|

July 2, 2020 - No. 46

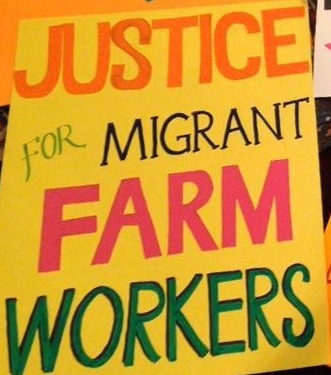

Justice for Migrant Workers!

Ontario Government's Dehumanizing Plan for Migrant Agricultural Workers

• Something Rotten in Ontario's Greenhouse Operations -- and it Isn't the Tomatoes

- Margaret Villamizar

• Spirited Actions in Leamington Demand Justice for Migrant Workers

• Advocating for Seasonal Agricultural Workers in British Columbia

- Interview, Perla G. Villegas-Diaz

• Playing with the Lives of Temporary Foreign Workers in Quebec:

It Must Not Pass!

- Diane Johnston

Justice for Migrant Workers!

There are now over 1,000 agri-farm workers, most of them

migrant workers, who have tested positive for COVID-19 in Ontario. Over

700 of these have been associated with workplaces in Leamington and

Kingsville. Over the weekend 191 new cases were confirmed by the

Windsor-Essex Public Health Unit, all of them from a single operation.

Although the health unit has not named the company, the Windsor Star

reports that it was told by a national representative of the United

Food and Commercial Workers Union that it is Nature Fresh Farms in

Leamington.

Government's New Public Health Guidance:

Work-Isolation Instead of Self-Isolation

On

June 24, one day after calling out "farmers" for not cooperating in

getting their workers tested for COVID-19, Premier Doug Ford did a

180-degree flip. In twenty-four hours he went from blaming and pleading

with the "farmers" in Essex County to do the right thing, to praising

them for stepping up to the plate. Now, they were helping get

more of their workers tested to determine the extent of the outbreak

among agricultural workers in order to get it under control and keep it

from spreading throughout the community. On

June 24, one day after calling out "farmers" for not cooperating in

getting their workers tested for COVID-19, Premier Doug Ford did a

180-degree flip. In twenty-four hours he went from blaming and pleading

with the "farmers" in Essex County to do the right thing, to praising

them for stepping up to the plate. Now, they were helping get

more of their workers tested to determine the extent of the outbreak

among agricultural workers in order to get it under control and keep it

from spreading throughout the community.

A

related about-face was his announcement that Windsor and Essex County,

with the exception of Leamington and Kingsville, would be allowed to

advance to Stage 2

reopening, a reversal of his position the day before when he said the

entire area had to remain at Stage 1 -- the only jurisdiction in the

province with that level of restrictions. That had small business

people up in arms, leading many to vent their anger against big

greenhouses going full tilt in the middle of outbreaks and resisting

having their

workers tested, while they were forced to keep their small shops and

restaurants closed and feared they might lose those businesses.

So what changed? It became apparent a deal had been struck when

Ford announced his government's three-point Plan to

Reduce Transmission on Farms and in the Community in

Windsor-Essex. The

first point calls for expanded testing at agri-food businesses and

in

the community. The second point is an attempt to provide

reassurance that no worker would lose their job if they had to

take

"unpaid sick leave" because of COVID-19, that they could apply for

workers' compensation, and some possibly even for EI or CERB. It

also

says that temporary foreign workers all have "protections like any

other worker in Ontario" under such things as the Employment Standards

Act.

No

mention is made of the many exemptions that apply to farm workers and

more so to migrant farm workers when it comes to employment standards

and labour laws in Ontario, leaving them basically at the mercy of

their employers, without being able to unionize or bargain collectively

to have a say over their working conditions (and where

it applies, deplorable living conditions). No

mention is made of the many exemptions that apply to farm workers and

more so to migrant farm workers when it comes to employment standards

and labour laws in Ontario, leaving them basically at the mercy of

their employers, without being able to unionize or bargain collectively

to have a say over their working conditions (and where

it applies, deplorable living conditions).

