|

October 3, 2017 - No. 30 Recognition of the Hereditary Rights of Indigenous Peoples Must Come First

• Beware of

Trudeau Government's Changes to the Indian

Act Indigenous Rights Recognition of the Hereditary Rights of

|

|

|

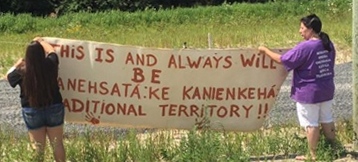

TQM is accused of covertly expanding existing gas pipelines on traditional Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory that has never been ceded, contrary to what the federal and Quebec governments or the Mayor of Oka want people to believe. "The administration of Oka Park would have the public believe that the only new activity is the repaving of the existing bike path and that no new gas pipelines have been installed," said the people's statement.

Ellen Gabriel, a spokesperson for the Kanehsata'kehró:non, explained that those traditional territories have belonged to the Kanehsata'kehró:non long before the Sulpician Order came to settle in the area in the 18th century. Gabriel spoke about the refusal of the federal and Quebec governments to address the issue, by either not returning her calls, as is the case with the Quebec Minister responsible for Aboriginal Affairs, or by stalling tactics, in the case of the Trudeau government. Every time Gabriel and other representatives of the Mohawk community have tried to meet with Carolyn Bennett, federal Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, her assistants would answer, "She is too busy now, we need to reschedule," while at the same time declaring that "the Minister really wants to talk with you."

Gabriel said, "The silence and denial of government's assumed fiduciary obligations to intervene is a disturbing signifier that Canada intends to continue business as usual as it has done for the past 150 years of genocide and dispossession. There is no Reconciliation towards the Kanien'kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke, a matter that could have been resolved 27 years ago [during the 1990 Oka Crisis], and can still be resolved using the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as the framework of reconciliation and restitution. But reconciliation must include reparations and respect for all Indigenous peoples' human rights."

The press conference concluded with the reading of several demands of the women and Rotinonhseshá:ka (People of the Longhouse) to Canada and Quebec:

- An immediate moratorium be implemented to stop any and all development on the traditional territory of the Kanien'kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke;

- That Canada begin discussions with the Rotinonhseshá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke to resolve the long standing historical land dispute;

- That Canada revoke the Doctrine of Discovery upon which it bases its sovereignty and justification of land dispossession;

- That Gregoire Gollin, owner of Collines d'Oka, and the municipality of Oka cease and desist from selling any land in Kanehsatà:ke and refund the people who have bought disputed land at the illegal development site (see item below);

- That TransCanada and Gazoduc remove their newly-installed pipelines from Kanehsatà:ke and compensate the Kanien'kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke through a trust fund of our creation. This trust fund will support the rebuilding of the traditional institutions that were targeted by Canada, including the traditional government of the Rotinonhseshá:ka, our culture and our Kanien'keha language; and

- That any development to take place on our traditional territory of the Kanien'kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke uphold international human rights standards, in particular the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and its principle of free prior and informed consent.

They underscored the necessity for governments to uphold the Rule of Law and the peoples' right to say "No," saying that "the Rule of Law requires implementation of various Supreme Court of Canada decisions like Sparrow and Delgamuukw, which require consultation and accommodation of 'Aboriginal peoples.' More importantly, Kanien'kehá:ka traditional customary law governs any development impacting our lands, territories and resources and requires the consent of the Kanien'keháka Nation before it can proceed. And, not just their government funded band councils."

A traditional ceremony led by an Indigenous elder ended the press conference and everyone present was invited to the Southwestern edge of Oka National Park to see the area where Gazoduc TQM has started underground expansion of the existing gas pipeline.

Note

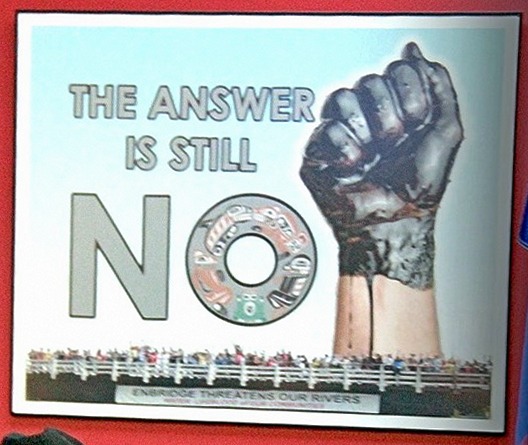

1. TransCanada is behind the widely-opposed Energy East

Pipeline Project. The Energy East project

aims to transform a 40-year-old 2,000-km gas pipeline into an oil

pipeline to transport "dilbit" from the tar sands to the east

coast. Dilbit or diluted bitumen is a toxic mixture of tar sands

bitumen and chemicals used to make it thin enough to pump through

pipelines. There is great concern about the danger this poses to

the land and water. The pipeline crosses the Ottawa River near

Oka, Quebec where the river becomes the Lake of Two Mountains,

upstream from metropolitan Montreal, which is the sole

source of drinking water for close to three million people. A

federal government report recently confirmed that dilbit sinks

when mixed with sediment, which would make waterway cleanup

efforts extremely difficult. This is consistent with the U.S.

experience of the massive 2010 dilbit spill in Kalamazoo,

Michigan, where more than $1 billion has been spent on cleanup

efforts but the river is still polluted.

(Photos: E. Gabriel)

Provocative Land Development Begins at

Site of 1990 Oka

Crisis

An illegal housing development is underway in Oka, Quebec, on land known locally as "The Pines" that is claimed by the Kanehsata'kehró:non (people of Kanehsatà:ke). This encroachment of Mohawk land is precisely where developers illegally sought to build a golf course in 1990. Protests have taken place over the summer, exactly 27 years after the 1990 Oka Crisis saw the Canadian state wield massive military force against the Mohawk's just defence of their land.

Steve Bonspiel, editor and publisher of Kahnawake's weekly newspaper The Eastern Door, in a CBC op-ed, published July 11, the 27th anniversary of the resistance at Oka, noted the refusal of the Canadian state to do its part to resolve the situation:

"The land in dispute? It's

still in the hands of Oka. Mohawk

land -- illegally taken. Yet no one is doing anything to take it

back.

"The land in dispute? It's

still in the hands of Oka. Mohawk

land -- illegally taken. Yet no one is doing anything to take it

back.

"Forget the negotiations; it's our land, so why is Canada dealing all the cards? Shame on the municipal, provincial and federal governments, all of which continue to be complicit in the oppression and control of our people.

"What kind of 'proud' country continues to profit off the theft of our land, and continually denies our right to get some of it back, yet tells everyone how great it is by celebrating 150 years of colonialism?

"If anything, we should be talking about the return of all illegally begotten Mohawk land, not just that small tract.

"If we keep allowing the outright thievery of what has always been ours, what will we have left...."

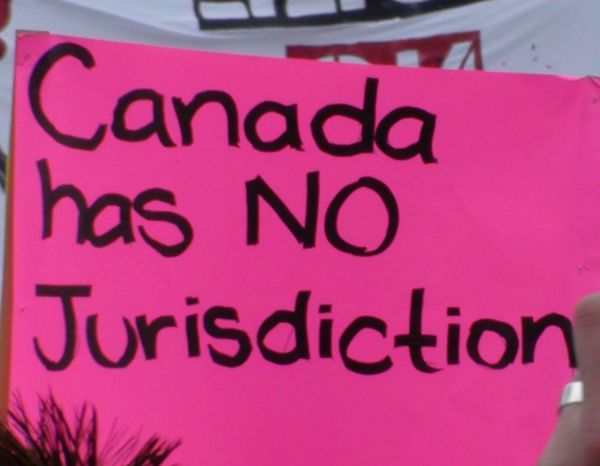

Despite nothing having been resolved since the events of 1990, the City of Oka has nonetheless granted permits for the housing projects on land over which it has no jurisdiction. A July 25 item in the National Observer notes:

"[Mayor of Oka Pascal Quevillon] says he cannot stop construction of the housing development or Oka could be sued and its citizens could pay 'millions' of dollars. He said he doesn't believe that would be fair to his community.

