quarter of all U.S.

railroad construction, along with the

Intercolonial, Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific

railways in Canada. A railroad town in British

Columbia was renamed Revelstoke, in honour of the

leading partner of the bank, Edward Baring, 1st

Baron Revelstoke, commemorating his role in

securing the financing necessary for completion of

the CPR.

Some of the information on Barings and the land

companies is drawn from Dr. Laurence Brown, "The

slavery connections of Northington Grange,"

University of Manchester, 2010; Peter Austin, Baring

Brothers and the birth of Modern Finance,

London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 63; and

Nicholas Draper et al, Legacies of

British Slave-ownership: Colonial Slavery and

the Formation of Victorian Britain,

Cambridge University Press, 2014. Draper and

others have developed at University College London

a research centre for the study of the legacies of

British slave-ownership. More information about

their work and links to a database of compensation

paid at abolition to former slave-owners can be

found at

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/project.

3. Macdonald's

father-in-law, Thomas James Bernard, owned a sugar

plantation near Montego Bay, Jamaica and 96

enslaved Africans. He received £1,723

"compensation" from the British government under

the Abolition of Slavery Act of March

1833, a vast sum considering the annual salary for

a skilled worker in Britain at the time was around

£60. Macdonald married Bernard's daughter, Agnes,

1st Baroness Macdonald of Earnscliffe, in 1867.

Macdonald had to resign in 1873 when the Pacific

Scandal exposed his receipt of campaign donations

from the owner of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

See also "Sir

John A. MacDonald's Reign of Terror," Tony Seed,

TML Weekly, October 3, 2017.

4. Hawkins' first slave

expedition in 1562 was made with a fleet of three

ships and 100 men. He smuggled 300 Blacks out of

Portuguese Guinea "partly by the sworde, and

partly by other meanes." A year after leaving

England, Hawkins returned to England "with

properous successe and much gaine to himself and

the aforesayde adventurers." Queen Elizabeth was

furious: "It was detestable and would call down

vengeance from heaven upon the undertakers," she

cried. But Hawkins told her that in exchange for

the slaves he had a cargo of sugar, hides, pearls,

and ginger in the Caribbean, and "she forgave the

pirate, and became his business partner."

Elizabeth I supported him by lending him for a

second expedition, The Jesus of Lubeck, a

700-ton vessel purchased by Henry VIII for the

Royal Navy.

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America:

Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent,

Translated by Cedric Belfrage. New York: Monthly

Review Press, 1997. p.80; James Walvin, Black

Ivory: Slavery in the British Empire,

London: HarperCollins, 1992, p. 25.

5. The idea of the innate

inferiority of non-Europeans is prominent in the

John Locke's "Essay Concerning Human

Understanding" (1690).

(To access articles

individually click on the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS ISSUES

| HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|

The demand for a

right is the expression of the extent to which the

human personality has developed in relation to the

conditions of the times. We are talking here about

the human personality as a genre, as the quality

of the times, as the product of social being. The

demand for equality, then, is an historical

product. The modern demand for equality consists

in deducing from that common quality of being

human, from the equality of human beings as human

beings, a claim to equal political and social

status for all human beings, or at least for all

citizens of a state or all members of a society.

The demand for a

right is the expression of the extent to which the

human personality has developed in relation to the

conditions of the times. We are talking here about

the human personality as a genre, as the quality

of the times, as the product of social being. The

demand for equality, then, is an historical

product. The modern demand for equality consists

in deducing from that common quality of being

human, from the equality of human beings as human

beings, a claim to equal political and social

status for all human beings, or at least for all

citizens of a state or all members of a society. This is the context

in which the modern demand for equality takes

shape. The economic relations required freedom and

equality of rights, but the political system

opposed them. It was left to the great men of the

18th century, especially in France, to transcend

the thinking of the preceding age. The work which

is the most representative of this age, the Age of

Enlightenment, was the Encyclopédie,

published between 1750 and 1789 in Paris by Denis

Diderot with the assistance of Jean le Rond

d'Alembert, and which included contributions by

some forty other 'philosophes,' including

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, François Marie Arouet de

Voltaire, the Baron de Montesquieu, François