Point three reveals the crux of the deal the government struck with

growers to get their buy-in for mass workplace testing rather than

resisting it. A new public health guidance is introduced for the sector

that provides for "allowing" workers who test positive but are

asymptomatic to keep on working, "as long as they follow the public

health

measures in their workplace to minimize the risk of transmission to

others." Ford mused that the new rules would allow COVID-19 positive

but asymptomatic workers to continue to work, grouped together,

outside, and eating and sleeping separately from other workers.[1]

The new guidance appears to give an infected worker who does not

show or report symptoms the option of self-isolating rather than

continuing to work ("work isolate") if that is their "choice." There is

no "choice" for migrant farm workers who who came here to earn a living

to support their families at home when being off work even while

sick, for most means they will not get paid. These workers' lives are

being put at risk by the government of Ontario in keeping with the

self-serving wishes of agribusiness owners.

What is also left unspoken is that a significant section of

temporary foreign workers who work in the fields, greenhouses and

vegetable packing facilities in Essex County are undocumented workers.

They are paid under the table in cash, usually through a recruiter or

some other agent who hires them out to companies, taking their own

pound of

flesh.

These workers operating below the radar have no access to

the income supports and protections the government claims all migrant

workers enjoy if they must, or "choose" to, self-isolate rather than

continuing to work should they test positive.

Responses to Government's New Plan

The

government's new plan was immediately praised by industry owners who

clearly played a big role in coming up with it. One of these was Peter

Quiring, president and CEO of Nature Fresh Farms that has been

identified unofficially as the site of a major outbreak of COIVD-19.

Quiring, who says approximately 360 "guest workers" are included in his

staff of around 670 workers, called the government’s new guidance

"fantastic" when

it was announced. "I was personally working with Doug Ford and Ontario

health on this, as well as many others," he said. "We really like the

conclusions that we've come to. We think this is going to work

well." The

government's new plan was immediately praised by industry owners who

clearly played a big role in coming up with it. One of these was Peter

Quiring, president and CEO of Nature Fresh Farms that has been

identified unofficially as the site of a major outbreak of COIVD-19.

Quiring, who says approximately 360 "guest workers" are included in his

staff of around 670 workers, called the government’s new guidance

"fantastic" when

it was announced. "I was personally working with Doug Ford and Ontario

health on this, as well as many others," he said. "We really like the

conclusions that we've come to. We think this is going to work

well."

Quiring said isolating asymptomatic workers on farms and

"the fact that we can keep working" is the most important part of the

new plan. He said at the time that he was not concerned that

asymptomatic workers would transmit COVID-19 to other employees,

"because we're distancing."

Nature Fresh is the largest bell pepper

producer in North America, shipping 7 million kilograms of product a

year.

Migrant worker advocates were equally quick to respond. Syed Hussan,

executive director of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, denounced

the government and agri-food owners for treating migrants as

expendable, calling their plan "dehumanizing" and "debilitating." He said "You

would not allow your father, your son, your brother, your

mother, your sister, your daughter to be treated like this," adding that "Ontario has responded to three farmworker deaths by

signing a death warrant for more migrant workers."

Justice for Migrant Workers (J4MW) spokesperson Chris Ramsaroop

called for the agri-food industry to immediately cease production until

proper sanitation and safety measures are implemented, saying the

interests of the workers must be paramount, instead of the profits of a

billion-dollar industry.

Doctors and other health care experts have responded with

incredulity at the inhuman new guidance and the unscientific

gobbledygook being used by the government and employers to justify it.

On June 30 a group of them posted an open letter to Ontario's Chief

Officer of Medical Health on the internet calling on him to use his

powers under

the Health Protection and Promotion Act to immediately rescind

the measure. They have invited other health care professionals to sign

and share the letter. It can be found here.