"'Only the federal [government] can tell us to stop authorizing the construction on these lands, but the federal [government] will have to financially compensate the land owner, the developer and the municipality if it does that.'

"He says this is a problem to resolve between the federal government and the Kanesatake community."

Why has the Canadian government neglected its duty to

rectify

the historical injustices and dispossession? Leaving the status

quo intact has inevitably created a situation where a repeat of

the 1990 Oka Crisis could happen. Will the Kanehsata'kehró:non

be

forced to physically block or eject the developer? Will the

Canadian state and monopoly media respond with racist and

hysterical claims about "violent Natives," claim economic damage

against the developer, and threaten the Kanehsata'kehró:non with

state violence once again? Clearly the spectacle of the armed

standoff in Oka in 1990, the broad public support for the

Kanehsata'kehró:non and the fact that major bloodshed was only

narrowly avoided -- due in no small part to caution and

discipline on the part of the Mohawk Warriors under the

leadership of their elders -- has not sobered up the Canadian

state and the ruling elite one bit in 27 years.

March marks 25th

anniversary of Oka

uprising, July 11, 2015.

If the government was sincere about finding a just solution to this land claim, it would obviously act quite differently and ensure that at least a moratorium on development is put in place until a negotiated resolution is reached, rather than permitting land developers to create facts on the ground that will only undermine the Kanien'kehá:ka land claims and negotiating position, and sow divisions between them and their neighbours in Oka. It is said the Canadian state is holding negotiations over the disputed land with the Mohawk band council elected under the auspices of the Indian Act. Even if this is true, such negotiations cannot possibly be in good faith when the people do not know what is going on, and the government will not intervene in situations such as this. The government's actions make clear that in Kanehsatà:ke and elsewhere, the aim of the Canadian state remains dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

The situation requires that people in Canada and Quebec do their duty and step up their support for the just demands of the Indigenous peoples, and organize for their own empowerment to bring modern arrangements into being based on genuine nation-to-nation relations and the recognition of rights.

The Pines Are Mohawk Land!

Developers

Get Off Mohawk Land!

No to a Repeat of the 1990 Oka Crisis!

Hold the

Canadian State to Account for the Dispossession of

Indigenous Peoples!

(Photos: E. Gabriel, S. Bonspiel, K. David)

For

Your Information

The White Paper 1969

"In spite of all government attempts to convince Indians to accept the white paper, their efforts will fail, because Indians understand that the path outlined by the Department of Indian Affairs through its mouthpiece, the Honourable Mr. Chrétien, leads directly to cultural genocide. We will not walk this path." -- Harold Cardinal, The Unjust Society

In 1969, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and his Minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chrétien, unveiled a policy paper that proposed ending the special legal relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Canadian state and dismantling the Indian Act. This white paper was met with forceful opposition from Aboriginal leaders across the country and sparked a new era of Indigenous political organizing in Canada.

The federal government's intention, as described in the white paper, was to achieve equality among all Canadians by eliminating Indian as a distinct legal status and by regarding Aboriginal peoples simply as citizens with the same rights, opportunities and responsibilities as other Canadians. In keeping with Trudeau's vision of a "just society," the government proposed to repeal legislation that it considered discriminatory. In this view, the Indian Act was discriminatory because it applied only to Aboriginal peoples and not to Canadians in general. The white paper stated that removing the unique legal status established by the Indian Act would "enable the Indian people to be free -- free to develop Indian cultures in an environment of legal, social and economic equality with other Canadians."

To this end, the white paper proposed to:

- Eliminate

Indian

status

- Dissolve the Department of Indian Affairs within five

years

- Abolish the Indian Act

- Convert reserve land to private

property that can be sold by the band or its members

- Transfer

responsibility for Indian affairs from the federal government to

the province and integrate these services into those provided to

other Canadian citizens

- Provide funding for economic

development

- Appoint a commissioner to address outstanding land

claims and gradually terminate existing treaties

What Led to the White Paper?

By the 1960s, the federal government could not deny that Aboriginal peoples were facing serious socio-economic barriers, such as greater poverty and higher infant mortality rates than non-Indigenous Canadians and lower life expectancy and levels of education. The civil rights movement sweeping the United States brought public attention to the intense racism and discrimination experienced by African Americans and other minorities. The movement also led many Canadians to question inequality and discrimination in their own society, particularly the treatment of First Nations.

In 1963, the federal government commissioned University

of

British Columbia anthropologist Harry B. Hawthorn to investigate

the social conditions of Aboriginal peoples across Canada. In his

report, A Survey of the Contemporary

Indians of Canada: Economic,

Political, Educational Needs and Policies, Hawthorn concluded

that Aboriginal peoples were Canada's most disadvantaged and

marginalized population. They were "citizens minus." Hawthorn

attributed this situation to years of failed government policy,

particularly the residential school system, which left students

unprepared for participation in the contemporary economy.

Hawthorn recommended that Aboriginal peoples be considered

"citizens plus" and be provided with the opportunities and

resources to choose their own lifestyles, whether within reserve

communities or elsewhere. He also advocated ending all forced

assimilation programs, especially the residential schools.

Based on Hawthorn's recommendations, Chrétien decided to amend the Indian Act. The federal government began a national program of consultation with First Nations communities across Canada. The government distributed the informational booklet Choosing a Path to reserve communities, organized community meetings, and in May 1969 brought regional Aboriginal representatives to Ottawa for a nationwide meeting. During these consultations, First Nations representatives consistently expressed concern about Aboriginal and treaty rights, title to the land, self-determination, and access to education and health care.

In June 1969, Ottawa, in answer to the consultations,

produced their white paper proposing to dismantle Indian

Affairs.

Responses to the White Paper

Aboriginal people across Canada were shocked. The white paper failed to address the concerns raised by their leaders during the consultation process. It contained no provisions to recognize and honour First Nations' special rights, or to recognize and deal with historical grievances such as title to the land and Aboriginal and treaty rights, or to facilitate meaningful Indigenous participation in Canadian policy making.

Though the white paper acknowledged the social inequality of Aboriginal peoples in Canada and to a lesser degree the history of poor federal policy choices, many Aboriginal peoples viewed the new policy statement as the culmination of Canada's long-standing goal to assimilate Indians into mainstream Canadian society. Aboriginal groups felt that the federal government was simply, as Harold Cardinal put it, "passing the buck" to the provinces. Canada was absolving itself of its responsibility for historical injustices and of its obligation to uphold treaty rights and maintain Canada's special relationship with First Nations. First Nations were also outraged that Indigenous peoples' opinions, expressed during the consultation process, appeared to have been disregarded. Instead of amending the Indian Act, the government had decided to simply abolish it.

A forceful spokesperson was Harold Cardinal, the 24-year-old Cree man who headed up the Indian Association of Alberta. Cardinal's book The Unjust Society exposed for the non-Native public the hypocrisy of the notion that Canada was a "just society." Cardinal called the white paper "a thinly disguised programme of extermination through assimilation." He saw the white paper as a form of cultural genocide. In 1970, the Indian Association of Alberta, under Cardinal's leadership, rejected the white paper in their document Citizens Plus, which became popularly known as the Red Paper. Citizens Plus was soon adopted as the national Indian stance on the white paper. Quoting the document, Aboriginal organizations across Canada agreed: "There is nothing more important than our treaties, our lands and the well-being of our future generations."

