|

November 5, 2016 - No. 43 Supplement Join the Balfour

Declaration  • New

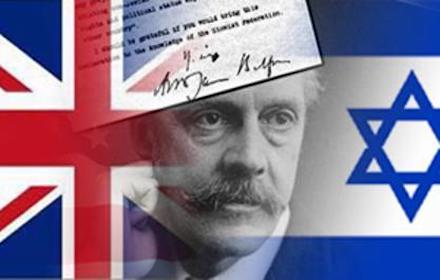

Statesman Editorial, November 1917 99th Anniversary of Balfour Declaration Join the Balfour Declaration Centenary Campaign!November 2 marks the 99th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, a 1917 letter sent by the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to a prominent British Zionist leader promising land in Palestine for foreign settlement. This criminal act of the British Empire to "give" the land of another people usurped during the First World War for colonial settlement created the conditions for countless atrocities against the Palestinians, as well as the subsequent proclamation of a Zionist state and the ongoing genocide and seizure of Palestinian land. Work is underway in many countries to prepare for the centenary in 2017. In considering the crime the British committed it is important to keep in mind the aims of the British Empire at the time and its geopolitical strategy. British Prime Minister Lloyd George and his Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill informed the head of the Zionist Federation Chaim Weizmann in 1921 "that by the Declaration they had always meant an eventual state." To ensure the Zionist minority had the upper hand on behalf of British interests, Lloyd George told Churchill: "You mustn't give representative government to Palestine." Researcher Nu'man Abd al-Wahid noted: "The newly European Jewish settlers were to be the Praetorian Guard of Egypt and specifically of the Suez Canal. As such, in the words of Winston Churchill, European Jews would then 'be especially in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire' rather than 'unassimilated sojourners in every land.'"[1]

The Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist)

condemns the infamous act known as the Balfour Declaration and the

ongoing crimes against the Palestinian people. It is also important to

keep in mind the collusion of successive Canadian governments in

empire-building, the Zionist Project and its wanton aggression and

pre-emptive

wars. In World War I, the Borden government at the request of Lloyd

George facilitated the recruitment in Ontario by David Ben-Gurion for

the "Jewish Legion," which marched into Jerusalem with General Lord

Edmund Allenby’s British Egyptian Expeditionary Force just five weeks

later on December 9, 1917 (Allenby took a stroll in the old walled city

and declared, "Today the Crusades have come to an end.") Centenary Campaign

|

|

|

"The United Kingdom, along with its superpower allies, continues to play a major role by shielding Israel and its settler colonial apparatus, apartheid and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, while granting it legitimacy. This allows Israel to act with impunity and encourages it to continue to deny the Palestinian people their fundamental rights of self-determination and return to their Indigenous homes from which they, or their ancestors, were uprooted in 1948. Today, Britain aids the United States in the perpetuation of neo-colonialism.

"Without the British colonial policies that continued from the so-called British mandate in 1917 until the British withdrawal from Palestine in 1948, the Palestinian 100-year-old catastrophe would have never happened. The British colonial policies included: The ethnic cleansing of about 300,000 Palestinians through expulsion and denial of citizenship; stripping Palestinians of their properties and granting these properties to the colonial settlers; arming and training colonial settlers; crushing any Palestinian resistance with the most horrifying means imagined, and destroying the Palestinian society and its fabric, which eventually resulted in the partition of Palestine and the creation of Israel.

"The catastrophe of the Arab Palestinian people in 1948 continues at the hands of Israel, aided by the United States, using the same old policies and laws established by the British such as land confiscation laws, home demolitions, 'administrative' detention, deportations, violent repression, and the continuation of the expulsion of about 7.9 million Palestinians who are denied their basic national and human rights, especially their right to return and live normally in their homeland.

"And because the catastrophe (nakbah) of the Palestinian people would have never continued without the endless military, diplomatic, economic, and media support of Israel by Britain and the West that goes on until today, we, the Arab Palestinian people in all of Palestine and Diaspora, including all organizations and associations of the Palestinian civil society, call on all the free people of the world and those who believe in human rights, justice, and basic human values to join us in our campaign."

The Balfour Declaration Centenary Campaign can be found at www.bdcc2017.com.