Windsor-Essex Medical Officer of Health Dr. Wajid Ahmed said on June

30 that he had not cleared any of the hundreds of workers who had

tested positive and whose cases had been examined, to return to work,

whether they were asymptomatic or not. He reported that at the time

there were between 400 to 450 migrant workers in

self-isolation and said farms needed to act proactively by immediately

isolating any worker who tested positive and getting any close contacts

tested.

Then on July 1, in addition to announcing 7 new cases in

the agri-farm sector, the health unit issued an update regarding the

outbreak at an operation it did not name but is presumed to be Nature

Fresh Farms where 191 new cases were identified over the weekend. It stated:

Given the size of

this outbreak, the potential for COVID-19 transmission, and the ongoing

risk to the health and safety of the workers, Medical Officer of Health

Dr. Wajid Ahmed is issuing an order under section 22 of the Health Protection and Promotion Act (HPPA)

effective July 1. The order requires the owner/operator of the farm to

ensure the isolation of workers and prohibits them from working until

further direction. [....]

The safety and well-being of all

workers is our top priority. It is imperative that we stop the

transmission of COVID-19 in this farm and our agricultural sector. All

affected workers must be isolated and their health and wellbeing be

monitored before any return

to work can be discussed.

An official later

clarified that the order to isolate applied to all workers at the

location, not just those who had tested positive, effectively shutting

the operation down for the time being.

Note

1. The government's new guidance gives

responsibility to the local public health unit to provide direction to

workers deemed to be asymptomatic who have tested positive. It says

these workers must self-isolate or "work-isolate" if that is determined

appropriate by the health unit, for 14 days. Should symptoms develop,

they should self-isolate

for 14 days from the time of symptom onset. Close contacts of the

asymptomatic workers who are not tested can also either self-isolate or

work-isolate if that is determined appropriate by the health unit.

- Margaret Villamizar -

Instead of affirming the rights of workers infected

with the coronavirus and permitting them to recover fully and not risk

infecting others, the Ontario government working directly with some of

the largest greenhouse operators and without any voice for the workers,

has decided to allow workers who have tested postive for COVID-19 to

work

in the fields and greenhouses as long as they are not displaying or

reporting symptoms.

In other words, workers will have to choose whether or

not to report the symptoms they might be experiencing. It is equivalent

to having the "choice" whether to feed your family or not since paid

sick leave is not a requirement in Ontario or of the federal

government's Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program. This program last

year brought in around 25,000 workers from Mexico and smaller numbers

from Jamaica and several other Caribbean countries through contracts

between the Canadian government and governments of the sending

countries. Then there is the issue of those who have been

identified as close contacts of these workers, some of whom would have

the same "choice" to make.

Not a small number of workers in this industry work

under the table since they are undocumented (at least 2,000 are

believed to be in this category in Essex County) or for other reasons.

Sometimes these precarious workers travel between workplaces, assigned

by recruiters to different operations as short term "contract workers."

This has likely already contributed to the spread of the virus, and to

the death of 24-year-old Rogelio Muñoz Santos, one of the three

Mexican migrant workers who have died in Ontario from COVID-19. To

presume this practice will now disappear because it is no longer

"allowed" is a fairy tale or more likely an attempt to hide what is

rotting in the greenhouse operations.

The

large agribusinesses operating in Essex County make their profits by

treating migrant workers as if they are expendable, preying on their

economic vulnerability as a result of the economies of their homelands,

especially the agricultural sector, being ddestroyed by neo-liberal

globalization and "free trade" agreements like NAFTA and CUSMA. The

large agribusinesses operating in Essex County make their profits by

treating migrant workers as if they are expendable, preying on their

economic vulnerability as a result of the economies of their homelands,

especially the agricultural sector, being ddestroyed by neo-liberal

globalization and "free trade" agreements like NAFTA and CUSMA.