In British Columbia, the controversy over the white paper sparked a new period of political organizing. With the white paper as focal point, First Nations across the province came together in new ways. They were spearheaded by a younger generation of leaders who, like Cardinal, were university educated and politically savvy. In November 1969, three Aboriginal leaders -- Rose Charlie of the Indian Homemakers' Association, Philip Paul of the Southern Vancouver Island Tribal Federation, and Don Moses of the North American Indian Brotherhood -- invited bands across British Columbia to a conference in Kamloops where they could develop a collective response to the white paper and discuss the ongoing fight for recognition of Aboriginal title and rights. Representatives from 140 bands attended the conference -- at that point the largest meeting ever of the province's Aboriginal leaders.

The Kamloops conference led to the formation of a new provincial organization -- the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) -- whose main focus was the resolution of land claims. The UBCIC's A Declaration of Indian Rights: The B.C. Indian Position Paper, or "Brown Paper," of 1970 rejected the 1969 white paper's proposals and asserted that Aboriginal peoples continued to hold Aboriginal title to the land. The Brown Paper would become the cornerstone of UBCIC's policy.

Recommended Resources

Canada, Indian and

Northern

Affairs. Statement of the Government

of Canada on Indian Policy.

Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, 1969.

Available online: here

Cairns, Alan. Citizens Plus: Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian State. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000.

Tennant, Paul. Aboriginal Peoples and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1990.

Turner, Dale. This is Not a Peace Pipe: Towards a Critical Indigenous Philosophy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Weaver, Sally M. Making Canadian Indian Policy: The Hidden Agenda 1968-1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981.

Responses to the White Paper

Cardinal, Harold. The Unjust Society. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1999.

Indian Association of Alberta. Citizens Plus. ("The Red Paper") Edmonton: Indian Association of Alberta, 1970.

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, A Declaration of Indian Rights: The B.C. Indian Position Paper. Vancouver: UBCIC, 1970.

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. "Our History."

The Hawthorn Report

Hawthorn, Harry, ed. A Survey of the Contemporary

Indians of

Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies. 2

vols. Ottawa: Queen's Printer Press, 1966-1967. Available online here.

Weaver, Sally. "The Hawthorn Report: Its Use in the Making of Canadian Indian Policy." In Anthropology, Public Policy and Native Peoples in Canada, edited by Noel Dyck and James B. Waldram. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993. 75-97.

(Source: indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca)

Statement of the Government of Canada on

Indian Policy (The

White Paper, 1969)

Table of Contents

Statement of the

Government of Canada on Indian Policy

(The White Paper,

1969)

Presented to the First Session of the Twenty-eighth Parliament by the Honourable Jean Chrétien, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development

To be an Indian is to be a man, with all a man's needs and abilities. To be an Indian is also to be different. It is to speak different languages, draw different pictures, tell different tales and to rely on a set of values developed in a different world.

Canada is richer for its Indian component, although there have been times when diversity seemed of little value to many Canadians.

But to be a Canadian Indian today is to be someone different in another way. It is to be someone apart -- apart in law, apart in the provision of government services and, too often, apart in social contacts.

To be an Indian is to lack power -- the power to act as owner of your lands, the power to spend your own money and, too often, the power to change your own condition.

Not always, but too often, to be an Indian is to be without -- without a job, a good house, or running water; without knowledge, training or technical skill and, above all, without those feelings of dignity and self-confidence that a man must have if he is to walk with his head held high.

All these conditions of the Indians are the product of history and have nothing to do with their abilities and capacities. Indian relations with other Canadians began with special treatment by government and society, and special treatment has been the rule since Europeans first settled in Canada. Special treatment has made of the Indians a community disadvantaged and apart.

Obviously, the course of history must be changed.

To be an Indian must be to be free -- free to develop Indian cultures in an environment of legal, social and economic equality with other Canadians.

Foreword

The Government believes that its policies must lead to the full, free and nondiscriminatory participation of the Indian people in Canadian society. Such a goal requires a break with the past. It requires that the Indian people's role of dependence be replaced by a role of equal status, opportunity and responsibility, a role they can share with all other Canadians.

This proposal is a recognition of the necessity made plain in a year's intensive discussions with Indian people throughout Canada. The Government believes that to continue its past course of action would not serve the interests of either the Indian people or their fellow Canadians.

The policies proposed recognize the simple reality that the separate legal status of Indians and the policies which have flowed from it have kept the Indian people apart from and behind other Canadians. The Indian people have not been full citizens of the communities and provinces in which they live and have not enjoyed the equality and benefits that such participation offers.

The treatment resulting from their different status has been often worse, sometimes equal and occasionally better than that accorded to their fellow citizens. What matters is that it has been different.

Many Indians, both in isolated communities and in cities, suffer from poverty. The discrimination which affects the poor, Indian and non-Indian alike, when compounded with a legal status that sets the Indian apart, provides dangerously fertile ground for social and cultural discrimination.

In recent years there has been a rapid increase in the Indian population. Their health and education levels have improved. There has been a corresponding rise in expectations that the structure of separate treatment cannot meet.

A forceful and articulate Indian leadership has developed to express the aspirations and needs of the Indian community. Given the opportunity, the Indian people can realize an immense human and cultural potential that will enhance their own well-being, that of the regions in which they live and of Canada as a whole. Faced with a continuation of past policies, they will unite only in a common frustration.

The Government does not wish to perpetuate policies which carry with them the seeds of disharmony and disunity, policies which prevent Canadians from fulfilling themselves and contributing to their society. It seeks a partnership to achieve a better goal. The partners in this search are the Indian people, the governments of the provinces, the Canadian community as a whole and the Government of Canada. As all partnerships do, this will require consultation, negotiation, give and take, and co-operation if it is to succeed.

Many years will be needed. Some efforts may fail, but learning comes from failure and from what is learned success may follow. All the partners have to learn; all will have to change many attitudes.

Governments can set examples, but they cannot change the hearts of men. Canadians, Indians and non-Indians alike stand at the crossroads. For Canadian society the issue is whether a growing element of its population will become full participants contributing in a positive way to the general well-being or whether, conversely, the present social and economic gap will lead to their increasing frustration and isolation, a threat to the general well-being of society. For many Indian people, one road does exist, the only road that has existed since Confederation and before, the road of different status, a road which has led to a blind alley of deprivation and frustration. This road, because it is a separate road, cannot lead to full participation, to equality in practice as well as in theory. In the pages which follow, the Government has outlined a number of measures and a policy which it is convinced will offer another road for Indians, a road that would lead gradually away from different status to full social, economic and political participation in Canadian life. This is the choice.

Indian people must be persuaded, must persuade themselves, that this path will lead them to a fuller and richer life.

Canadian society as a whole will have to recognize the need for changed attitudes and a truly open society. Canadians should recognize the dangers of failing to strike down the barriers which frustrate Indian people. If Indian people are to become full members of Canadian society they must be warmly welcomed by that society.

The Government commends this policy for the consideration of all Canadians, Indians and non-Indians, and all governments in Canada.

Summary

1 Background

The Government has reviewed its programs for Indians and has considered the effects of them on the present situation of the Indian people. The review has drawn on extensive consultations with the Indian people, and on the knowledge and experience of many people both in and out of government.

This review was a response to things said by the Indian people at the consultation meetings which began a year ago and culminated in a meeting in Ottawa in April.

This review has shown that this is the right time to change long-standing policies. The Indian people have shown their determination that present conditions shall not persist.

Opportunities are present today in Canadian society and new directions are open. The Government believes that Indian people must not be shut out of Canadian life and must share equally in these opportunities.

The Government could press on with the policy of fostering further education; could go ahead with physical improvement programs now operating in reserve communities; could press forward in the directions of recent years, and eventually many of the problems would be solved. But progress would be too slow. The change in Canadian society in recent years has been too great and continues too rapidly for this to be the answer. Something more is needed. We can no longer perpetuate the separation of Canadians. Now is the time to change.

This Government believes in equality. It believes that all men and women have equal rights. It is determined that all shall be treated fairly and that no one shall be shut out of Canadian life, and especially that no one shall be shut out because of his race.