Note

1. Nu'man Abd al-Wahi, "The Empire's Balfour Declaration and the Suez Canal," Churchill's Karma, December 20, 2012.

(Photos: Balfour Declaration Centenary Campaign, Balfour Apology Campaign, O. Aqarbeh, K. Abdelmajeed, I. Hijjawi, Maan News, M. Asad, A. Khalefa)

New Statesman Editorial, November 1917

"The British Government's declaration in favour of Zionism is one of the best pieces of statesmanship that we can show in these latter days. Early in the war the New Statesman published an article giving the main reasons why such a step should be taken, and nothing has occurred to change them. The special interest of the British Empire in Palestine is due to the proximity of the Suez Canal. The present war has killed the idea that this vital artery ought to be used as a line of defence for Egypt, and there is a general return to the view of Napoleon (and indeed of history long before his time) that Egypt must be defended in Palestine. To make Palestine once more prosperous and populous, with a population attached to the British Empire, there is only one hopeful way, and that is to effect a Zionist restoration under British auspices. On the other side of the account it is hard to conceive how anybody with the true instinct for nationality and the desire to see small nations emancipated can fail to be warmed by the prospect of emancipating this most ancient of oppressed nationalities. The present position of the Jews as unassimilated sojourners in every land but their own can never become satisfactory. We know, of course, that a prosperous school of Jewish thought is in favour of treating Judaism as a religion only, and everywhere merging its nationality. But some of these very people are strongest in resisting on religious grounds the intermarriage of Jews with Gentiles, and we fail to see how the adherents of such a distinct religion can ever be really assimilated in other nationalities, so long as by non-intermarriage they keep themselves also a distinct race. It is far better-- without prejudice, of course, to the retention of their existing status by those who prefer it -- to make a nation of them."

(November 7, 1917. The New Statesman is a British political and cultural affairs magazine, founded by prominent members of the Fabian Society in 1913, and which historically has been aligned with the Labour Party)

How Britain Destroyed the Palestinian Homeland

The Road to Nowhere

by Ismail Shammout 1930-2006. He was expelled from

Lydda in 1948. The plight of the refugees is depicted in many of his

most famous paintings. (Displaced

Palestinians)

When I was a child growing up in a Gaza refugee camp, I looked forward to November 2. On that day, every year, thousands of students and camp residents would descend upon the main square of the camp, carrying Palestinian flags and placards, to denounce the Balfour Declaration.

Truthfully, my giddiness then was motivated largely by the fact that schools would inevitably shut down and, following a brief but bloody confrontation with the Israeli army, I would go home early to the loving embrace of my mother, where I would eat a snack and watch cartoons.

At the time, I had no idea who Balfour actually was, and how his "declaration" all those years ago had altered the destiny of my family and, by extension, my life and the lives of my children as well.

All I knew was that he was a bad person and, because of his terrible deed, we subsisted in a refugee camp, encircled by a violent army and by an ever-expanding graveyard filled with "martyrs."

Decades later, destiny would lead me to visit the Whittingehame Church, a small parish in which Arthur James Balfour is now buried.

While my parents and grandparents are buried in a refugee camp, an ever-shrinking space under a perpetual siege and immeasurable hardship, Balfour's resting place is an oasis of peace and calmness. The empty meadow all around the church is large enough to host all the refugees in my camp.

Finally, I became fully aware of why Balfour was a "bad person."

Once Britain's Prime Minister, then the Foreign Secretary from late 1916, Balfour had pledged my homeland to another people. That promise was made on November 2, 1917, on behalf of the British government in the form of a letter sent to the leader of the Jewish community in Britain, Walter Rothschild.

At the time, Britain was not even in control of Palestine, which was still part of the Ottoman Empire. Either way, my homeland was never Balfour's to so casually transfer to anyone else. His letter read:

"His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

He concluded, "I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation."

Ironically, members of the British parliament have declared that the use of the term "Zionist" is both anti-Semitic and abusive.

The British government remains unrepentant after all these years. It has yet to take any measure of moral responsibility, however symbolic, for what it has done to the Palestinians. Worse, it is now busy attempting to control the very language used by Palestinians to identify those who have deprived them of their land and freedom.

But the truth is, not only was Rothschild a Zionist, Balfour was, too. Zionism, then, before it deservedly became a swearword, was a political notion that Europeans prided themselves to be associated with.

In fact, just before he became Prime Minister, David Cameron declared, before the Conservative Friends of Israel meeting, that he, too, was a Zionist. To some extent, being a Zionist remains a rite of passage for some Western leaders.

Balfour was hardly acting on his own. True, the Declaration bears his name, yet, in reality, he was a loyal agent of an empire with massive geopolitical designs, not only concerning Palestine alone, but with Palestine as part of a larger Arab landscape.

