|

October 7, 2017 - No. 31 Homage to Ernesto

Che Guevara

Reminiscences Homage to Ernesto Che Guevara on the 50th Anniversary of His Assassination Today we pay deepest homage to Ernesto Che Guevara, the indomitable revolutionary fighter and proletarian internationalist whose legacy inspires millions. Hailing from Argentina, a doctor who wished more than anything to contribute to ending the suffering of the peoples of Latin America and the world, he joined without hesitation Comrade Fidel and the Cuban revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra to liberate Cuba. He earned the honour of Heroic Guerrilla for his feats in battle which contributed decisively to the defeat of the cruel Batista dictatorship in 1959 and the subsequent triumph of the Revolution. Che achieved this by devoting himself to making sure the economic base was established which would secure the well-being of the Cuban people, while also contributing to making sure everyone in Cuba was literate and that viable means of communication were established. He is known for promoting volunteer labour as a means of transforming the consciousness of human beings to ensure their society always fulfills its social responsibilities. He was the finest example of the modern human person, for whom principles guided his every action. His actions exuded social love and concern for his fellow human beings.

His internationalism and Cuba's internationalism are synonymous. They are self-sacrificing; devoid of arrogance or narrow sentiments which put self-interest first. Che Guevara was imbued to his very core with the desire to engage the peoples all over the world in the fight for their freedom, holding high the banner of anti-imperialist and anti-colonial struggle in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. Ernesto Che Guevara died a heroic death on the

battlefield of

Bolivia 50 years ago and the world mourns his loss as if it

were only yesterday that he joined the columns of communist and

revolutionary martyrs. Today, the people of Quebec and Canada,

together with the heroic Cuban people and the revolutionary

peoples throughout the world, commemorate the 50th

anniversary of his assassination at the hands of the despised

U.S. CIA by renewing our pledge to defend the Cuban Revolution of which

Fidel, Che, Raúl, Camilo, Vilma, Heidi, Tania and their comrades were

the architects, and all the revolutionary Cuban guerrilla fighters and

people who are one with them. We renew our pledge to defend the

right of all nations to self-determination which includes as its

integral part, as Che taught us, the crucial right to

self-defence.

Hasta la Victoria Siempre!

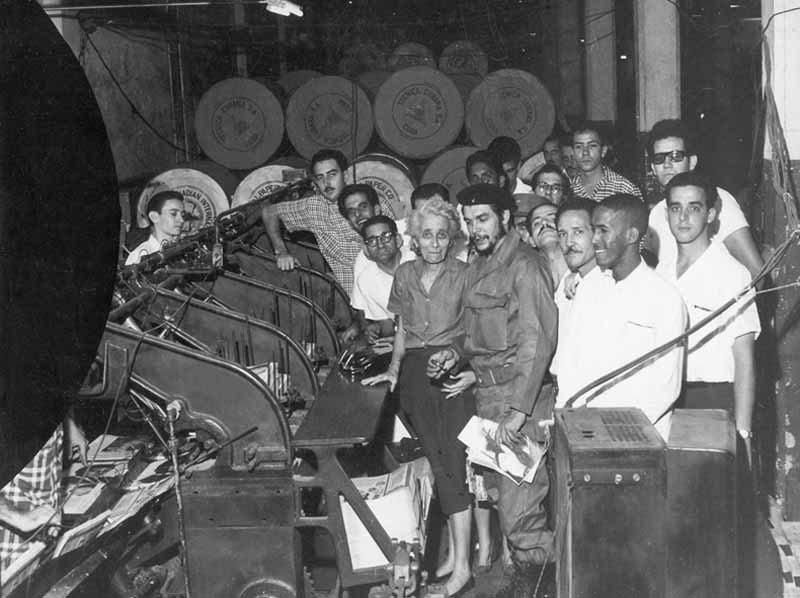

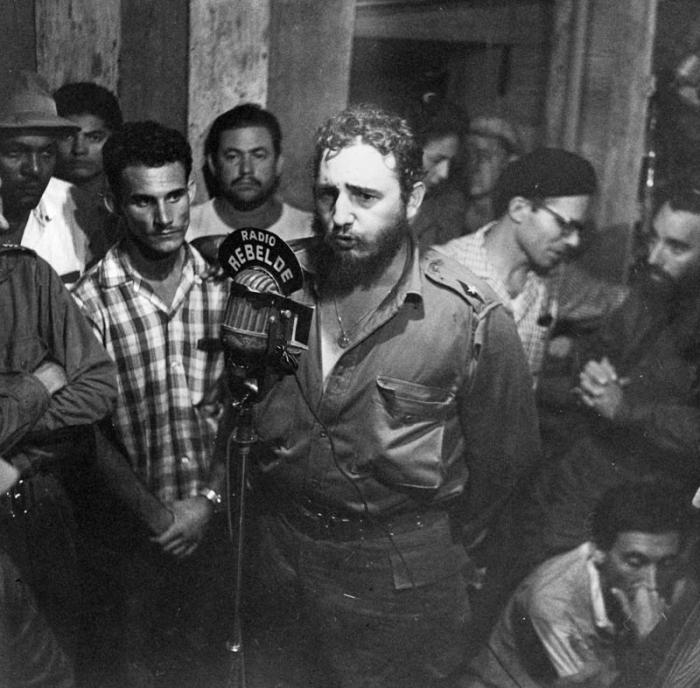

Reminiscences Che the JournalistThese days we are commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Commander Ernesto Che Guevara after he was wounded in combat in Bolivia in October 1967. We recall the profound but still little known footprint he left in journalism in our America, something that is eclipsed by the whole of his great work which, as Fidel Castro put it, we should celebrate with glory, not by mourning. Che was a journalist like Fidel, like José Martí, not only to generate more and more love for revolutionary ideas, but also to unleash the excellence that burned within them; their virtues as communicators. It is virtually unknown that the young Guevara was not only the correspondent in Mexico for Agencia Latina (AL) to cover the Pan American Games of March 12-26, 1955, almost two years before the Granma, but also that Ernesto Guevara wrote the stories that were published and credited to AL and took the photos, as Severino Rosell told the commander William Gálvez. "El Guajiro" Rosell and Fernando Margolles used to develop and print those photos, as Che would take them to work with him [so they could] earn something at the Argentine agency. By then his life was solidly linked to that of Fidel and Raúl Castro and the revolutionaries of the island. In 1957 Che was the creator, with Fidel, of Radio Rebelde and the important initiatives it undertook. Without them, the world of the 1950s would have known practically nothing of what was happening in the Sierra Maestra. Both of them devoted no small amount of their time and talent to patiently passing on information through their broadcasts about how those dozen guerrillas who managed to regroup in Cinco Palmas in 1956 were making ceaseless progress after what Che rightly described as a shipwreck rather than a disembarkation. Radio Rebelde

In the Sierra Maestra, Che was not only one of the most outstanding guerrillas, but also their chronicler and something even more important: [He was,] with Fidel, the architect of the creation and operation of the Radio Rebelde station which transmitted the daily actions of the guerrillas to the ears and minds of the Cuban people and the peoples of Latin America. That struggle was instilled in the hearts of everyone, "always mindful of the fundamental principle that truth and the facts, in the long run, end up favouring the peoples."[1] Daily, through the voices of Violeta Casals, Jorge Enrique Mendoza, Orestes Valera and Ricardo Martínez, news of the guerrilla struggle from Radio Rebelde became the most important and serious source of information. Radio Rebelde made a fool of the dictator Fulgencio Batista who right up to December 31, 1958, informed UPI [United Press International] that they had wiped out the rebel army. That is why the revolutionaries in Madrid agreed, on that last night of 1958, that they should return to combat however they could, to supply those who had courageously come to Santa Clara with Che and Camilo. At six in the morning of that 1st of January they could not believe Batista had been defeated. After the victory and playing a decisive role in the invasion with Camilo Cienfuegos, like Antonio Maceo in 1896, Che continued writing in several organs like Verde Olivo and Combate. But his untiring journalism and political work did not

end

there. Anyone who wanted to get an idea of the dimension of his

informational work should look at the seven volumes of about 500

pages each of the monumental work Che

in

the

Cuban

Revolution

compiled by his collaborator, Orlando Borrego Díaz.

New Latin American Agency

Che and Fidel were the real creators of Prensa Latina, a Latin American information agency to help break the monopoly the famous "P"s (AP and UPI) had in Latin America at the time. "In mid-January (1959) Che tells his mother he is awaiting the arrival of Jorge Masetti, to whom they are going to entrust the creation of an international news agency."[2] It is not well known that the funds to create it were put up by the 26th of July Movement. And it was Che who delivered them in those difficult beginnings. Perhaps the heroic guerrilla recalled how much he used to suffer to be able to collect his salary as a correspondent for the Argentine agency on that Ides of March, 1959. With great effort and imagination, Prensa Latina has managed to sustain itself ever since.[3]

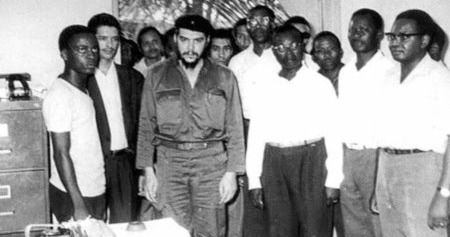

Notes1. Che in the Cuban Revolution, Volume VII. Orlando Borrego, Editorial José Marti, 2017, p.89. 2. Celia, Che's mother. Julia Constela, Editorial Sudamericana. Buenos Aires, 2004, p.187. 3. From Semanario Orbe. Gabriel Molina Franchossi founded the Union of Cuban Journalists (UPEC), and was also a founder and one of the editors for the newspapers Granma, Combate and the weekly Opina. He is also the founder of Agencia Prensa Latina, founded on the initiative of Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara, with the specific aim to spread the truth in Latin America. Molina was vice-president of the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television (ICRT), responsible for national, international and political information, after which he occupied the position of director of Granma International for 29 years, a weekly paper published in seven languages. In 2000 he received the National Journalism Lifetime Achievement Award. (Prensa Latina, May 14, 2017. Photos: Cuban Office of Historic Affairs) Che in 1959

|

|

|

Later, I would learn more details about our mission; the primary objective of diversifying our trade by placing most of our sugar production in those markets and replacing the majority of our imports with products from those places.

Once in the USSR, an emergency meeting took place in Moscow that included almost all of the foreign ministers of the socialist countries. In the meeting, Commander Guevara explained the serious situation facing the Cuban Revolution given the imperialist aggression, and as the main theme, the need to place four million tons of sugar in those markets, at a price of four cents per pound. This price was higher than the rate on the New York Stock Exchange at the time.

He also said it was necessary for Cuba to buy its essential products from those countries.

You should remember that at the time, Cuba did not yet have a Ministry of Foreign Trade, and we had very little information, and even less experience, in that area. All we had were solid political arguments and a letter signed by our prime minister, Commander Fidel Castro, which had the above mentioned request, and its bearer was Commander Guevara.

What were the agreements reached?

As a result of those

negotiations, the USSR promised

to buy

2.7 million tons of sugar; China, one million tons; and the other

socialist countries, 300,000 tons.

In addition, Korea, Vietnam and Mongolia bought symbolic quantities as an expression of support and solidarity with the socialist countries.

In Moscow, a multilateral agreement on payments was also signed.

With the goal of reaching trade agreements that included lists of the products to be bought and sold, payment agreements and credit agreements, the delegation led by Che also visited Czechoslovakia, China, Korea and the Federal Republic of Germany.

During his stay in China, and to save time, Che decided that he would visit the Democratic Republic of Korea, and had me lead a small group to Vietnam and Mongolia, countries with which we also established diplomatic relations at the time.

At the end of his stay in Berlin, Che had to return to Cuba, informing us that he would make a short stop in Budapest and that the delegation I was leading from then on should travel to Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania.

Was there already talk of the need to change Cuba's trade structure?

After arriving in Cuba, Commander Guevara appeared on television on January 6, 1961, to report on the signing of the agreements with the socialist countries:

"It was an extremely difficult task, a difficult task, because we have had to change the structure of our trade in just a few months. From the end of 1959, exactly one year ago, Cuba has passed from being a country with a totally colonial structure, with domestic and foreign trade systems completely dominated by the large import companies dependent on monopoly capital, to being -- in 10 months, as of October, when the cycle definitively ends -- a country where the state holds a complete monopoly over foreign trade, and also a large part of domestic trade."

He also referred to additional difficulties that we were facing, given that in those countries, the decimal metric system was used, while we continued to use the colonial practice of weighing in pounds and measuring in yards, with different systems for measuring pressure or a simple pipe fitting.

Electrical equipment in Cuba uses 60 cycles, while in the socialist countries, it was 50 cycles per second.

In short, we were facing all types of difficulties, but with the determination to overcome them and triumph over them in face of the dilemma created for us by the imperialist aggression.

Interesting anecdotes emerged out of these initial experiences.

For example, in China, when evaluating the list of products to be traded, there was a difference of $3 million favoring the Chinese side.

Before signing the final protocol, the Chinese prime minister at the time, Chou En-lai, told Che that China should not appear to be receiving more in products than what it was exporting to Cuba.

So it was decided to have a line of $3 million in arts and crafts exports, given that at the time, we could not find any other products that met our needs.

It was out of that protocol contingent of Chinese arts and crafts that lots of stories circulated in Havana about the large volume of Chinese walking sticks and umbrellas being sold in our stores.

Actually, the Chinese sent us valuable craftwork that I am sure exceeded the value previously mentioned.

I always believed that neither they nor we really valued those wonderful things.

On the contrary, certain foreigners who were living in Cuba temporarily did take advantage of the situation, enriching themselves through the illegal sale of those art treasures.

Another source of anecdotes and jokes was the snow removers. I think that these actually had a basis in truth, in machines that were the same or similar and were purchased to be tried out in our mining industry.

I will never forget the look of amazement on the face of the Soviet translator who, in reading the list of things we needed, did not know what to say when a typing error led him to read the need for thousands of "monkey lips" (bembas de mono) instead of "hand pumps" (bombas de mano).

We joked amongst ourselves about the decision by Commander Guevara to buy all the canned meat we could, and also all the machine tools that we could.

