|

February 17, 2021 - No. 7

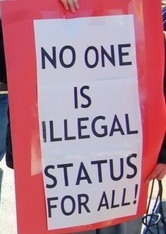

The Fight for Status for All

Permanent Resident Program for Refugee

Claimants Dismally Fails Migrant Workers

• Who

Can Apply for Permanent Residence Status Under

the Immigration Department's "Special

Measures?"

Honduras

• Mass Migration, a

Post-COVID-19 Legacy - Javier Suazo

The Fight for Status for All

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

(IRCC) is now accepting applications for its

"special measures for refugee claimants working

in health care during the pandemic." People can

apply until August 31, 2021.

This program was put in place after Quebec

Premier François Legault's declaration on May

25, 2020 that he would consider allowing refugee

claimants working in Quebec long-term care

facilities during the pandemic to permanently

settle in Quebec. The program was officially

announced in August and the IRCC started

accepting applications on December 14, 2020.

The temporary program allows certain refugee

claimants, only those who "provide direct care

to patients" during the COVID-19 pandemic, to

apply for permanent resident (PR) status. It

also permits applications from spouses and

common-law partners of eligible asylum seekers

who contracted COVID-19 and died, if the

applicants are in Canada and arrived before

August 14, 2020.

According to Federal Immigration Minister Marco

Mendicino this temporary program is to recognize

"the dedication of the many asylum seekers who

have raised their hands to serve as we live

through a unique and unprecedented situation."

Under the Canada-Quebec Accord the Quebec

government has sole responsibility for deciding

who will become permanent residents so the

federal government has developed two temporary

policies, one for people living in Quebec and

another for those residing outside of Quebec. It

is estimated that most of the eligible workers

are in Quebec.

Applicants

residing in Quebec must first submit an

application for permanent resident status to

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

(IRCC). If they qualify under the federal

requirements, the Quebec Ministry of

Immigration, Francization and Integration (MIDI)

must then validate whether they also meet the

requirements under its special program. If they

do the MIDI issues a Quebec Selection

Certificate (CSQ) and the IRCC grants permanent

resident status. Applicants

residing in Quebec must first submit an

application for permanent resident status to

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

(IRCC). If they qualify under the federal

requirements, the Quebec Ministry of

Immigration, Francization and Integration (MIDI)

must then validate whether they also meet the

requirements under its special program. If they

do the MIDI issues a Quebec Selection

Certificate (CSQ) and the IRCC grants permanent

resident status.

Quebec's Immigration Minister, Nadine Girault,

said that the purpose of the special program "is

to recognize the exceptional contribution of

asylum seekers who worked on the front line,

with people who were sick and with our seniors,

during the first wave of the health crisis," and

allow them to "continue their essential

contribution to health care and integrate fully

into Quebec society."

Those eligible for the "special measures"

represent a small fraction of the thousands of

asylum seekers who worked, and continue to work,

providing essential services in health care as

cooks, cleaners, and in other positions that do

not provide "direct care to patients," as well

as those working in other economic sectors.

These workers are not recognized for their

sacrifice and contribution to keeping society

functioning and safe, and are not eligible for

the program.

In a news release and backgrounder issued on

December 9 by Immigration, Refugees and

Citizenship Canada, the criteria for granting

permanent resident status to certain asylum

seekers is laid out.[1]

The news release states:

"Among other criteria, individuals eligible for

consideration under these public policies must:

- be a refugee claimant, with either a failed

or pending refugee claim, who claimed asylum

before March 13, 2020, and continued to reside

in Canada when their application for permanent

residence under this public policy was made;

- have been issued a work permit after they

made their refugee claim;

- have worked in a designated occupation

providing direct patient care: in a hospital,

public or private long-term care home or

assisted living facility, or for an

organization/agency providing home or

residential health care to seniors and persons

with disabilities in private homes;

- have a Quebec Selection Certificate, if

wishing to reside in Quebec; and

- meet existing admissibility requirements,

including those related to criminality, security

and health.