Just a year earlier, another sinister document was introduced, albeit secretly. It was endorsed by another top British diplomat, Mark Sykes and, on behalf of France, by François Georges-Picot. The Russians were informed of the agreement, as they too had received a piece of the Ottoman cake.

The document indicated that, once the Ottomans were soundly defeated, their territories, including Palestine, would be split among the prospective victorious parties.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement, also known as the Asia Minor Agreement, was signed in secret 100 years ago, two years into World War I. It signified the brutal nature of colonial powers that rarely associated land and resources with people that lived upon the land and owned those resources.

The centrepiece of the agreement was a map that was marked with straight lines by a china graph pencil. The map largely determined the fate of the Arabs, dividing them in accordance with various haphazard assumptions of tribal and sectarian lines.

1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement Map

Once the war was over, the loot was to be divided into spheres of influence:

- France would receive areas marked (a), which included: the region of south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq -- including Mosel, most of Syria and Lebanon.

- British-controlled areas were marked with the letter (b), which included: Jordan, southern Iraq, Haifa and Acre in Palestine and a coastal strip between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan.

- Russia would be granted Istanbul, Armenia and the strategic Turkish Straits.

The improvised map consisted not only of lines but also colours, along with language that attested to the fact that the two countries viewed the Arab region purely on materialistic terms, without paying the slightest attention to the possible repercussions of slicing up entire civilizations with a multifarious history of co-operation and conflict.

The agreement read, partly:

"... in the blue area France, and in the red area Great Britain, shall be allowed to establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they desire and as they may think fit to arrange with the Arab state or confederation of Arab states."

The brown area, however, was designated as an international administration, the nature of which was to be decided upon after further consultation among Britain, France and Russia. The Sykes-Picot negotiations finished in March 1916 and were official, although secretly signed on May 19, 1916. World War I concluded on November 11, 1918, after which the division of the Ottoman Empire began in earnest.

British and French mandates were extended over divided Arab entities, while Palestine was granted to the Zionist movement a year later, when Balfour conveyed the British government's promise, sealing the fate of Palestine to live in perpetual war and turmoil.

The idea of Western "peacemakers" and "honest-brokers," who are very much a party in every Middle Eastern conflict, is not new. British betrayal of Arab aspirations goes back many decades. They used the Arabs as pawns in their Great Game against other colonial contenders, only to betray them later on, while still casting themselves as friends bearing gifts.

Nowhere else was this hypocrisy on full display as it was in the case of Palestine. Starting with the first wave of Zionist Jewish migration to Palestine in 1882, European countries helped to facilitate the movement of illegal settlers and resources, where the establishment of many colonies, large and small, was afoot.

So when Balfour sent his letter to Rothschild, the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine was very much plausible.

Still, many supercilious promises were being made to the Arabs during the Great War years, as self-imposed Arab leadership sided with the British in their war against the Ottoman Empire. Arabs were promised instant independence, including that of the Palestinians.

The understanding among Arab leaders was that Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations was to apply to Arab provinces that were ruled by the Ottomans. Arabs were told that they were to be respected as "a sacred trust of civilization," and their communities were to be recognised as "independent nations."

Palestinians wanted to

believe that they were also

included

in that civilization sacredness, and were deserving of

independence, too. Their conduct in support of the Pan-Arab

Congress, as voting delegates in July 1919, which elected Faisal

as a King of a state comprising Palestine, Lebanon, Transjordan

and Syria, and their continued support of Sharif Hussein of

Mecca, were all expressions of their desire for the long-coveted

sovereignty.

Palestinians wanted to

believe that they were also

included

in that civilization sacredness, and were deserving of

independence, too. Their conduct in support of the Pan-Arab

Congress, as voting delegates in July 1919, which elected Faisal

as a King of a state comprising Palestine, Lebanon, Transjordan

and Syria, and their continued support of Sharif Hussein of

Mecca, were all expressions of their desire for the long-coveted

sovereignty.

When the intentions of the British and their rapport with the Zionists became too apparent, Palestinians rebelled, a rebellion that has never ceased, 99 years later, for the horrific consequences of British colonialism and the eventual complete Zionist takeover of Palestine are still felt after all these years.

Paltry attempts to pacify Palestinian anger were to no avail, especially after the League of Nations Council in July 1922 approved the terms of the British Mandate over Palestine -- which was originally granted to Britain in April 1920 -- without consulting the Palestinians at all, who would disappear from the British and international radar, only to reappear as negligible rioters, troublemakers, and obstacles to the joint British-Zionist colonial concoctions.