A few months later, we would realize how correct those decisions were when, mobilized to occupy trenches or as a volunteer in cutting sugar cane, I thought the Russian meat tasted glorious, after having made so many faces when we first tried the samples they had given us.

We had the same internal satisfaction of knowing that the problem created by the blockade of a shortage of spare parts could be solved through the machine tools we had bought, which a comrade on the delegation had commented on by going so far as to say that on the next Day of the Three Kings [January 6 -- TML ed.], we would have to do propaganda among the country's parents so they would give each child the present of a machine tool.

Personally, I have unforgettable memories of those days together with a man as peerless as Che.

I had the opportunity to meet prominent individuals like Mao Zedong and Chou En-lai, Nikita Krushchev, Walter Ulbricht, Pham Van Dong and other outstanding leaders of the socialist camp.

But it is with special affection and admiration that I remember one agreeable and helpful young woman who helped us as a German translator in the Federal Republic of Germany, Tamara Bunke Bider, who years later would go down in history as Tania the guerrilla fighter.

On February 23, 1961, the Ministry of Foreign Trade was created, with Alberto Mora appointed as its minister.

What problems were created by those changes in foreign trade, and what role did Commander Guevara play in resolving them?

Some time after returning from the trip to the socialist countries, I was appointed deputy minister of foreign trade.

During those early years of organizing and readapting our foreign trade, and despite having multiple responsibilities, Commander Guevara played an exceptional role in attending to and developing it.

During those years, Che referred publicly to foreign trade activity, sometimes to refute those who, like the [newspaper] Diario de la Marina, maliciously criticized the first agreements with the Soviet Union. He did that during a talk he gave at the University of Havana on March 2, 1960, and days later, on March 20, 1960, as part of the inaugural lecture of the TV program "The People's University."

He also referred to the main difficulties we were facing at the time in taking on these tasks, such as during the speech he gave at a planning seminar in Algeria on July 13, 1963, where he said:

"Our foreign trade had changed completely in location. From 75% with the United States, it went to 75-80% with the socialist countries. A beneficial change for us in every respect, political and social, but in the economic respect, it required a large amount of organization.

"Hundreds of specialized importers used to make their requests to the United States by telephone, and the next day they would arrive by ferry, direct from Miami to Havana. There were no warehouses or foresight of any kind.

"That whole apparatus, without those technicians, enemies of the government, had to be established in what was first the Foreign Trade Bank of Cuba and later the Ministry of Foreign Trade, and centralize all of these purchases there with inexperienced people, to do them now, not one day away by telephone, but two months away, in long talks. And at the same time, raw materials that had a different name. And even more: if you all go today to a factory in this country and want to know what kind of steel is used for a given spare part, you will find that it has a number in a catalog, the SKF-27, for example. The SKF-27 in that company's sales catalog corresponds to a particular component; how could that be requested in the socialist countries? We had to do analyses of steel, sometimes machine fabricate one or two particular parts. Almost impossible. We had to import the machines here in Cuba, with a shortage of highly-qualified technicians."

Those were Cuba's everyday problems -- and still are.

Was he pleased with the course of those trade relations?

Che foresaw and warned of the difficulties and obstacles that, in our own experience of trade relations with certain socialist countries, led to the latter following capitalist patterns in the conduct of their relations with underdeveloped countries.

So, in a speech he gave in Algiers on February 24, 1965, at the second Afro-Asian Economic Solidarity Seminar, he said:

"Socialism cannot exist unless there is a change in people's consciousness, creating a new, fraternal attitude toward humanity, both individually, within the society in which socialism is being or has been built, and in relation to the world, with respect to all of the nations that suffer imperialist oppression."

Note

1. Jaime Barrios, a Chilean, was killed on September 11, 1973 at La Moneda Palace.

(June 2008. Photo: Centro de Estudios

Che Guevara )

Che's Passion for the Nickel Industry

Comandante Ernesto Guevara took a personal interest in developing the industry, dedicating his keen strategic vision and organizing capacity to the effort.

|

|

HOLGUÍN.– Avoiding interviews was a constant in engineer Demetrio Presilla López' life. But in the few that he agreed to regarding his role in the resumption of national nickel production, he never failed to mention that day in December, 1960, when Comandante Ernesto Guevara, then head of the National Institute for Agrarian Reform's (INRA) Industrialization Department, asked him to get into operation a recently built plant in Moa, abandoned by a U.S. company on April 9 of the same year, as part of the economic measures adopted by the U.S. government to stifle the Cuban Revolution.

Che spoke of a gradual process, but was clear on the need to restart the industry, as the Hero of Labor of the Republic of Cuba recalled, who passed away in Moa in March 2006.

The long-ago meeting had been promoted by the guerrilla commander. Presilla noted that during their conversation, he made comments and asked questions about the difficulties that could arise in marketing the final product, to which Che replied that Presilla would be in charge of getting the plant into operation, and that he would be responsible for the supplies needed for production and the sale of nickel.

Such confidence assured those gathered that there would be no backtracking in the task entrusted to them. Che was convinced of the possibility of success, and dedicated his keen strategic vision and the organizing capacity that distinguished him as a guerrilla, to the efforts.

Tireless and Foresighted

Che was also tireless. According to the chronology in which journalist Camilo Velasco describes the relationship between Che and the nickel industry, he also met in mid-December, 1960, in Havana, with a group of 17 engineers and technicians who had participated together with U.S. specialists in the fitting and testing of the inactive Moa plant, taken over by the INRA on August 5 of that year, when it became known as the Comandante Pedro Sotto Alba plant.

In fact, throughout 1960, the INRA was very active in the recovery of nickel production. On August 19, the institute executed the official takeover of the Cayo del Medio mining company, which exploited the Cayo Guan deposits and other mines.

In addition, on October 24, Resolution No. 16 of the Cuban Institute of Mining established the nationalization of the Nicaro nickel industry, which immediately received the name of Comandante René Ramos Latour.

On January 6, 1961, the traditional celebrations for Día de los Reyes Magos (Three Kings' Day) were held. They were accompanied, fittingly perhaps, by an appearance by Che on Cuban television. He reported the signing of agreements with various socialist countries, and the commitment of the Soviet Union to send specialists to assist with the start-up of the nickel plant.

Previously, in December 1960, a delegation from the Soviet Union had visited Moa to learn about the plant's technology.

Completely immersed in this mission, at the end of April, 1961, in a conference at the Popular University, Comandante Ernesto Guevara, then Minister of Industries (he had been appointed to the position on February 2 that year) detailed that the basic products of Cuban mining were iron, nickel, and copper. He also noted that there were cobalt and chromite deposits. He noted that some of the greatest potential resources were laterite deposits located in the north of the eastern region of the island, in the areas of Nicaro, Moa, and Baracoa.

As for the Comandante Pedro Sotto Alba plant, on stating that it would probably be up and running in a short period, Che asserted that this should be regarded an accomplishment of the Revolutionary Government, as it had previously been inoperative.

As one reviews what was done in 1961, the admiration for Che's efforts inevitably grows. In May, in Havana, he received a delegation headed by the Vice Minister of Economy of the USSR, who explored the negotiation of future agreements for the purchase of Cuban nickel. In August, during the first national production meeting of the sector that he led, Che stated that the René Ramos Latour plant, in Nicaro, had produced 7,620 tons, which represented a slight increase compared to the same period the previous year.

In October, Che made public the decision to build a future steelworks in Oriente province that would use iron and nickel from the Moa and Nicaro areas as its raw materials.

Later stages were equally dynamic and creative. It is logical to suppose that Che's views were taken into account regarding other essential steps undertaken by the Revolutionary Government, including the creation, in July 1963, of the Coordinating Center for the Northern Oriente Development Plan (Plan Norte), whose fundamental objective was to boost the nickel industry.

Physical Presence of Che in Nickel Production Facilities

Following the habit of leaders of the Revolution to personally visit areas undergoing transformations, to verify the developments themselves, Comandante Ernesto Che Guevara toured the areas and facilities related to nickel production and made detailed analyzes of the sector.

Like Camilo Velasco, journalist and historian María Julia Guerra notes in her chronology of Che's visits to the province of Holguín, that he visited the locality of Nicaro for the first time on January 20, 1961. At that time, he toured the nickel plant and spoke with workers.

He likewise toured the local community, and in the central park he spoke to residents regarding the need to work to create the country's wealth.

A little more than a year later, Che repeated this tour of the industry, to which he would return several times during 1963. During one of these visits, he participated in an extraordinary management board meeting of the Consolidated Nickel Company.

Regarding Che's first exchange with the René Ramos Latour plant workers, Manuel Galbán Sopeña, one of those deeply involved in the recovery of domestic nickel production, reported that the Comandante arrived without any prior warning, aboard a jeep. "He observed the classes on processes and metallurgical balance that I taught to a group of compañeros, asked several questions and then said goodbye, recommending we continue like that."

Che's initial visit to the Moa region occurred on May 26, 1961. He was accompanied by Comandante Raúl Castro Ruz, Aleida March, and Vilma Espín. They visited the Pedro Sotto Alba plant and the Cayo Guan mine. On noting the way in which the workers of the chromite mine lived, Che expressed the need to improve their living conditions by building decent housing.

In January, 1963, as well as visiting Nicaro, Che toured Moa. He held meetings with leaders of revolutionary organizations from both localities and administrative and union cadre in the René Ramos Latour and Pedro Sotto Alba plants. He also toured Punta Gorda and the Cayo Guan mine again.

Che returned to Moa in September, 1964, to converse with chromite miners and verify the operations of the Comandante Pedro Sotto Alba plant. There he assured Juan Rodríguez Guerrero, general secretary of the union bureau, that on his next trip he would meet with the workers.

He fulfilled that promise at the end of November 1964. It was his last visit to the region. He was accompanied by José Cardona Hoyos, leader of the Communist Party of Colombia, among others. In the Ciro Redondo cinema, Che presided over the workers assembly of the Comandante Pedro Sotto Alba company. During his speech, he admitted that this industry was one of his most beloved.

A Right Recognized by the People

On January 11, 1984, to the north of the mineral deposit of Punta Gorda, in Moa, the Comandante Ernesto Che Guevara plant was put into operation. Designed to produce nickel and cobalt, which is internationally recognized, the plant was named to honor the efforts and talent demonstrated by the heroic guerrilla in leading the recovery process of the national nickel industry. His audacity was decisive to the materialization of the Development Plan of the northern Oriente coast.

Fidel and the highest authorities of the Party and the government had promised that the first great installation of this type to be built by the Revolution with the help of the socialist camp, especially the USSR, could only be named as such. And the Cuban people agreed.

(Granma International, August 23, 2017. Photo: A. Korda)

Alongside Che During the October Crisis

Oscar Valdés Buergo shows a photo of the Los Portales Cave,

where Che established his

command during the October Crisis.

In his command headquarters, Comandante Ernesto Guevara analyzed with various officers the composition of the enemy force threatening to attack the country.

Lieutenant Luis González Pardo, head of the information section, read data on the 82nd Airborne Division of the United States Army, which would reportedly be responsible for the attacks.

After mentioning the enormous amount of aircraft, Luis commented: "Comandante, they are going to cover our sky."

Che, however, was not fazed. Following the abrupt defeat of the dictatorship and the mercenary attack on Playa Girón, he had no doubts about the courage of the Cuban people, thus he assertively responded to his intelligence officer: "Even better, kid, we'll fight in the shadows."

Recounting the anecdote is Oscar Valdés Buergo, then adjunct sergeant to the military chief of Pinar del Río, and therefore a man close to the Heroic Guerrilla on the occasions when he assumed command of the province, during the invasion of Playa Girón and the October Crisis (Cuban Missile Crisis).

Supported by a folder full of notes, newspaper clippings, sketches and photographs, the veteran combatant of the clandestine struggle in Vueltabajo speaks with nostalgia of those "whirlwind days" in which he had the opportunity to work alongside Che.

Now aged 80, Valdés remembers him clearly -- in his fatigues, a pistol at his waist, and his black beret with a star.

"During Girón, the shot that escaped him and injured his face made his presence very brief, but during the October Crisis he stayed with us for several weeks, leading the province," Oscar recalls.

"At that time, Che established his command in Cueva de los Portales (a cave in the municipality of La Palma). He would leave at dawn almost every day to tour the territory and return at night."

Among the anecdotes that speak for the legendary guerrilla's personality, Oscar notes that since they never knew what time Che would return, it was proposed that they place a wood stove inside the cave, to keep food warm for all of those who worked late into the night, as the unit's main kitchen was located at some distance.

"Che at first did not agree, because he thought they were doing it with the intention of preparing a better meal for him than the rest of the troop, and although he finally agreed, when he walked around he always checked with the soldiers that everyone had been served the same."

Regarding those tense days, in which the world was on the verge of a nuclear conflict, Oscar recalls that on one occasion Che arrived very annoyed, as a group of militia and soldiers who were digging trenches had asked him how long the exercise would last.

"That same day he ordered the principal leaders to go and update them, man to man, regarding the situation of great danger in the country.

"On October 26, after hearing the Comandante en Jefe say that any aircraft that violated our airspace would be shot down, he ordered the air defense to be reinforced.

"In addition, he gave the order to disassemble a 12.7 millimeter machine gun, and with ropes and the help of a group of campesinos from the area, they carried it up piece by piece to the top of the hill and positioned it there."

A radio antenna was also placed up there, in order to tune into foreign stations, and several compañeros who spoke other languages listened to them constantly, so that they could keep him informed.

"Once, in a meeting, he asked the unit heads, who listened to foreign radio stations. There was total silence, and only First Lieutenant Narciso Ceballos, head of the Guane division, raised his hand and said, 'I do, Comandante, because they told me you did it.'

"People thought that Che would reprimand him, but he congratulated him, and he told the others that they had to be informed and know the enemy."

Although Che was a very strict man, Oscar says he spoke very softly and very politely. "During the time he was the chief political and military leader of Pinar del Río, he toured the entire province, including the Guanahacabibes peninsula, but above all the north coast, near the capital of the country.

"In the cave, leaders of units and the principal entities of the province went to see him and to check in. The hustle and bustle was tremendous," he recalls.

