|

November 26, 2016 - No. 46

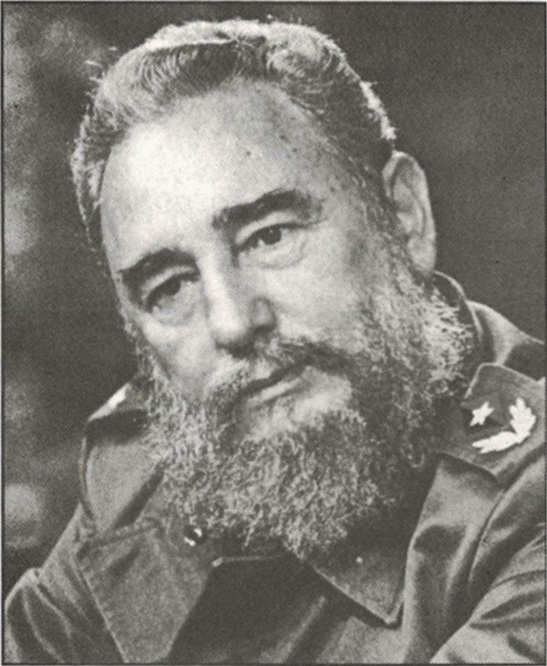

In Memoriam

¡Hasta la

Victoria Siempre,

Fidel!

|

August 13, 1926 –

November 25,

2016

|

|

• Message

from Cuban President Raúl

Castro

• Decree on National Period of Mourning

- Council of State of the Republic of Cuba -

• Press Release Regarding

Nationwide

Tributes to Fidel

- Funeral Organizing Commission -

Events

• Vigils to Honour the Revolutionary

Life and Work of Fidel

Remembering the Life and

Work of Fidel Castro

• Statement of the Canadian Network

on Cuba

• Principles Are Worth More Than

Life Itself

- Fidel Castro, 1994 -

• One Hundred Images of the Cuban

Revolution -- 1953-1996

- Introduction by Abel Prieto -

In

Memoriam

¡Hasta la Victoria Siempre, Fidel!

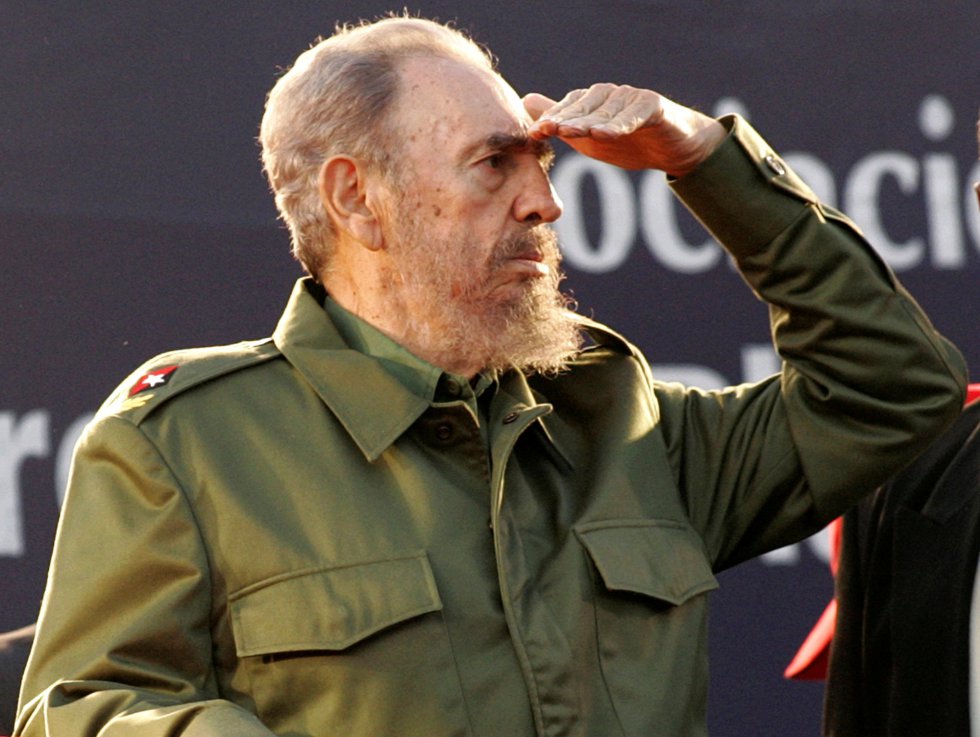

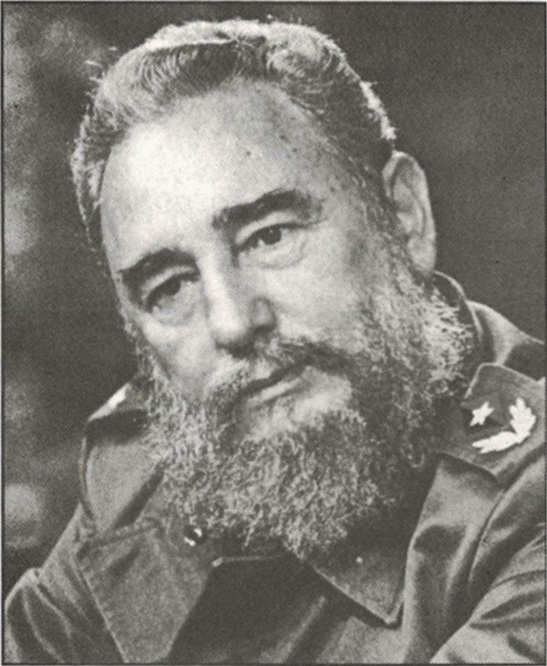

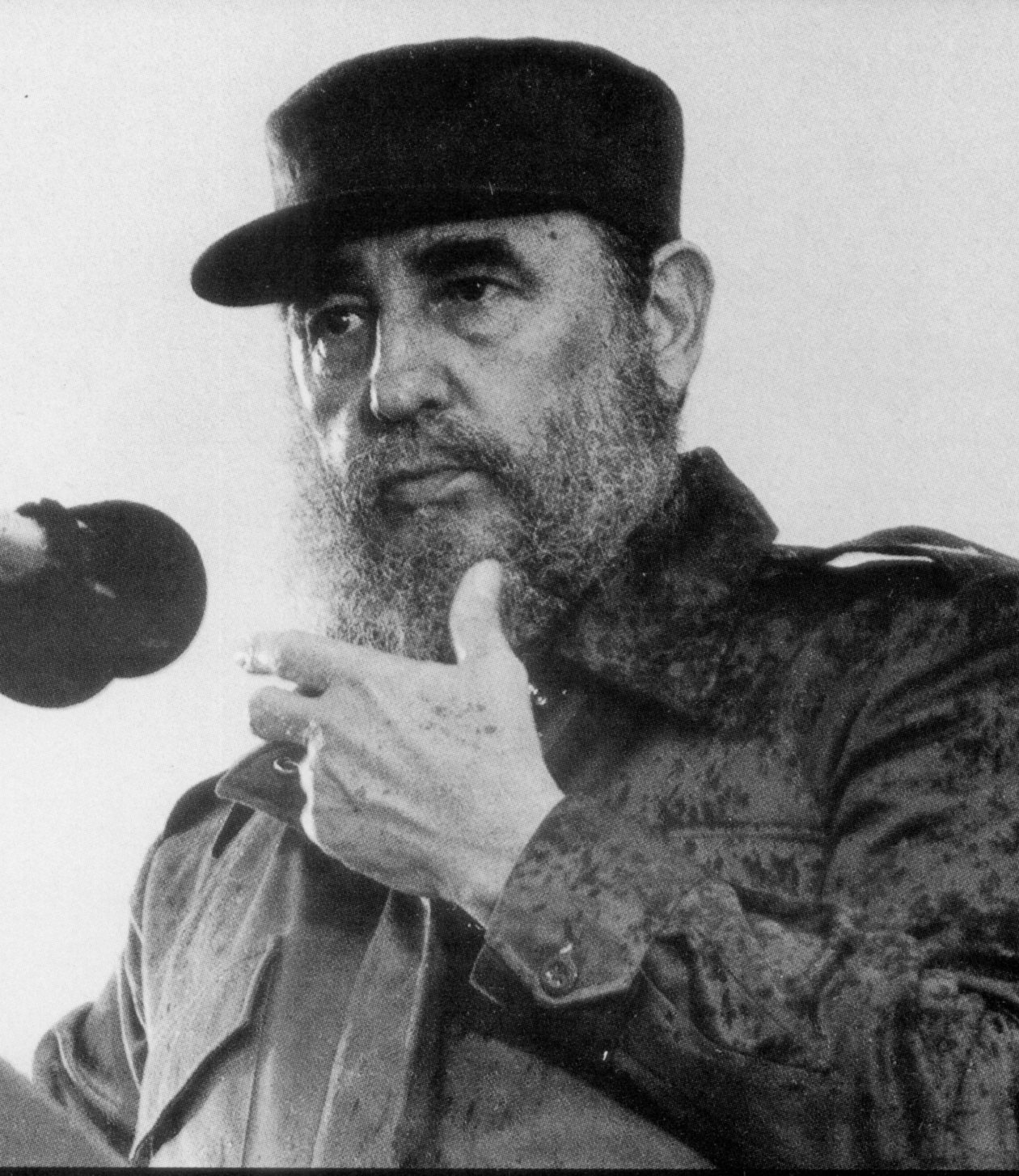

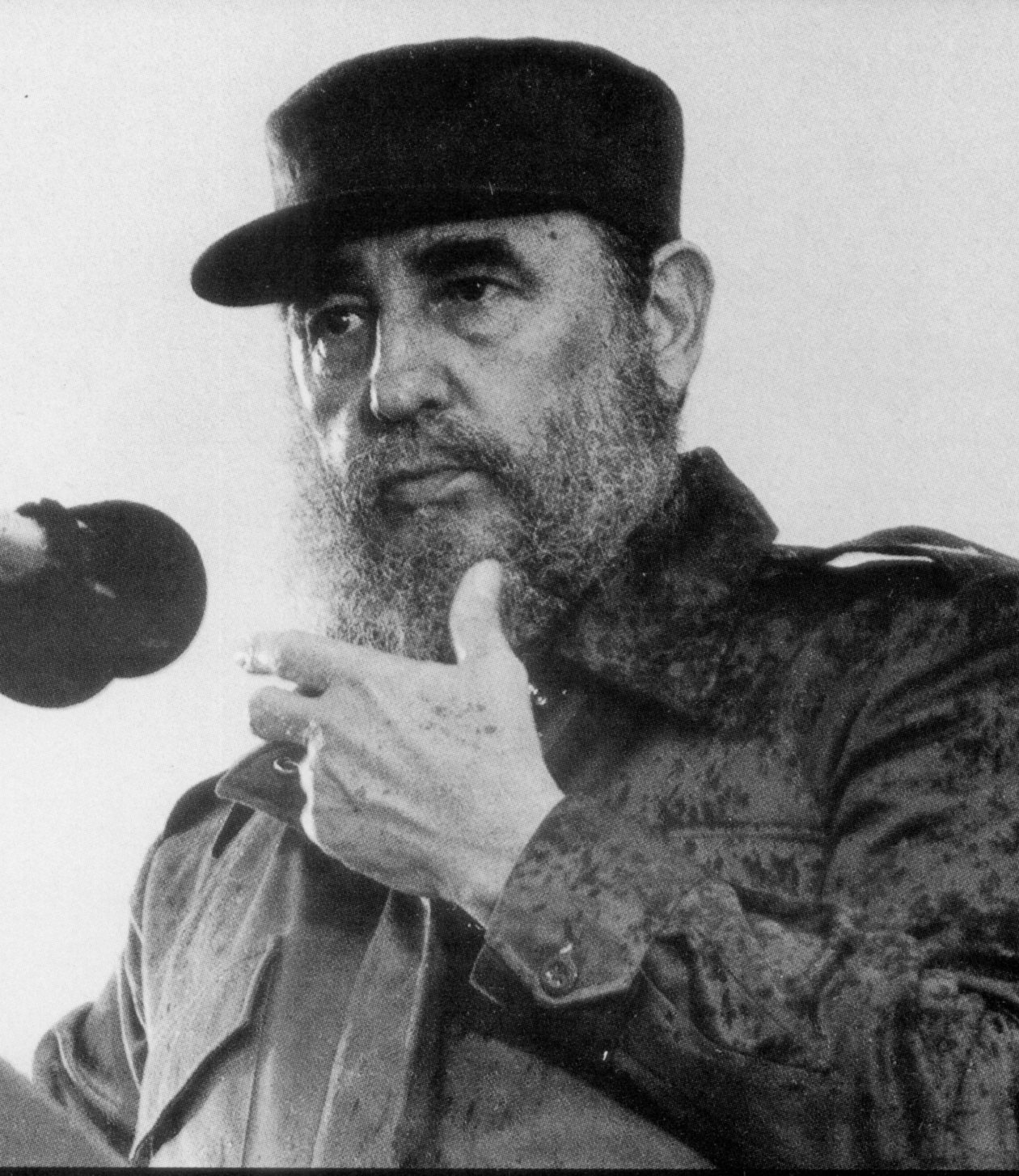

With deepest sorrow, the

Communist Party of Canada

(Marxist-Leninist) learned that on Friday, November 25, at 10:29

pm, Comrade Fidel Castro Ruz, leader of the ever victorious Cuban

Revolution, passed away.

We send our profound condolences on this very sad

occasion to

Comrade Raúl Castro and the entire Cuban leadership, to all the

Cuban people and their Communist Party and to Comrade Fidel's

family.

Comrade Fidel will live in our hearts in death as he

did in

life, inspiring us to defy all impediments to human and social

progress and to break new ground and reach new heights in all our

endeavours. May the revolutionary spirit, fidelity to principle

and the profound generosity which characterized Fidel's every

action imbue our thoughts on this very sad day.

¡Hasta la

Victoria Siempre!

Message from Cuban President Raúl Castro

Message from the President of Cuba's Councils of State

and

Ministers, Army General Raúl Castro, notifying the Cuban people

and world of the death of the late leader of the Cuban

Revolution, Fidel Castro.

***

Dear people of Cuba: Dear people of Cuba:

It is with deep sorrow that I come before you to inform

our

people, and friends of Our America and the world, that today,

November 25, at 10.29 pm, Comandante

en Jefe of the Cuban

Revolution Fidel Castro Ruz passed away. In accordance with his

express wishes Compañero Fidel's remains will be cremated. In

the

early hours of the morning of Saturday [November] 26, the funeral

organizing

commission will provide our people with detailed information

regarding the posthumous tributes which will be paid to the

founder of the Cuban Revolution.

¡Hasta la

victoria siempre!

Decree on National Period of Mourning

- Council of State of the Republic of

Cuba -

On the occasion of the passing of Commander in Chief

Fidel

Castro Ruz, the Council of State of the Republic of Cuba declares

nine days of National Mourning, from 06:00 on 26 November to

12:00 on 4 December 2016.

During the Period of National Mourning, all public

activities

and performances will be suspended; the national standard will

fly at half-mast at all public buildings and military

establishments. Cuban Radio and Television will be airing

informative, patriotic and historical programing.

Press Release Regarding

Nationwide Tributes to Fidel

- Funeral Organizing Commission -

The Organizing Commission of the Central Committee of

the

Party, State and Government for the funeral rites of Commander in

Chief Fidel Castro Ruz, informs the populace that as of 28

November, from 09:00 until 22:00, at the José Martí

Memorial,

the

population of the capital may present themselves to pay their

respects in tribute to their leader. The hours will be extended

until 29 November from 9:00 to 12:00.

On 28 and 29 November, from 09:00

to 22:00, at

locations to

be notified at the opportune time, in every city and town

including the capital Havana, every Cuban will have the

possibility of paying homage and signing the solemn oath to

fulfill the Concept of Revolution expressed by our historical

leader on the first of May of 2000, as expression of our will to

continue his ideas and those of our Socialism. On 28 and 29 November, from 09:00

to 22:00, at

locations to

be notified at the opportune time, in every city and town

including the capital Havana, every Cuban will have the

possibility of paying homage and signing the solemn oath to

fulfill the Concept of Revolution expressed by our historical

leader on the first of May of 2000, as expression of our will to

continue his ideas and those of our Socialism.

On 29 November, at 19:00, a mass rally will be held in

José

Martí Revolution Square of Havana.

The following day, his ashes will be taken along the

itinerary recalling The Caravan of Freedom of January 1959, to

the province of Santiago de Cuba, to conclude on 3 December.

On 3 December, at 19:00, a mass rally will be held at

Antonio

Maceo Square.