Governments, instead of affirming the rights of the

workers, are determined to maintain the profits of these agribusinesses

at the expense of the workers using laws which prevent them from

organizing. They ensure, through contracts negotiated with the

governments of Mexico and 12 Caribbean countries, that seasonal

agricultural workers are supplied for up to eight months a year and

that wages are kept to the minimum.

The fact that much of the production from this part of

Southwestern Ontario goes to U.S. markets shows a serious problem with

the direction of Canada's economy[1].

Food production is not geared towards food security for the Canadian

people, despite the industry being deemed "critical" to Canada's food

supply after growers engaged in high-level lobbying to ensure they

could get the workers they require into the country despite the border

being closed to international travel. It is all about keeping large

multi-million dollar industrial enterprises, some of them multinational

-- and certainly not family farms as some like to call them --

profitable in a highly competitive sector. One of the ways this is done

is by limiting the claims of the workers, and at the expense of the

well-being of the human beings who generate the industry's profits

turning nature into the massive bounty that comes from modern

greenhouse operations.

The collaboration of various levels of governments with

this inhumane setup shows that governments operate as an extension of

these large enterprises and view the workers' claims as a problem.

Why does the agriculture industry have to run on such an

inhuman basis? Why are governments forcing infected workers to keep

working? What does this tell us about the aim of Canada's food

production system? Or the safety of it? What is the point of the

economy when workers' lives are expendable but maximum profits are

essential?

The greenhouse operations in Southwestern Ontario are

part of the integrated North American economy. They supply fresh

produce of all kinds to the United States and produce profits for their

owners on the basis of depressed wages and working conditions of local

and foreign workers, access to water from the Great Lakes, and

government

subsidies and services of various kinds.

What has been exposed through the pandemic confirms that

a new direction is needed. Food production should be organized to meet

the need of Canadians for healthy food and of workers, irrespective of

where they come from, for livelihoods at a Canadian standard.

Ironically, July 1 marks the coming into force of the new NAFTA

(CUSMA). During its renegotiation, the Canadian government and its

team made a big deal of insisting that Mexico raise its labour and

human rights standards. The facts reveal that Canada is in no position

to give lessons to Mexico.

Note

1. The Financial Post reported in

April 2020

that according to Statistics Canada, exports accounted for 65

per cent of the total

value of Canada’s greenhouse vegetable production in 2016, the

last year for which

numbers are reported.

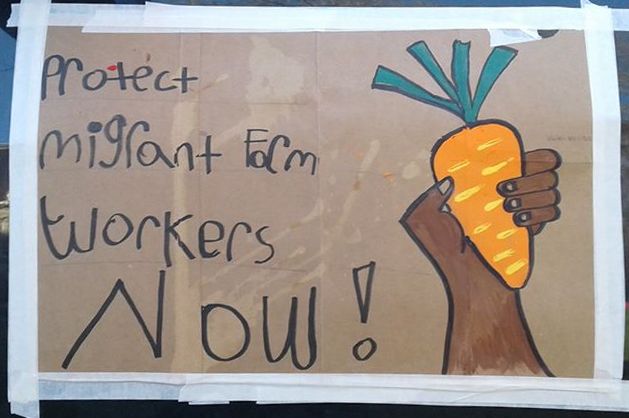

March for migrant workers' rights, Leamington, June 28, 2020.

On Sunday June 28 actions were held in Leamington,

Ontario to show the support of the working people of Ontario for

agricultural workers in the Leamington-Kingsville area, a centre of

greenhouse growing and packing operations in Essex County. The actions

were organized by Justice for Migrant Workers and local youth, and were

joined by working people of many ages and backgrounds.

A

long line of vehicles set out from the Walmart parking lot and drove

past a number of agri-food workplaces. People painted messages on their

vehicles or attached signs to them in English and Spanish expressing

solidarity with migrant workers and demanding their rights be upheld

and guaranteed. Many members of local unions flew their flags from

their car windows and carried them in the march following the caravan.