However, Oscar explains that there was also free time during the evening, in which Che would go out and talk to people, read, play a game of chess or stop to watch others do so, and he would comment aloud when there was a bad move, to irritate them.

"One night I was reading a book about Latinos' lives in New York City, and he stopped by my side and said, 'Lend it to me when you're done.'

"A little later he came back and said, 'I've come to get the request.' He took the book and I never saw it again."

The outcome of the October Crisis is known. Oscar states that after returning from a meeting in Havana, Che met with the political and military authorities of the province, and explained that behind Cuba's back, the Soviet Union had reached an agreement with the United States to withdraw the nuclear missiles from the country, and he had very strong words to say regarding this solution.

Today, 55 years later, Oscar notes that having had the opportunity to be close to the Heroic Guerrilla at a crucial moment in the history of the Revolution, was one of the most extraordinary experiences of his life.

"I am honored by the confidence he had in me for this important mission," he says.

"Che was a man who always led by example, and he did not order us to do anything that he was not willing and able to do himself.

"People liked talking to him. We admired him a lot. It

was a

very big thing for all of us."

(Granma, September 18, 2017. Photos:

R.S. Rivas, Granma)

Che As I Knew Him (Extract)

Che is received at the international airport in Algiers by Algerian

Prime

Minister Ahmed Ben Bella, July 3, 1963, for the celebration of the

first

anniversary

of Algerian independence.

[...]

I first met Ernesto "Che" Guevara in the autumn of 1962,

on the eve of

the international crisis around the missile affair and the United

States blockade of Cuba.[1]

Algeria had just achieved independence and formed its first government.

As head of that government, I was due to attend the September 1962

session of the United Nations in New York at which the Algerian flag

would be raised for the first time over the UN building, a ceremony

marking the victory of our national liberation struggle and Algeria's

entry into the concert of free nations.

Visits to Washington and Havana

The National Liberation Front's political bureau had decided that the trip to the United Nations should be followed by a visit to Cuba. More than just a visit, it was intended as an act of faith demonstrating our political commitment. Algeria wished to emphasize publicly its total solidarity with the Cuban revolution, especially at this difficult moment in its history.

I was invited to the White House on the morning of October 15, 1962, and had a frank and heated discussion about Cuba with the president, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. I asked him point blank: "Are you heading towards a confrontation with Cuba?" His reply left no doubt about his real intentions. "No," he said, "if there are no Soviet missiles. Yes, if there are." Kennedy tried hard to dissuade me from flying to Cuba direct from New York. He even suggested that the Cuban military aircraft that was to fly me to Havana might be attacked by Cuban opposition forces based in Miami. To these thinly veiled threats I retorted that I was a fellah who could not be intimidated by harkis, whether Algerian or Cuban.[2]

|

|

We stayed and talked for hours and hours. I naturally conveyed to the Cuban leaders the impression I had received from my conversation with President Kennedy. At the end of an impassioned discussion, around tables which we had pushed together end-to-end, we realized that we had practically exhausted the questions on the agenda. There was no point in a further meeting at party headquarters, and by mutual consent we moved straight on to the program of visits prepared for us across the country.

This anecdote gives an idea of the total lack of formality that, from the very beginning, was the norm for the relations uniting the Cuban and Algerian revolutions and of my personal relations with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

Cuban Troops Aid Algerian Revolution

The solidarity between us was spectacularly confirmed in October 1963, when the Tindouf campaign presented the first serious threat to the Algerian revolution.[3] Our young army, fresh from a war of liberation, had no air cover (since we didn't have a single plane) or armoured transport. It was attacked by the Moroccan armed forces on the terrain that was most unfavourable to it, where it was unable to use the only tactics it knew and had tried and tested in the liberation struggle, namely guerrilla warfare.

The vast barren expanses of desert were far from the mountains of Aures, Djurdjura, the Collo peninsula or Tlemcen, which had been its natural milieu and whose every resource and secret were familiar to it. Our enemies had decided that the momentum of Algerian revolution had to be broken before it grew too strong and carried everything in its wake.

The Egyptian president, Abdel Nasser, quickly provided us with the air cover we lacked, and Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Raúl Castro, and the other Cuban leaders sent us a battalion of 22 tanks and several hundred troops. They were deployed at Bedeau, south of Sidi Bel Abbes, where I inspected them, and were ready to enter into combat if the desert war continued. The tanks were fitted with infrared equipment that allowed them to be used at night. They had been delivered to Cuba by the Soviet Union on the express condition that they were not to be made available to third countries, even communist countries such as Bulgaria, in any circumstances. Despite these restrictions from Moscow, the Cubans defied all the taboos and sent their tanks to the assistance of the endangered Algerian revolution without a moment's hesitation.

The United States was clearly behind the Tindouf campaign. We knew that the helicopters transporting the Moroccan troops were piloted by Americans. The same considerations of international solidarity subsequently led the Cubans to intervene on the other side of the Atlantic, in Angola, and elsewhere.

The circumstances surrounding the arrival of the tank battalion are worth recalling since they illustrate better than any commentary the nature of our special relations with Cuba.

When I visited Cuba in 1962, Fidel Castro made a point of honouring his country's pledge to give us two billion old French francs worth of aid.[4] Because of Cuba's economic situation, the aid was to be provided in sugar rather than in currency. I objected, arguing that Cuba needed her sugar at that time more than we did, he would not take no for an answer.

About a year after our discussion, a ship flying the Cuban flag docked in the port of Oran. Along with the promised cargo of sugar, we were surprised to discover two dozen tanks and hundreds of Cuban soldiers sent to help us. A brief note from Raúl Castro, scribbled on a page torn out of an exercise book, announced this act of solidarity.

Che's Internationalist Work in Africa

Che Guevara was acutely aware of the countless restrictions that hinder and weaken genuine revolutionary action -- and indeed of the limits on any experiment, however revolutionary -- as soon as it confronts directly or indirectly the implacable rules of the market and the huckster mentality. He denounced them publicly at the Afro-Asian Conference held in Algiers in February 1965.[5] Moreover, the painful terms on which the affair of the missiles installed in Cuba had been concluded, and the agreement between the Soviet Union and the United States, had left a bitter taste. I myself exchanged very tough words on the matter with the Soviet ambassador in Algiers. All of this, together with the situation prevailing in Africa, which seemed to have enormous revolutionary potential, led Che to the conclusion that Africa was imperialism's weak link. It was to Africa that he now decided to devote his efforts.

I tried to point out that perhaps this was not the best way to help advance the revolutionary maturity that was developing on our continent. An armed revolution can and must find foreign support, but it first has to create the internal resources on which to base its struggle. But Che Guevara insisted that his own commitment must be total and required his physical presence. He made several trips to Cabinda (Angola) and Congo-Brazzaville.

|

|

He refused my offer of a private plane to help disguise his movements, so I instructed Algerian ambassadors throughout the region to provide him with every assistance. Whenever he returned from sub-Saharan Africa, we spent long hours exchanging ideas. Each time he came back impressed by the fabulous cultural riches of the African continent but dissatisfied with his relations with the Marxist parties of the countries he had visited and irritated by their approach. His experience in Cabinda and subsequent contacts with the guerrilla struggle around Stanleyville were particularly disappointing.[6]

Meanwhile, parallel to Che's activity, we were pursuing another course of action to save the armed revolution in western Zaire. In agreement with Nyerere, Nasser, Modibo Keita, N'Krumah, Kenyata and Sekou Touré,[7] Algeria contributed by airlifting arms via Egypt, while Uganda and Mali supplied military cadres. The rescue plan had been conceived at a meeting in Cairo convened on my initiative. We were beginning to implement it when we received a desperate cry for help from the leaders of the armed struggle. Despite our efforts, we were too late and the revolution was drowned in blood by the assassins of Patrice Lumumba.

During one of his visits to Algiers, Che Guevara informed me of a request from Fidel. Since Cuba was under close surveillance, there was no real chance of organizing the supply of arms and military cadres trained in Cuba to other Latin American countries. Could Algeria take over? Distance was no great handicap. On the contrary, it could work in favor of the secrecy vital for the success of such a large-scale operation.

I agreed, of course, without hesitation. We immediately began to establish organizational structures, placed under the direct control of Che Guevara, to host Latin American revolutionary movements. Soon representatives of all these movements moved to Algiers, where I met them many times together with Che.

Their combined headquarters were set up in the hills overlooking Algiers in a large villa surrounded by gardens, which we had assigned to them because of its symbolic importance. The name of the Villa Susini has gone down in history. During the national liberation struggle it was used as a torture center where many men and women of the resistance met their death.

One day Che Guevara said to me, "Ahmed, we've just been struck a serious blow. A group of men trained at the Villa Susini have been arrested at the border between such and such countries (I can't remember the names) and I'm afraid they may talk under torture." He was very worried that the secret site of the preparations for armed action would become known and that our enemies would discover the true nature of the import-export companies we had set up in South America.

Che Guevara had left Algiers by the time of the military coup on June 19, 1965. He had warned me to be on my guard. His departure from Algeria, his death in Bolivia, and my own disappearance for 15 years need to be studied in the historical context of the ebb that followed the period of victorious liberation struggles. After the assassination of Lumumba, it spelled the end of the progressive regimes of the third world, including those of N'Krumah, Modibo, Keita, Sukarno and Nasser, etc.[8]

The date October 9, 1967, is written in fire in our memory. For me, a solitary prisoner, it was a day of immeasurable sadness. The radio announced the death of my brother, and the enemies we had fought together celebrated their sinister victory. But as time passes, and the circumstances of the guerrilla struggle that ended that day in the Ñancahuazú fade from memory, Che, more than ever, is present in the thoughts of all those who struggle and hope. He is part of the fabric of their daily lives. Something of him remains attached to their heart and soul, buried like a treasure in the deepest, most secret, and richest part of their being, rekindling their courage and renewing their strength.

One day in May 1972, the opaque silence of my prison, jealously guarded by hundreds of soldiers, was broken by a tremendous din. I learned that Fidel was visiting a model farm only a few hundred yards away, no doubt unaware of my presence in the secluded Moorish house on the hill whose roof he could glimpse above the treetops. It is certainly for the same reasons of discretion that this very house was, not so long ago, chosen as a torture centre by the colonial army. At this moment, the memories flooded back. A kaleidoscope of faces passed before my eyes like an old, faded newsreel. Never since we parted had Che Guevara been so vivid in my memory.

In reality, my wife and I have never forgotten him. A large photograph of Che was always pinned to the wall of our prison and his gaze witnessed our day-to-day life, our joys and our sorrows. But another smaller photo, cut out of a magazine, which I had stuck onto a piece of card and covered with plastic, accompanied us on all our wanderings and is the one that is closest to our hearts. It is now in my late parents' house in Maghnia, the village where I was born, where we deposited our most precious souvenirs before going into exile. It is the photograph of Ernesto "Che" Guevara stretched out on the ground, naked to the waist, blazing with light. So much light and so much hope.

Notes

1. On Oct. 22, 1962, President Kennedy initiated the "Cuban missile crisis," or October Crisis as it is known in Cuba. The U.S. president ordered a total blockade of Cuba, threatened an invasion of the island, and placed U.S. forces around the world on nuclear alert. Washington demanded the removal of Soviet nuclear missiles, which had been installed in Cuba by mutual agreement of the two sovereign powers. Cuban workers and farmers responded by mobilizing massively in defense of the revolution. Faced with the determination of the Cuban people, and the knowledge that an assault on Cuba would result in massive U.S. casualties, Kennedy negotiated with Soviet Premiere Nikita Khruschev, who decided to remove the missiles without consulting the Cuban government.

2. Fellah is the Arabic for peasant. Harkis were counterrevolutionary auxiliary troops organized by the French colonial army in North Africa.

3. In 1963 Moroccan forces, backed by Washington, invaded Algeria, which had won its independence from France the previous year after an eight-year revolutionary war. At Algeria's request, the Cuban government sent a column of troops under the command of Efigenio Ameijeiras, a veteran of the Cuban revolutionary war, to help stop the attack. The mere presence of Cuban troops forced the Moroccan government to back down and withdraw its forces.

4. Approximately $3.3 million at current exchange rates.

5. This speech appears in Che Guevara Speaks, published by Pathfinder Press.

6. Stanleyville was the former name of Kisangani, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire). Between April and December 1965, Guevara led a contingent of more than 100 Cuban volunteers assisting revolutionary forces that were fighting the regime in Congo, which was backed by Belgian, South African, and other imperialist forces. In January 1961 Patrice Lumumba, the leader of the fight for independence from Belgium and first prime minister of the Congo, was murdered by pro-imperialist forces backed by Washington, after being disarmed by a U.S.-led United Nations "peacekeeping" intervention.

7. The presidents of Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Egypt, Mali, Ghana, Kenya, and Guinea respectively.

8. Sukarno was the president of

Indonesia until 1967.

Ahmed Ben Bella was the central leader of the Algerian National Liberation Front which led the struggle for independence from France. He was the president of the revolutionary workers and farmers government that came to power following the victory over France in 1962. He was overthrown in a counterrevolutionary coup led by Col. Houari Boumediene in June 1965.