Burial will take place at 07:00 on 4 December at the

Santa

Ifigenia Cemetery.

We also inform our people that the Military Review and

the

March of the Combative People for the 60th anniversary of the

Landing of the Granma Expeditionaries, Revolutionary Armed Forces

Day, will be postponed until 2 January of 2017.

Events

Vigils to Honour the Revolutionary

Life and Work of Fidel

Across the country, vigils have been organized to

honour

Fidel and express the profound solidarity of Canadians with the

Cuban people and their revolution. Join in!

All events Sunday, November 27

Montreal

7:00

pm

Cuban

Consulate,

4546

Boulevard

Décarie

Ottawa

6:00

-

8:00

pm

Embassy

of

the

Republic

of Cuba, 388 Main St.

Toronto

5:00

- 6:30 pm

Cuban

Consulate, 5353 Dundas St. W.

Vancouver

4:00

- 6:00 pm

CBC

Plaza, 700 Hamilton St.

Remembering

the Life and Work of Fidel Castro

Statement of the Canadian Network on Cuba

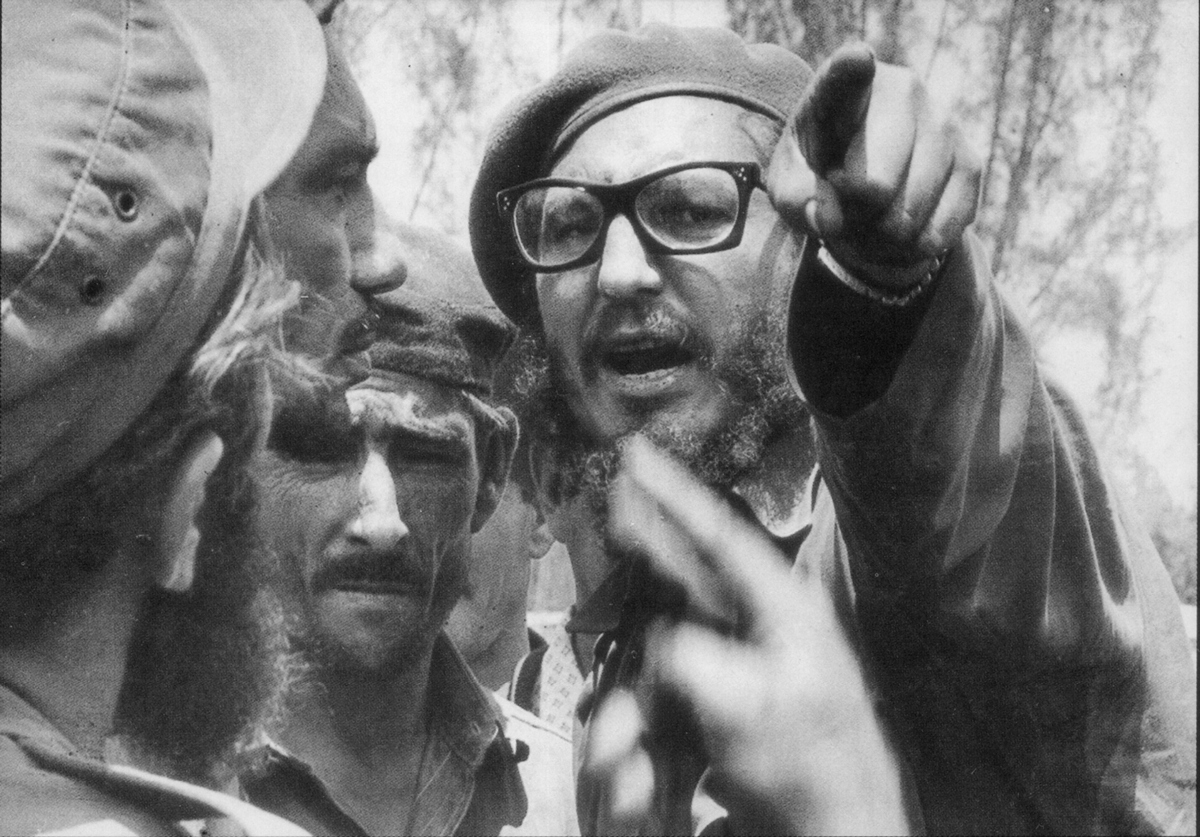

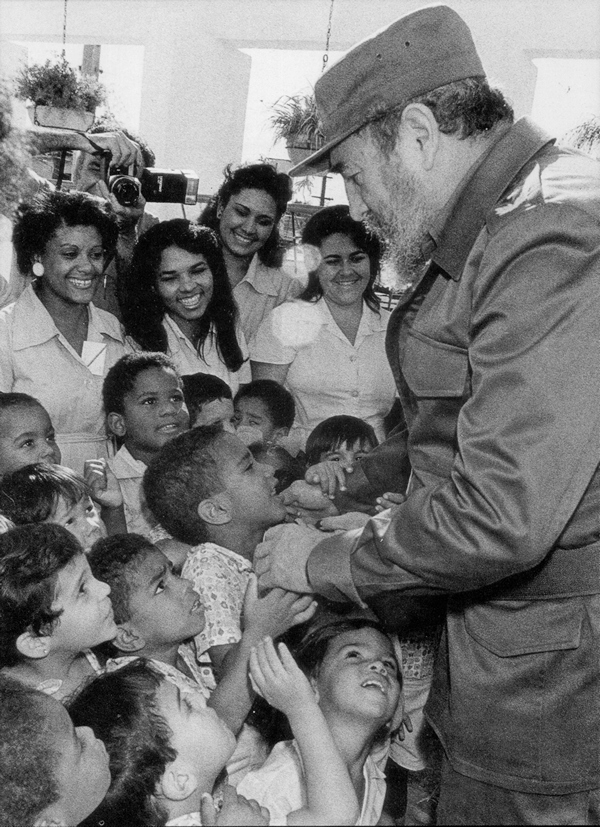

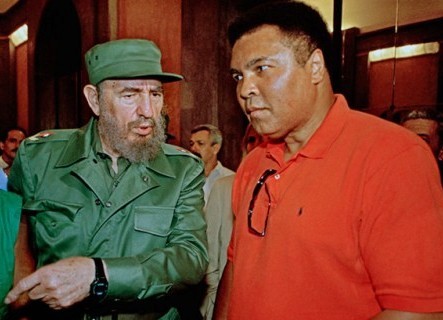

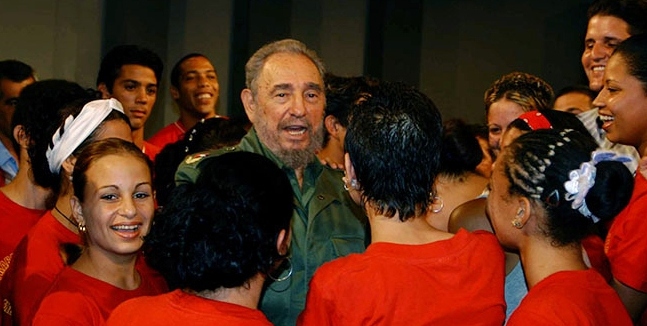

Fidel in discussion with Five Cuban Heroes shortly after their

return to Cuba, February 28, 2015.

It was with great sorrow and very heavy hearts that the

Canada-Cuba solidarity and friendship movement received the news

of the passing of Fidel Castro, the historic leader of the Cuban

Revolution. The profound sadness that we all feel in Canada is

shared by the progressive, anti-war and social justice forces

across the world.

Fidel is an integral member

of the pantheon of champions of

the people who made an indelible contribution to the global

struggle for liberation and emancipation. Fidel is an integral member

of the pantheon of champions of

the people who made an indelible contribution to the global

struggle for liberation and emancipation.

Fidel may be gone, but he lives on. Exemplifying the

finest

traditions of humanity, in the truest sense he belongs to the

world.

While the heart of Fidel may have ceased beating on the

night

of Friday, November 25, his legacy and work continue in the Cuban

Revolution, a living example that a better world is possible.

Fidel's life encapsulated the struggle of the exploited

and

oppressed. The legendary playwright Bertolt Brecht captured this

essence when he wrote: "There are men who struggle for a day and

they are good. There are men who struggle for a year and they are

better. There are men who struggle many years, and they are

better still. But there are those who struggle all their lives:

These are the indispensable ones."

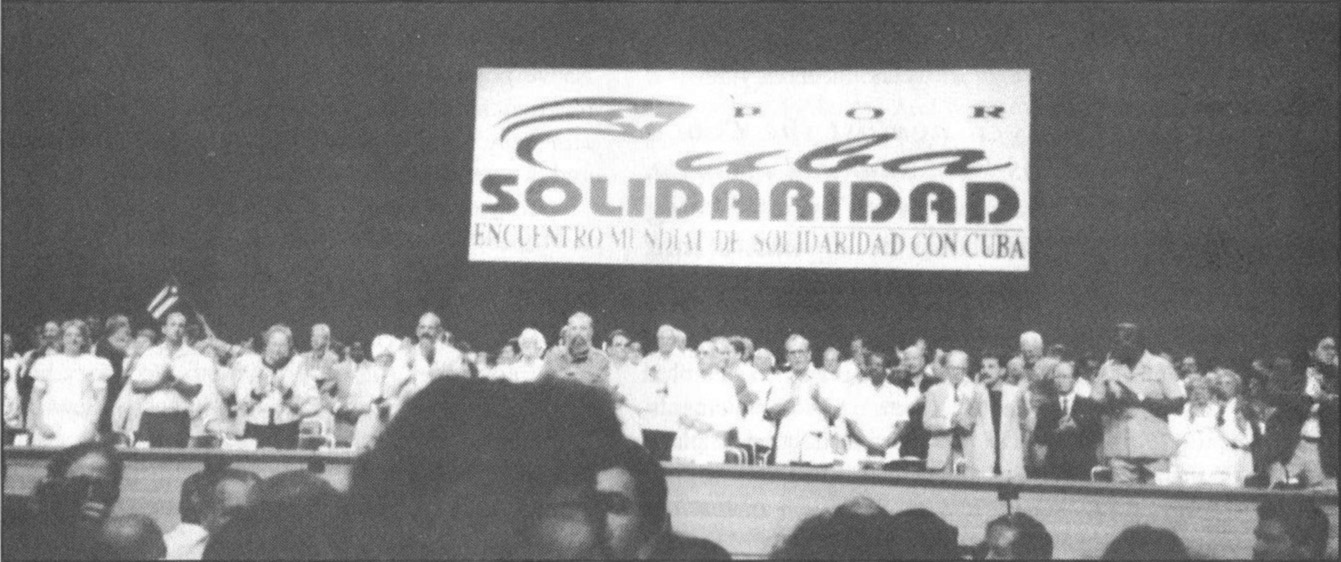

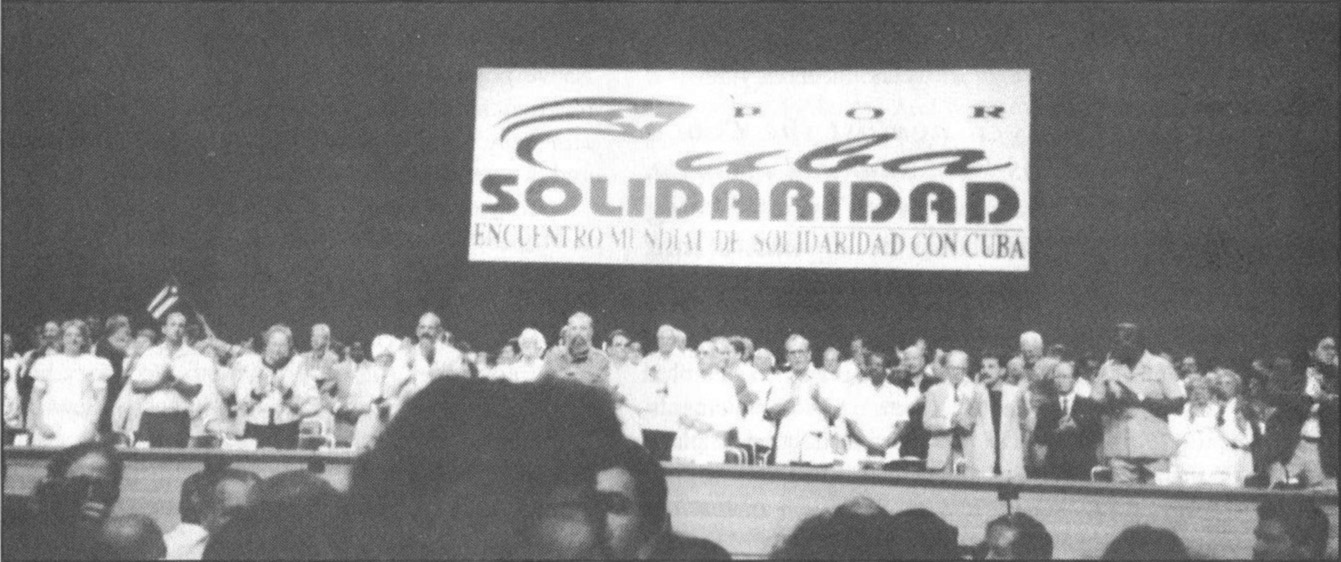

Principles Are Worth More Than Life Itself

- Fidel Castro, 1994 -

Speech given by

President

Fidel Castro Ruz, first

secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of

Cuba, at the closing session of the World Solidarity with Cuba

Conference, held in the Karl Marx Theatre, on November 25, 1994,

Year 36 of the Revolution.

***

Dear friends, and I say

"dear

friends" with great pleasure! It is difficult to summarize or

make a synthesis of the contents of these conference days, but I

can make some comments. Dear friends, and I say

"dear

friends" with great pleasure! It is difficult to summarize or

make a synthesis of the contents of these conference days, but I

can make some comments.

Throughout the last few days we have heard the best

sentiments and the best ideas of this century, expressed as a

call to battle, you could say. We have discussed many aspects

arising from humanity's concerns over many years. In one way or

another, you have expressed values for which humanity has battled

and fought throughout this century now drawing to a close.

Throughout this conference, you have discussed the

issues

central to the long-fought struggles for independence and against

colonialism, neocolonialism and imperialism -- the fight by the

world's peoples for equality, for justice, for their development,

for their sovereignty, never so threatened as today; the fight

for social justice, the fight against exploitation, the fight

against poverty, the fight against ignorance, the fight against

disease, the fight for all vulnerable and dispossessed peoples;

the fight for dignity, the fight for respect for women; the fight

for unity among all peoples and races; the fight for peace -- all

of these values and many more. Thus we could say that this has

not been just a conference of solidarity with Cuba, and it fills

us with pride that this solidarity has inspired such a

discussion.

The best values of our time have been reflected at this

meeting, and we have also seen the presence of many, though not

all -- for there are so many that they would never fit into 1,000

or 10,000 theatres such as this one -- of the world's finest, most

selfless and altruistic citizens, representatives of humanity's

best. This meeting has been attended by persons with the highest

human and moral sensibility.

I greatly admire humankind's capacity to give, to

sacrifice,

to show generosity, and each time we receive visitors to Cuba, I

observe them, assess them and try to gauge how they are thinking

and feeling. My admiration for so many human values never

ceases.

Absent from this meeting are many, many people whom we

know

as friends, who have demonstrated their solidarity and who have

been examples of sensitivity, solidarity and human generosity.

But those traits remain the indelible, unforgettable impression

that we will take away with us from this conference. How has

this conference unfolded and developed? Everyone I have talked

with has told me it has gone well; it has been unlike many of the

other conferences we have had, where everyone who wanted to speak

did so and the meetings became an interminable series of

speeches, and although this meeting has witnessed many excellent,

brilliant, profound and cogent speeches, an event many days

longer and dedicated to letting everyone speak would not have had

the same quality.

Thus there have been

speeches, statements from the floor,

questions and answers; we have had the working commissions on

various themes; those who did not speak here spoke there, and a

miracle has been worked to allow contributions from hundreds of

people, although it was impossible for everyone to speak.

I think that the people who did speak more or less

expressed

the sentiments of everyone present. For that reason, we have to

congratulate the organizers and leaders of this event, [applause]

since

in

spite

of

differences,

we

have

not

had

a

Tower

of

Babel

situation, and despite language diversity -- 109

countries are represented here, according to the information

given out -- we have understood each other perfectly well,

because, although we have different languages and even different

political opinions, we were unanimous in the noble idea of

solidarity with the Cuban people. [Applause]

The blockade has become the central issue of this

event. Many

people have talked on this subject; comrades have stated that

there is nothing much to add about the blockade. But,

essentially, what is the blockade? The blockade is not only the

prohibition by the United States for any kind of commerce with

our country -- whether it is technology or machinery; whether it

is something more, food; whether it is medicine. The blockade

means that they cannot sell to Cuba even an aspirin to relieve a

headache, or an anti-cancer drug which could save lives or

alleviate the suffering of the terminally ill; nothing,

absolutely nothing can be sold to Cuba!