This belief is the basis for the Government's determination to open the doors of opportunity to all Canadians, to remove the barriers which impede the development of people, of regions and of the country.

Only a policy based on this belief can enable the Indian people to realize their needs and aspirations.

The Indian people are entitled to such a policy. They are entitled to an equality which preserves and enriches Indian identity and distinction; an equality which stresses Indian participation in its creation and which manifests itself in all aspects of Indian life.

The goals of the Indian people cannot be set by others; they must spring from the Indian community itself -- but government can create a framework within which all persons and groups can seek their own goals.

2 The New Policy

True equality presupposes that the Indian people have the right to full and equal participation in the cultural, social, economic and political life of Canada.

The government believes that the framework within which individual Indians and bands could achieve full participation requires:

- that the legislative and constitutional bases of discrimination be removed;

- that there be positive recognition by everyone of the unique contribution of Indian culture to Canadian life;

- that services come through the same channels and from the same government agencies for all Canadians;

- that those who are furthest behind be helped most;

- that lawful obligations be recognized;

- that control of Indian lands be transferred to the Indian people.

The Government would be prepared to take the following steps to create this framework:

- Propose to Parliament that the Indian Act be repealed and take such legislative steps as may be necessary to enable Indians to control Indian lands and to acquire title to them.

- Propose to the governments of the provinces that they take over the same responsibility for Indians that they have for other citizens in their provinces. The take-over would be accompanied by the transfer to the provinces of federal funds normally provided for Indian programs, augmented as may be necessary.

- Make substantial funds available for Indian economic development as an interim measure.

- Wind up that part of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development which deals with Indian Affairs. The residual responsibilities of the Federal Government for programs in the field of Indian affairs would be transferred to other appropriate federal departments.

In addition, the Government will appoint a Commissioner to consult with the Indians and to study and recommend acceptable procedures for the adjudication of claims.

The new policy looks to a better future for all Indian people wherever they may be. The measures for implementation are straightforward. They require discussion, consultation and negotiation with the Indian people -- individuals, bands and associations and with provincial governments.

Success will depend upon the co-operation and assistance of the Indians and the provinces. The Government seeks this cooperation and will respond when it is offered.

3 The Immediate Steps

Some changes could take place quickly. Others would take longer. It is expected that within five years the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development would cease to operate in the field of Indian affairs; the new laws would be in effect and existing programs would have been devolved. The Indian lands would require special attention for some time. The process of transferring control to the Indian people would be under continuous review.

The Government believes this is a policy which is just and necessary. It can only be successful if it has the support of the Indian people, the provinces, and all Canadians.

The policy promises all Indian people a new opportunity to expand and develop their identity within the framework of a Canadian society which offers them the rewards and responsibilities of participation, the benefits of involvement and the pride of belonging.

Historical Background

The weight of history affects us all, but it presses most heavily on the Indian people. Because of history, Indians today are the subject of legal discrimination; they have grievances because of past undertakings that have been broken or misunderstood; they do not have full control of their lands; and a higher proportion of Indians than other Canadians suffer poverty in all its debilitating forms. Because of history too, Indians look to a special department of the Federal Government for many of the services that other Canadians get from provincial or local governments.

This burden of separation has its origin deep in Canada's past and in early French and British colonial policy. The elements which grew to weigh so heavily were deeply entrenched at the time of Confederation.

Before that time there had evolved a policy of entering into agreements with the Indians, of encouraging them to settle on reserves held by the Crown for their use and benefit, and of dealing with Indian lands through a separate organization a policy of treating Indian people as a race apart.

After Confederation, these well-established precedents were followed and expanded. Exclusive legislative authority was given the Parliament of Canada in relation to "Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians" under Head 24 of Section 91 of the British North America Act. Special legislation -- an Indian Act -- was passed, new treaties were entered into, and a network of administrative offices spread across the country either in advance of or along with the tide of settlement.

This system -- special legislation, a special land system and separate administration for the Indian people -- continues to be the basis of present Indian policy. It has saved for the Indian people places they can call home, but has carried with it serious human and physical as well as administrative disabilities.

Because the system was in the hands of the Federal Government, the Indians did not participate in the growth of provincial and local services. They were not required to participate in the development of their own communities which were tax exempt. The result was that the Indians persuaded that property taxes were an unnecessary element in their lives, did not develop services for themselves. For many years such simple and limited services as were required to sustain life were provided through a network of Indian agencies reflecting the authoritarian tradition of a colonial administration, and until recently these agencies had staff and funds to do little more than meet the most severe cases of hardship and distress.

The tradition of federal responsibility for Indian matters inhibited the development of a proper relationship between the provinces and the Indian people as citizens. Most provinces, faced with their own problems of growth and change, left responsibility for their Indian residents to the Federal Government. Indeed, successive Federal Governments did little to change the pattern. The result was that Indians were the almost exclusive concern of one agency of the Federal Government for nearly a century.

For a long time the problems of physical, legal and administrative separation attracted little attention. The Indian people were scattered in small groups across the country, often in remote areas. When they were in contact with the new settlers, there was little difference between the living standards of the two groups.

Initially, settlers as well as Indians depended on game, fish and fur. The settlers, however, were more concerned with clearing land and establishing themselves and differences soon began to appear.

With the technological change of the twentieth century, society became increasingly industrial and complex, and the separateness of the Indian people became more evident. Most Canadians moved to the growing cities, but the Indians remained largely a rural people, lacking both education and opportunity. The land was being developed rapidly, but many reserves were located in places where little development was possible. Reserves were usually excluded from development and many began to stand out as islands of poverty. The policy of separation had become a burden.

The legal and administrative discrimination in the treatment of Indian people has not given them an equal chance of success. It has exposed them to discrimination in the broadest and worst sense of the term a discrimination that has profoundly affected their confidence that success can be theirs. Discrimination breeds discrimination by example, and the separateness of Indian people has affected the attitudes of other Canadians towards them.

The system of separate legislation and administration has also separated people of Indian ancestry into three groups -- registered Indians, who are further divided into those who are under treaty and those who are not; enfranchised Indians who lost, or voluntarily relinquished, their legal status as Indians; and the Métis, who are of Indian ancestry but never had the status of registered Indians.

The Case for the New Policy

In the past ten years or so, there have been important improvements in education, health, housing, welfare and community development. Developments in leadership among the Indian communities have become increasingly evident. Indian people have begun to forge a new unity. The Government believes progress can come from these developments but only if they are met by new responses. The proposed policy is a new response.

The policy rests upon the fundamental right of Indian people to full and equal participation in the cultural, social, economic and political life of Canada.

To argue against this right is to argue for discrimination, isolation and separation. No Canadian should be excluded from participation in community life, and none should expect to withdraw and still enjoy the benefits that flow to those who participate.

1 The Legal Structure

Legislative and constitutional bases of discrimination must be removed.

Canada cannot seek the just society and keep discriminatory legislation on its statute books. The Government believes this to be self-evident. The ultimate aim of removing the specific references to Indians from the constitution may take some time, but it is a goal to be kept constantly in view. In the meantime, barriers created by special legislation can generally be struck down.

Under the authority of Head 24, Section 91 of the British North America Act, the Parliament of Canada has enacted the Indian Act. Various federal-provincial agreements and some other statutes also affect Indian policies.

In the long term, removal of the reference in the constitution would be necessary to end the legal distinction between Indians and other Canadians. In the short term, repeal of the Indian Act and enactment of transitional legislation to ensure the orderly management of Indian land would do much to mitigate the problem.

The ultimate goal could not be achieved quickly, for it requires a change in the economic circumstances of the Indian people and much preliminary adjustment with provincial authorities. Until the Indian people are satisfied that their land holdings are solely within their control, there may have to be some special legislation for Indian lands.

2 The Indian Cultural Heritage

There must be positive recognition by everyone of the unique contribution of Indian culture to Canadian society.