"Some refugee claimants would be excluded from

applying, including those who have been found

ineligible to have their refugee claim referred

to the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada,

or who have withdrawn or abandoned their

claims."

Applicants must advise the Immigration and

Refugee Board (IRB) that they have applied, so

that any pending refugee claim can be placed on

hold. Once IRCC confirms their eligibility and

that they have the required work experience, any

removal order they are under will be stayed

until a final decision on their application is

made.

The pending or failed refugee claimant must

also have been authorized to work in Canada by

virtue of a work permit "unless the individual

lost their authorization to work as a result of

a removal order against them becoming

enforceable due to a final negative decision of

their refugee claim, in which case work

performed subsequent to the loss of that

authorization need not be authorized." In other

words, if someone lost their work permit after a

removal order was issued against them and

nonetheless continued to work to ensure their

survival, they may apply for the program.

However, if they are rejected, it leaves them

without any recourse and at risk of immediate

removal from Canada.

If applying for permanent resident status under

these "special measures" anyone who has received

a final negative decision from the IRB and has

"commenced an application for leave and judicial

review of the negative IRB decision in Federal

Court, or an appeal in relation to the

underlying IRB decision at the Federal Court of

Appeal" must withdraw their claim at the IRB or

their appeal of the negative decision "in order

to be granted permanent residence through the

public policy." Should they not withdraw, "those

processes will continue to proceed but their

application for permanent residence under this

public policy will be refused."

Persons not eligible include: "Persons whose

refugee claims were: determined to be ineligible

to be referred to the IRB; determined to be

withdrawn (unless withdrawn immediately prior to

being granted permanent resident status through

this public policy) or determined to be

abandoned; determined to be manifestly unfounded

(MUC) or with no credible basis (NCB);

determined to be excluded under Article 1F of

the Refugee Convention; or a determination that

refugee protection has been ceased or vacated

are not eligible for this public policy."

1. "IRCC

announces

opening date of special measures for refugee

claimants working in health care during the

pandemic," Immigration, Refugees and

Citizenship Canada, December 9, 2020

Honduras

- Javier Suazo -

January, 2021. Caravan of Honduran migrants

travels through Guatemala.

"Trump's response

has been to enact draconian immigration

policies that seek to repeal our asylum and

refugee laws, along with severe reductions in

our

foreign assistance to the region." -- Joe

Biden

In the agrarian reform programs of the '70s

and part of the '80s, internal migration was

part of State policy for the organization and

training of peasant farmers, in order for them

to access good quality productive, uncultivated

land in the possession of large landowners. As

well, there was a strategy of transferring

peasant families from less developed areas to

those with greater potential, although part of

the promised land was State-owned.

These policies and actions had, on the one

hand, the support of international cooperation,

which provided food and clothing to "migrant"

peasants, as well as of the State itself, with

programs to provide technical assistance, credit

and tools. But these programs were also

supported by multilateral banks for the

execution of agricultural development projects,

sustained through the export of crops such as

bananas, cashews, cotton and citrus fruits, with

transnational companies and local intermediaries

controlling the commercialization of the

products as a way of transferring the risks of

production to the farmers and government

themselves.

It has not been the same with migrations

outside the country, where although the risk is

borne by individual migrants and families (today

they seek the American dream -- the father,

mother, children and other relatives), this has

expanded after the political crisis generated by

the coup d'état in June 2009. Before that, in

general, external migration was voluntary and

spontaneous. People who managed to cross the

border between Mexico and the U.S. sent money to

their relatives to set out, or hired a "coyote"

to help them on their route to the north. Some

of them stayed working in Guatemala or Mexico,

to accumulate the money to guarantee a safe

journey, others simply returned, or were

deported by the Mexican or gringo

immigration authorities.