The blockade is not only the prohibition of all credits

and

finance facilities. The blockade is not only the total closure of

economic, commercial and financial activities by the United

States, the world's richest nation, the most powerful nation of

the world in economic and military terms. It is not only just 90

miles off our coasts, but a few inches away from us, in the

occupied territory of the Guantanamo naval base. The most

powerful imperialist nation is not only close to us, but within

Cuba; and it is not only close to us with its ideas, its

theories, its concepts, its philosophy, but it is also among us

in that minority which unfortunately supports the concepts,

philosophy and ideas they have been disseminating for so many

years throughout the world.

The United States does not trade with markets

that

trade with

Cuba, but it does want to export ideas, and the worst ideas; it

does not export foodstuffs to Cuba, it does not export medicines,

technology or machinery to Cuba, but it does export incredible

quantities of ideas. What is happening now is that before the

ideas market was much wider, and it exported many ideas to the

socialist bloc, to the former Soviet Union and other countries;

these days the United States reserves its counter-revolutionary

ideas for us, from a vast and powerful stock of enormous,

infinite mass media programming. This trade is a one-way trade as

we do not have that kind of mass media, those enormous

communications systems which cost billions, ten of billions of

dollars every year, which we are condemned to receive, not to

exchange. The United States does not trade with markets

that

trade with

Cuba, but it does want to export ideas, and the worst ideas; it

does not export foodstuffs to Cuba, it does not export medicines,

technology or machinery to Cuba, but it does export incredible

quantities of ideas. What is happening now is that before the

ideas market was much wider, and it exported many ideas to the

socialist bloc, to the former Soviet Union and other countries;

these days the United States reserves its counter-revolutionary

ideas for us, from a vast and powerful stock of enormous,

infinite mass media programming. This trade is a one-way trade as

we do not have that kind of mass media, those enormous

communications systems which cost billions, ten of billions of

dollars every year, which we are condemned to receive, not to

exchange.

But the blockade is not only that; the blockade is an

economic war waged against Cuba, an economic war; it is the

tenacious, constant persecution of any Cuban economic deal made

anywhere in the world. The United States actively operates,

through its diplomatic channels, through its embassies, to put

pressure on any country that wishes to trade with Cuba, or any

business interest wishing to make commercial links with or invest

in Cuba, to pressure and punish any boat transporting cargo to

Cuba; it is a universal war, with an immense balance of power in

its favour, against the economy of our country, going to the

extreme of individual moves against persons or individuals who

attempt to undertake any economic activity in relation to our

country.

They euphemistically refer to it as an embargo; we call

it a

blockade, but it is not an embargo or a blockade; it is war! A

war solely and exclusively waged against Cuba and against no

other country in the world.

We have not only had to endure the blockade during the

years

of the Revolution; we have also had to endure incessant hostility

in the political sphere, from attempts to eliminate the

Revolution's leaders, through every known form of subversion and

destabilization, to direct and perennial sabotage of our

economy.

During the last 35 years, we have been the victims of

every

kind of sabotage. I am not just referring to piracy, mercenary

invasion, dirty wars in the mountains and the plains, consistent

and widespread destabilization attempts, but we have also been

the victims of direct sabotage involving explosives and

incendiary devices. Our country has also been subject to

chemical warfare, through the introduction of toxic elements, and

biological warfare via the introduction of plant, animal and

human diseases. There are no weapons or resources that have not

been used against our country and our Revolution by U.S.

authorities and governments.

But you don't have to take my word for it. From time to

time

documents appear, papers that have been declassified after 25

years, although there are others that are kept for 50 or 100

years; some say they hold them back for 200 years, something for

the grandchildren or the great-grandchildren or

great-great-grandchildren of the current generation, who will one

day learn about the barbarities which these "champions" of

freedom, these "champions" of human rights have committed.

The war waged against the Cuban Revolution has been

total and

absolute, and it is not an old war; it is still being maintained,

and plans are being made and carried out to sabotage our economy

and our strategic industries.

Currently, organizations closely linked to the U.S.

government are preparing to attack the Revolution's leaders --

nobody should think that this is a thing of the past, it's going

on right now. They are planning dirty wars, armed mercenary

infiltrations to kill, sabotage, create insecurity and to bring

death to every part of our country. I am saying this in all

seriousness, that such actions against Cuba are being planned by

the United States. This amounts to something more, much more than

an economic blockade.

All these policies come accompanied by an incessant

defamation and slander campaign against our country, as a

justification for their crimes. Now the fundamental emphasis is

being put on the human rights banner; human rights are being

quoted by those people who have committed and are committing all

kinds of atrocities against our country.

As I recently stated to the United Nations High

Commissioner

for Human Rights, with whom I conversed at length, the most

brutal and cruel violation of the human rights of our people is

being committed with the purpose of killing off 11 million Cubans

or bringing them to their knees through hunger and disease!

The United States talking about human rights! They

began by

exterminating their earliest Indigenous or Native population. Who

could forget that period and that tradition of collecting the

scalps of American Indians? They killed more American Indians

than buffalo, and they even finished off the buffalo. [Applause]

They expanded their country at the cost of other

territories;

they extended their country by grabbing land, thus dispossessing

their neighbours, in one way or another, of millions of square

kilometres of land. In terms of Mexico alone, they grabbed over

half of its territory; they still occupy Puerto Rico; they have

wanted to devour Cuba for over 150 years; they have intervened

dozens of times in Latin American countries; they imposed a canal

in Panama. This refers just to our hemisphere. I have not

mentioned the wars in Viet Nam, Laos, Cambodia and in many other

places.

What a history! And what a paradox that they have just

approved Proposition 187 -- this was not 100 years ago, nor 100

days ago, but just a few weeks ago -- to bar health care and

education for undocumented children, for those families living in

what was once Mexican territory. [Applause]

What respect for human rights are shown by these

concepts?

What ideas, what concepts about human beings? It's inconceivable

that a child could fall ill and not be treated, when $300 billion are

spent on the military budget and on the most

sophisticated weapons ever known!

We don't have to look back in history. In contemporary

times,

since the start of the Revolution, what has been the history of

the foreign policy of the United States, that "champion" of

freedom, that "champion" of human rights? A close alliance with

the most repressive and bloody regimes in the world.

If we turn to Europe, we can recall that immediately

after

World War I the United States became the ally of Spanish fascism,

which was supplied with weapons from Hitler and Mussolini and

which cost millions of lives.

We cannot overlook the U.S. alliance with South Viet

Nam and

its genocidal war against the Vietnamese people in the south and

north of that country. We cannot overlook the Korean war, because

Korea was completely demolished, reduced to dust. We cannot

ignore Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the unnecessary use of nuclear

weapons -- a completely unnecessary use which, in any event, could

have been used against military installations but instead fell on

civilian populations of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants. It

rang in the era of atomic terror in the world.

We cannot forget the alliance with South Africa and

apartheid. Neither can we forget that the apartheid regime built

its own nuclear weapons, and when we were fighting in southern

Angola against the apartheid army, alongside the Angolans, South

Africa already had nuclear weapons, various nuclear weapons! The

United States knew that South Africa had nuclear weapons and that

those nuclear weapons could have been used against Cuban and

Angolan soldiers. Ah! But this was the South Africa of racism and

fascism.

The United States has created a great fuss and has even

threatened war against North Korea, due to its assumption that

the North Koreans were developing nuclear weaponry, but it

tolerated, allowed and indirectly facilitated South Africa's

building of nuclear weapons.

But if we come closer to our continent, and to recent

times,

who could forget the dirty war in Nicaragua, orchestrated via

armed mercenaries, which cost tens of thousands of lives and the

mutilation of thousands and thousands of Nicaraguans? Who could

forget that? [Applause] The "champion" of freedom! The

"champion" of human rights!

Who could forget the dirty war in El Salvador, the U.S.

government support for a genocidal government to which it gave

billions of dollars in sophisticated weapons to trample on the

people's rebellion, a war that caused over 50,000 deaths?

And why did the Malvinas War happen? Simply because the

United States had been using Argentina's 401st special forces

battalion for its dirty war against Nicaragua and El Salvador,

and it provided such exceptional service to the United States

that the battalion felt it could occupy the Malvinas Islands.

This has nothing to do with Argentina's right to the

Malvinas, which we have always defended. [Applause] But

the Argentine military felt that the moment had come to collect

from the United States for services rendered in Central America,

so that the former would back them in their military adventure.

It was an adventure, in fact, because in the final analysis that

is not the way to wage war. You either wage war or you don't. And

if you wage war you take it to its ultimate consequences, if it's

a just war. [Applause] And they invaded the Malvinas

Islands. But when the United States was put into the position of

choosing between its allies and its British forebears, they chose

and backed the British.

Who can forget what has happened in Guatemala since

Arbenz'

government in the '50s, [applause] when a popular

government chosen by the people was trying to carry out agrarian

reform to help campesinos and Indigenous communities? Immediately

the dirty war broke out and they were invaded by mercenaries. And

what has happened since then? What has happened up until now?

Over 100,000 people have disappeared. This is a country where for

decades there were no political prisoners because everyone

disappeared. To this day, who supplies this government, who

trains it, who prepares it? The "champion" of freedom, the

"champion" of human rights. What happened in Chile with Salvador

Allende's government, which had great popular support? [Applause]

They

plotted

against

him,

the

economy

was

blocked

in

many

ways

and

conditions

were

gradually

created

for

a

coup

which

gave

the

country

thousands

and

thousands

of

disappeared persons and murders.

And what happened in Argentina with that military

government

I mentioned? They say at least 15,000 disappeared [the

audience tells him "30,000!"]. I say "at least," because I

don't want people to think I'm exaggerating and yet many say

there were 30,000; and some people here are saying even more. But

let's take my figures as the minimum. Are 15,000 disappeared

really a small amount?

And who provided weapons to this government, who backed

it,

who gave it political support, who made use of their services in

Central America? The "champions" of freedom, the "champions" of

human rights!

And what happened in Uruguay? And what happened in

Brazil?

And who supported the coup leaders and those who tortured and

killed people and made them "disappear"? Who invaded the

Dominican Republic at the time of the Caamano rebellion? [Applause]

Who

invaded

Grenada?

[Applause]

Who

invaded Panama? [Applause] The "champions" of freedom

and human rights!

Which of those governments was harassed? Which of the

governments I named have been blockaded? Which of them have been

denied credit and trade? Which was denied the purchase of weapons

and war materiel? Who didn't they train in so-called

antisubversive action? Who didn't they train in the arts of

crime, disappearances and torture? And these are the ones who

blockade Cuba, who slander Cuba, who accuse Cuba of human rights

violations to justify their crimes against our people.

And I can say dispassionately, without being

subjective, that

Cuba is the country that has done the most for human beings. [Prolonged

applause

and

shouts]

What revolution was more noble? What revolution was

more

generous? What revolution showed most respect for people? And I'm

not only talking about a victorious revolution in power, but

since the time of our own war, of our own revolutionary struggle,

which established inviolable principles, because what made us

revolutionaries was rejection of injustice, the rejection of

crime and the rejection of torture. During the 25 months that our

intense war lasted, in which we captured thousands of prisoners,

there was not one case of physical violence to obtain

information, not even in the midst of the war [applause];

there was not one case of killing a prisoner. What we would do

with prisoners is set them free -- we would keep their weapons,

which was all we were interested in, and we treated these arms

suppliers with all the consideration they deserved [laughter

and applause]. At first they had been led to believe that we

would kill them all, and in fact they would resist up to the

bitter end. But when they discovered during the course of the war

the true behaviour of the Rebel Army, they would give up their

weapons with less of a struggle when they were surrounded, when

they knew they had lost. Some of those soldiers surrendered three

times, because they were switched from one front to the other and

they were used to surrendering, they had experience. [Laughter and

applause]

But the most important thing is that the Cuban

Revolution has

maintained the principles of never resorting to torture, of never

stooping to crime, without exception to this day [applause],

no matter what they say, no matter what

they

write. We know that a lot of this slander has been written by

people in the CIA's pay.

Are there many other examples like it in history? In

the

world's history there have been many revolutions and in general

they were rough, very rough: England's civil wars, the French

Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War and the

Mexican Revolution. We know quite a bit about revolutions and

many books have been written about them and about

counterrevolutions. Well, one does not even speak of

counterrevolutions. Revolutions tend to be generous and

counterrevolutions are unfailingly merciless. Just ask the

members of the Paris Commune. [Applause]

In the case of Cuba there has not been one exception.

In the

whole history of the Revolution, there has not been one single

case of torture -- and I mean that literally -- not one political

murder, not one disappearance. In our country we do not have the

so-called death squads that sprout like mushrooms in this

hemisphere's countries. [Audience names several countries] You

speak for us! [Applause] We prefer not to mention

names, but everything has happened in our hemisphere.

Why is there no mention made of the United States,

where

people have been brutally murdered for defending civil rights,

men like Martín Luther King and many others, a country where as

a

rule only blacks and Hispanics are given the death sentence?

Our country does not have the phenomena we see in

others,

such as children murdered on the streets allegedly to avoid the

spectacle of begging and apparently to fight crime. The

Revolution eradicated begging, the Revolution eliminated

gambling, the Revolution eliminated drugs, the Revolution did

away with prostitution.

Yes, unfortunately there can be some cases or

tendencies that

due to the economic difficulties, and the opening to numerous

outside contacts encourages some "jineteras". We do not deny

this, and from time to time some may turn up on 5th Avenue, but

one should not confuse decent people with jineteras. [Applause]

Such

cases

exist

but

we

fight

against

it.

We

do

not

tolerate

prostitution;

we

do

not

legalize

prostitution.

[Applause]

There may be some children, encouraged by their

parents, who

approach tourists and ask them for gum or something else; these

are phenomena that we experience due to the special situation

that we are living in, at a time of great economic difficulties

as the blockade has been strengthened. But these things were not

known during the normal times of the Revolution.

You won't see people sleeping in doorways, covered with

newspapers, regardless of our present poverty. There is not a

single human being abandoned or without social security,

regardless of our present great poverty. [Applause] The

vices we see every day in capitalist societies do not exist in

our country. This is an achievement of the Revolution.

There is not one child without a school or a teacher,

there

is not one single citizen who does not receive medical care,

starting before birth. Here we start medical care for our

citizens when they are still in their mothers' wombs, right from

the first weeks after conception. [Applause]

We are the country in the world with the most doctors

per

capita, regardless of the special period, [applause] and

I'm not only referring to the Third World, but to the whole

world! More than the Scandinavians, more than the Canadians and

all those who are at the top rankings in public health. By

reducing infant mortality from sixty to ten per 1,000 live births

and with other paediatric programs, the Revolution has saved the

lives of more than 300,000 children.

We have the most teachers per capita in the world, [applause]

regardless

of

the

hardships

we

suffer;

we

have

the

most

art

teachers

per

capita

in

the

world;

we

are

the

country

with

the

most

physical

education

and

sports teachers per capita. [Applause]

That is the country that is being blockaded, that is

the

country that they are trying to bring to its knees through hunger

and disease.

Some demand that, in order for them to lift the

blockade, we

must surrender, we must renounce our political principles, we

must renounce socialism and our democratic forms. [Shouts of

"No!" "Never!"]

Furthermore, quite a confusing document was issued at

the Rio

Conference, despite the noble efforts against it by countries

like Brazil, Mexico and others. It was supported by some

countries that were very, very hand-in-glove with the United

States; I don't want to mention any names. It is a document with

a certain degree of confusion which leaves room for erroneous

interpretations, and some interpret it as supporting the U.S.

position of conditioning the blockade's suspension on Cuba making

political changes.

Political changes? Is there a country that has made

more

political changes than we have? What is a Revolution, if it's not

the most profound and extraordinary of political changes? [Applause]

We

made

this

Revolution

over

35

years

ago,

and

during

those

35

years

we

have

been

carrying

out

political

changes,

not

in

search

of

a

formal,

alienating

democracy which

divides peoples and splits them up, but rather a democracy that

really unites peoples and gives viability to what is most

important and essential, which is public participation in

fundamental issues. [Applause] Furthermore, we recently

made modifications to the Constitution, based on the principle

that the people nominate and the people elect. [Applause]

I'm not criticizing anybody, but nearly all over the

world,

including Africa, they are introducing Western political systems,

together with neoliberalism and neocolonialism and all those

other things, [to] people who have never heard of Voltaire, Danton,

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nor the philosophers of U.S. independence -- and

remember that Bolivar in our own hemisphere was very much

against the mechanical copying of the European and U.S. systems,

which have brought catastrophe, division, subordination and

neocolonialism to our countries. We can see societies splitting

into thousands of pieces, societies that should be united in

their efforts to develop have ended up not only with a multiparty

system but with hundreds and even thousands of parties.