Among them were flags from the Canadian Union of Public Employees,

Canadian Union of Postal Workers, Ontario Public Service Employees'

Union, Canadian Office and Professional Employees, Ontario English

Catholic Teachers' Association, Elementary Teachers' Federation of

Ontario, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Unifor, the

Windsor and District Labour Council and the Ontario Federation of

Labour. Among those participating in the caravan was OFL President

Patty Coates. A

long line of vehicles set out from the Walmart parking lot and drove

past a number of agri-food workplaces. People painted messages on their

vehicles or attached signs to them in English and Spanish expressing

solidarity with migrant workers and demanding their rights be upheld

and guaranteed. Many members of local unions flew their flags from

their car windows and carried them in the march following the caravan.

Among them were flags from the Canadian Union of Public Employees,

Canadian Union of Postal Workers, Ontario Public Service Employees'

Union, Canadian Office and Professional Employees, Ontario English

Catholic Teachers' Association, Elementary Teachers' Federation of

Ontario, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Unifor, the

Windsor and District Labour Council and the Ontario Federation of

Labour. Among those participating in the caravan was OFL President

Patty Coates.

The caravan drove past many greenhouses, horns honking

in a show of solidarity, aware that workers were inside some

buildings despite it being Sunday. Many drivers the caravan passed

honked their horns as well, signalling their support for workers who

are an important part of their community. One of the large operations

on the caravan’s route was the multinational cannabis giant

Aphria, as well as a greenhouse operation it has a joint venture with

Double Diamond Farms. A bunkhouse for migrant workers employed by

Double Diamond Farms was the subject of a video that has been

circulated widely showing how 12 workers are forced to live in cramped

quarters with only cardboard and thin cotton sheets separating their

bunks.

The caravan ended at the Big Tomato, a landmark in downtown Leamington where participants rallied and shouted slogans.

Elizabeth Ha, an activist with Justice for Migrant

Workers and OPSEU member who is on the Windsor and District Labour

Council Executive was the caravan's main organizer. She said a lot of

people in the community didn't really know about the conditions migrant

workers have faced for a long time, but as a result of the pandemic

they were starting to see those things now. She said the caravan and

march let the workers know the community stands in solidarity with them

and wants to thank them. They are essential workers. But, said Ha, they

don't have the same rights that we do. She said the government needed

to make changes and cannot keep avoiding it.

A March for Migrant Workers'

Rights followed the caravan, organized by local young women activists. It

went through the streets of Leamington with participants shouting

slogans and displaying signs and banners. It ended with a rally outside

Lakeside Produce, another of the large greenhouse, packing and

distribution

operations. There organizers held a speak-out denouncing the Ontario and Canadian governments for their support for

the exploitation of vulnerable workers in this sector. They

specifically demanded an accounting for the $15 million the

Ontario government gave greenhouse operators to purchase PPE for

their

workers, which some workers report their employers are forcing them to pay for.

Speakers denounced the entire agribusiness sector that is based on the super-exploitation of migrant and

undocumented and poor workers, pointing out that whether in meat

processing or vegetable processing, the industry is based on

exploitation and

is not sustainable, referring to calls from some quarters that a

solution to problems in agribusiness or those related to climate change

lies in moving from meat-based to plant-based foods and production.

Speakers also informed the crowd about the three migrant workers from

Mexico who had died of COVID-19, humanizing them by

repeating their names and appealing to everyone to consider them like

they would their own family.

- Interview, Perla G. Villegas-Diaz -

Migrant workers' organizers in Kelowna, BC, June 17, 2019.

Workers' Forum

interviewed Perla G. Villegas-Diaz, an activist and researcher with

Radical Action with Migrants in Agriculture (RAMA), who herself is from

Mexico. She is in Canada with her family studying International

Development at Okanagan College.