It is important that Canadians recognize and give credit to the Indian contribution. It manifests itself in many ways; yet it goes largely unrecognized and unacknowledged. Without recognition by others it is not easy to be proud.

All of us seek a basis for pride in our own lives, in those of our families and of our ancestors. Man needs such pride to sustain him in the inevitable hour of discouragement, in the moment when he faces obstacles, whenever life seems turned against him. Everyone has such moments. We manifest our pride in many ways, but always it supports and sustains us. The legitimate pride of the Indian people has been crushed too many times by too many of their fellow Canadians. The principle of equality and all that goes with it demands that all of us recognize each other's cultural heritage as a source of personal strength.

Canada has changed greatly since the first Indian Act was passed. Today it is made up of many people with many cultures. Each has its own manner of relating to the other; each makes its own adjustments to the larger society.

Successful adjustment requires that the larger groups accept every group with its distinctive traits without prejudice, and that all groups share equitably in the material and non-material wealth of the country.

For many years Canadians believed the Indian people had but two choices: they could live in a reserve community, or they could be assimilated and lose their Indian identity. Today Canada has more to offer. There is a third choice -- a full role in Canadian society and in the economy while retaining, strengthening and developing an Indian identity which preserves the good things of the past and helps Indian people to prosper and thrive.

This choice offers great hope for the Indian people. It offers great opportunity for Canadians to demonstrate that in our open society there is room for the development of people who preserve their different cultures and take pride in their diversity.

This new opportunity to enrich Canadian life is central to the Government's new policy. If the policy is to be successful, the Indian people must be in a position to play a full role in Canada's diversified society, a role which stresses the value of their experience and the possibilities of the future.

The Indian contribution to North American society is often overlooked, even by the Indian people themselves. Their history and tradition can be a rich source of pride, but are not sufficiently known and recognized. Too often, the art forms which express the past are preserved, but are inaccessible to most Indian people. This richness can be shared by all Canadians. Indian people must be helped to become aware of their history and heritage in all its forms, and this heritage must be brought before all Canadians in all its rich diversity.

Indian culture also lives through Indian speech and thought. The Indian languages are unique and valuable assets. Recognizing their value is not a matter of preserving ancient ways as fossils, but of ensuring the continuity of a people by encouraging and assisting them to work at the continuing development of their inheritance in the context of the present-day world. Culture lives and develops in the daily life of people, in their communities and in their other associations, and the Indian culture can be preserved, perpetuated and developed only by the Indian people themselves.

The Indian people have often been made to feel that their culture and history are not worthwhile. To lose a sense of worthiness is damaging. Success in life, in adapting to change, and in developing appropriate relations within the community as well as in relation to a wider world, requires a strong sense of personal worth -- a real sense of identity.

Rich in folklore, in art forms and in concepts of community life, the Indian cultural heritage can grow and expand further to enrich the general society. Such a development is essential if the Indian people are again to establish a meaningful sense of identity and purpose and if Canada is to realize its maximum potential.

The Government recognizes that people of Indian ancestry must be helped in new ways in this task. It proposes, through the Secretary of State, to support associations and groups in developing a greater appreciation of their cultural heritage. It wants to foster adequate communication among all people of Indian descent and between them and the Canadian community as a whole.

Steps will be taken to enlist the support of Canadians generally. The provincial governments will be approached to support this goal through their many agencies operating in the field Provincial educational authorities will be urged to intensify their review of school curriculae and course content with a view to ensuring that they adequately reflect Indian culture and Indian contributions to Canadian development.

3 Programs and Services

Services must come through the same channels and from the same government agencies for all Canadians.

This is an undeniable part of equality. It has been shown many times that separation of people follows from separate services. There can be no argument about the principle of common services. It is right.

It cannot be accepted now that Indians should be constitutionally excluded from the right to be treated within their province as full and equal citizens, with all the responsibilities and all the privileges that this might entail. It is in the provincial sphere where social remedies are structured and applied, and the Indian people, by and large, have been non-participating members of provincial society.

Canadians receive a wide range of services through provincial and local governments, but the Indian people and their communities are mostly outside that framework. It is no longer acceptable that the Indian people should be outside and apart. The Government believes that services should be available on an equitable basis, except for temporary differentiation based on need. Services ought not to flow from separate agencies established to serve particular groups, especially not to groups that are identified ethnically.

Separate but equal services do not provide truly equal treatment. Treatment has not been equal in the case of Indians and their communities. Many services require a wide range of facilities which cannot be duplicated by separate agencies. Others must be integral to the complex systems of community and regional life and cannot be matched on a small scale.

The Government is therefore convinced that the traditional method of providing separate services to Indians must be ended. All Indians should have access to all programs and services of all levels of government equally with other Canadians.

The Government proposes to negotiate with the provinces and conclude agreements under which Indian people would participate in and be served by the full programs of the provincial and local systems. Equitable financial arrangements would be sought to ensure that services could be provided in full measure commensurate with the needs. The negotiations must seek agreements to end discrimination while ensuring that no harm is inadvertently done to Indian interests. The Government further proposes that federal disbursements for Indian programs in each province be transferred to that province. Subject to negotiations with the provinces, such provisions would as a matter of principle eventually decline, the provinces ultimately assuming the same responsibility for services to Indian residents as they do for services to others.

At the same time, the Government proposes to transfer all remaining federal responsibilities for Indians from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development to other departments, including the Departments of Regional Economic Expansion, Secretary of State, and Manpower and Immigration.

It is important that such transfers take place without disrupting services and that special arrangements not be compromised while they are subject to consultation and negotiation. The Government will pay particular attention to this.

4 Enriched Services

Those who are furthest behind must be helped most.

There can be little argument that conditions for many Indian people are not satisfactory to them and are not acceptable to others. There can be little question that special services, and especially enriched services, will be needed for some time.

Equality before the law and in programs and services does not necessarily result in equality in social and economic conditions. For that reason, existing programs will be reviewed. The Department of Regional Economic Expansion, the Department of Manpower and Immigration, and other federal departments involved would be prepared to evolve programs that would help break past patterns of deprivation.

Additional funds would be available from a number of different sources. In an atmosphere of greater freedom, those who are able to do so would be expected to help themselves, so more funds would be available to help those who really need it. The transfer of Indian lands to Indian control should enable many individuals and groups to move ahead on their own initiative. This in turn would free funds for further enrichment of programs to help those who are furthest behind. By ending some programs and replacing them with others evolved within the community, a more effective use of funds would be achieved. Administrative savings would result from the elimination of separate agencies as various levels of government bring general programs and resources to bear. By broadening the base of service agencies, this enrichment could be extended to all who need it. By involving more agencies working at different levels, and by providing those agencies with the means to make them more effective, the Government believes that root problems could be attacked, that solutions could be found that hitherto evaded the best efforts and best-directed of programs.

The economic base for many Indians is their reserve land, but the development of reserves has lagged.

Among the many factors that determine economic growth of reserves, their location and size are particularly important. There are a number of reserves located within or near growing industrial areas which could provide substantial employment and income to their owners if they were properly developed. There are other reserves in agricultural areas which could provide a livelihood for a larger number of family units than is presently the case. The majority of the reserves, however, are located in the boreal or wooded regions of Canada, most of them geographically isolated and many having little economic potential. In these areas, low income, unemployment and under-employment are characteristic of Indians and non-Indians alike.

Even where reserves have economic potential, the Indians have been handicapped. Private investors have been reluctant to supply capital for projects on land which cannot be pledged as security. Adequate social and risk capital has not been available from public sources. Most Indians have not had the opportunity to acquire managerial experience, nor have they been offered sufficient technical assistance.

The Government believes that the Indian people should have the opportunity to develop the resources of their reserves so they may contribute to their own well-being and the economy of the nation. To develop Indian reserves to the level of the regions in which they are located will require considerable capital over a period of some years, as well as the provision of managerial and technical advice. Thus the Government believes that all programs and advisory services of the federal and provincial governments should be made readily available to Indians.