We have worked, we've developed our own system, which

we did

not copy from anyone. We established the principle that those who

nominate in the first instance are the residents. One may or may

not agree, but it is as respectable as the Greek democracy that

people talk so much about and without slaves or serfs. Because

Greek democracy consisted of just a few that would meet in the

plaza, and they had to be few, because in those days they did not

have microphones, and they would get together to have an election

right there. [Laughter and applause] Neither the slaves

nor the serfs participated, nor do they today.

When you analyze the electoral results in the United

States

you discover that they have just elected a new Congress, where

undoubtedly there are worrying tendencies toward conservatism and

the extreme right, but those are internal matters in the United

States. The truth of the matter is, I can assure you, I promise

you, we have not made it a condition that the United States

renounce its system in order to normalize relations. [Laughter and

applause] Just imagine if we told them

that

they had to have at least 80 per cent of the electorate voting.

Thirty-eight per cent decided to vote and the rest said, "I'm

going to the beach," or "I'm going to the movies," [Laughter]

or "I'm going home to rest." This is what

happened to the "champions" of freedom, human rights and civil

rights. [Applause]

It is very much the same in many countries of Latin

America.

Many people don't even vote. The slaves and the servants say:

"What am I going to vote for, if I'm still going to be just the

same?"

How difficult it is for us to come to an agreement!

Because

it's certain that the influence of the mass media is greater all

the time and the series of obstacles that the popular forces have

to overcome are increasingly difficult.

However, 95 per cent of Cuban citizens vote in our

elections

and nobody forces them to vote. Even those who are not with the

Revolution go and vote, although they may turn in a blank ballot,

so as not to vote for this one or for the other; or they vote for

one or they vote for the other.

Right now, in our nation, I repeat once again, the

local

residents nominate the candidates, the people nominate the

candidates and the people elect them. In this way, the

possibilities of any citizen being elected are infinitely greater

than in any other country. One good example: I was talking with a

Mexican delegation and they said to me: "The youngest of our

deputies was here." "How old is he?" They told me: "Twenty-five

years old." I was really astounded, but then I suddenly

remembered that we have a number of deputies under the age of 20,

because the students, from secondary school onwards, take part in

the process of selecting candidates, as do all the mass

organizations. [Applause].

The campesinos take part in the process of selecting

candidates; the women's organization takes part in the process of

selecting candidates; the trade unions take part in the process

of selecting candidates; the Committees for the Defense of the

Revolution take part in the process of selecting candidates and

there are numerous students who are deputies to the National

Assembly and women, campesinos, workers and intellectuals, from

all sectors. It isn't the Party that puts up the candidates. The

Party does not put up the candidates nor does it elect them. It

oversees the elections to make sure that all of the principles

and the rules are observed; but it does not take part in any of

these electoral processes. That is the situation in our

country.

In one of the most recent modifications made in the

electoral

process, a candidate has to win more than 50 per cent of the valid

votes to become a deputy.

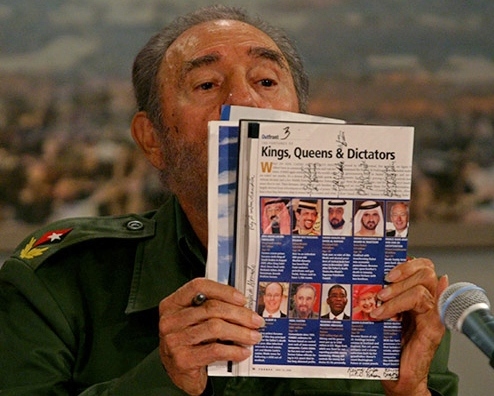

[Ricardo] Alarcón was explaining some of these

things, when he

recalled, with a magazine that he had in his hand -- he has the

advantage of speaking English and he reads a U.S. magazine now

and again [laughter] -- how one man had spent $25 million in a

campaign to become a member of the U.S. Congress.

What kind of democracy is that? How many people have $25 million to

spend on a campaign? And in Cuba candidates don't even

need to spend $25, although any citizen might have to pay

the bus fare to go and vote on the day of the elections. [Applause]

What kind of democracy is it that requires one to be a

millionaire to be able to have all the resources with which to

speak and persuade the people to vote for you, and then the

candidate doesn't remember those who voted for him until the next

elections four or five years later; he doesn't think about them

ever again; he forgets them.

In our country people can be removed from their posts,

and

the same applies to a municipal delegate as well as the highest

official. Anyone can be elected, but they can also be dismissed

from those posts. That is our system, which we don't expect all

the other countries to apply; it would be absurd to try to make

it a model; but it is the system that we have adopted; nobody

imposed it on us, no U.S. governor or supervisor came here to

establish an electoral code as they did before.

We drew up the Constitution ourselves, [applause]

we

drew

up

the

electoral

code

ourselves,

we

have

planned

the

system

ourselves

and

we

have

developed

it

ourselves,

which

is

what

you

have

been

defending:

the

right of a country to establish the

regulations, the economic, political and social system that it

considers to be appropriate. Anything else in the world is

impossible, anything else is absurd, any other aim is insane and

these lunatics go around trying to get everyone to do exactly the

same as them, and we don't like their way of doing things. [Applause]

That is why for us the question of ending the blockade

in

exchange for political concessions, concessions that correspond

to the sovereignty of our country, is unacceptable. It is

absolutely unacceptable, it is outrageous, it is exasperating and

really, we would rather perish than give up our sovereignty. [Prolonged

applause]

We have had the blockade for many years; however, it is

necessary to think about one fact: there was one world when the

Revolution triumphed; today, 35 years later, there is another

world. The world changed and didn't progress, it retrogressed,

because the bipolar world wasn't to anyone's liking, but the

unipolar world is much less to our liking.

When the Revolution triumphed, there was a bipolar

world. The

United States imposed the blockade on us from almost the first

moments. It began by doing away with the sugar markets, and it

cut off our supply of fuel. Imagine the new Revolution in those

circumstances! Of course they cut off our supply of machinery, of

spare parts, of everything, but there was the USSR and the

socialist bloc.

That was lucky for us, because faced with the U.S.

blockade,

90 miles away, there was another power in the world, another

movement in the world which had a revolutionary origin and which

was at odds with U.S. imperialism. Thanks to that movement we

could find markets for our sugar, supplies of oil, raw materials,

food, many things. That was explained here.

We were paid preferential prices; however, it is

necessary to

say that not only Cuba was paid preferential prices. The Lomé

Convention established preferential prices for sugar and other

products for many countries which were ex-colonies. In the United

States itself, when it was a major sugar market, there were also

preferential prices, before they snatched away our quota and

redistributed it throughout Latin America and other parts of the world.

Eighty per cent of the sugar in the world is traded through

preferential prices. And very much in accordance

with the principles of their political doctrine, the socialist

countries paid us preferential prices.

That was the policy which we defended for all of the

countries of the Third World, because it was the only way of

reducing the great difference that existed between the developed

countries and the underdeveloped countries. It was a demand of

the world, it was a demand of all the countries of the Third

World. And even so it was mutually advantageous, because although

they paid us preferential prices, it cost more to produce sugar

in the Soviet Union than the prices they paid us for sugar. But

at any rate, we benefited from those preferential prices, and we

used the money to purchase fuel, raw materials and many

things.

In our situation it so happened that the USSR and the

socialist bloc collapsed and the blockade got stronger. As long

as the socialist bloc and the USSR existed we managed better, we

could endure the difficulties. Our economy even grew under those

conditions throughout nearly 30 years and attained an

extraordinary social development.

However, it was in that world that the Cuban Revolution

was

born. There was no other, there were no other alternatives, in

the midst of the country being blockaded by the most powerful

country in the world. That is why the disappearance of the

socialist bloc and the USSR was such a terrible blow for us,

given that the existing blockade was not only maintained but was

also strengthened. For that reason our country lost 70 per cent of

our imports, and I wonder if any other country in the world would

have been able to withstand a similar blow, and I wonder how many

days they would have been able to withstand it -- a week, two

weeks or a month. [Applause] How would we have been able

to if it hadn't been for the people's support for the Revolution?

How would we be able to withstand it without our political

system, without our democratic system, without the people's

direct participation in all of the fundamental issues, which is

true democracy? [Applause]

Which other Latin American country could have been able

to

withstand the abrupt 70 per cent drop in imports? Would any

European country have been able to endure a similar trial? The

politicians would have abandoned their principles and capitulated

in an instant; but we have dignity, we have a sense of honour and

we stick to our principles. [Applause] For us these

principles are worth more than life itself and we have never sold

out our principles, never! [Applause]

When we helped the Central American revolutionaries,

the

United States said that they would remove the blockade if we

stopped helping them, and nothing of the kind ever crossed our

minds. [Applause] On other occasions they said that they

would be prepared to remove the blockade if we stopped helping

Angola and other African countries, and the idea of selling out

our relations with other countries never crossed our minds. On

other occasions, they said they would remove the blockade if we

broke off our links with the Soviet Union, and it never occurred

to us to do anything of the kind, because we are not a party or a

political leadership that sells out its principles. The blockade

will never end at that price, because it is a price that we are

not prepared to pay.

That situation led us to the special period.

We had been working on some excellent programs before

the

socialist catastrophe, excellent programs in all fields; we were

carrying out a process of rectification of errors and negative

tendencies, of old errors and new errors, of old tendencies and

new tendencies, and we were working very intensely when that

debacle led us into what we could call a double blockade, because

as soon as the breakup of the socialist bloc and the breakup of

the USSR occurred and even before the breakup of the USSR, the

United States was strongly pressuring those countries to stop

trading with Cuba, and when the USSR finally disintegrated, the

United States put on extreme pressure, and not without success,

to cut off trade and economic relations between the countries of

the old socialist bloc, the USSR and Cuba.

So our country found itself enveloped in a double

blockade

and, nevertheless, we had to save the nation, we had to save the

Revolution and we had to save socialism -- we talk about saving

the gains of socialism, because we can't say at this time that we

are building socialism, but rather that we are defending what we

have done, we are defending our achievements. This is a

fundamental objective in a world that has changed in such a

radical way, in which all the power of the United States has been

turned against us; because, for example, they don't impose

conditions on China, a huge country, an immense country, which

defends the ideas of socialism; they don't impose conditions on

Viet Nam, a marvellous and heroic country. Today there is no

blockade against them, but there is a blockade against us. Put

yourselves in the place of our Party and our government. And in

these such difficult conditions that have never existed before,

we must save the nation, save the Revolution and save the

achievements of socialism.

What measures would it be necessary to take in this

world

which exists today and which, of course, won't always exist?

Those are illusions held by those who believe that neoliberalism

is already the nec plus ultra, that it is the be-all and

end-all for capitalism; these are illusions that they have. [Applause]

The

world

will

teach

us

many

lessons.

What

is

going

to

happen

with

all

of

this

would

take

a

long

time

to

explain,

and

would

be

much

too long for us to bring up now, but

for them it's never-ending.

Now they talk about the globalization of the economy.

We'll

see what is left from this globalization for the countries of the

Third World, with the disappearance of all the current defense

mechanisms of the Third World, which must compete with the

technology and the immense development of the industrialized

capitalist countries. Now the industrialized countries will try

more than ever to exploit the natural resources and the cheap

work force of the Third World, to accumulate more and more

capital. However, it is superdeveloped capitalism, like in

Europe, for example, that has more unemployed people all the

time, and the more development, the more unemployed there are.

What will happen with our countries? There will be a

globalization of the differences, of the social injustice, the

globalization of poverty.

However, this is the world we've got, with which we

must

trade and exchange our products, in which we have to survive.

That is why we must adapt to that world and adopt those measures

which we consider essential, with a very clear objective.

This is not to say that everything that we are doing is

solely the result of the new situation. We have made changes as

we go along, and even the idea of introducing foreign capital

came up before the special period: we had realized that specific

areas, specific fields could not be developed because there

wasn't the capital or the technology to do so, because the

socialist countries didn't have them. However, we have had to

open up more, we have had to create what we could call a pretty

large opening to foreign investment. That was explained here: in

Cuba's circumstances today, without capital, without technology

and without markets, we couldn't develop. Hence, all of the

measures, changes and reforms that we have been making, in one

way or another have the objective, as was stated in this

conference, of safeguarding our independence and the Revolution,

because the Revolution is the source of everything, and the

achievements of socialism, which is to say to preserve socialism

or the right to continue constructing socialism when

circumstances allow it. [Prolonged applause]

We are making changes, but without giving up our

independence

and sovereignty; [applause] we are making changes, but

without giving up the real principle of a government of the

people, by the people and for the people, that, translated into

revolutionary language, is the government of the workers, by the

workers and for the workers. [Prolonged applause and shouts

of "Fidel, Fidel!"] It's not a government of the

bourgeoisie, by the bourgeoisie and for the bourgeoisie; nor a

government of the capitalists, by the capitalists and for the

capitalists; nor a government of the transnationals, by the

transnationals and for the transnationals; nor a government of

the imperialists, by the imperialists and for the imperialists. [Applause]

That is the big difference, whatever changes and

reforms we

carry out. If some day we renounced all this, we would be

renouncing the lifeblood of the Revolution.

We have shown solidarity with the world; it's not our

task

now to talk about this solidarity. As far as our solidarity is

concerned, we should do the most and talk the least, because

we're not going to make any apology for our conduct.

A few minutes ago, before starting the final part of

this

event, a comrade said: "Look at how many things Cuba has done!

When visitors from one country or another talk, when they talk

about doctors, students, people that were trained here, in one

activity or another, it is clear that in these years our country

has carried out many things. For us, solidarity and

internationalism are a matter of principle, and a sacred one at

that." [Applause]

To provide an example, I'm going to give a few

statistics.

More than 15,000 Cuban doctors have given free services in dozens

of countries in these years of the Revolution, more than 15,000

doctors have fulfilled internationalist missions as doctors; [applause]

more

than

26,000

teachers

and

professors.

I

ask

if

any

other

small

country,

and

even

medium

or

big

countries,

has

had

this

record.

Suffice it to say that at one point we had three times

more

doctors working for free in the Third World than did the World

Health Organization, [applause] and we didn't have a lot

of resources either, only minimum resources. We only had the

honour of our health workers, with their internationalist

calling. How many lives have they saved? And I wonder, is it fair

to blockade a country that has done this? [Shouts of

"No!"]

How many hundreds of thousands of children have we

educated

with our teachers in foreign countries? And we haven't only sent

primary and secondary school teachers, but university professors;

we have founded medical schools in diverse countries of the

world. Is it fair to blockade a country that has done all this,

and still does it to a certain degree? Half a million Cubans have

completed internationalist missions of different types, half a

million Cubans! [Applause]

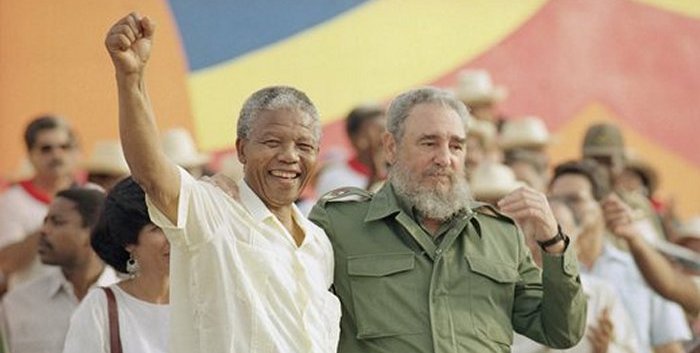

The Africans have been very generous, very noble, and

have

wanted to recall here Cuba's solidarity and aid in the war

against colonialism, the war against foreign aggression, the war

against apartheid and racism.

Like I said here, our soldiers were fighting in

southern

Angola, 40,000 men, 40,000 men! [Applause] They were

fighting alongside the Angolan troops, who acted and fought

heroically. There were Cubans in southern Angola facing up to the

South Africans after the battle of Cuito Cuanavale, and when our

counter-offensive was launched in southwest Angola, these men

were exposed to the possibility of nuclear warfare. We knew it,

and the distribution of forces in that offensive took into

account the possibility that the enemy could use nuclear

weapons.