Despite occasional assurances to the contrary, the British intention of ensuring the establishment of an exclusively Jewish state in Palestine was becoming clearer with time.

The Balfour Declaration was hardly an aberration, but had, indeed, set the stage for the full-scale ethnic cleansing that followed, three decades later.

In his book, Before Their Diaspora, Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi captured the true collective understanding among Palestinians regarding what had befallen their homeland nearly a century ago:

"The Mandate, as a whole, was seen by the Palestinians as an Anglo-Zionist condominium and its terms as [an] instrument for the implementation of the Zionist programme; it had been imposed on them by force, and they considered it to be both morally and legally invalid. The Palestinians constituted the vast majority of the population and owned the bulk of the land. Inevitably, the ensuing struggle centred on this status quo. The British and the Zionists were determined to subvert and revolutionise it, the Palestinians to defend and preserve it."

In fact, that history remains in constant replay: The Zionists claimed Palestine and renamed it "Israel;" the British continue to support them, although never ceasing to pay lip service to the Arabs; the Palestinian people remain a nation that is geographically fragmented between refugee camps, in the diaspora, militarily occupied, or treated as second-class citizens in a country upon which their ancestors dwelt since time immemorial.

While Balfour cannot be blamed for all the misfortunes that have befallen Palestinians since he communicated his brief but infamous letter, the notion that his "promise" embodied -- that of complete disregard of the aspirations of the Palestinian Arab people -- is handed from one generation of British diplomats to the next, the same way that Palestinian resistance to colonialism is also spread across generations.

In his essay in the Al-Ahram Weekly, entitled "Truth and Reconciliation," the late Professor Edward Said wrote: "Neither the Balfour Declaration nor the Mandate ever specifically concede that Palestinians had political, as opposed to civil and religious, rights in Palestine.

"The idea of inequality between Jews and Arabs was, therefore, built into British -- and, subsequently, Israeli and U.S. -- policy from the start."

That inequality continues, thus the perpetuation of the conflict. What the British, the early Zionists, the Americans and subsequent Israeli governments failed to understand, and continue to ignore at their own peril, is that there can be no peace without justice and equality in Palestine; and that Palestinians will continue to resist, as long as the reasons that inspired their rebellion nearly a century ago, remain in place.

Ninety-nine years later, the British government is yet to possess the moral courage to take responsibility for what their government has done to the Palestinian people.

Ninety-nine years later, Palestinians insist that their rights in Palestine cannot be dismissed, neither by Balfour, nor by his modern peers in "Her Majesty's Government."

(Al-Jazeera News, November 2, 2016)

The Most Infamous Act

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 was then,

and continues to

be the most infamous act of the British empire. Writing on the

occasion of the anniversary, Stuart Littlewood points out that this

declaration

"began the still-ongoing colonisation of Palestine and sowed the

seeds of an endless nightmare for the Palestinian people, both

those who were forced to flee at gunpoint and those who have

managed to remain in the shredded remains of their homeland under

Israel's brutal military occupation."[1]

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 was then,

and continues to

be the most infamous act of the British empire. Writing on the

occasion of the anniversary, Stuart Littlewood points out that this

declaration

"began the still-ongoing colonisation of Palestine and sowed the

seeds of an endless nightmare for the Palestinian people, both

those who were forced to flee at gunpoint and those who have

managed to remain in the shredded remains of their homeland under

Israel's brutal military occupation."[1]

Stuart Littlewood substantiates the events which set the stage for a century of ethnic cleansing and denial of Palestinian rights. TML Weekly is providing an extract of his account of how this tragedy "was allowed to overtake the Palestinians."

***

For

centuries long our land enslaved

by Turkish

kings

with sharpened blade.

We

prayed to end the Sultan's curse,

the British came and

spoke a verse.

"It's

World War One, if you agree

to fight with us we'll set

you free."

The war

we fought at Britain's side,

our blood was shed for

Arab pride.

our only gain, the lies of Britain.

Stephen Ostrander's simple verse manages to cut through a mountain of rhetoric to the root cause of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

There was a Jewish state in the Holy Land some 3,000 years ago, but the Canaanites and Philistines were there first. The Jews, one of several invading groups, left and returned several times, and were expelled by the Roman occupation in 70AD and again in 135AD. Since the 7th century Palestine has been mainly Arabic. During the First World War the country was 'liberated' from Turkish Ottoman rule after the Allied Powers, in correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and Sharif Hussein ibn Ali of Mecca in 1915, promised independence to Arab leaders in return for their help in defeating Germany's ally.