Workers' Forum: Tell us about your work with seasonal agricultural workers.

Perla G. Villegas-Diaz:I

came to Canada almost three years ago. I am a lawyer in Mexico,

worked for 15 years with a federal human rights tribunal, and while I

am studying here I learned of the situation of migrant farm workers in

this community and last year I accepted work as a research assistant

with RAMA. To be honest I didn't know

anything about the conditions of workers who come to Canada every year

to work on farms. When you live in Mexico you think that those who go

to Canada or the U.S. are "living the dream." Last year I met a lot of

workers and I remember two in particular who told me "Can you imagine

working more than 10 hours a day without being

allowed to use a washroom or being allowed to drink water, even when it

is 38 degrees?" They live in crowded conditions.

WF:

Have there been any changes this year because of the COVID-19? Are

there any new measures being put in place to improve the living

conditions to protect the workers?

PV:

No, it's exactly the same. We thought that there would be improvements

because the government said that employers had to provide the best

sanitary conditions for workers, no crowded housing, social distancing.

When I started to visit SAWP workers before the peak of COVID-19 I

realized the employers were just keeping the same

things. PV:

No, it's exactly the same. We thought that there would be improvements

because the government said that employers had to provide the best

sanitary conditions for workers, no crowded housing, social distancing.

When I started to visit SAWP workers before the peak of COVID-19 I

realized the employers were just keeping the same

things.

I had a phone call from a worker in Mexico asking

me, how am I going to live, what is the housing, how is the employer

going to treat me now, so I decided to talk with his employer and they

just told me, well tell him that we're going to take care of him,

we have a trailer for him to live in, the trailer has the best water

and

electrical conditions but no, no, the government did not talk about

trailers, the government talked about having the workers in quarantine

in hotels or in other houses.

I talked to several employers and it was clear that they were not about

to take care of the workers. I think that is the reason the British

Columbia government decided to take

care of the 14-day quarantine in hotels near the Vancouver airport when

the workers arrive, before they were allowed to come to Kelowna,

because they realized that the employers were not respecting the rules.

WF: Are there fewer migrant workers this year?

PV:

There are fewer people from Mexico and from Jamaica, I know. The

majority of workers who come to BC are from Mexico, I think about 70 per cent,

and the rest are from Jamaica, and probably 5 per cent from Guatemala.

WF: What does RAMA do?

PV:

RAMA was founded ten years ago by Amy Cohen and Elise Hjalmarson and we

help migrant workers in many ways. For example, we provide English

classes, we organize soccer games and other social events. If they have

an emergency we take them to the doctor. We translate for them. If they

have problems with employers or managers

we also offer interpretation and translation services. What we want is

to socialize with them, to make them feel included in Canadian society

because all the farms here are far away from the city and the workers

are very isolated. We also make the people in the Okanagan aware of

their presence in the community, the role they play in food

production and their working conditions. We also provide legal

assistance.

WF: How are the workers recruited?

PV:

Since 1974 there is a memorandum of understanding between Mexico and

Canada. The employer has to fill out a Labour Market Impact Assessment

then this documentation goes to the labour office in Mexico and in

Mexico they have a big list of workers they provide the Canadian

employers. This is between the Mexican consulate in

Vancouver and the employers in BC. There's a lot of discrimination.

Employers don't want women so they don't select women from the list.

They also try to get the same workers year after year so new people

have little chance. Employers can also refuse to take a worker that has

been 'complicated,' complained to Worksafe BC or spoke out loud

about the working or living conditions. This means workers don't speak

out, even to the consulate, because they fear losing the work. This is

a kind of punishment.