At one point we had 25,000 foreign students in our

universities. [Applause] Cuba was the country with more

scholarships per capita than anywhere else in the world, and we

didn't brag about it; we just went on our way, fulfilling the

task of education as Martí taught us, and we did what we could

for other countries.

I think that this extraordinary conference, your noble,

generous words of solidarity reflect in part the history of our

own Revolution's solidarity. [Applause] This has greatly

encouraged us and gives us the strength to keep going.

There are a lot of choices in this day and age: the

choice of

freedom, the choice of sovereignty, the choice of independence,

and the choice of social justice.

Social justice is acquiring such force as an idea -- in

the

midst of neoliberalism, which is the negation of every principle

of justice -- that even some international agencies talk about it.

The Inter-American Development Bank talks more and more about the

need for social justice in this hemisphere. Even the World Bank

is talking about social justice! They're the champions of

neoliberalism and they talk about social justice, because they

realize that the differences are so great and are still growing,

and they would like to make the dream of neoliberalism come true,

of capitalism with social justice. They're afraid that misery,

hunger and poverty will undermine the bases of the neoliberalism

that they praise so much, and that is why they talk about social

justice.

But we know that only the people can achieve social

justice,

and that neoliberalism and social justice are incompatible,

they're irreconcilable; [applause] that a superdeveloped

world next to an underdeveloped world is incompatible,

irreconcilable. We know that the former will get richer and

richer, while the latter will get poorer and poorer, and this is

an irrefutable reality.

Your presence here shows that just ideas live on, that

noble

ideas live on, that values live on. And we have to multiply these

ideas and values just like Jesus Christ multiplied the loaves and

fishes. [Applause] The church talks about giving

opportunities to the poor, and this seems excellent to us, but I

think that today's world needs more than choices: it needs

energetic, tenacious and consistent struggle by the poor

themselves. [Applause and shouts of "Fidel, Fidel!"] I

should have said "churches"instead of "the church," considering

that we're not only talking about the Catholic church.

We must wage an unending battle against the causes of

poverty, [applause] an inexorable offensive against

capitalism, against neoliberalism, against imperialism, [applause]

until

the

day

when

we

can

no

longer

speak

of

billions

of

human

beings

who

are

hungry,

who

don't

have

schools,

hospitals,

a

roof

over

their

head,

or even the most elemental

means of living.

This planet is getting close to having six billion

inhabitants; in one century the population has increased

fourfold. The threats that humanity suffers today are multiple,

not only social, but economic, political and military.

Someone here was saying that nowadays they call wars

"humanitarian missions" or "peace operations." Wars threaten us from

all sides, interventions

threaten us from all sides; but the world is also being

threatened by destruction of the natural conditions for life, the

destruction of the environment, a problem which is getting more

and more attention and increasingly moves the conscience of

humanity. We will have to make a huge effort in every sense of

the word to save humanity from all these risks.

And what is the historical origin of this situation?

Could

anyone deny that it was colonialism, neocolonialism and

imperialism? Could anyone deny that it was capitalism? We are

very conscious of all this, despite the setbacks suffered by the

progressive movement, the revolutionary movement and the socialist

movement.

But we'll say it here and now, dear friends. We will

never

return to capitalism! [Applause] Not to savage

capitalism -- or as Perez Esquivel likes to call it, cannibal

capitalism -- or to moderate capitalism, if this exists; we don't

want to go back, and we won't go back! [Applause]

We know what our duties and obligations are. We've

withstood

almost five hard years already, when others thought the Cuban

Revolution would quickly disappear off the face of the earth. We're

working persistently and harder all the time, and even

putting more and more emphasis on the subjective, on our own

errors, our own deficiencies; emphasizing the subjective so that

the objective doesn't become a pretext for deficiencies.

We've still got to raise the consciousness of our

people. We

still have to explain why we need to reduce the excess currency

in circulation and the methods used to continue gathering up the

excess without using shock therapy; we have to look for

efficiency in agriculture and industry.

I know that the issue about food production has been a

worry

of yours, expressed here. I must say that we are obliged to

produce food without fertilizers, without pesticides, without

weedkillers, often without fuel, resorting to animal traction,

faced with the need to feed the 80 per cent of the population

living in urban zones. Cuba, unlike Viet Nam or China, has only

20 per cent of the population in the countryside and 80 per cent in

the cities. They have the inverse, 75 to 80 per cent in the

countryside and 20 to 25 per cent in the cities.

We even have a labour shortage in rural areas. Our

agriculture and sugar industry had been mechanized, like many

other sectors of the economy. Someone asked whether we should

produce sugar or not. We don't have any other choice than to

produce sugar, we have to produce it; now, it has become more

expensive for the sugar mills and machines to produce less

because of a lack of fertilizer and irrigation, for example. In

general, we know how to produce food, but we've had to deal with

a great scarcity of supplies for food production.

We've had to develop other areas. Tourism has already

been

mentioned here. It has become a necessity, although it wasn't

promoted in the first years of the Revolution, because it has its

good side and its bad side. And since we can't live with the hope

of being in an ivory tower, we have to get mixed up with the

problems of this world. And, based on the idea that virtue is

born of the struggle against vice, just as magnificent flowers

bloom from cow dung, [applause] we have to get used to

living with all these types of problems. We have to look for

resources in convertible currency to make these supplies

available.

The livestock has been left without feed, without

irrigated

land, without fuel.

The problems we've had to deal with aren't easy, but

we're handling it, sharing the little we have among many, rather than a

lot among a few. [Applause]

We've

been

sharing

what

we

have.

And

then,

under

these

incredibly

difficult

conditions

--

I

repeat,

there

is

not

a

single

school without a teacher, not a child without a

school, not a patient without a doctor or hospital; we maintain

social security, we maintain our cultural development, the

development of sports; we even came in fifth place in the Olympic

Games in the midst of the special period. [Applause]

This gives you an idea of our strength in exceptionally difficult

conditions.

Therefore, when we share the little we have among

everyone, a

lot of things can be done, and there are many countries in the

world that have much more than we do and do very few things. [Applause]

This event concludes, really, like an unforgettable

lesson

for all of us, and we hope for a lot, we hope for so much from

this battle that you propose to fight shoulder to shoulder with

us to end the blockade, to end the hostility against our country,

to defend hope. Not because we have been predestined to be

anyone's hope. We don't consider ourselves a people bound by

destiny; we constitute a small people, a modest people, to whom

history has in these particular circumstances assigned the role

of what we're defending: our most sacred ideals, our most sacred

rights. You all see this as hope.

We understand what it would mean for all the

progressive

forces, for all the revolutionary forces, for all lovers of peace

and justice in the world if the United States succeeded in

crushing the Cuban Revolution, and because of this we consider

defending the Revolution along with you to be our most sacred

duty, even at the cost of death.

Thank you, thank you very much, a million thank yous. [Applause]

And let me exclaim one more time:

Socialism or Death!

Patria o Muerte! Venceremos!

Long Live Solidarity!

[Shouts of "Long Live Solidarity!"]

[Ovation]