In addition, and as an interim measure, the Government proposes to make substantial additional funds available for investment in the economic progress of the Indian people. This would overcome the barriers to early development of Indian lands and resources, help bring Indians into a closer working relationship with the business community, help finance their adjustment to new employment opportunities, and facilitate access to normal financial sources.

Even if the resources of Indian reserves are fully utilized, however, they cannot all properly support their present Indian populations, much less the populations of the future. Many Indians will, as they are now doing, seek employment elsewhere as a means of solving their economic problems. Jobs are vital and the Government intends that the full counselling, occupational training and placement resources of the Department of Manpower and Immigration are used to further employment opportunities for Indians. The government will encourage private employers to provide opportunities for the Indian people.

In many situations, the problems of Indians are similar to those faced by their non-Indian neighbours. Solutions to their problems cannot be found in isolation but must be sought within the context of regional development plans involving all the people. The consequence of an integrated regional approach is that all levels of government federal, provincial and local -- and the people themselves are involved. Helping overcome regional disparities in the economic well-being of Canadians is the main task assigned to the Department of Regional Economic Expansion. The Government believes that the needs of Indian communities should be met within this framework.

5 Claims and Treaties

Lawful obligations must be recognized

Many of the Indian people feel that successive governments have not dealt with them as fairly as they should. They believe that lands have been taken from them in an improper manner, or without adequate compensation, that their funds have been improperly administered, that their treaty rights have been breached. Their sense of grievance influences their relations with governments and the community and limits their participation in Canadian life.

Many Indians look upon their treaties as the source of their rights to land, to hunting and fishing privileges, and to other benefits. Some believe the treaties should be interpreted to encompass wider services and privileges, and many believe the treaties have not been honoured. Whether or not this is correct in some or many cases, the fact is the treaties affect only half the Indians of Canada. Most of the Indians of Quebec, British Columbia, and the Yukon are not parties to a treaty.

The terms and effects of the treaties between the Indian people and the Government are widely misunderstood. A plain reading of the words used in the treaties reveals the limited and minimal promises which were included in them. As a result of the treaties, some Indians were given an initial cash payment and were promised land reserved for their exclusive use, annuities, protection of hunting, fishing and trapping privileges subject (in most cases) to regulation, a school or teachers in most instances and, in one treaty only, a medicine chest.

There were some other minor considerations, such as the annual provision of twine and ammunition.

The annuities have been paid regularly. The basic promise to set aside reserve land has been kept except in respect of the Indians of the Northwest Territories and a few bands in the northern parts of the Prairie Provinces. These Indians did not choose land when treaties were signed. The government wishes to see these obligations dealt with as soon as possible.

The right to hunt and fish for food is extended unevenly across the country and not always in relation to need. Although game and fish will become less and less important for survival as the pattern of Indian life continues to change, there are those who, at this time, still live in the traditional manner that their forefathers lived in when they entered into treaty with the government. The Government is prepared to allow such persons transitional freer hunting of migratory birds under the Migratory Birds Convention Act and Regulations.

The significance of the treaties in meeting the economic, educational, health and welfare needs of the Indian people has always been limited and will continue to decline. The services that have been provided go far beyond what could have been foreseen by those who signed the treaties.

The Government and the Indian people must reach a common understanding of the future role of the treaties. Some provisions will be found to have been discharged; others will have continuing importance. Many of the provisions and practices of another century may be considered irrelevant in light of a rapidly changing society and still others may be ended by mutual agreement. Finally, once Indian lands are securely within Indian control, the anomaly of treaties between groups within society and the government of that society will require that these treaties be reviewed to -- how they can be equitably ended.

Other grievances have been asserted in more general terms. It is possible that some of these can be verified by appropriate research and may be susceptible of specific remedies. Others relate to aboriginal claims to land. These are so general and undefined it is not realistic to think of them as specific claims capable of remedy except through a policy and program that will end injustice to Indians as members of the Canadian community. This is the policy that the Government is proposing for discussion.

At the recent consultation meeting in Ottawa representatives of the Indians, chosen at each of the earlier regional meetings, expressed concern about the extent of their knowledge of Indian rights and treaties. They indicated a desire to undertake further research to establish their rights with greater precision, elected a National Committee on Indian Rights and Treaties for this purpose and sought government financial support for research.

The Government had intended to introduce legislation to establish an Indian Claims Commission to hear and determine Indian claims. Consideration of the questions raised at the consultations and the review of Indian policy have raised serious doubts as to whether a Claims Commission as proposed to Parliament in 1965 is the right way to deal with the grievances of Indians put forward as claims.

The Government has concluded that further study and research are required by both the Indians and the Government. It will appoint a Commissioner who, in consultation with representatives of the Indians, will inquire into and report upon how claims arising in respect of the performance of the terms of treaties and agreements formally entered into by representatives of the Indians and the Crown, and the administration of moneys and lands pursuant to schemes established by legislation for the benefit of Indians may be adjudicated.

The Commissioner will also classify the claims that in his judgment ought to be referred to the courts or any special quasijudicial body that may be recommended.

It is expected that the Commissioner's inquiry will go on concurrently with that of the National Indian Committee on Indian Rights and Treaties and the Commissioner will be authorized to recommend appropriate support to the Committee so that it may conduct research on the Indians' behalf and assist the Commissioner in his inquiry.

6 Indian Lands

Control of Indian lands should be transferred to the Indian people.

Frustration is as great a handicap as a sense of grievance. True co-operation and participation can come only when the Indian people are controlling the land which makes up the reserves.

The reserve system has provided the Indian people with lands that generally have been protected against alienation without their consent. Widely scattered across Canada, the reserves total nearly 6,000,000 acres and are divided into about 2,200 parcels of varying sizes. Under the existing system, title to reserve lands is held either by the Crown in right of Canada or the Crown in right of one of the provinces. Administrative control and legislative authority are, however, vested exclusively in the Government and the Parliament of Canada. It is a trust. As long as this trust exists, the Government, as a trustee, must supervise the business connected with the land.

The result of Crown ownership and the Indian Act has been to tie the Indian people to a land system that lacks flexibility and inhibits development. If an Indian band wishes to gain income by leasing its land, it has to do so through a cumbersome system involving the Government as trustee. It cannot mortgage reserve land to finance development on its own initiative. Indian people do not have control of their lands except as the Government allows and this is no longer acceptable to them. The Indians have made this clear at the consultation meetings. They now want real control, and this Government believes that they should have it. The Government recognizes that full and true equality calls for Indian control and ownership of reserve land.

Between the present system and the full holding of title in fee simple lie a number of intermediate states. The first step is to change the system under which ministerial decision is required for all that is done with Indian land. This is where the delays, the frustrations and the obstructions lie. The Indians must control their land. This can be done in many ways. The Government believes that each band must make its own decision as to the way it wants to take control of its land and the manner in which it intends to manage it. It will take some years to complete the process of devolution.

The Government believes that full ownership implies many things. It carries with it the free choice of use, of retention or of disposition. In our society it also carries with it an obligation to pay for certain services. The Government recognizes that it may not be acceptable to put all lands into the provincial systems immediately and make them subject to taxes. When the Indian people see that the only way they can own and fully control land is to accept taxation the way other Canadians do, they will make that decision.

Alternative methods for the control of their lands will be made available to Indian individuals and bands. Whatever methods of land control are chosen by the Indian people, the present system under which the Government must execute all leases, supervise and control procedures and surrenders, and generally act as trustee, must be brought to an end. But the Indian land heritage should be protected. Land should be alienated from them only by the consent of the Indian people themselves. Under a proposed Indian Lands Act full management would be in the hands of the bands and, if the bands wish, they or individuals would be able to take title to their land without restrictions.