(Originally published in the October

1997 issue of Le Monde diplomatique on the 30th Anniversary of the

Death of Che Guevara. English translation and end notes by The

Militant, Vol. 62, no. 4, 2 February 1998)

Coming

Events

Homage to Che Guevara

Ottawa

Vancouver

Photo

Review

Che Guevara's Life

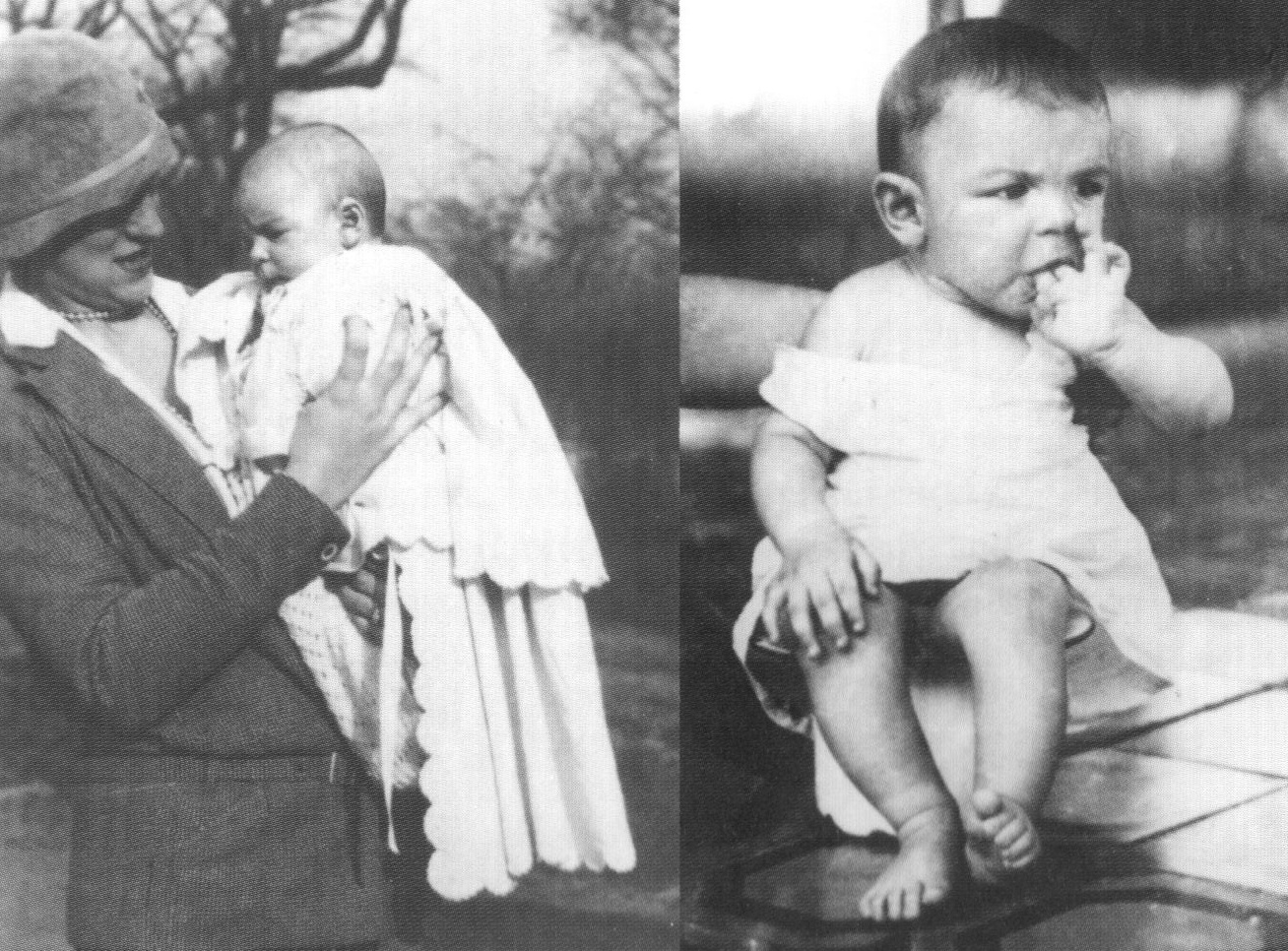

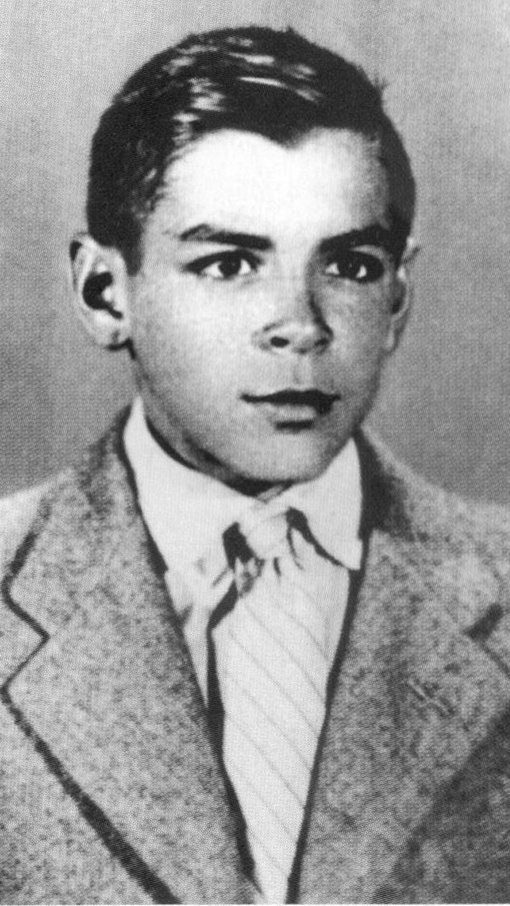

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was the firstborn child of Celia de la

Serna and Ernesto Guevara Lynch, a middle-class Argentinian family,

shown here with his mother at the age

of

one-month in Rosario, Argentina, July 1928.

Ernesto with his parents and four siblings on holiday in Mar del Plata,

Argentina, 1943.

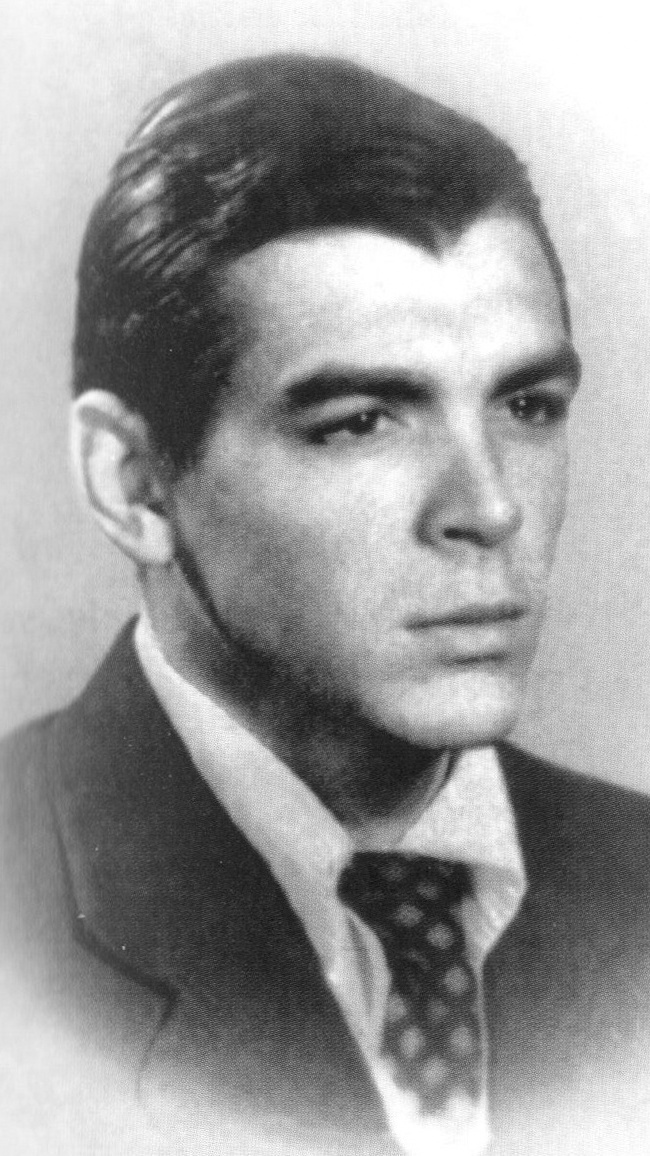

Ernesto at age 12 and 15 while living in Alta Gracia, Córdoba; and age

20

in Buenos Aires. As a child, his family moved from Rosario to the drier

climate of

Alta Gracia due to his severe asthma. As a youth, Che was an avid

sportsman, known by his teachers and peers for his maturity, high

spirits, independence and disregard for danger, as well as the high

standards he set for himself.

Ernesto in his first year of medical school in Buenos Aires, 1947 -- he

is in the back row, sixth from the right, smiling broadly.

Ernesto, holding the ball, with his rugby team in Buenos Aires in

1949.

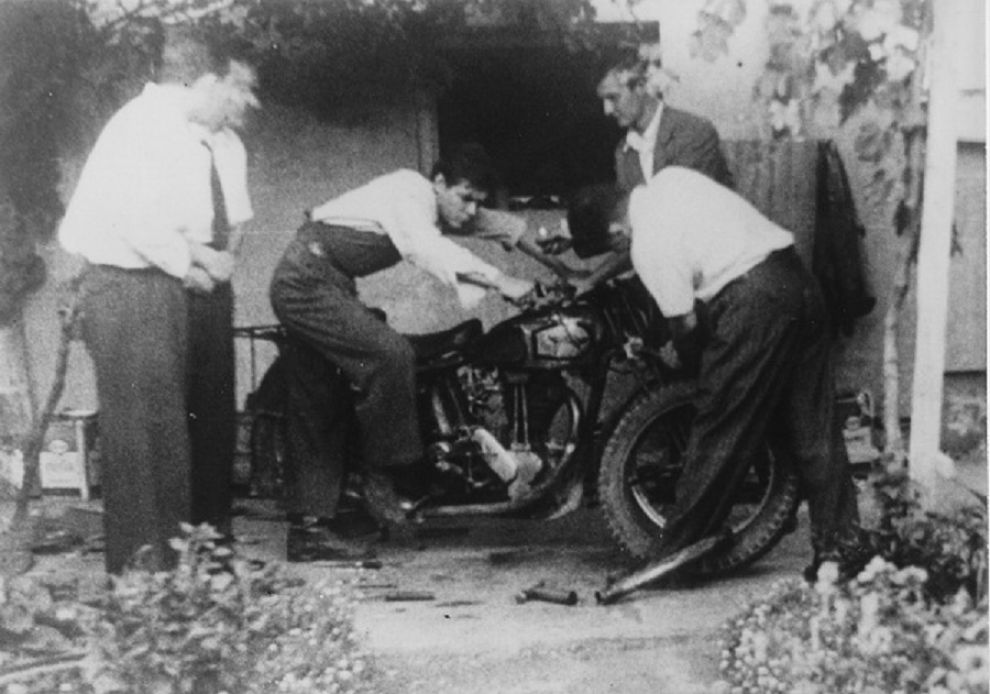

Ernesto's first trip across Argentina began in 1951 by motorized

bicycle, and included a

visit to see his friend Alberto Granado in Córdoba (centre). He

continued northeast to the country's

poorest provinces of Santiago del Estero, Tucumán, Salta, Jujuy,

Catamarca, and La Rioja,

returning via San Juan, Mendoza, San Luis, and south to Nahuel Huapí.

He traveled a total of

4,500 kilometres.

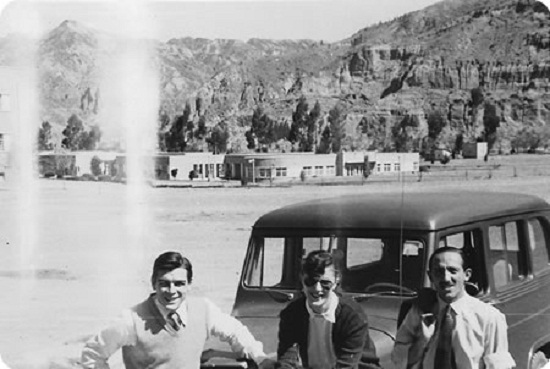

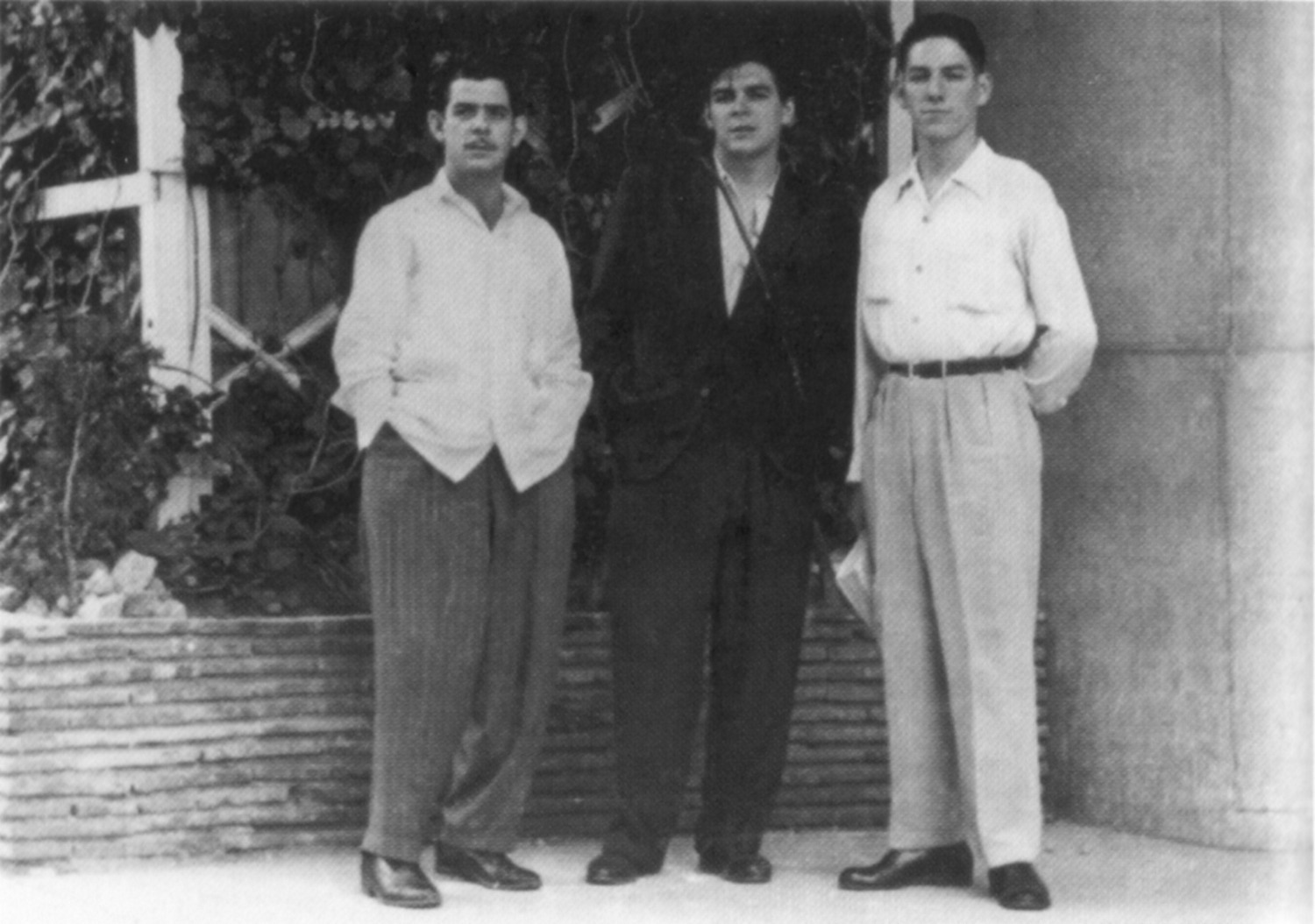

Ernesto with his friends in Argentina, October 1951, including Alberto

Granado, as the two prepare for the trip across South

America, recounted in The Motorcycle

Diaries. He and Alberto took a year off from their studies for a

nine-month journey that included Chile, Peru (Cuzco, Macchu Pichu and

Lima), Bogota, Colombia and Caracas, Venezuela.