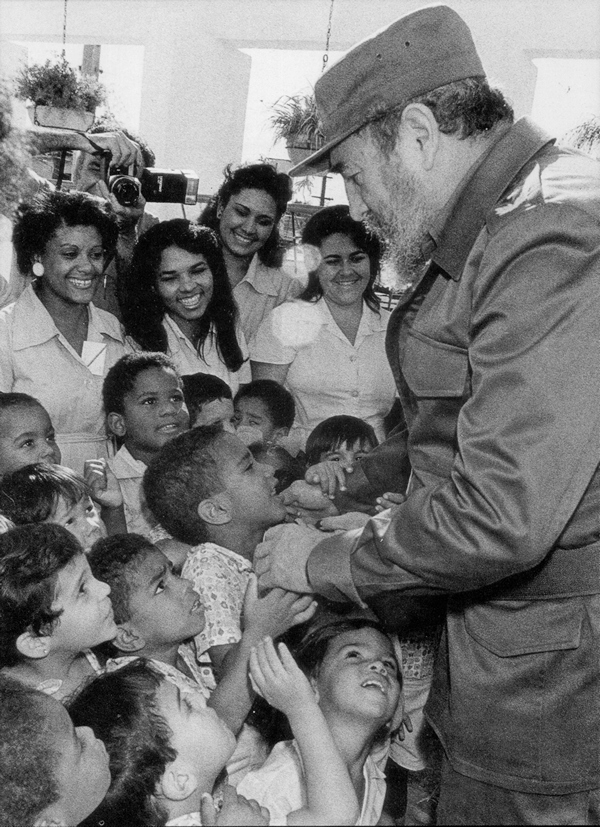

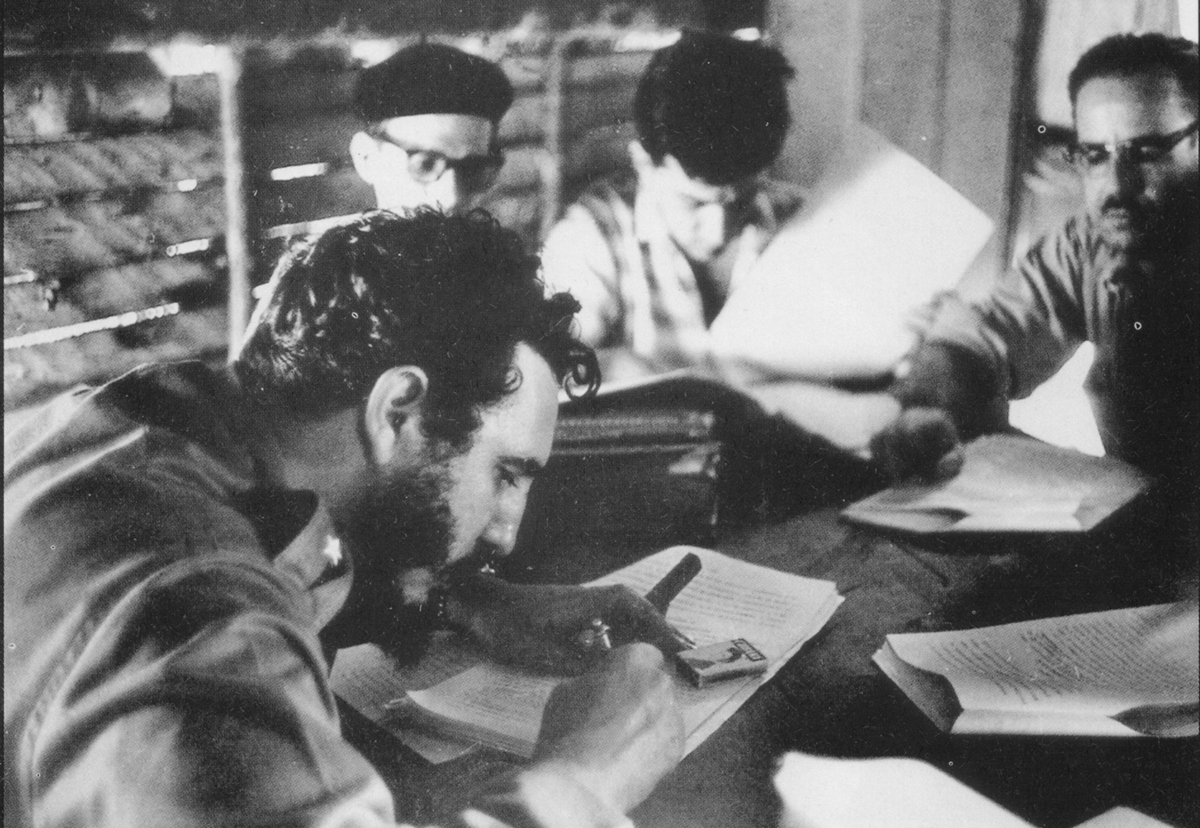

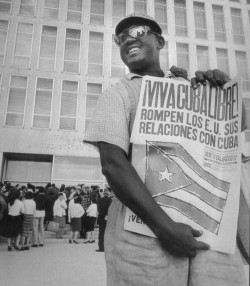

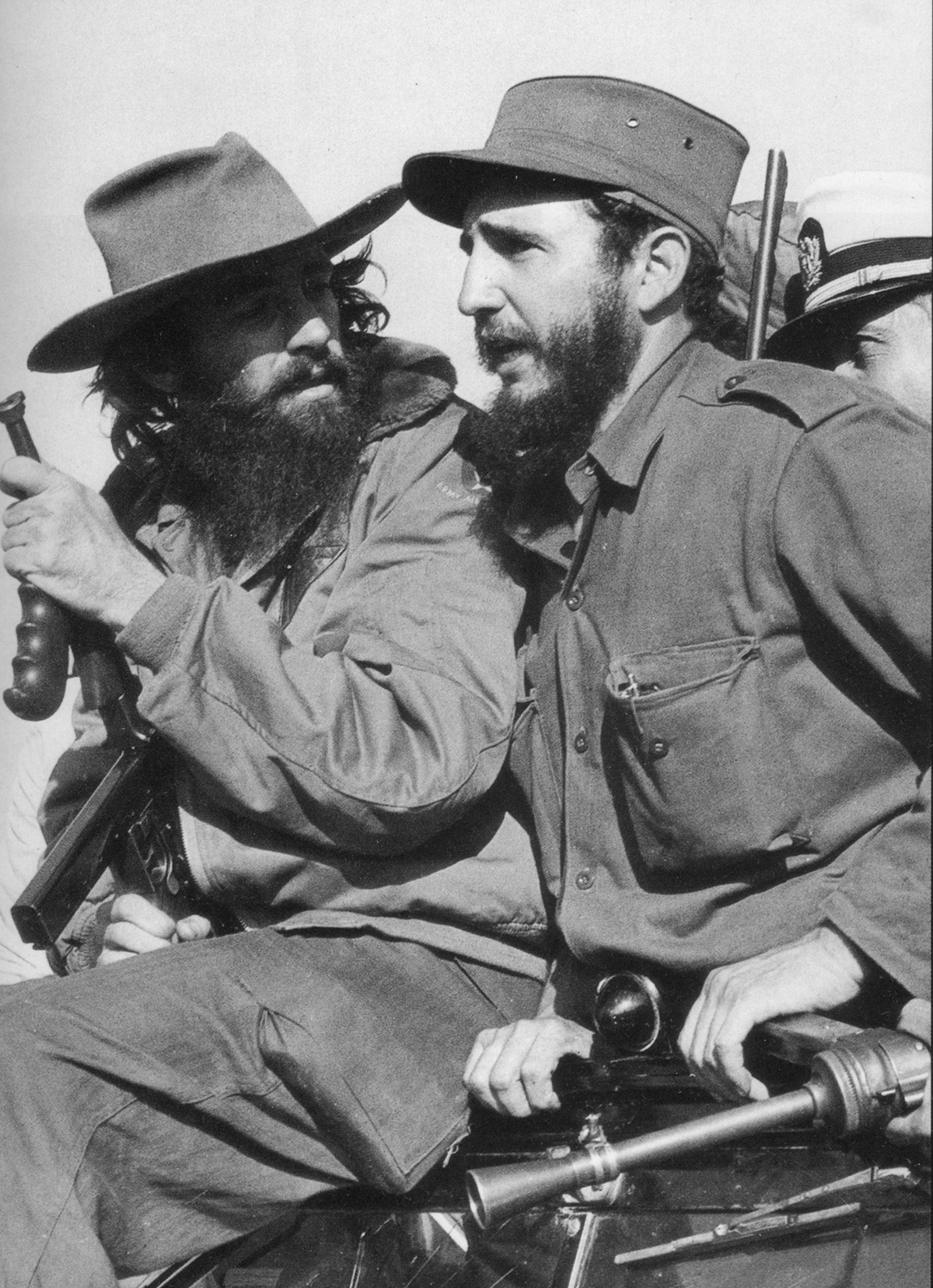

One Hundred Images of the Cuban Revolution -- 1953-1996

- Introduction by Abel Prieto -

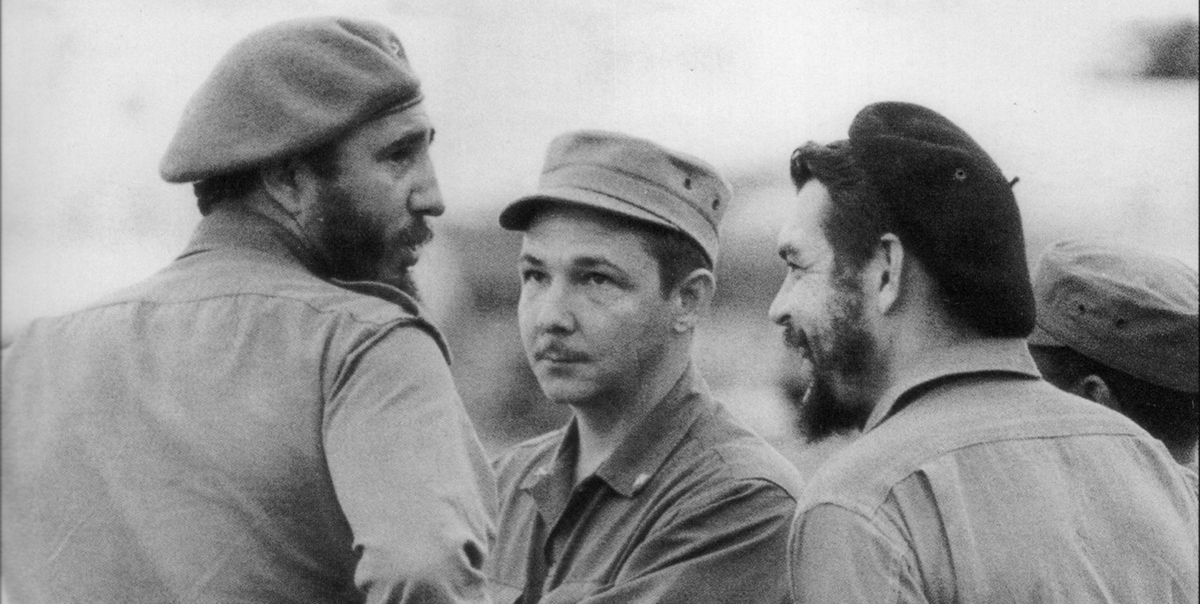

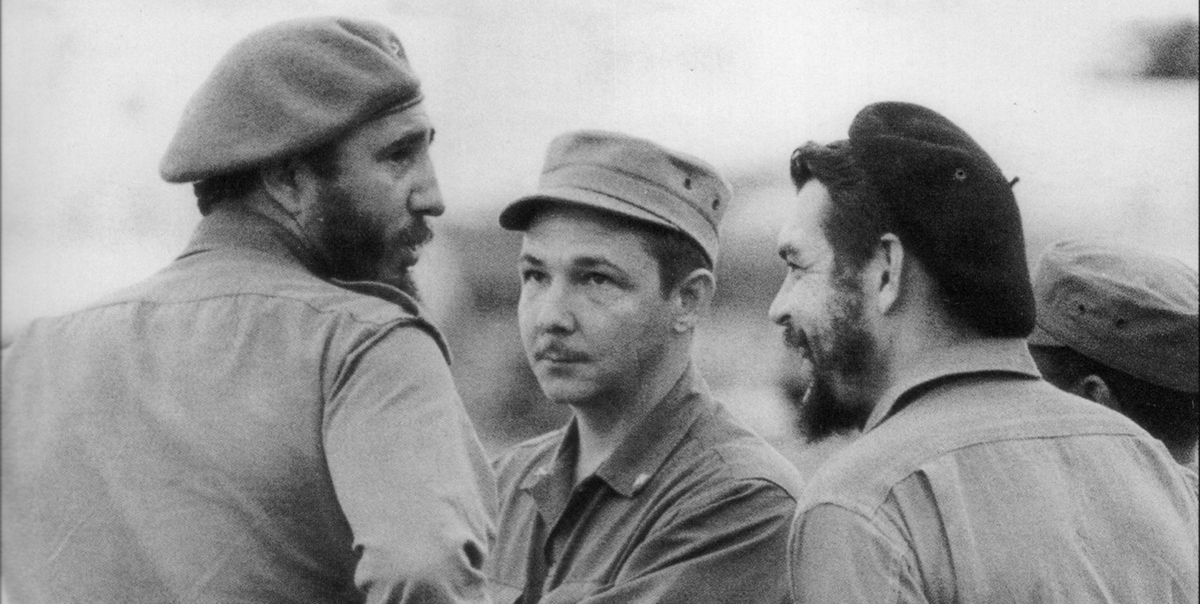

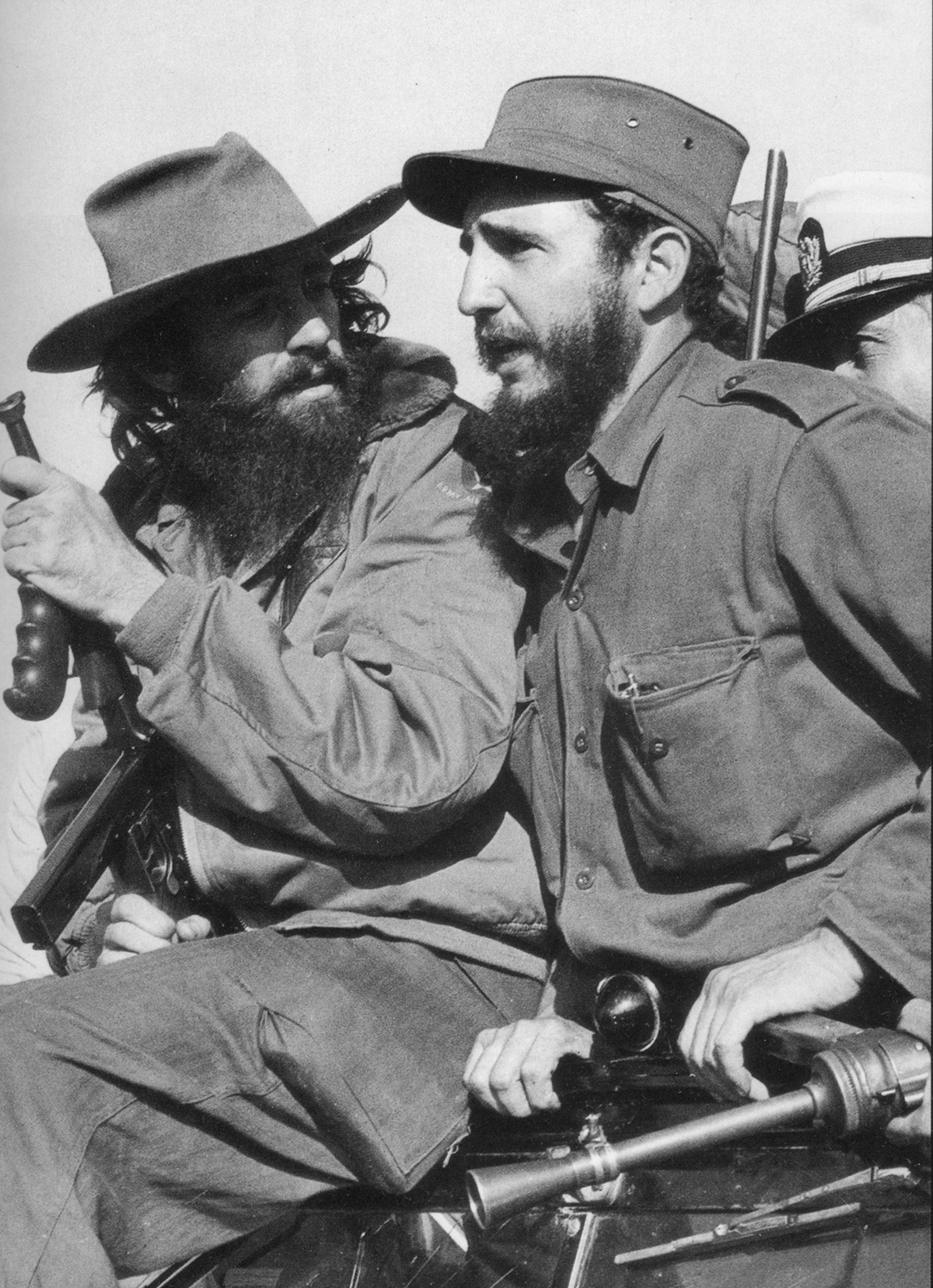

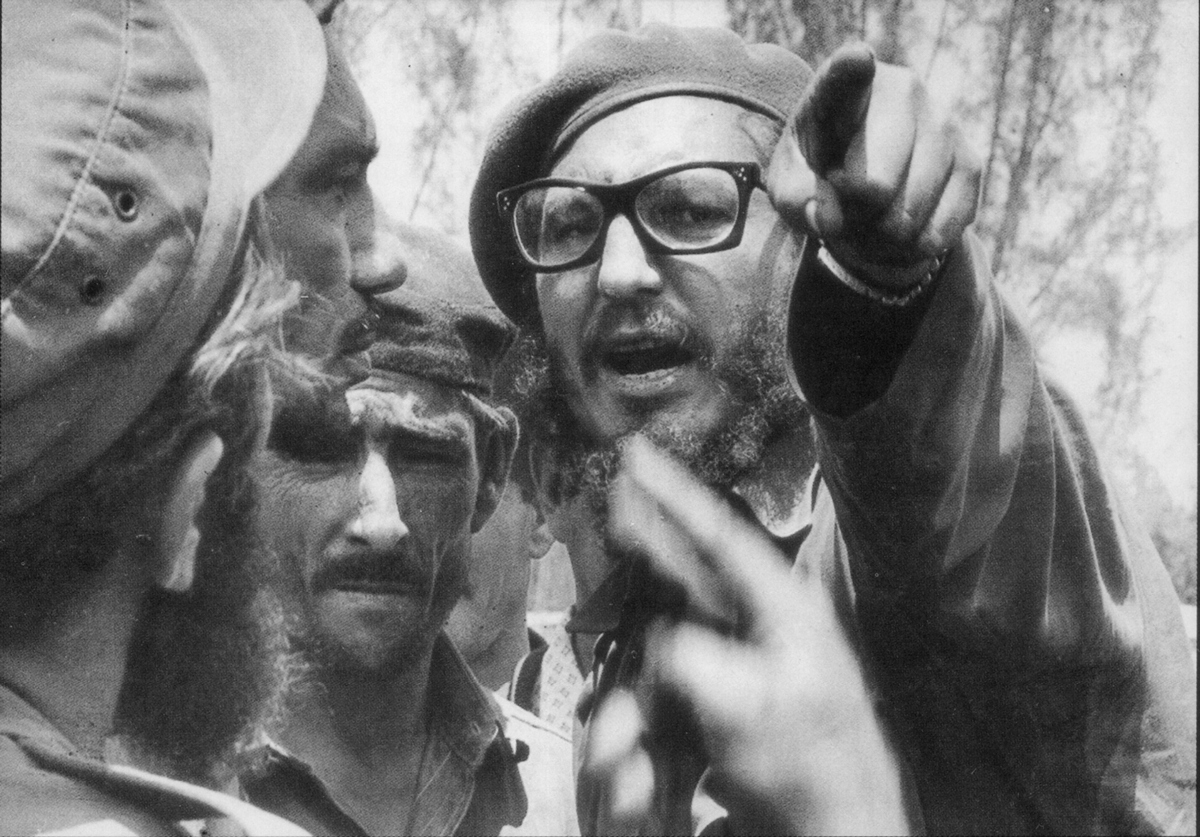

Fidel and Raúl Castro and Che Guevara in photo which appears on

cover of

Cien Imagenes de

la Revolucion Cubana

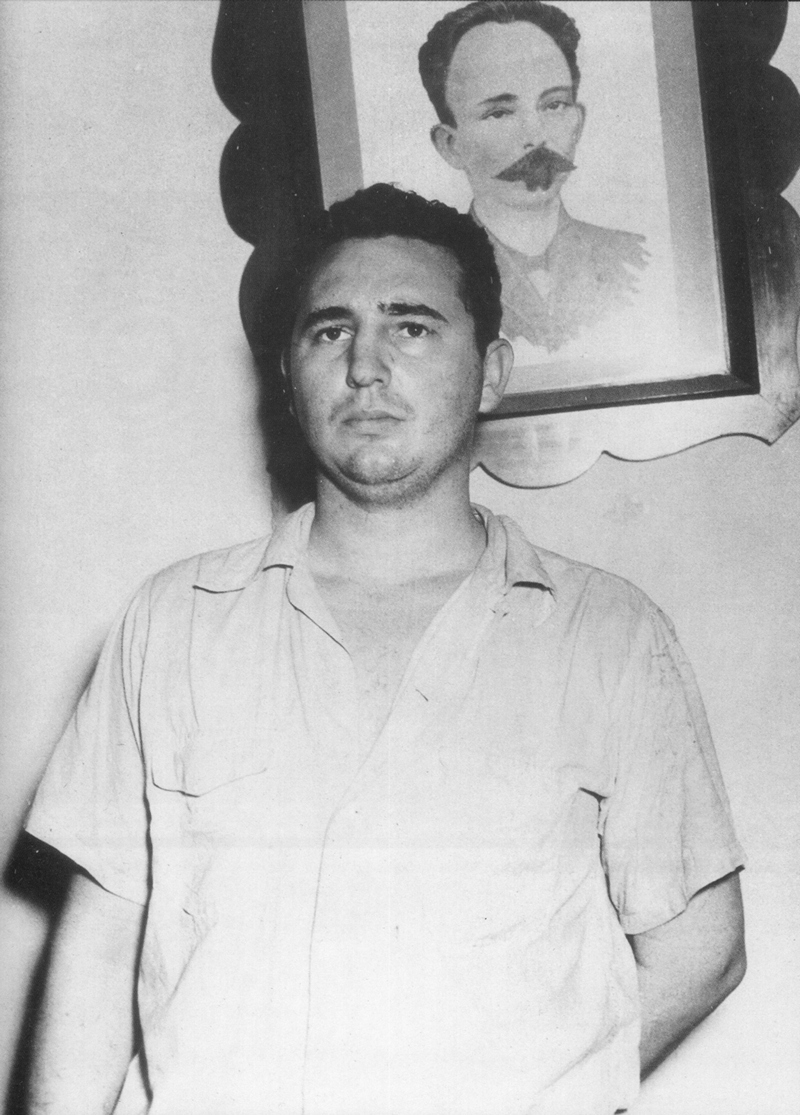

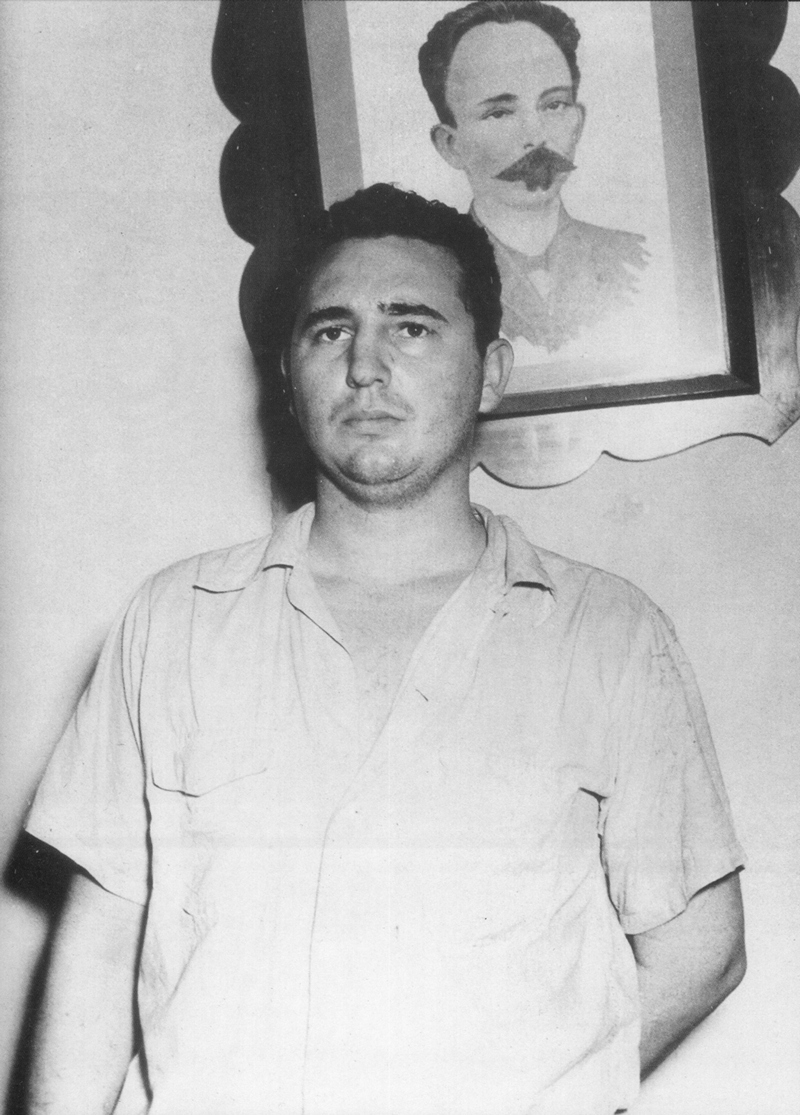

This gallery opens with a shot of concentrated

intensity:

August 1, 1953 a young Fidel Castro appears in La Vivac [prison]

in Santiago de Cuba, and behind him on the wall, in an

inexplicable coincidence that his jailers were unable to avoid,

looms the face of Martí. The last photo, dated May 1, 1996,

captures the crowd in Revolution Square in Havana through a ray of

light, as if the contained energy of the initial image had burst out

and was being manifested in that public space.

|

Fidel Castro, Vivac Prison, 1953

|

Altogether the photos cover four decades in which

the

history of Cuba seems to intensify and move at a faster pace, with

symbols and legends marking every moment: four decades in which

Cubans have given themselves body and soul, without any pettiness, to

an

adventure of transformation, combat and

creation, where the personal route of each has become

incorporated into the collective journey, and they have faced the

impossible without fear, over and over again, conquered their

many demons and put into that hard, heady and full life, that

unique life, the very best of themselves.