Today migration to the U.S. has become

complicated. On the one hand, the paralysis and

abandonment of the agrarian reform programs led

to the expulsion of the peasant population from

the countryside to the city, and eliminated the

induced migration programs supported by the

State and international cooperation. Along with

this came increased concentration of ownership

and rural precariousness, which translated into

greater poverty and food insecurity. Since the

'90s, the fashionable programs have been

Conditional Cash Transfers and food aid, putting

the country deeper into debt and using the

surplus of basic grains that U.S. producers

"subsidized" by the State cannot sell in their

regional market, negatively impacting local

production.

This was further complicated by the deepening

of orthodox economic stabilization and

structural adjustment policies and programs

supported by the International Monetary Fund

(IMF) and World Bank, resulting in the

contraction of State spending, hurting peasants

involved in domestic agriculture. All of this

has added to greater concentration of property

ownership and dispossession of natural resources

and biodiversity from the communities. Contrary

to what was intended by their design, these

policies have generated greater migration, but

also less economic and social protection for

vulnerable and poor families.

COVID-19 and natural phenomena such as

hurricanes Eta and Iota have made this situation

of inequality and the lack of opportunities more

visible for rural families, and is now also

affecting mostly young people in populated

centres, where jobs are a rare commodity, and

violence, drug trafficking and corruption

directly involve the government.

The government and politicians' discourse is

that migrants are the problem, so it is

necessary to try by all possible means to get

them to refrain from migrating, although in

reality it is a human right. A father of a

family who lost his land for not paying his

debts to the bank because the harvest was lost,

who, in the city was fired from his precarious

job due to the lockdown and avoiding contagion

with COVID-19, then had his house destroyed by

Eta, has few options to feed his family and

survive, so the closest thing at hand is

migration or death.

The government of the Republic hopes that

things will return to "normality," as it existed

before COVID-19, but with policies that promote

the concentration of rural property ownership,

the destruction of natural resources, economic

and social exclusion due to the lack of

large-scale popular housing programs, access to

education, health and sustainable jobs organized

by the State, this normality is not like that;

rather it was and will be an exclusionary

normality.

Donald Trump's policy, accepted without any

fuss by the governments of Honduras, Guatemala

and Mexico, also made it possible, in practice,

for migration to be criminalized as an offence,

despite the discourse of public officials and

police that it is and continues to be a human

right. These countries became an extension of

the migra

gringa, [the U.S. Immigration and

Customs Enforcement agency] since their police

forces are responsible for persecuting the

migrants. They are organized and held in public

centres (which some call cages) or in social

centres, waiting for their asylum application to

be processed, which does not arrive; but others

are simply deported and separated from their

children, without having processed their request

through the authorities of a safe country, be

that Guatemala or Mexico.

January 14, 2021. Migrants leave San Pedro

Sula, Honduras heading north.

On January 14, 2021, a new migrant caravan left

San Pedro Sula, the industrial capital of

Honduras, some 3,000 people according to

official figures, concentrating more than 6,000

people on the border with Guatemala on Sunday,

January 17 (new caravans were added on the

weekend), according to data reported in the

non-monopoly press, that included children, but

also older adults, pregnant women and disabled

people. The Honduran Police, instead of

encouraging them to continue and wishing them

good luck, tell them to watch out for the migra of

Guatemala and Mexico, and to forget about

getting to the U.S. border. In addition to

personal papers (identity and children's birth

certificates), a COVID-19 test is required to

enter Guatemala, as those who do not comply will

be deported.

The mobilization of Guatemalan police and

military to the border with Honduras has been

dramatic, as with the Mexican police to the

border with Guatemala, where the slogan is No Pasarán,

like the commitment made to Donald Trump when

they accepted to operate as "safe countries" for

migrants. The press talks about Hondurans being

deported before they enter Guatemala, that is,

by Customs and associated officials, but the

migrants do not plan to return and are facing

the police and the military, hoping to get past

some 20 security cordons between the border with

Guatemala and Mexico.

January 17, 2021. Migrants brutally attacked by

Guatemalan police and military.