This photo shows Alberto and Ernesto

with their raft the Mambo-Tango

that took them to the Peruvian leper colony where they served as

doctors.

The injustices and suffering of the people galvanized

Che

on a course toward revolutionary politics. Their trip concluded July

26,

1952, in Venezuela and Ernesto

returned to Buenos Aires via Miami to complete medical school.

On June 12, 1953, Ernesto graduated medical school,

and on July 7 began a second trip across the continent, on this

occasion, with his childhood

friend Carlos "Calica" Ferrer, shown here with Che in Bolivia. Their

goal was to reach Caracas, where Alberto Granado was

waiting for them.

Later in 1953, Ernesto returned to Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador, and

reached

Panama and Costa Rica, where he first came into contact with Cuban

revolutionaries who had participated in the assault on the Moncada

Garrison in Santiago de Cuba, July 26, 1953, among them Calixto García.

He met Antonio Ñico López in Guatemala. Left: Che in Costa Rica

in 1953; right: on the road to Guatemala to support the progressive

government

of Jacabo

Arbenz.

After the Arbenz government was brought down

by a coup, Ernesto traveled

to Mexico, arriving September 21, 1954.

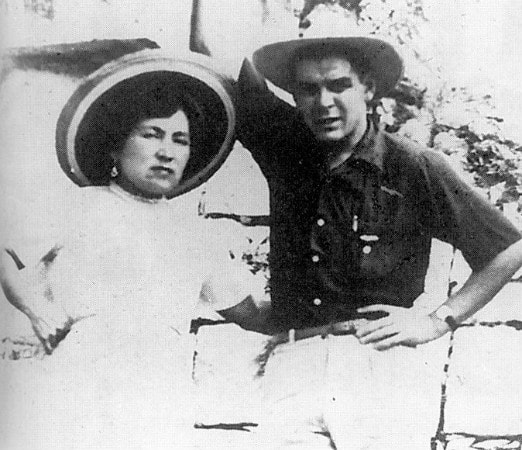

In Mexico City, events moved rapidly. Ernesto married

Hilda Gadea (shown here on their honeymoon in Chichen Itza), his first

daughter Hilda Beatriz was born (shown here with Che during the

imprisonment of the July 26 Movement in Mexico City), and he met the

leader of the July 26

Movement, Fidel Castro, in the home of Cuban María Antonia González, at

49 Emparán

Street.

The July 26 Movement began training in guerrilla warfare, with their

instructor, a Cuban Army veteran, remarking on Che's aptitude.

Left: climbing Popocatepel, Mexico City, October 12, 1955; right:

weapons training, Mexico City, 1956.

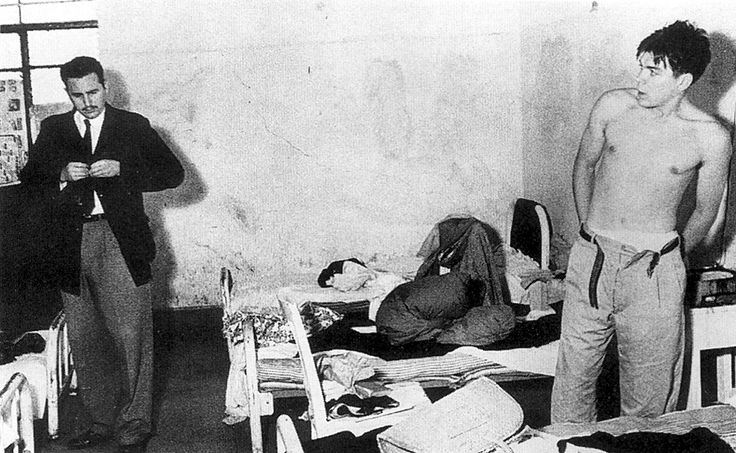

Che with the July 26 Movement in Mexico, in 1956,

imprisoned at the Miguel-Schultz detention centre after

being arrested under immigration laws.

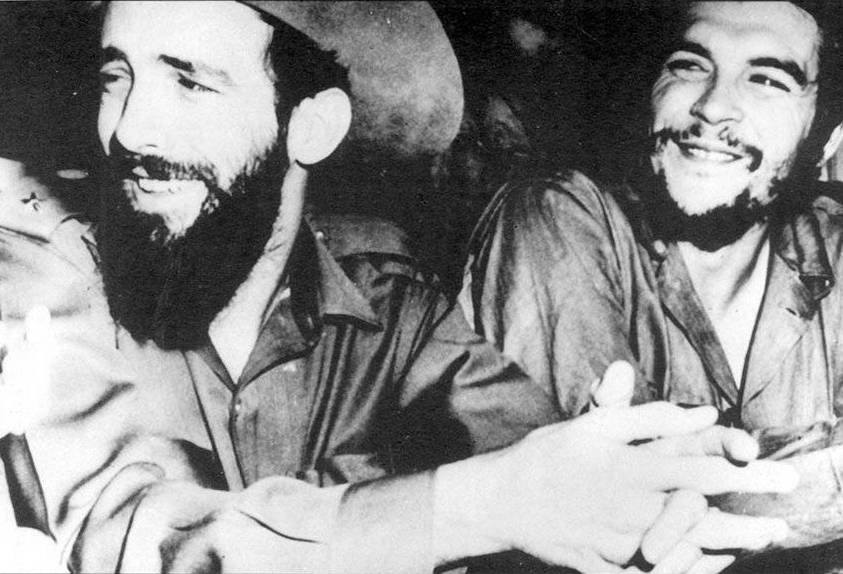

The first photo of Fidel and Che together, at the detention centre in

Mexico City. In a letter to his parents on July

6, 1956, Che wrote, "... my future is tied up with the Cuban

Revolution.

I will either triumph alongside it or die there."

On November 25, 1956, 82 members of the July 26 Movement boarded the Granma under cover of darkness in the port of Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico, and undertook a 13-day voyage to Playa Las Coloradas in what was Oriente province.

Map of Che's journey across Cuba in the period before and after the

triumph of the Cuban Revolution. Click to enlarge.

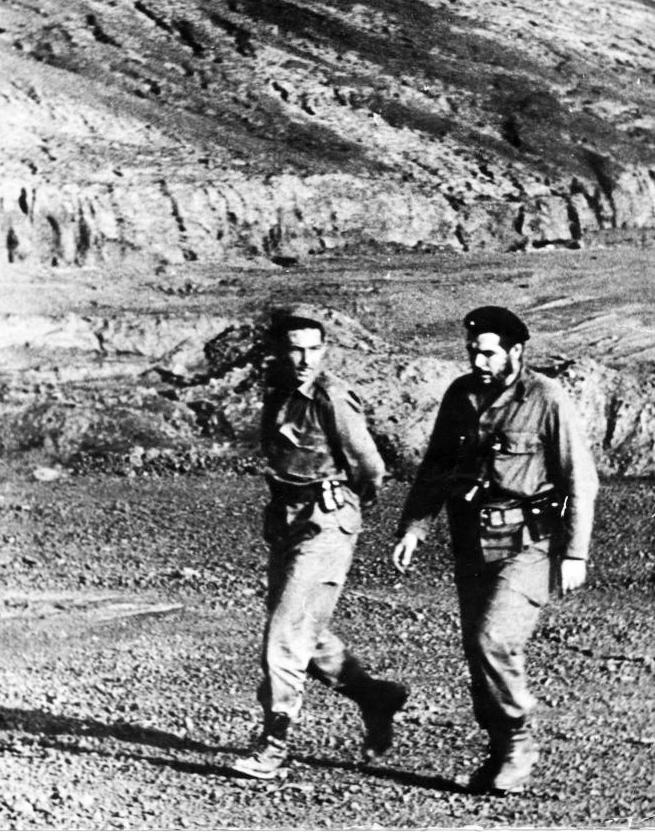

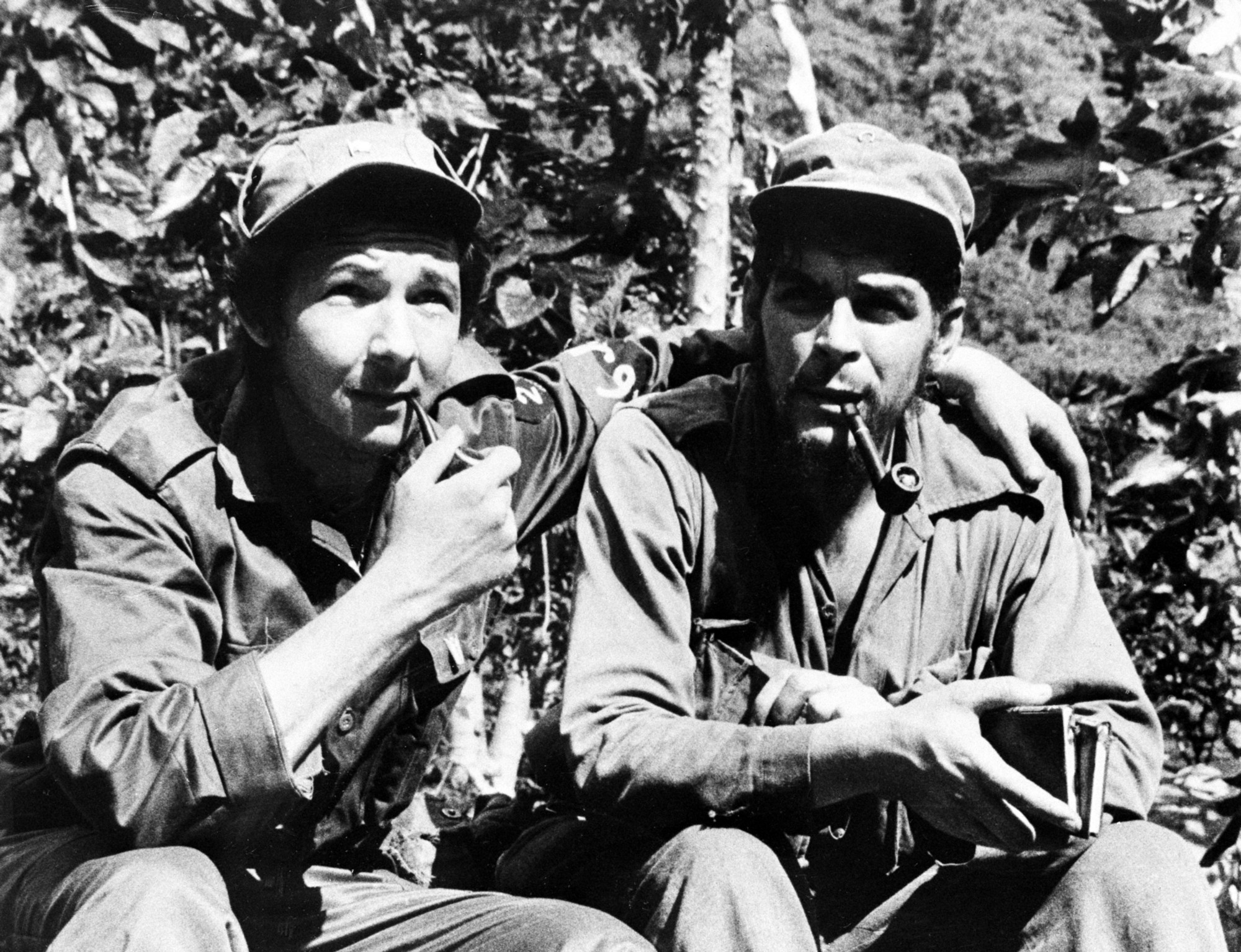

Che and Fidel in the

Sierra Maestra, October 8, 1957.

Raúl and Che in the Rebel Army's stronghold on Sierra de Cristal

mountain in then-Oriente province, 1958. Che

had originally joined the July 26 Movement to be its combat medic, but

with his formidable leadership he was tasked to be a military commander

in the Rebel Army.

Cuban guerrillas in the Rebel Army's 4th Column led by Che Guevara

celebrate New Year's 1958. Che's autonomous column began operations in

late July 1957 and was the

first troop to emerge from the original

guerrilla force.

Radio Rebelde was founded by Fidel, Che and the Rebel Army on February

24,

1958 in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Its first-hand reports on battles

against the Batista Army and denunciations of the dictatorship

mobilized the Cuban people and demoralized the enemy.