Two days ago I talked with a worker who told me "two

years ago I had an accident and I seriously injured my back and then I

talked with the consulate. My employer took good care of me but the

consulate told the employer that I needed to get back to Mexico," so

even when the employer was worried about the worker the consulate

decided to take him to Mexico and once the worker was in Mexico the

consulate told the worker 'well you are in Mexico, you don't deserve

any medication, you don't deserve any treatment, your wife can take

care of you.' Then the consulate cancelled his application to work in

Canada for two years. Now he is here but he decided not to talk to

anyone about anything. He told me, if I have an accident I have to take

care of myself by myself and god help me.

WF: How has COVID-19 complicated matters?

PV:

Workers under the SAWP are forbidden to unionize and are denied basic

rights that Canadian workers have. There are many examples of poor

living conditions. Last year we visited one farm where the employer

housed 15 workers in a small room four metres square. One worker told

me that he has to walk about one kilometre to use the

washroom and he is not paid for the time it takes to go there and back.

He said the washroom hadn't been cleaned in one year. So COVID-19

complicates things because of the overcrowded houses, because of the

poor sanitation and because workers get respiratory and skin injuries

because they are constantly exposed to the use of pesticides and

irritants with no protection. What has changed is the fact that they

are more policed than they used to be because employers don't want

anyone to know about their conditions, so they are even more

isolated.

At one farm with about 100 workers the workers told us

"don't come here, don't approach us because if the employer sees us

talking with

any person not from the farm we are going to be punished with being put in

quarantine for two weeks without pay, so please don't come around. Don't

even call us frequently because if one of the managers knows that I am

talking to you I am going to be punished." As well, SAWP workers are

not eligible for citizenship or permanent resident status.

Farm workers are considered crucial to food production

in Canada because they are willing to do the dirty work, but they are

undesirable as permanent residents. One of my friends has been working

in Canada for 26 years, coming to Canada to work for seven to eight months

every year, then going back to Mexico but still she is undesirable as a

permanent

resident. This is not acceptable and RAMA supports the call for

permanent resident status for seasonal agricultural workers.

- Diane Johnston -

This year, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is estimated that

Quebec will only receive a maximum of 12,000 Mexican and Guatemalan

temporary foreign agricultural workers instead of the approximately

17,000 who came last year. To make up for the shortfall, huge pressure

is being exerted by some employers on those already here,

who are being asked to work 16-18 hour days. They're exhausted and even

though they may be told that they don't have to, "they're scared," says

Michel Pilon of the Quebec Migrant Agricultural Workers Help Network

(RATTMAQ).

This year, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is estimated that

Quebec will only receive a maximum of 12,000 Mexican and Guatemalan

temporary foreign agricultural workers instead of the approximately

17,000 who came last year. To make up for the shortfall, huge pressure

is being exerted by some employers on those already here,

who are being asked to work 16-18 hour days. They're exhausted and even

though they may be told that they don't have to, "they're scared," says

Michel Pilon of the Quebec Migrant Agricultural Workers Help Network

(RATTMAQ).

In April, the help line set up by the organization,

whose mission is to offer assistance to Quebec's temporary foreign

agricultural workers on issues relating to immigration, health,

education and francization, received close to two dozen telephone calls

from foreign workers overly-solicited by their employers to make up for

the slack. And

although all the complaints remain anonymous, they nonetheless testify

to the huge pressure being exerted on these workers by some employers

in Quebec's agri-food industry.

Unwarranted and unauthorized confinement measures are

also being taken against some of these workers by certain employers,

which only exacerbates the intolerable stress these workers are

experiencing.

Upon their arrival at the airport, RATTMAQ has been

handing out leaflets to these Mexican and Guatemalan temporary foreign

workers about COVID-19, the 14-day quarantine period they are to be

immediately placed under, along with information on their rights during

this period of the pandemic.

In April, RATTMAQ received over twenty calls regarding

disciplinary measures that had been taken against some workers for

having left the farm after their 14-day quarantine was over. For

example, one of these workers had decided to go out on his day off to

buy food. Although he had followed the required social distancing

measures, disciplinary action was taken against him because he had left

the farm. "Producers are saying they're afraid COVID-19 will make its

way to their farms, so they're controlling their movements. That's not

okay," RATTMAQ spokesperson Michel Pilon told the media.