As long as the Crown controls the land for the benefit of bands who use and occupy it, it is responsible for determining who may, as a member of a band, share in the assets of band land. The qualifications for band membership which it has imposed are part of the legislation -- the Indian Act governing the administration of reserve lands. Under the present Act, the Government applies and interprets these qualifications. When bands take title to their lands, they will be able to define and apply these qualifications themselves.

The Government is prepared to transfer to the Indian people the reserve lands, full control over them and, subject to the proposed Indian Lands Act, the right to determine who shares in ownership. The Government proposes to seek agreements with the bands and, where necessary, with the governments of the provinces. Discussions will be initiated with the Indian people and the provinces to this end.

Implementation of the New Policy

1 Indian Associations and Consultation

Successful implementation of the new policy would require the further development of a close working relationship with the Indian community. This was made abundantly clear in the proposals set forth by the National Indian Brotherhood at the national meeting to consult on revising the Indian Act. Their brief succinctly identified the needs at that time and offers a basis for discussing the means of adaptation to the new policy.

To this end the Government proposes to invite the executives of the National Indian Brotherhood and the various provincial associations to discuss the role they might play in the implementation of the new policy, and the financial resources they may require. The Government recognizes their need for independent advice, especially on legal matters. The Government also recognizes that the discussions will place a heavy burden on Indian leaders during the adjustment period. Special arrangements will have to be made so that they may take the time needed to meet and discuss all aspects of the new policy and its implementation.

Needs and conditions vary greatly from province to province, since the adjustments would be different in each case, the bulk of the negotiations would likely be with the provincial bodies, regional groups and the bands themselves. There are those matters which are of concern to all, and the National Indian Brotherhood would be asked to act in liaison with the various provincial associations and with the federal departments which would have ongoing responsibilities.

The Government proposes to ask the associations act as the principal agencies through which consultation and negotiations would he conducted, but each band would be consulted about gaining ownership of its land holdings. Bands would be asked to designate the association through which their broad interests would be represented.

2 Transitional Period

The Government hopes to have the bulk of the policy in effect within five years and believes that the necessary financial and other arrangements can be concluded so that Indians will have full access to provincial services within that time. It will seek an immediate start to the many discussions that will need to be held with the provinces and with representatives of the Indian people.

The role of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development in serving the Indian people would be phased out as arrangements with the provinces were completed and remaining Federal Government responsibilities transferred to other departments.

The Commissioner will be appointed soon and instructed to get on with his work.

Steps would be taken in consultation with representatives of the Indian people to transfer control of land to them. Because of the need to consult over five hundred bands the process would take some time.

A policy can never provide the ultimate solutions to

all

problems. A policy can achieve no more than is desired by the

people it is intended to serve. The essential role of the

Government's proposed new policy for Indians is that it

acknowledges that truth by recognizing the central and essential

role of the Indian people in solving their own problems. It will

provide for first time, a non-discriminatory framework within

which, in an atmosphere of freedom, the Indian people could, with

other Canadians, work out their own destiny.

(Published under the authority of the Honourable Jean Chrétien, PC, MP Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Ottawa, 1969 Queen's Printer Cat. No. R32-2469.)

Sir John A. MacDonald's Reign of Terror

On the eve of official celebrations of Canadian Confederation 150 years ago, on June 21 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a big gesture to show how committed he is to righting historical wrongs committed against Canada's original peoples. He changed the name of the building in which his government office is located on Wellington street in Ottawa, across from the Parliament of Canada so that it would no longer be known as the Langevin Block. Canadians are told that Hector-Louis Langevin, was a "lesser father of Confederation" and the architect of the genocidal Residential School System.

It is high time all names of those heroes of British colonialism and the ruling class who committed crimes against the peoples be removed and replaced with names of actual heroes of the people, decided by the people. But Trudeau's gesture is suspect, proving hollow indeed because he does not want to countenance the removal of other names from all public buildings and streets beginning with that of John A. MacDonald who was by no means a "lesser father of Confederation" and, on the contrary, along with Georges-Étienne Cartier, one of the two most prominent. Most importantly, MacDonald was himself a most ardent architect of genocide.

In May 1883, John A. MacDonald laid out the aim of the residential schools in the House of Commons. He declared:

"When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write [T]he Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men."[1]

On January 3, 1887 John A. MacDonald declared one of the goals of Confederation to be to extinguish the Indigenous peoples:

"The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and to assimilate Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion, as speedily as they are fit for the change."[2]

MacDonald was also the person who arranged for the massacre of the Métis people in the territories which later became Manitoba and Saskatchewan and organized to have their leader Louis Riel hanged as a traitor. In 1870 he sent the military expedition of 1,200 under the command of the British Army Colonel Garnet Wolseley to crush the Métis' uprising in Manitoba led by Louis Riel. The newspapers in Red River, Montreal, Toronto, New York and St. Paul labelled the violent behaviour of the Expeditionary Force sent by MacDonald -- the same which later became the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) -- as a "reign of terror."[3] This represented a response to the colonial project that sought to reproduce the British state in North America and block the legitimate aspirations of the nations and peoples that comprised Canada.

The spirit that motivated Riel and the members of the provisional government at the time is contained in the Declaration of the Inhabitants of Rupert's Land and the Northwest that affirms the sovereignty of the Métis over their lands. Besides other things, they refused to recognize the authority of Canada, "[...], which presumes to have the right to come and impose on us a form of government even more incompatible with our rights and our interests [...]."

In parallel, the Hudson's Bay Company agreed to sell Rupert's Land in Canada to Great Britain for £300,000 [$1,500,000] in cash in 1869 while retaining 1/20 of the territory's fertile land to sell to settlers itself and kept all of its trading posts. Great Britain in turn allowed the Dominion of Canada to annex Rupert's Land and the North-Western territory, bringing the Hudson's Bay Company land under the jurisdiction of the new state. It formally declared them part of the Dominion of Canada. The new colonial state replaced the Hudson's Bay Company with the direct annexation of the West, the absentee-owned land. Rupert's Land was five times the size of the four colonies comprising the new Confederation.

In the 1870s and 1880s federal policy served the interests of big capital and the Canadian Pacific Railway -- led by Lord Strathcona (Donald Alexander Smith) of the Hudson's Bay Company, and such British banks as Baring Brothers -- for whom the 1867 Confederation was a nation-building project to create new markets through expansion of the state by armed conquest of traditional Indigenous territories.

On February 5, 1873, the Charter of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company was signed by the Governor General. Its provisions pledged the CPR to build the railway within ten years from July 20, 1871, in consideration of which it was to receive a land grant of 50,000,000 acres, and a subsidy of $30,000,000 payable from time to time in installments. The Company was allowed a capital of $10,000,000. Its founder was Sir Hugh Allan who is described as "one of the most conspicuous men of capital of his time and as the founder of one of the largest and at present most powerful Canadian fortunes." To achieve this Sir Georges Etienne Cartier -- yet another father of Confederation -- wrote the following "private and confidential" letter to Allan on July 30, 1872:

"The friends of the Government will expect to be assisted with funds in the pending elections, and any amount which you or your Company shall advance for that purpose shall be recouped to you. A memorandum of immediate requirements is below." This memorandum read:

"NOW WANTED.

"Sir John A. Macdonald .............. $25,000

Hon. Mr. Langevin ..................... 15,000

Sir. G.E.C. ........................... 20,000

Sir J.A. (add.) ....................... 10,000

Hon. Mr. Langevin .................... 100,000

Sir G.E.C. ............................ 30,000."

On August 7, 1872, Allan wrote, "I have already paid away about $250,000, and will have to pay at least $50,000 before the end of the month. I don't know as even that will finish it, but hope so."[4] The "great bribery scheme" engineered by Sir Hugh Allan had now reached the point where it was considered that the machinery of government was "properly fixed."