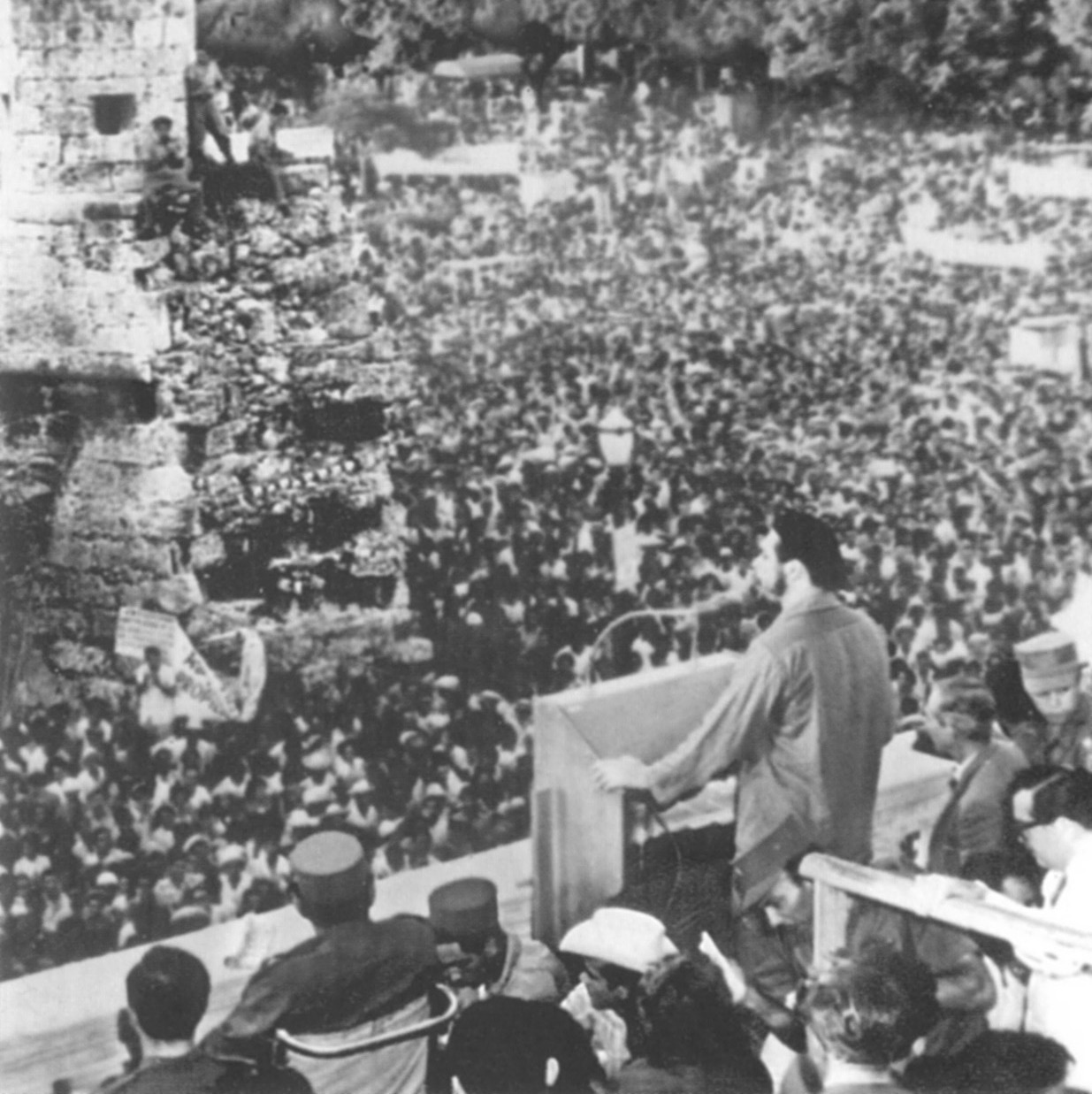

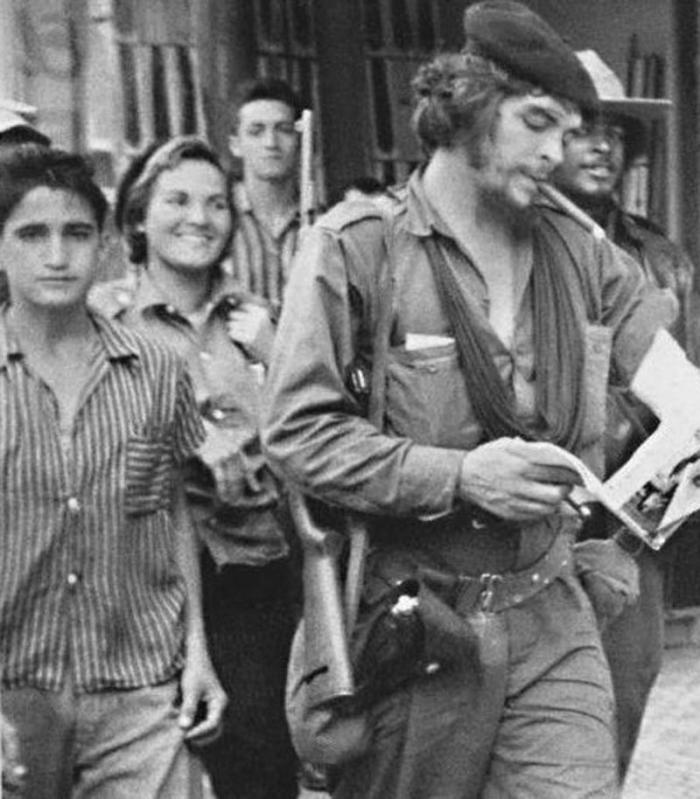

Che addresses the residents of Fomento, Las Villas province, November

1958. This was the first

city in the region liberated by the rebel forces led by Che

before ultimately winning the entire region. From here they

moved to central Cuba and the decisive battle of Santa Clara.

The Battle of Santa Clara, December 1959. Left: the Rebel Army used

tractors to derail an armoured train full of enemy troops and weapons,

December 29, 1958. Right: Che with Santa Clarans, December 31,

1958, after he led the Rebel Army to victory; to his left is his fellow

revolutionary and future wife Aleida March. Shortly after the Batista

Army's defeat in Santa

Clara, it totally surrendered.

Che, Fidel and Camilo Cienfuegos were welcomed at a mass rally in

Havana, January

8, 1959, after Fidel took the Rebel Army across the country in an

historic

Caravan of Victory.

Che and fellow Rebel Army commander Camilo Cienfuegos in 1959, with

whom he was particularly close. Today the two remain side by side in

Revolution Square, with Che's portrait adorning the Ministry of the

Interior and Camilo's on the Ministry of Informatics and

Communications. In October that year, Camilo died in a plane crash. Che

later named

his son after him.

Che's second marriage, to Aleida March, on June 2, 1959. Aleida

recalled their

time together waging armed struggle: "I can't say I'm

Che's

secretary, because I'm a fighter. I fought beside

him in the Las Villas

campaign and took part in all the engagements there. That makes me his

orderly... When it became practically impossible for me to continue

living in Santa Clara, due to my revolutionary activities, I decided to

join the ranks of those fighting the dictatorship by

taking up arms."

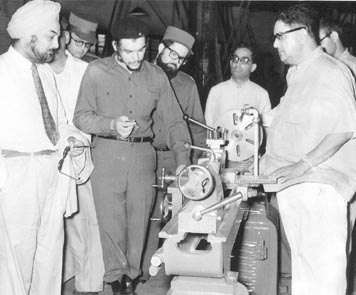

Che in Gaza, 1959. This visit was part of an extended trip through

Europe, Africa and Asia

from June 12

to September 8, where he was tasked

with developing Cuba's trade

and diplomatic relations.

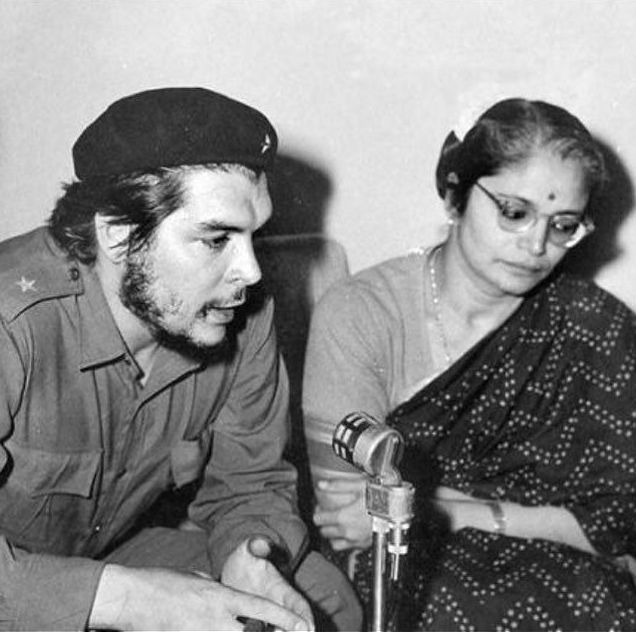

Visit to India, July 1959. Left: Che examines a lathe at a factory in

New Delhi; right: giving an interview on Delhi

Radio.

Left: Che is greeted by Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito; right:

visit to Pakistan.

Left: Che with President Kusno Sukarno in Indonesia; right:

being greeted by

Egyptian

President Gamal Abdel Nassar on his visit to that country.

Che in Red Square during a 1960 visit to Moscow.

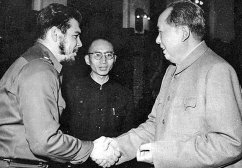

Left: Che visits the DPRK in 1960; right: meeting Chairman Mao in China

in 1960.

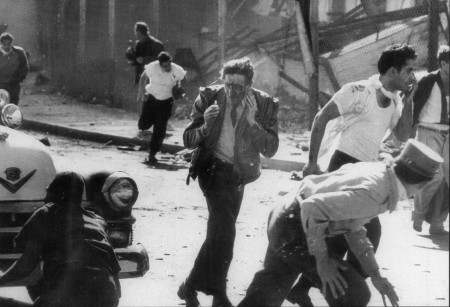

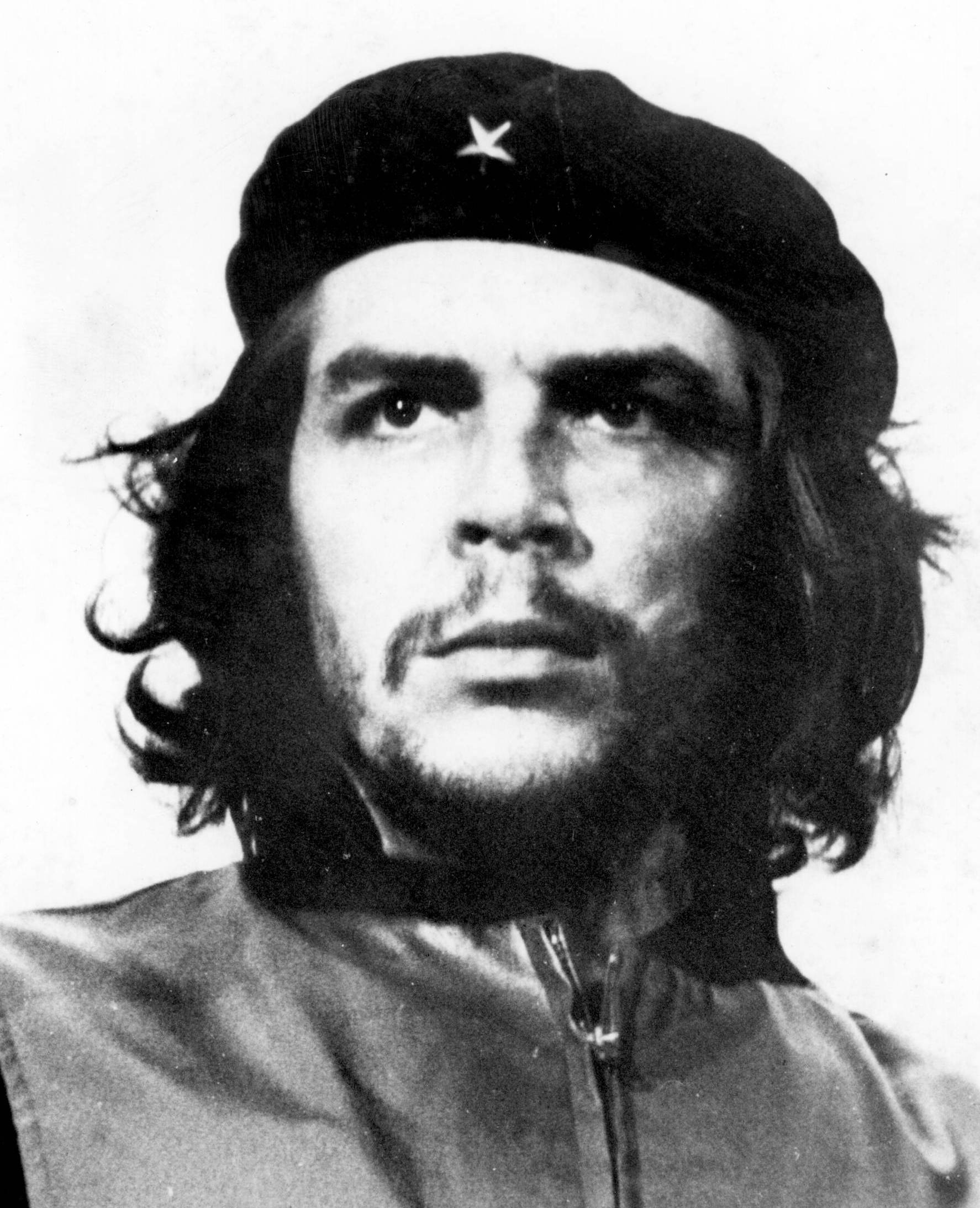

March 4, 1960: A terrorist act destroyed the French ship La Coubre in Havana. The most

famous photo of Che was captured

by Alberto Korda on March 5, 1960 during the mass

funeral to the victims of this counterrevolutionary sabotage.

May Day 1960, Santiago de Cuba. For the first two years of the

Revolution, Che returned there to take part in May Day

celebrations.