At the same time, however, a new Jewish political movement called Zionism was finding favour among the ruling elite in London, and the British Government was persuaded by the Zionists' chief spokesman, Chaim Weizman, to surrender Palestine for their new Jewish homeland. Hardly a thought, it seems, was given to the earlier pledge to the Arabs, who had occupied and owned the land for 1,500 years -- longer, say some scholars, than the Jews ever did.

The Zionists, fuelled by

the notion that an ancient Biblical

prophecy gave them the title deeds, aimed to push the Arabs out

by inserting millions of Eastern European Jews. They had already

set up farm communities and founded a new city, Tel Aviv, but by

1914 Jews numbered only 85,000 to the Arabs' 615,000. The

infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917 -- actually a letter from

the British foreign secretary, Lord Balfour, to the most senior

Jew in England, Lord Rothschild -- pledged assistance for the

Zionist cause with apparent disregard for the consequences to the

native majority. Calling itself a "declaration of sympathy with

Jewish Zionist aspirations," it said:

The Zionists, fuelled by

the notion that an ancient Biblical

prophecy gave them the title deeds, aimed to push the Arabs out

by inserting millions of Eastern European Jews. They had already

set up farm communities and founded a new city, Tel Aviv, but by

1914 Jews numbered only 85,000 to the Arabs' 615,000. The

infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917 -- actually a letter from

the British foreign secretary, Lord Balfour, to the most senior

Jew in England, Lord Rothschild -- pledged assistance for the

Zionist cause with apparent disregard for the consequences to the

native majority. Calling itself a "declaration of sympathy with

Jewish Zionist aspirations," it said:

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing and non-Jewish communities...."

Balfour, a Zionist convert, later wrote:

"In Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country. The four powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now occupy that land."

There was opposition. Lord Sydenham warned: "The harm done by dumping down an alien population upon an Arab country may never be remedied. What we have done, by concessions not to the Jewish people but to a Zionist extreme section, is to start a running sore in the East, and no-one can tell how far that sore will extend."

The American King-Crane Commission of 1919 thought it a gross violation of principle. "No British officers consulted by the Commissioners believed that the Zionist programme could be carried out except by force of arms. That, of itself, is evidence of a strong sense of the injustice of the Zionist programme."

There were other reasons why the British were courting disaster. A secret deal, called the Sykes-Picot Agreement, had been concluded in 1916 between France and Britain, in consultation with Russia, to re-draw the map of the Middle Eastern territories won from Turkey. Britain was to take Jordan, Iraq and Haifa. The area now referred to as Palestine was declared an international zone. The Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Balfour Declaration and the promises made earlier in the McMahon-Hussein letters all cut across each other. [...]

The Zionist Organization asked permission to submit its

proposal for Palestine to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference,

hitching a ride on the British request to be granted a mandate

over Palestine in order to implement the Balfour Declaration. The

Zionist case included the statement that "the land itself needs

redemption. Much of it is left desolate. Its present condition is

a standing reproach. Two things are necessary for that redemption

-- a stable and enlightened government, and an addition to the

present population which shall be energetic, intelligent, devoted

to the country, and backed by the large financial resources that

are indispensable for development. Such a population the Jews

alone can supply."

Demonstration in Jerusalem in 1920 in favour of a Damascus-led Arab

nation.

Prominent U.S. Jews opposed to this move handed President Woodrow Wilson a counter-statement objecting to the Zionists' plan, and asked him to present it to the peace conference. It said the scheme to reorganise the Jews as a national unit with territorial sovereignty in Palestine "not only misrepresents the trend of the history of the Jews, who ceased to be a nation 2,000 years ago, but involves the limitation and possible annulment of the larger claims of Jews for full citizenship and human rights in all lands in which those rights are not yet secure. For the very reason that the new era upon which the world is entering aims to establish government everywhere on principles of true democracy, we reject the Zionistic project of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine."

Foreseeing the future with uncanny accuracy, it went on to say, "We rejoice in the avowed proposal of the Peace Congress to put into practical application the fundamental principles of democracy. That principle, which asserts equal rights for all citizens of a state, irrespective of creed or ethnic descent, should be applied in such a manner as to exclude segregation of any kind, be it nationalistic or other. Such segregation must inevitably create differences among the sections of the population of a country. Any such plan of segregation is necessarily reactionary in its tendency, undemocratic in spirit and totally contrary to the practices of free government, especially as these are exemplified by our own country."