In January 1960 Nicolás Guillén confessed

to being perplexed

by the curious quality that time took on in that first year of

the victorious Revolution: '59 passed "as fast as lightning," but

was made up of "pregnant" and "compact" days. In just twelve months

there

was

something substantial that had changed in the air, on the land

of the island, and especially in its people: "We are witnessing

the birth of a new sensibility, rooted in an uncommon conception

of civic duty" the poet tells us, and it is a sensibility that is

manifested in another way of practicing cubanía, of

understanding patriotism, of engaging in private and public

honesty.

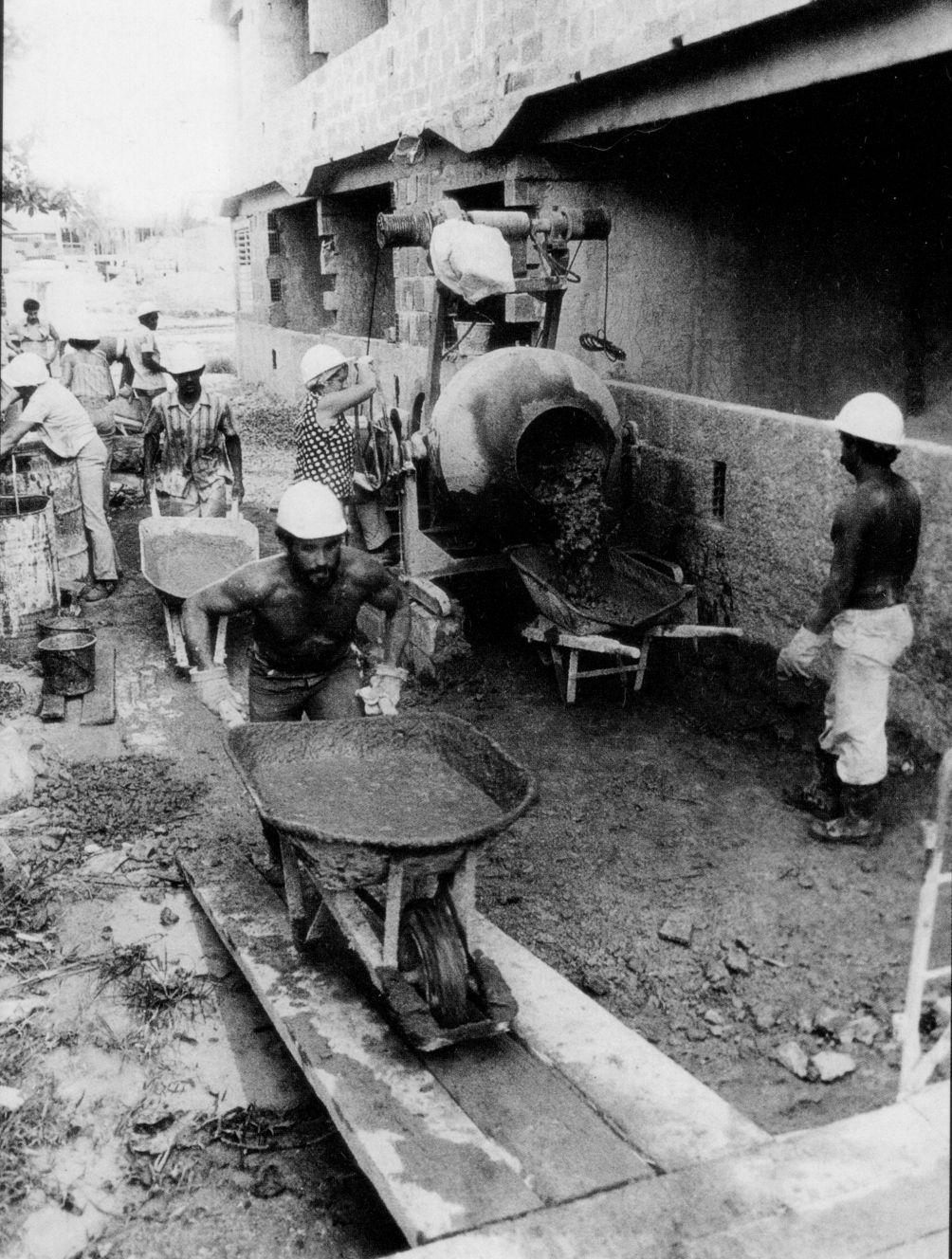

The people who we discover in these pictures, in the

trenches, in the harvest, in volunteer work, in marches and

rallies, bring with them (and it is a hidden privilege that

the photographers managed to capture) a very precise,

well-defined consciousness of the significance of their actions,

of the greater coherence that individuals, their ideals and their

works, take on when a true Revolution is undertaken. They are

radically changing the destiny of an island that seemed doomed to

debasement and disintegration, and at the same time they

understand that it involves a major war, a duel with the

impossible that goes beyond the island's borders. "Every man,"

points out Nicholás, "every woman and even every child knows

what

they have in their hands and is of no mind to let it be snatched from

them."[1]

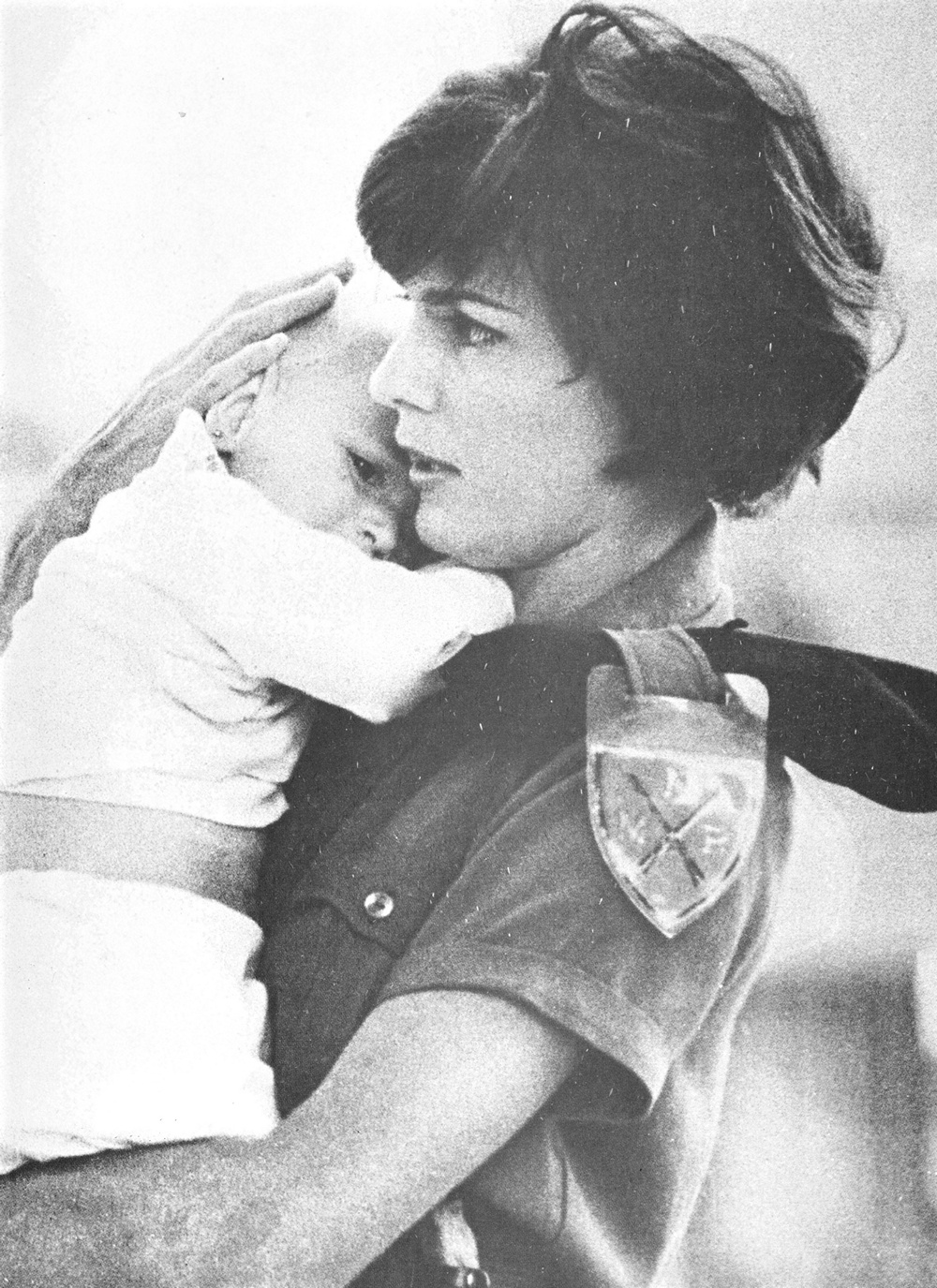

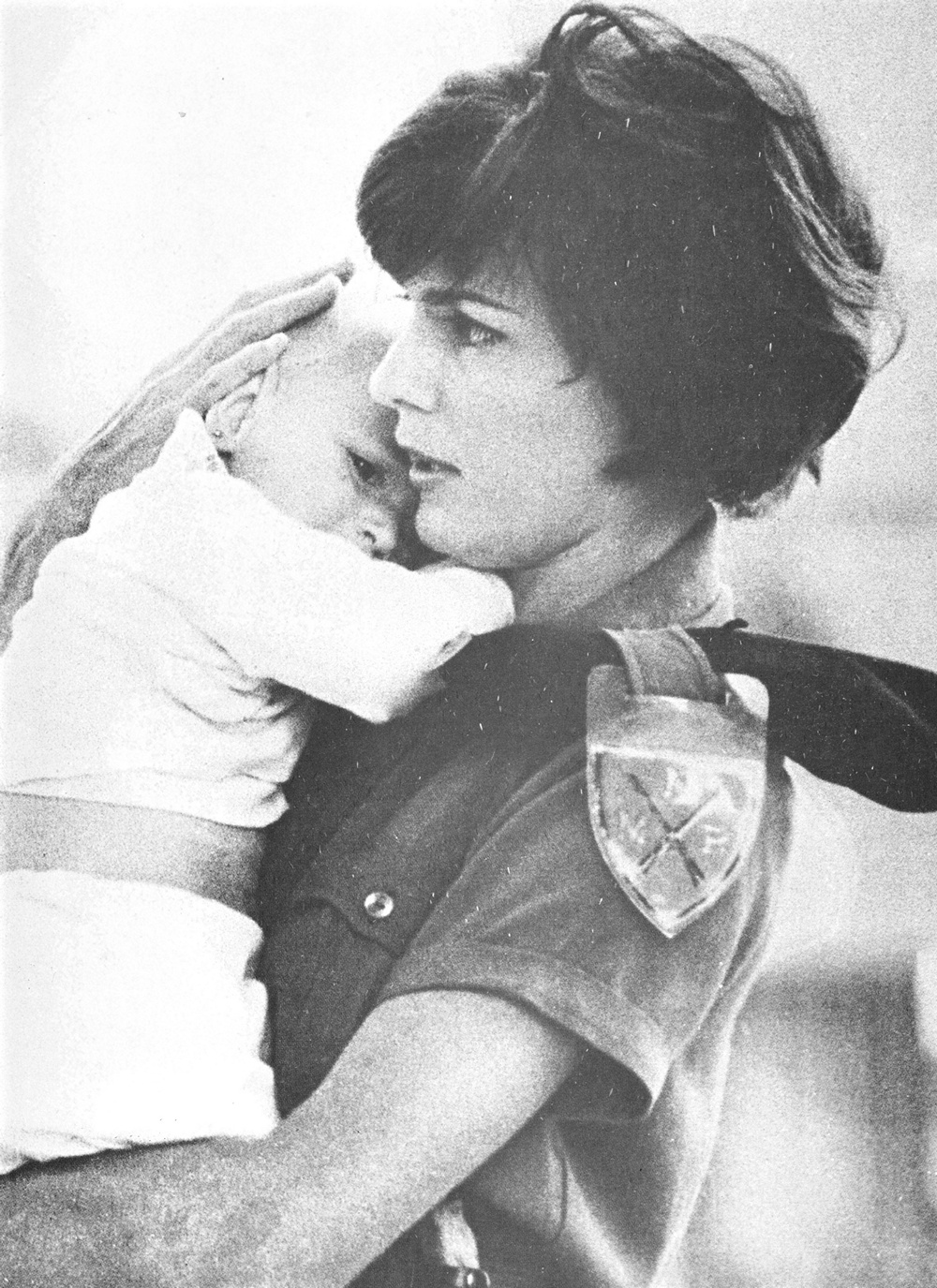

A curious synthesis between political commitment and

other

areas of humanity are externalized in many of the photos that comprise

our gallery: the protagonists of these images show themselves in

their multiple dimensions, in their completeness. You have (to

explain it better and more eloquently) the uniformed militiawoman

carrying her son with the utmost tenderness imaginable, and the

wedding of the militiaman, smiling at the jokes of his

compañeros, at the risks and hardships awaiting him in some

camp,

and at History with a capital H as well as his personal history

(or are they one and the same?) as he passes arm in arm with his

bride under an archway of guns.

The Cuban of the '60s becomes better, more complete,

and is uplifted with happiness at his own condition. We see him grow in

these pictures, not only politically; we see him achieve a dignified

and human dimension he had not known before. We see how the sparkle in

his eye (that spark of feeling, of quick-wittedness, of insight)

becomes more transparent, sharper and dignified. We will not find

frozen, papier maché heroes in our hundred photos: at every step

we are struck by the authenticity, the strength, the vibration that

comes from within to the surface, from deep down to behaviour.