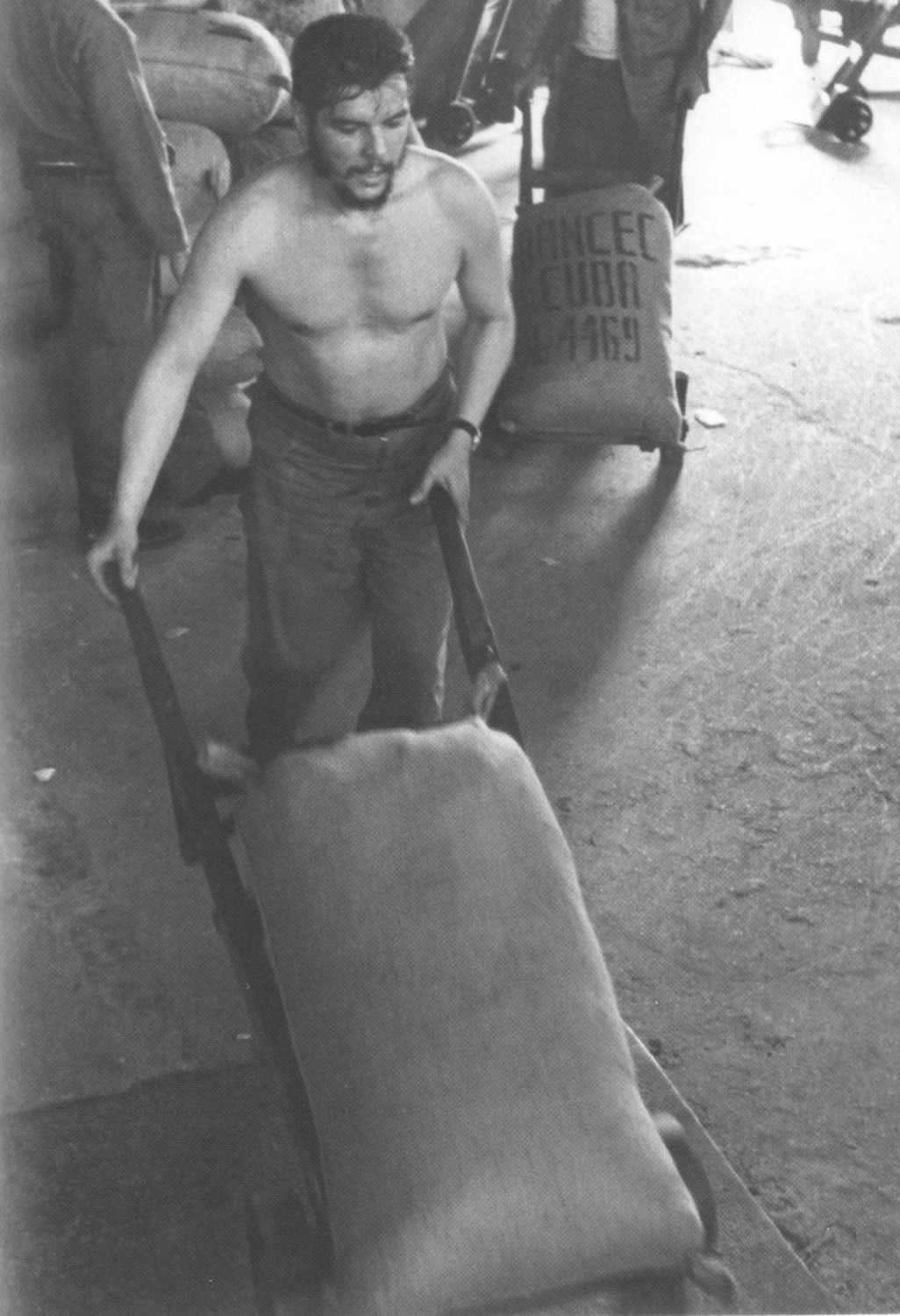

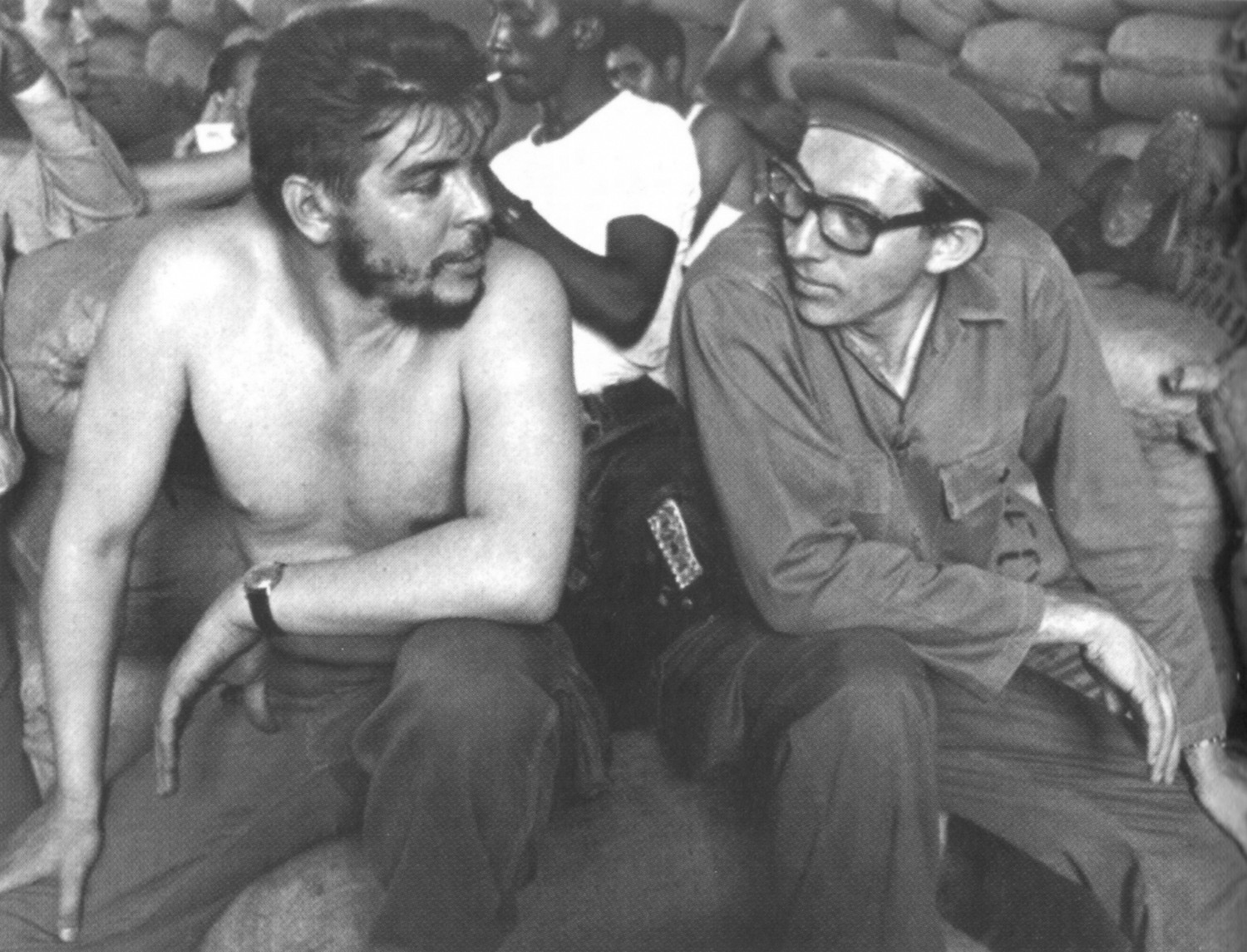

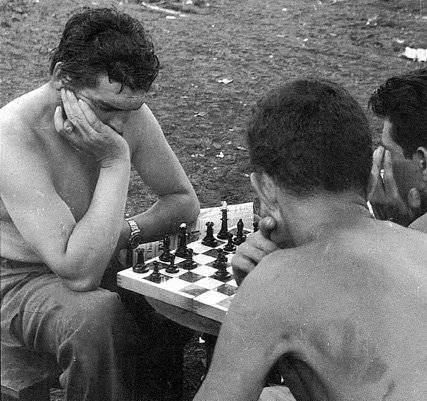

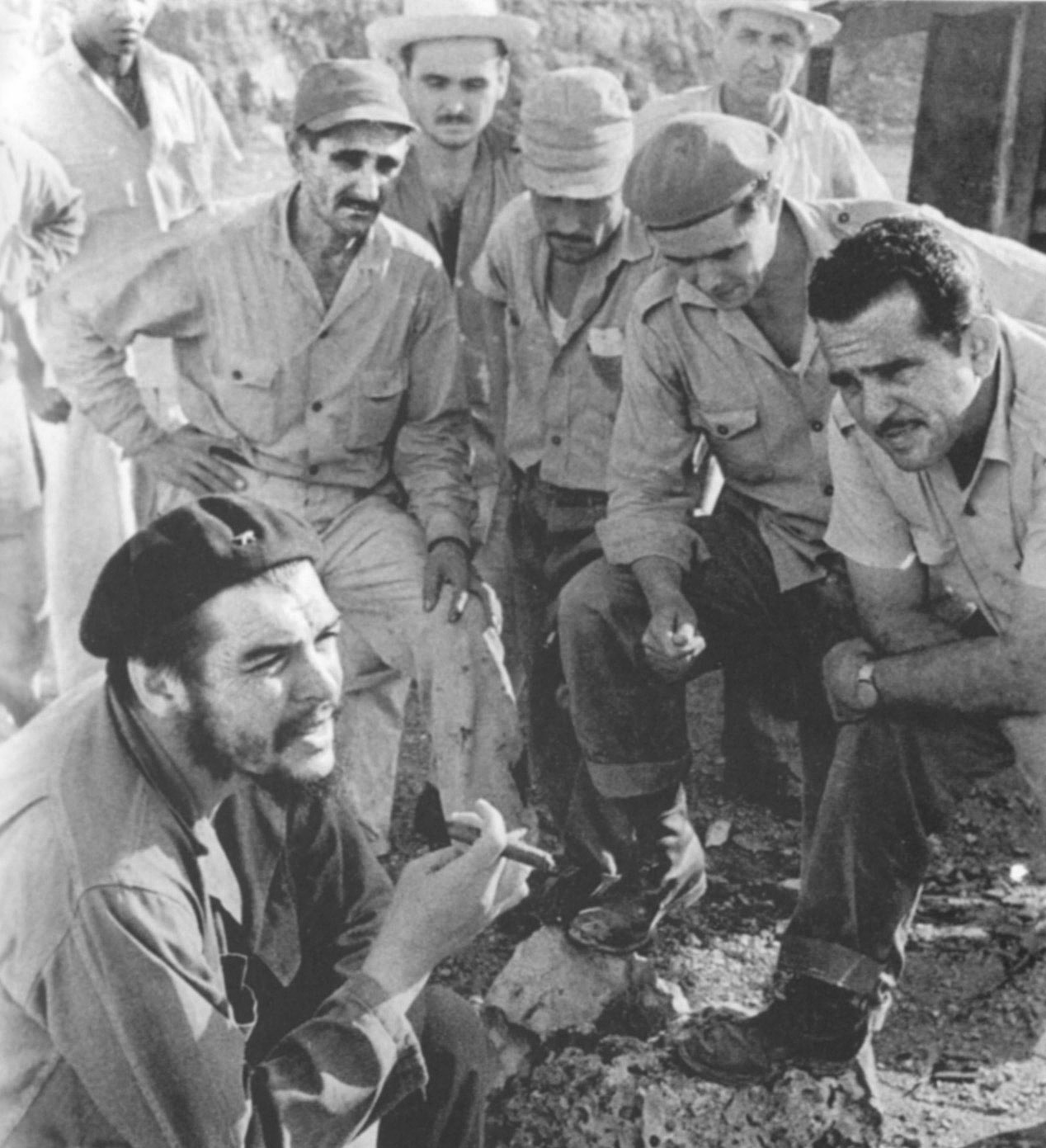

Che urged Cubans to take

part in voluntary labour to create the consciousness needed for the new

society and made

sure he led by example, joining the workers after completing his duties

at the Ministry of Industry or on weekends. Top: Che cuts sugar cane

with his old

friend

Alberto Granado (who moved to Cuba at Che's invitation in 1960) and

Aleida March. Centre: at the Port of Havana in 1961, with Orlando

Borrego, his colleague at the Ministry of Industry, an economist who

later edited seven volumes of Che's writings. Bottom left: Che, an avid

and skilled chess player, plays a match after finishing his volunteer

work, 1962. Right: Che takes a

break with cement factory workers in Artemisa,

Pinar del Rio, 1964.

Cuba's historic literacy campaign was the initiative of Che and Fidel

and raised the literacy rate to 96 per cent. On December 21, 1961, they

joined celebrations with Cuban literacy workers to mark the completion

of the year-long campaign.