The deportees will be registered by the

Honduran authorities, since there is an

Executive Decree No. PCM-033-2014 that declares

a humanitarian emergency due to mass migrations

and obliges the government to activate the

social protection system whose main policy is

the Conditional Cash Transfers and food aid,

added to temporary and poor-quality employment

when there are resources and projects that

require, for the most part, unskilled labour.

Likewise, centres for the care of children and

migrant families are supposed to be activated,

but there is no guarantee of an effective

reintegration into the labour market, or to

schools and homes.

Migrants face Guatemalan police.

Figures from the National Migration Institute

(INM) of Honduras show that in 2020, there were

43,757 Hondurans deported from the United

States, Mexico and Guatemala, of which 10,484

were minors. A curious fact, the largest number

of deportees are from Mexico, not the U.S.,

which shows that Trump's policy has been

effective, although the costs are borne by the

safe country, in this case Mexico.

The migration of Hondurans is taking place

within days of Joe Biden's inauguration as

President of the United States. In the

imagination of the migrants, there is hope that

the new occupant of the White House will relax

or eliminate the policies, actions and laws

approved by the Trump administration, which at

the end of its mandate has dedicated itself to

obstructing the incoming government's actions

and delaying the coming into effect of new laws.

Likewise, they are betting on Biden keeping his

campaign promise to grant residency to the

largest possible number of Latin Americans

living in the U.S. There are also demands that

children not be separated, and that those who

are unaccompanied be given due protection and be

reunited, eliminating Trump's so-called "zero"

tolerance.

It is hoped that

Biden will resume the initiative of the Plan for

the Alliance of the Northern Triangle of Central

America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras) that

he led when he was vice president in the Obama

administration, but which was discontinued or

remained on paper, as it was a government that

specialized in deportations. This plan had a

budget of $750 million to accelerate the

necessary reforms in the region, focused on

fighting organized crime, reducing poverty and

strengthening public institutions contaminated

with the virus of corruption and inefficiency.

One problem, in addition to Trump's freezing of

funds, was trusting leaders and governments

contaminated with corruption and in collusion

with organized crime. It is hoped that

Biden will resume the initiative of the Plan for

the Alliance of the Northern Triangle of Central

America (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras) that

he led when he was vice president in the Obama

administration, but which was discontinued or

remained on paper, as it was a government that

specialized in deportations. This plan had a

budget of $750 million to accelerate the

necessary reforms in the region, focused on

fighting organized crime, reducing poverty and

strengthening public institutions contaminated

with the virus of corruption and inefficiency.

One problem, in addition to Trump's freezing of

funds, was trusting leaders and governments

contaminated with corruption and in collusion

with organized crime.

This initiative was taken up by Mexico with the

support of the Economic Commission for Latin

America (ECLAC), when formulating and approving

the Comprehensive Development Plan for El

Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, but

the Central American governments and migrant

support organizations are still waiting for

financial resources in the amounts promised. In

addition, although it had the support of the

United Nations and the EU, this plan was born

lame, since it runs counter to Donald Trump's

policy for the region, who even developed an

agenda parallel to the Plan's proposals. As

well, it is based on governments and political

leaders under investigation for acts of

corruption and accused of having links with drug

trafficking. It is expected that with Biden the

work agenda of the Plan will be resumed, but

ECLAC should adjust its proposals and look to

foster a more benign approach to the all-round

development of the countries, consulting the

people and their supporting organizations.

Within Honduras, the evidence shows that the

policies and laws in support of migrants do not

work, given that the economic, agricultural and

social policy implemented since the coup d'état

is exclusionary by definition, with a failed

economic model accepted as valid. This extends

to the actions of the National Commissioner for

Human Rights, with the Human Security Strategy

for Local Development, which is seen as a

palliative for the policy of centralized power

and the systematic violation of human rights,

that has little impact on the quality of life of

families in the municipalities and the demand

for citizens' rights.

Choluteca, Honduras, January 17, 2021

(To access articles

individually click on the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS ISSUES

| HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: office@cpcml.ca

|