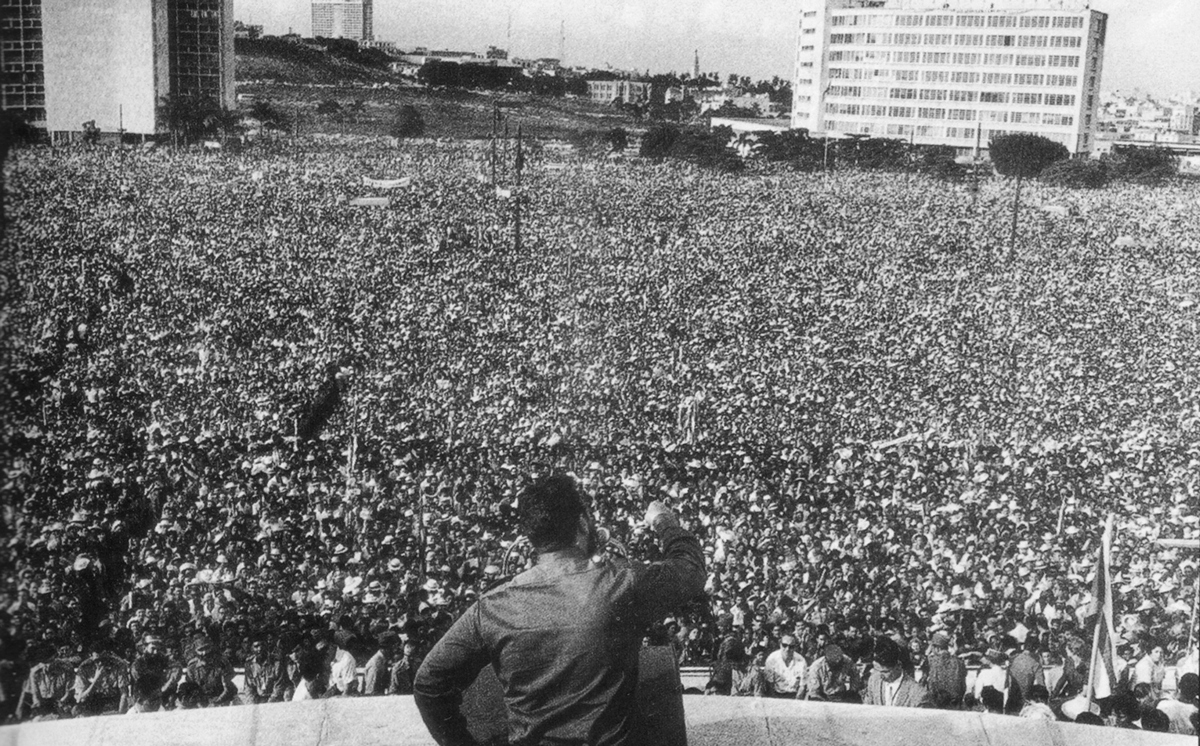

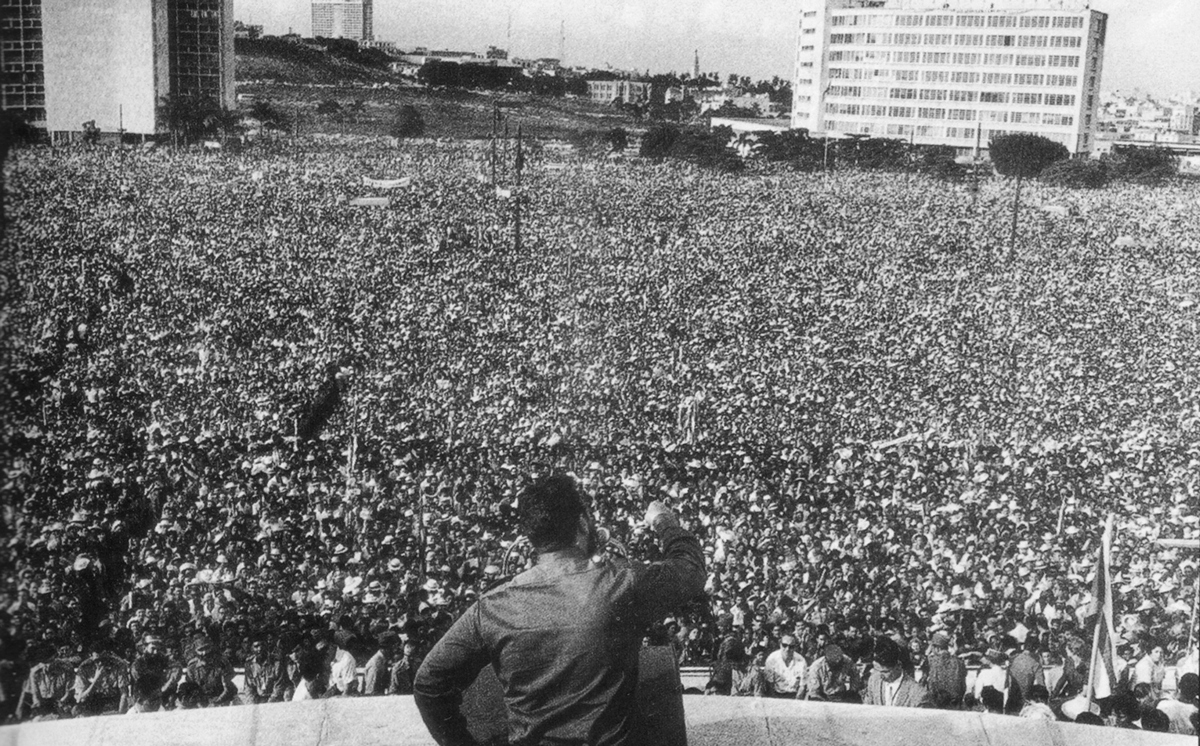

First Declaration of Havana, Speech by Fidel Castro, Revolution Square,

September 2, 1960.

In this gallery the growth of the Cuban is presented to

us in

two ways: in the expressions, the gestures, the demeanour of

anonymous characters caught by the camera, and the multitudinous

acts that lend weight and meaning to a new symbolic space born in

1959: what was Civic Square in the colonial days of farce, crime

and the negation of public spirit is re-baptized José

Martí

Revolution Square and becomes an exceptional arena of exchange

between the popular masses and their leaders. Che left us a

description of that "almost intuitive method" of

communication:

"The master of it is Fidel,

whose particular way of

integrating with the people can be appreciated only by seeing him

in action. In large public gatherings you can observe something

like the dialogue of two tuning forks whose vibrations induce

other, new ones in each other. Fidel and the mass of people begin

to vibrate in a dialogue of increasing intensity until it comes

to a climax in an abrupt ending crowned with our battle cries and

shouts of victory."[2]

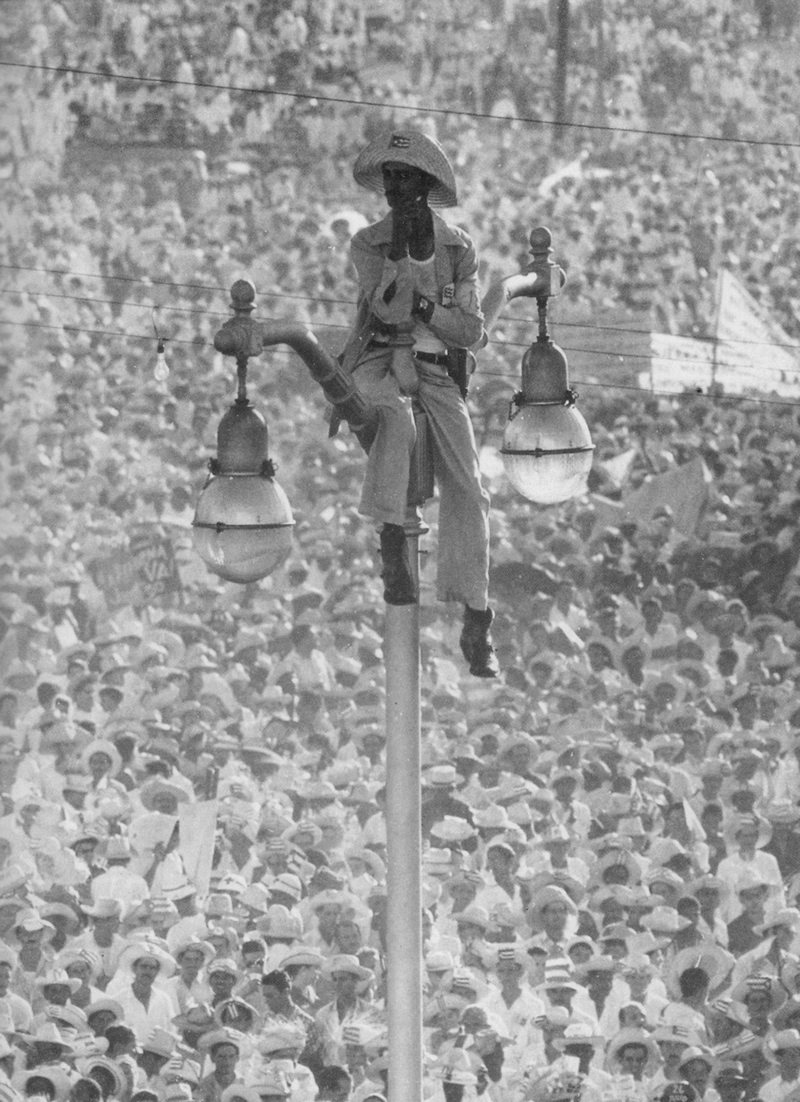

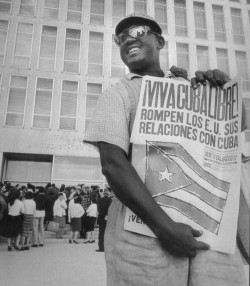

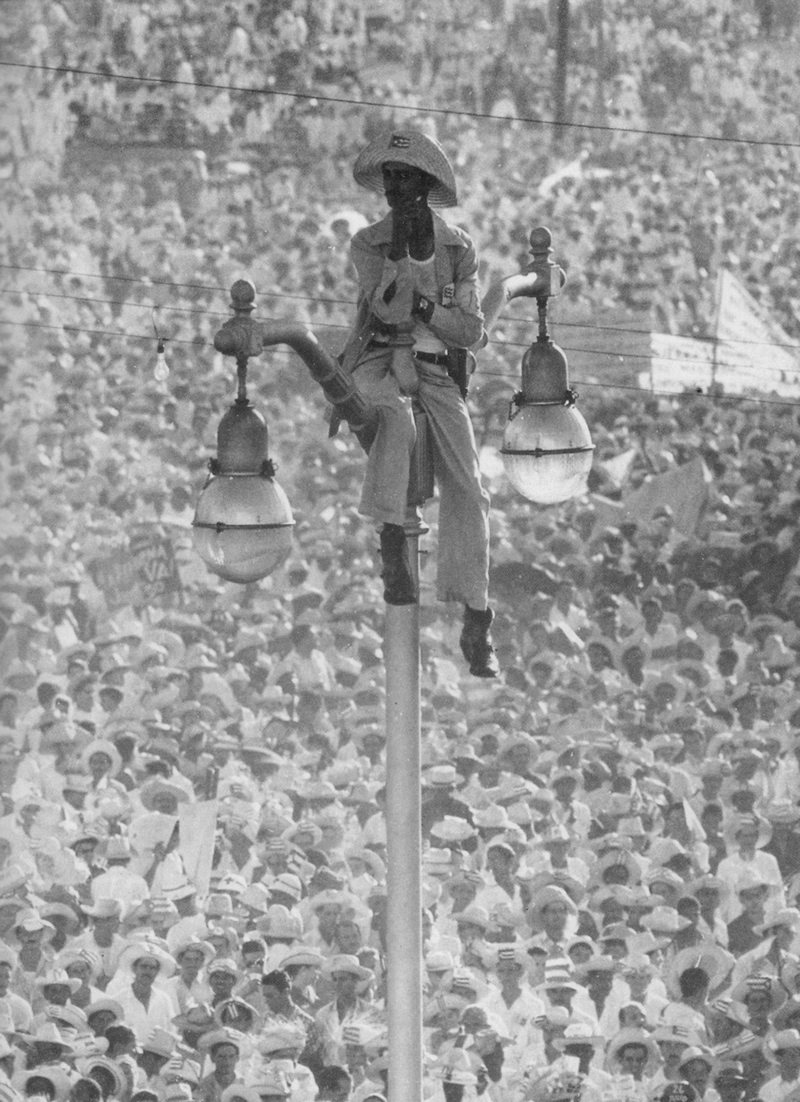

The Korda photo titled El

Quijote de la farola [Quixote of

the Street Lamp] picks up a scene from July 26, 1959, and tells us

something more. About two months earlier, in La Plata, in the

Sierra Maestra, Fidel and the Council of Ministers signed the

Agrarian Reform Law, and now the first mass rally to commemorate

the assault on the Moncada has been organized. Havana and

Revolution Square are filled with campesinos who have come from

all over the island. As in the best of our hundred images, the

Quixote in the straw hat who reigns above the crowd with his

gangly, lanky figure, half-smoked cigar and the expression of one

who lives in harmony with himself and his destiny, draws us to

the specific circumstances (the gathering of peasants, the

Agrarian Reform) and at the same time conjures up a metaphor that

goes beyond the situation and the characters photographed. The Korda photo titled El

Quijote de la farola [Quixote of

the Street Lamp] picks up a scene from July 26, 1959, and tells us

something more. About two months earlier, in La Plata, in the

Sierra Maestra, Fidel and the Council of Ministers signed the

Agrarian Reform Law, and now the first mass rally to commemorate

the assault on the Moncada has been organized. Havana and

Revolution Square are filled with campesinos who have come from

all over the island. As in the best of our hundred images, the

Quixote in the straw hat who reigns above the crowd with his

gangly, lanky figure, half-smoked cigar and the expression of one

who lives in harmony with himself and his destiny, draws us to

the specific circumstances (the gathering of peasants, the

Agrarian Reform) and at the same time conjures up a metaphor that

goes beyond the situation and the characters photographed.

With a quixotic campesino planted for eternity atop a

lamp

post, the gentleman of the utopias, the knight on an unsightly

skinny nag who attacks injustice and the impossible in an unequal

fight with the weapons of his great-grandfathers and a cardboard

trap, enters the book and must undo the schemes of so many

priests, barbers and bachelors who want to tie him (tie us) to

conformism, to the philosophy of submission, to the mediocre

wisdom of half-wits and those of mutilated spirit.

There is a lot of non-conformist, combative quixotism

in the

Cuba that defends her rights against all odds. The National

Press, founded in 1960, was inaugurated with the publication of

400,000 copies of The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of

La Mancha, in four volumes, which were sold (twenty-five

cents each) in newsstands. In this way the people who were able

to overcome another impossible, illiteracy, could read the

immortal novel by Cervantes, and the last knight-errant became a

familiar presence among us. Rarely has a great literary work had

such a rich, prolific and mass reception. "Once again I feel the

ribs of Rocinante under my heels," announces Che to his parents

before leaving for the Congo: "I am returning to the road, with

my shield on my arm."[3]

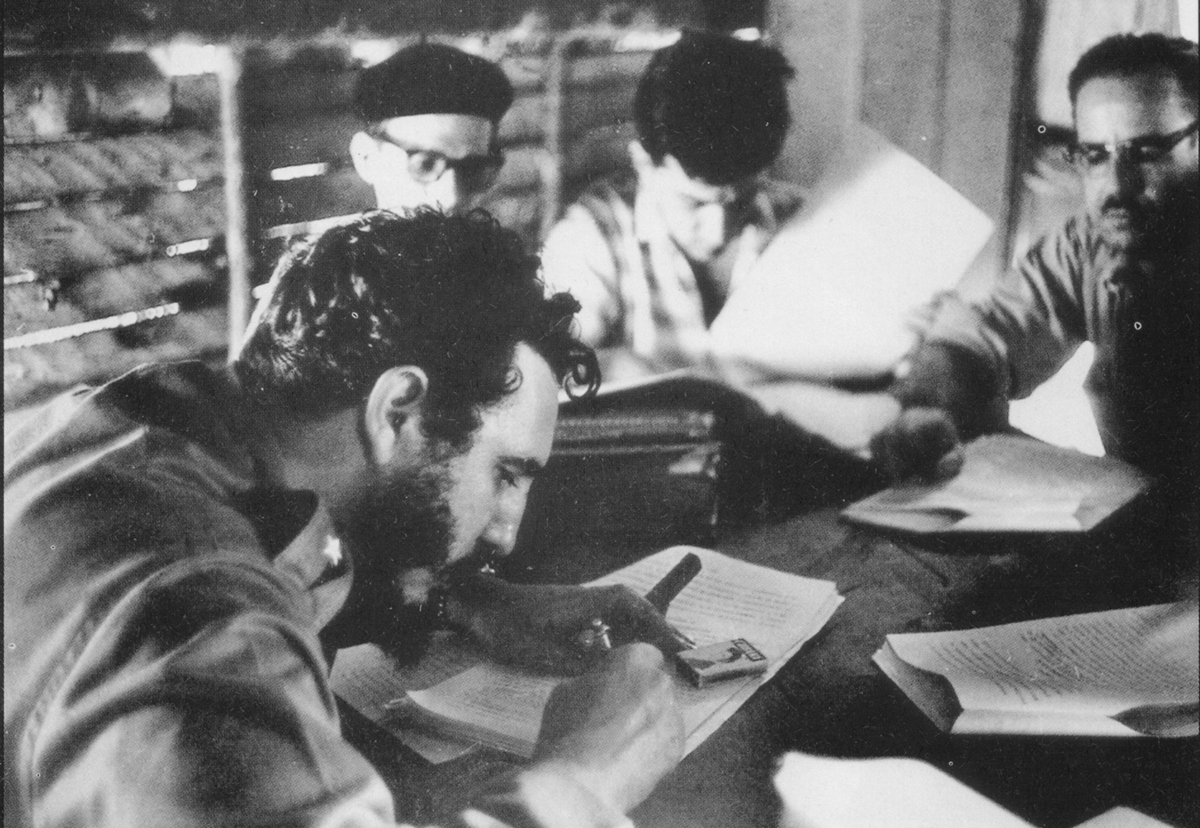

Fidel signs the Agrarian Reform Law in the Sierra Maestra in 1959.

If in the name of the meek ox who every morning chooses

without question the yoke and the delicious, bountiful oats, if

in the name of bourgeois good sense being a "Quixote" is equal to

the worst of insults, the Revolution assumes that symbol

naturally, in its noblest and most creative sense. On the

strength of the No that keeps

appearing in the Cuban ethical

tradition, in the No that