The counter-statement quoted Sir George Adam Smith, a noted biblical scholar and the acknowledged expert on the region, who had said: "It is not true that Palestine is the national home of the Jewish people and of no other people... It is not correct to call its non-Jewish inhabitants 'Arabs,' or to say that they have left no image of their spirit and made no history except in the great Mosque... Nor can we evade the fact that Christian communities have been [there] as long as ever the Jews were... These are legitimate questions stirred up by the claims of Zionism, but the Zionists have not yet fully faced them."

America, England, France, Italy, Switzerland and all the most advanced nations of the world, it said, are composed of representatives of many races and religions. "Their glory lies in the freedom of conscience and worship, in the liberty of thought and custom which binds the followers of many faiths and varied civilizations in the common bonds of political union.... A Jewish State involves fundamental limitations as to race and religion, else the term 'Jewish' means nothing. To unite Church and State, in any form, as under the old Jewish hierarchy, would be a leap backward of two thousand years.

"We ask that Palestine be constituted as a free and independent state, to be governed under a democratic form of government recognizing no distinctions of creed or race or ethnic descent, and with adequate power to protect the country against oppression of any kind. We do not wish to see Palestine, either now or at any time in the future, organized as a Jewish State."

But Wilson apparently failed to put the document before the Conference.

In 1922 the League of Nations placed Palestine under British mandate, which incorporated the principles of the Balfour Declaration. Jewish immigration would be facilitated "under suitable conditions" and a nationality law would allow Jews taking up permanent residence to acquire Palestinian citizenship (in sharp contrast to the Jews-only law now operated by a dominant Israel). But the high commissioner was soon recommending a halt to Jewish immigration for fear that it would create a class of landless Arabs. That same year the British government, aware of Arab concerns that the Balfour Declaration was being interpreted in an "exaggerated" way by Zionists and their sympathisers, issued a White Paper to clarify the position.

"The terms of the Declaration referred to," it said, "do not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded 'in Palestine.' In this connection it has been observed with satisfaction that at a meeting of the Zionist Congress, the supreme governing body of the Zionist Organization, held at Carlsbad in September, 1921, a resolution was passed expressing as the official statement of Zionist aims the determination of the Jewish people to live with the Arab people on terms of unity and mutual respect, and together with them to make the common home into a flourishing community, the upbuilding of which may assure to each of its peoples an undisturbed national development...

"It is also necessary to point out that the Zionist Commission in Palestine, now termed the Palestine Zionist Executive, has not desired to possess, and does not possess, any share in the general administration of the country. Nor does the special position assigned to the Zionist Organization in Article IV of the Draft Mandate for Palestine imply any such functions. That special position relates to the measures to be taken in Palestine affecting the Jewish population, and contemplates that the organization may assist in the general development of the country, but does not entitle it to share in any degree in its government.

"Further, it is contemplated that the status of all citizens of Palestine in the eyes of the law shall be Palestinian, and it has never been intended that they, or any section of them, should possess any other juridical status.

"It is necessary," said the White Paper with masterly ambiguity, "that the Jewish community in Palestine should be able to increase its numbers by immigration. This immigration cannot be so great in volume as to exceed whatever may be the economic capacity of the country at the time to absorb new arrivals. It is essential to ensure that the immigrants should not be a burden upon the people of Palestine as a whole, and that they should not deprive any section of the present population of their employment."

However, the White Paper flatly denied that a promise had been made to the Arabs ahead of the Balfour Declaration. "It is not the case, as has been represented by the Arab Delegation, that during the war His Majesty's Government gave an undertaking that an independent national government should be at once established in Palestine. This representation mainly rests upon a letter dated the 24th October, 1915, from Sir Henry McMahon, then His Majesty's High Commissioner in Egypt, to the Sharif of Mecca, now King Hussein of the Kingdom of the Hejaz. That letter is quoted as conveying the promise to the Sharif of Mecca to recognise and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty's Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir Henry McMahon's pledge.

"Nevertheless, it is the intention of His Majesty's government to foster the establishment of a full measure of self-government in Palestine. But they are of the opinion that, in the special circumstances of that country, this should be accomplished by gradual stages..."

From then on, the situation would go from bad to worse.

[...]

In 1937 the Peel Commission declared that British promises to Arabs and Zionists were irreconcilable and unworkable. Too late, Britain dropped its commitment to the Zionists and began talking about a Palestinian state with a guaranteed Arab majority and protection for minorities.

The Zionists reacted furiously. Their underground military wing, the Haganah, and other armed groups, unleashed a reign of terror in the run-up to World War II. They continued their attacks on the British after the war and tried to bring in hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees.