Quebec's Union of Agricultural Producers notes in

one of its newsletters that following their quarantine, workers fall

under the same rules as everyone else when going outside. It adds that

they have the right to leave the farm if they so desire. The employer's

responsibility, it points out, is to ensure they are aware of the rules

when

going out, of social distancing and the risk of infection.

Preventing them from going off-site, it warns, would contravene

Quebec's Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

The United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW Quebec),

which represents some of these workers, has also been informed that

some workers have been prohibited from leaving their employer's

grounds. UFCW Quebec representative Julio Lara was forced to intervene

with one employer, after some workers were suspended for having left

their employer's grounds.

Just

like the many other temporary foreign migrants, including refugee

claimants and international students working in Quebec's health care

sector, slaughterhouses, warehouses and in our fields, these workers'

rights are being grossly violated. Not only do they face the denial of

their rights by their employer, the Quebec and the federal

government also bear huge responsibility for their living and working

conditions and continue to turn a blind eye to their fate. Though they

are often enticed here with the possibility of being able to

settle permanently, the decks continue to be stacked against them

through constant arbitary changes to immigration policy by

both the Quebec and federal governments. Just

like the many other temporary foreign migrants, including refugee

claimants and international students working in Quebec's health care

sector, slaughterhouses, warehouses and in our fields, these workers'

rights are being grossly violated. Not only do they face the denial of

their rights by their employer, the Quebec and the federal

government also bear huge responsibility for their living and working

conditions and continue to turn a blind eye to their fate. Though they

are often enticed here with the possibility of being able to

settle permanently, the decks continue to be stacked against them

through constant arbitary changes to immigration policy by

both the Quebec and federal governments.

Regarding the insufferable stress they are placed under,

one example is the letter dated April 1, 2020, signed by federal Health

Minister Patty Hajdu and Employment Minister Carla Qualtrough, which

informs employers that "It is important that you know that penalties of

up to $750,000 can be levied against a temporary foreign worker for

non-compliance with an Emergency Order made under the Quarantine Act."[1]

On April 22, the federal government announced it was

removing the restriction allowing international students to work a

maximum of 20 hours per week while classes are in session, "provided

they are working in an essential service or function, such as health

care, critical infrastructure, or the supply of food or other critical

goods." This

measure significantly increases the risk of them contracting COVID-19.

In Quebec, the new measures brought in by the Legault

government through its reformed Quebec Experience Program (PEQ), which

came into force at the end of June, will increasingly prevent

many low-skilled temporary workers and international students from

being able to permanently settle in Quebec.

Quebeckers and Canadians from all walks of life continue

to rally to the cause of these and other essential workers for the full

recognition of their rights, including permanent residency upon

arrival. The jobs these workers fill are not temporary, they are

recurring, with no takers in the Quebec and Canadian domestic market,

because of the

conditions of indentured labour attached to them.

The workers who fill these recurring jobs year in, year

out, must be given permanent residency upon arrival if they so desire,

as must all essential workers living here whose status has not been

regularized. Their rights as human beings, as well as workers, to decent

and dignified working and living conditions must be recognized now. It

is only

by working together and organizing in defence of the rights of all that

we will succeed, shoulder to shoulder, in turning their situation

around. If they are good enough to work, then they are certainly good enough to stay and

deserve the same rights as other Quebec workers. As essential workers,

they are the ones providing care

and ensuring that food is put on our tables. By speaking out and

organizing with them in defence of their rights, we are also fighting

for the recognition and guarantee of our own.

Note

1. TML Weekly, May 2, 2020, Temporary Foreign Workers Merit Permanent Residency, Not Threats! - Diane Johnston

(To access articles individually click on the black headline.)

PDF

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: office@cpcml.ca

|