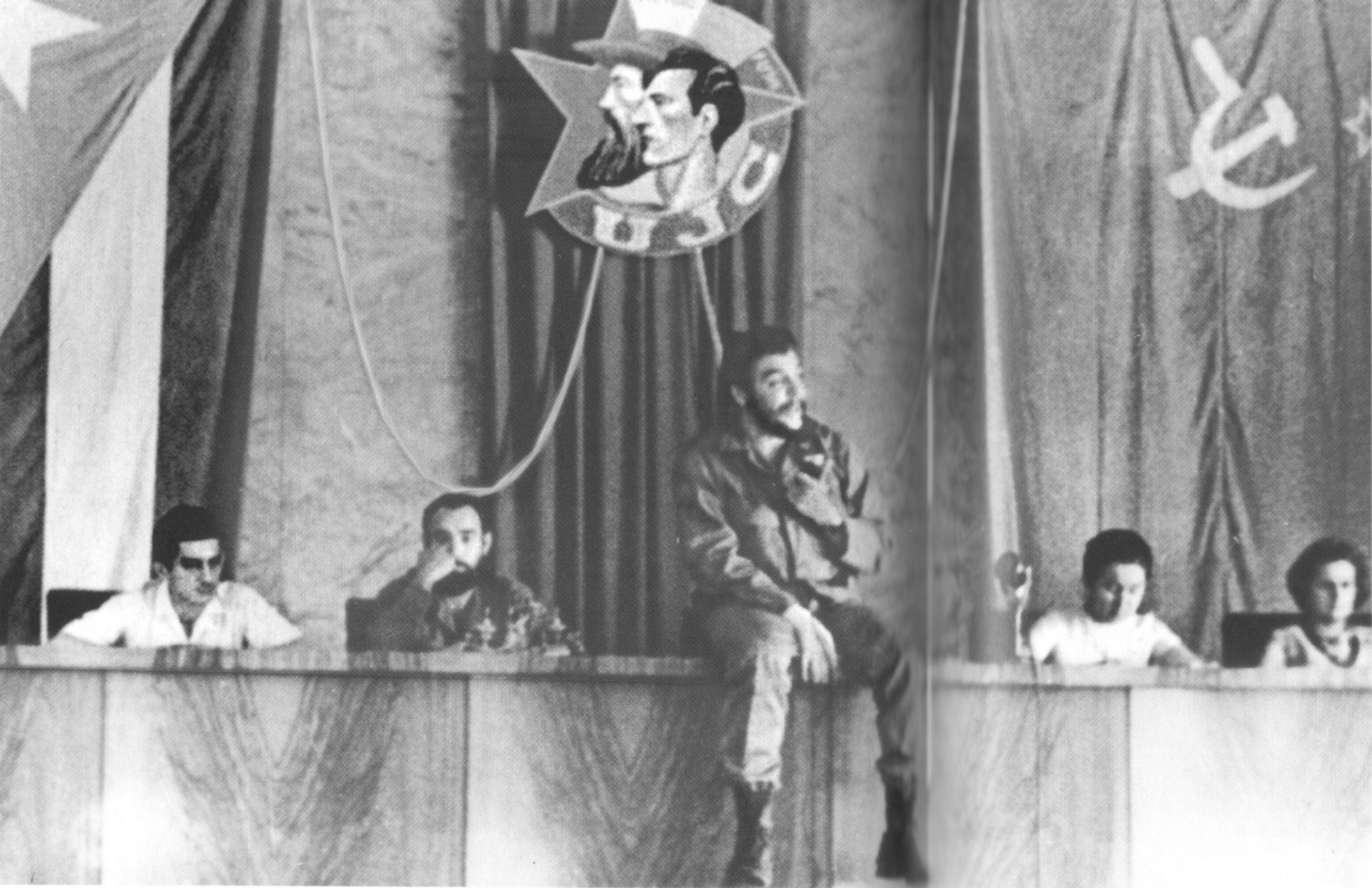

Che speaks to the youth at a meeting of the Union of Young Communists,

October 20, 1962.

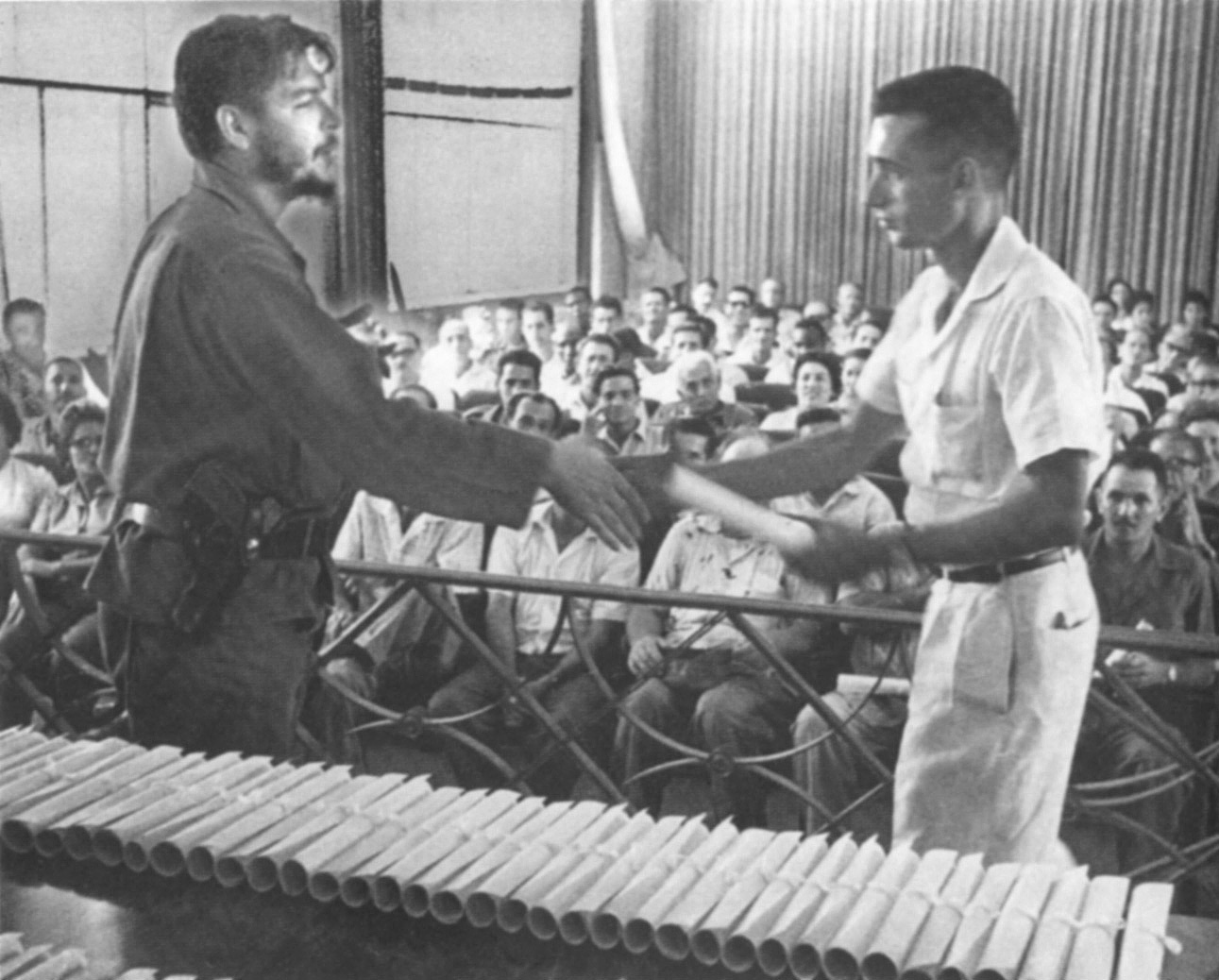

Che was keen to ensure the workers saw the necessity of their

contributions to the Revolution, highlighting those who excelled in

their fields, such as at this event in June 1962, one of the monthly

ceremonies held to recognize distinguished workers.

Che visits workers at the Ñico Lopez sugar refinery in Havana, 1963.

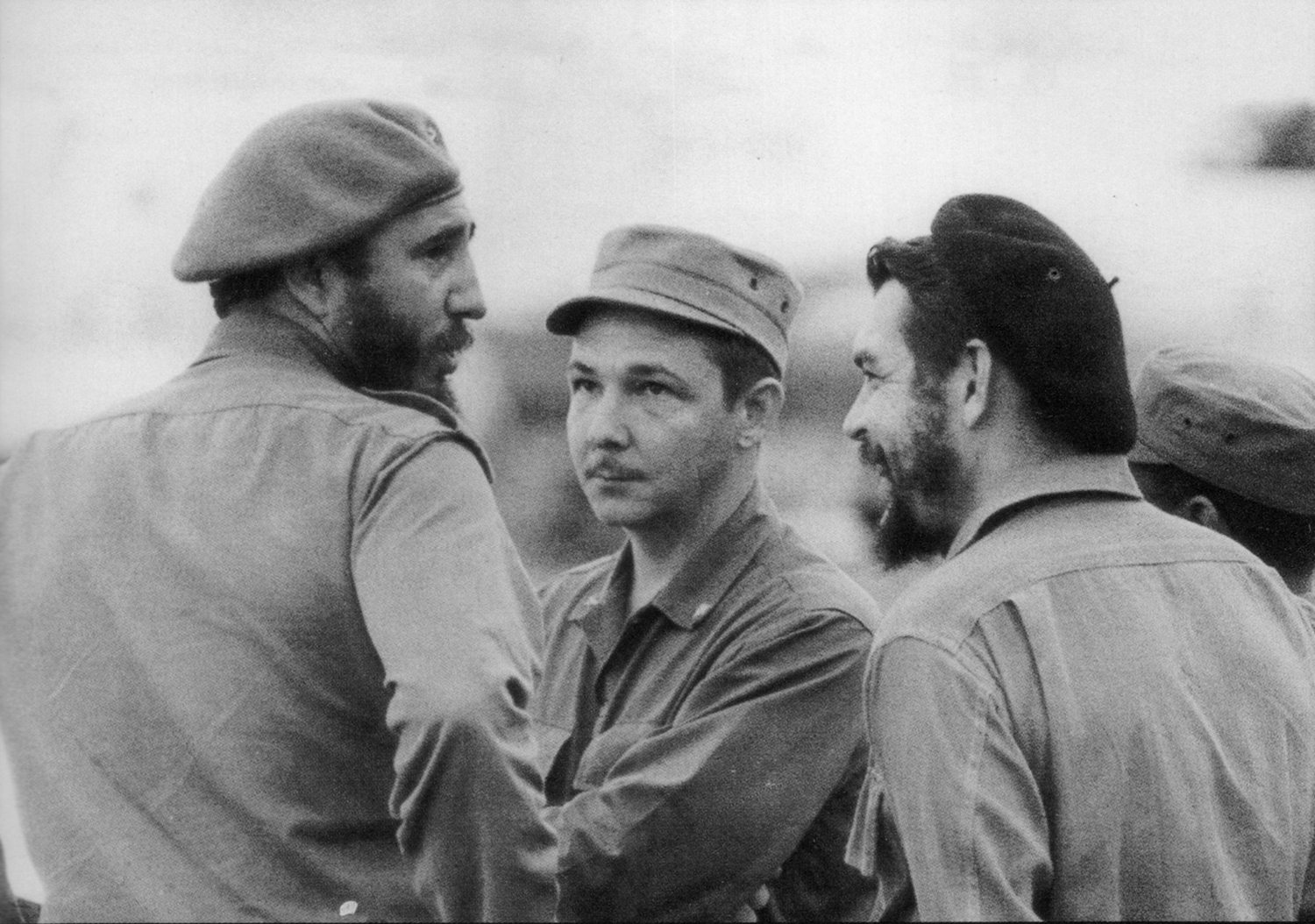

Fidel, Raúl and Che in 1963.

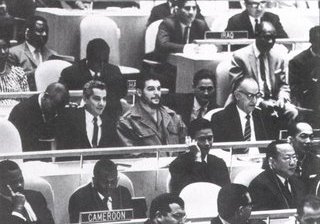

Che addresses the United Nations, December 11, 1964, as head of the

Cuban delegation.

Che and Aleida with their children in 1965.

Che departed Cuba in 1965, to take up the armed struggle for national

liberation in other countries. He secretly led a dozen Cuban fighters

on April 24,

1965, to join rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo, fighting the

pro-imperialist regime

in Kinshasa established after the coup organized by the U.S. and

Belgium. Patrice Lumumba, the first president elected when

Congo won independence in 1960, was assassinated in the coup.

During his tour of Africa in 1965, Che meets with Agostinho Neto and

MPLA fighters at their headquarters in Brazzaville in the Congo.

Che quietly returned to Cuba from the

Congo and prepared to depart for Bolivia. Here, in Pinar del Rio in

1966, he altered his appearance (third from the right) and trained with

other guerrillas in preparation for taking up

the armed struggle in Bolivia.

Che and the guerrillas of the Bolivian National Liberation Army share

Christmas dinner, 1966.

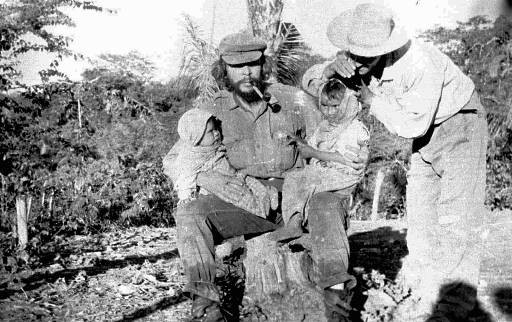

Che with a local farmer in 1967, to whose children he provided medical

care. The farmer

would betray him to the Bolivian army shortly after.

Che's funeral cortege takes his remains from Revolution Square in

Havana, October 13, 1997, to the newly built Mausoleum to

Che in Santa Clara the

following day. Che's remains were positively identified in Bolivia by a

team of Cuban

archaeologists and forensic experts three months earlier on July 12,

1997.

Che's daughter Aleida Guevara speaks at the Mausoleum to Che in Santa

Clara with Fidel,

Raúl and other leaders of the Cuban people. October 17, 1997.

Che Guevara's Monument and Mausoleum in Santa Clara, Villa Clara.

Videos

Excerpts from Che's famous address to

the UN General Assembly as head

of

Cuba's

delegation to the UN, December 11, 1964.

Posters of OSPAAAL

Che Guevara was often tasked with representing the nascent Cuban Revolution in relations with other countries and in international fora. In the years since his assassination, Organization of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America has commemorated Che and his internationalist spirit with a series of posters. Click to enlarge.

(Photos and videos: www.fidelcastro.cu,

OSPAAAL, The Che Handbook, Cuban Office of Historical Affairs, Cien

Imagenes de la Revolucion Cubana, Centro de Estudios Che Guevara,

Ecured, Granma, A. Korda, R.A. Torres, O. Salas, L. Noval, J. Nilsson,

Prensa Latina, Kaldari, M.S. Johnson)

|

|

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca

As a stellar leader, Che

mobilized the people to carry

out

the necessary tasks. When the U.S. engaged in economic subversion

and then launched terrorist attacks against the nascent

revolution, Che did not flinch but joined the ranks of the

revolutionary fighters to rally the Cuban people to fight back.

His contribution to set Cuba on the socialist road and safeguard

the Revolution left an indelible mark on what Cuba stands for

today.

As a stellar leader, Che

mobilized the people to carry

out

the necessary tasks. When the U.S. engaged in economic subversion

and then launched terrorist attacks against the nascent

revolution, Che did not flinch but joined the ranks of the

revolutionary fighters to rally the Cuban people to fight back.

His contribution to set Cuba on the socialist road and safeguard

the Revolution left an indelible mark on what Cuba stands for

today.