In 1946 they blew up the south wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which housed the British mandatory government, killing 91. This terrorist act was ordered by David Ben-Gurion in retaliation for the arrest of Haganah, Irgun and Stern Gang members suspected of attacks on the British. He then thought better of it and cancelled the operation but Menachem Begin, who led the Irgun, went ahead. Both Ben-Gurion and Begin, who had a big price on his head as a wanted terrorist, became Israeli prime ministers.

|

|

Throughout this period the United States were reluctant to allow Jews fleeing Europe to enter the empty spaces of North America, preferring to play the Zionist game and see them funnelled into Palestine. In 1945 the new U.S. president, Harry Truman, offered Arabs this excuse: "I am sorry, gentlemen, but I have to answer to hundreds of thousands of those who are anxious for the success of Zionism; I do not have hundreds of thousands of Arabs among my constituents."

However, Truman was frequently exasperated by the Zionist lobby and on one occasion had a delegation thrown out of the White House for their table-thumping antics. He wrote: "I fear very much that the Jews are like all underdogs. When they get on top they are just as intolerant and cruel as the people were to them when they were underneath."

American author Gore Vidal provided an intriguing insight. "Sometime in the late 1950s, that world-class gossip and occasional historian, John F. Kennedy, told me how, in 1948, Harry S. Truman had been pretty much abandoned by everyone when he came to run for president. Then an American Zionist brought him two million dollars in cash, in a suitcase, aboard his whistle-stop campaign train. 'That's why our recognition of Israel was rushed through so fast.' As neither Jack nor I was an anti-Semite (unlike his father and my grandfather) we took this to be just another funny story about Truman and the serene corruption of American politics."

By now this monster Britain had breathed life into, was

running out of control. The Arabs, tricked and dispossessed, were

outraged. The collision has been fatally damaging to the West's

relationship with Islam ever since. As the violence escalated,

Gandhi was moved to comment: "Palestine belongs to the Arabs in

the same sense that England belongs to the English. ... They [the

Jews] have erred grievously in seeking to impose themselves on

Palestine with the aid of America and Britain and now with the

aid of naked terrorism."

With the mandate about to expire in 1948 an exhausted Britain handed over the problem to the United Nations and prepared to quit the Holy Land, leaving a powder-keg with the fuse fizzing. The newly-formed UN thought it would save the situation by partitioning Palestine into Arab and Jewish states and making Jerusalem an international city. But this gave the Jews 55 per cent of Palestine when they accounted for only 30 per cent of the population. The Arab League and the Palestinians of course rejected it.

The UN Partition of Palestine never did stand close scrutiny. At that time, as some commentators have pointed out, UN members did not include African states, and most Arab and Asian states were still under colonialist regimes. The UN was pretty much a white colonialist club. The Palestinians themselves had no representation and they weren't even consulted.

|

|

This ludicrous carve-up was quickly followed by shameful incidents at Deir Yassin, Lod and Ramle. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were uprooted from their homes and lands and to this day are denied the right to return. They received no compensation, and after their expulsion Jewish militia obliterated hundreds of Arab villages and towns. No sooner had Britain packed her bags than Israel declared statehood on May 14, 1948 and immediately set about expanding control across all of Palestine.

The following day, May 15, is remembered by Palestinians as the Day of al-Nakba (the Catastrophe), which saw the start of a military terror campaign that forced three-quarters of a million Palestinians from their homeland to make room for the new Jewish state. Some 34 massacres were allegedly committed in pursuit of Israel's territorial ambitions.

An event permanently etched on the Palestinian memory is the massacre at Deir Yassin by Zionist terror groups, the Irgun and the Stern Gang. On an April morning in 1948 130 of their commandos carried out a dawn raid on this small Arab town with a population of 750, to the west of Jerusalem. The attack was initially beaten off, and only when a crack unit of the Haganah arrived with mortars were the Arab townsmen overwhelmed. The Irgun and the Stern Gang, smarting from the embarrassment of having to summon help, embarked on a 'clean-up' operation in which they systematically murdered and executed at least 100 residents -- mostly women, children and old people. The Irgun afterwards exaggerated the number, quoting 254, to frighten other Arab towns and villages. The Haganah played down their part in the raid and afterwards said the massacre "disgraced the cause of Jewish fighters and dishonoured Jewish arms and the Jewish flag."

Deir Yassin signaled the ominous beginning of a deliberate programme by Israel to depopulate Arab towns and villages -- and destroy churches and mosques -- to make room for incoming Holocaust survivors and other Jews. In any language it was an exercise in ethnic cleansing, the knock-on effects of which have created an estimated 4 million Palestinian refugees today.