Much of the bank capital was provided by Baring Brothers, financial agents for Canada in London, founded 1810 with origins back to 1720, as investments it received from human trafficking in the Atlantic slave trade from which it derived enormous profits. It owned numerous plantations in St. Kitts and in British Guiana, for which they received some ten million pounds in "compensation" from the British state in 1839 as part of the abolition of chattel slavery. Baring Brothers financed one quarter of all U.S. railroad construction.[5] Today the Hudson's Bay Company ("the Bay") is owned by U.S. venture capitalists. Today federal policy on Indigenous peoples serves the mainly U.S. resource monopolies and the creation of a Fortress North America to defend U.S. "homeland security" and hegemonism over the entire world.

Notes

1. House of Commons [Commons Debates]. (1883, May 9). Cited in: Official report of the debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada (Vol. xiv). Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co.

2. Sir John A. Macdonald, 1887 cited by J.R. Miller, in Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens, 1989, p. 189

3. The Reign of Terror Against the Métis of Red River

4. Gustavus Myers, History of Canadian Wealth, 1913. (Sir G.E.C. refers to Cartier).

5. Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership, UCL Department of History, London.

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca

It is Canada's image which

concerned the Prime Minister when he spoke at the UN in the

General Debate on September 21. Posturing as a senior statesman even

though he has barely been in office for two years, Trudeau said: "In

conversations over the years, when I've suggested that certain

countries need to do better on their own human rights, their own

internal challenges, the response has been, 'Well, tell me about the

plight of Indigenous people [in Canada].'"

It is Canada's image which

concerned the Prime Minister when he spoke at the UN in the

General Debate on September 21. Posturing as a senior statesman even

though he has barely been in office for two years, Trudeau said: "In

conversations over the years, when I've suggested that certain

countries need to do better on their own human rights, their own

internal challenges, the response has been, 'Well, tell me about the

plight of Indigenous people [in Canada].'"

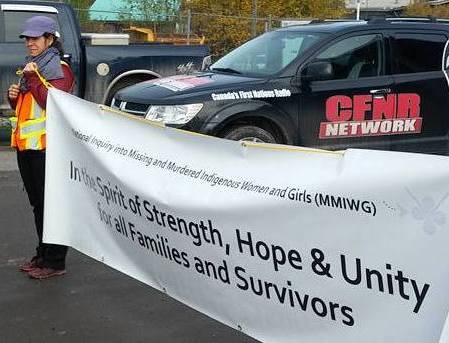

If Canadian governments

were to recognize the hereditary rights of the Indigenous peoples

in deeds, there would not be so many disputes and cases before the

courts or Indigenous youth in jail or missing and murdered women and

girls or suicides on reserve and in urban centres. The agencies

of government would not be permitted to

deprive the Indigenous peoples of their due which includes the

affirmation of their rights as human beings in matters of health

care, education, housing, justice and all other matters.

If Canadian governments

were to recognize the hereditary rights of the Indigenous peoples

in deeds, there would not be so many disputes and cases before the

courts or Indigenous youth in jail or missing and murdered women and

girls or suicides on reserve and in urban centres. The agencies

of government would not be permitted to

deprive the Indigenous peoples of their due which includes the

affirmation of their rights as human beings in matters of health

care, education, housing, justice and all other matters.

- Indigenous peoples be

permitted to conduct independent

environmental impact studies;

- Indigenous peoples be

permitted to conduct independent

environmental impact studies;

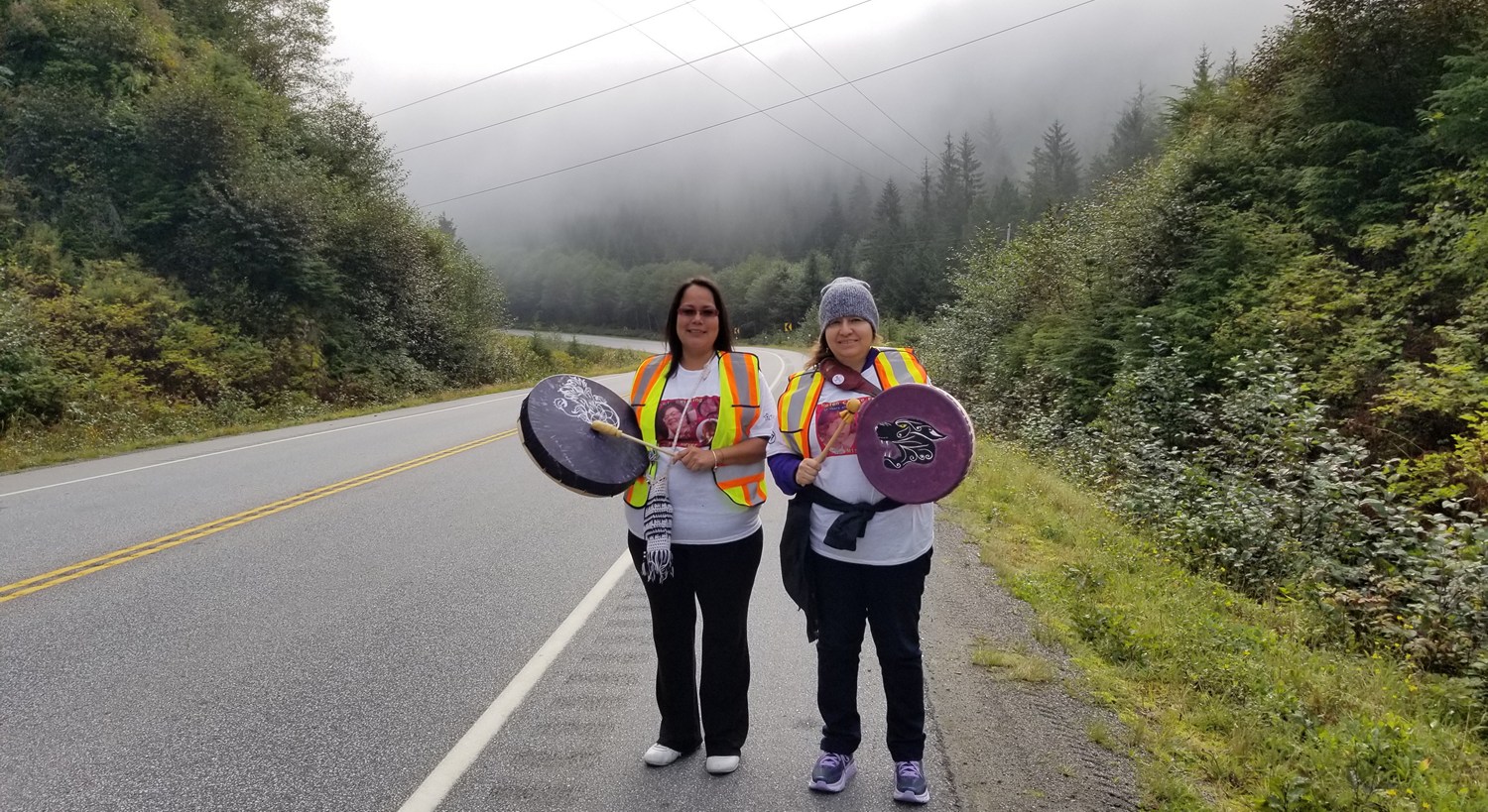

UBCIC President Grand Chief

Stuart Phillip and several other

chiefs and leaders also addressed the rally. Sto:lo activist and

Wild Salmon Defenders' Alliance spokesperson Eddie Gardener

warned that wild salmon are being devastated by and face

extinction as a result of Department of Fisheries' policies and

the provincially-licensed fish farms. Gardener vowed that

activists will escalate their opposition and do "whatever it

takes" to protect the salmon.

UBCIC President Grand Chief

Stuart Phillip and several other

chiefs and leaders also addressed the rally. Sto:lo activist and

Wild Salmon Defenders' Alliance spokesperson Eddie Gardener

warned that wild salmon are being devastated by and face

extinction as a result of Department of Fisheries' policies and

the provincially-licensed fish farms. Gardener vowed that