By 1949 the Zionists had seized nearly 80 percent of Palestine, provoking the resistance backlash they so bitterly complain about today. Many Jews condemn the Zionist policy and are ashamed of what has been done in their name.

UN Resolution 194 had called on Israel to let the Palestinians back onto their land. It has been re-passed many times, but Israel is still in breach. The Israelis also stand accused of violating Article 42 of the Geneva Convention by moving settlers into the Palestinian territories it occupies, and of riding roughshod over international law with their occupation of the Gaza Strip and West Bank.

But expulsion and transfer were always a key part of the Zionist plan. According to historian Benny Morris no mainstream Zionist leader was able to conceive of future co-existence without a clear physical separation between the two peoples. David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister, is reported to have said: "With compulsory transfer we have a vast area (for settlement)... I support compulsory transfer. I don't see anything immoral in it."

He showed astonishing candour on another occasion when he remarked: "If I were an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel. We have taken their country. Sure, God promised it to us, but what does that matter to them? Our God is not theirs. We come from Israel, it is true, but 2,000 years ago, and what is that to them? There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault? They only see one thing: we have come here and stolen their country."

General Moshe Dayan, hero of the Six Day War (1967), made it known to Palestinians in the territories that "you shall continue to live like dogs, and whoever wishes, may leave, and we shall see where this process will lead." That appears to have been the general attitude ever since.

In 1967 Israel perceived a number of Arab threats designed to check Zionist ambitions, including a blockade of their Red Sea port. In a series of pre-emptive strikes against Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq, Israel succeeded in doubling the area of land under its control.

Indeed, in the wake of the 1967 Six Day War Israel confiscated over 52 percent of the land in the West Bank and 30 percent of the Gaza Strip, violating both international law and the UN Charter, which says that a country cannot lawfully make territorial gains from war. It was reported that Israel demolished 1,338 Palestinian homes in the West Bank and detained some 300,000 Palestinians without trial.

The UN issued Security Council Resolution 242, stressing "the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war" and calling for "withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict." It was largely ignored, thus guaranteeing further discord in the region.

Israel's most notorious prime minister, Ariel Sharon, made a name for himself in 1953 when his secret death squad, Unit 101, dynamited homes and massacred 69 Palestinian civilians -- half of them women and children -- at Qibya in the West Bank. His troops later destroyed 2,000 homes in the Gaza Strip, uprooting 12,000 people and deporting hundreds of young Palestinians to Jordan and Lebanon.

Then in 1982 he masterminded Israel's invasion of Lebanon, which resulted in a massive death toll of Palestinians and Lebanese, a large proportion being children. An Israeli tribunal found him indirectly responsible for the massacre of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps and removed him from office. But he didn't stay in the background for long.

By the end of 1967 there were just three illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Jerusalem. By the end of 2005 the total was 177. "When we have settled the land," the then chief of staff of the Israeli Defence Force, Rafael Eitan, remarked in 1983, "all the Arabs will be able to do about it will be to scurry around like drugged cockroaches in a bottle."

By 2015 there were 196 illegal Israeli settlements in addition to 232 settler outposts in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, according to the Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem, and upwards of 750,000 settlers residing there. [...]

(Stuart Littlewood, "Despicable

Balfour: A Story of Betrayal," October 29, 2016)

Balfour Declaration and the Creation of

the Kingdom of

Saudi

Arabia

The covert alliance between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Zionist entity of Israel should be no surprise to any student of British imperialism. The problem is the study of British imperialism has very few students. Indeed, one can peruse any undergraduate or post-graduate British university prospectus and rarely find a module in a Politics degree on the British Empire let alone a dedicated degree or Masters degree. Of course if the European-led imperialist carnage in the four years between 1914-1918 tickles your cerebral cells then it's not too difficult to find an appropriate institution to teach this subject, but if you would like to delve into how and why the British Empire waged war on mankind for almost four hundred years you're practically on your own in this endeavour. One must admit, that from the British establishment's perspective, this is a formidable and remarkable achievement.

In late 2014, according to the American journal, Foreign Affairs, the Saudi petroleum Minister, Ali al-Naimi is reported to have said "His Majesty King Abdullah has always been a model for good relations between Saudi Arabia and other states and the Jewish state is no exception." Recently, Abdullah's successor, King Salman expressed similar concerns to those of Israel to the growing agreement between the United States and Iran over the latter's nuclear programme. This led some to report that Israel and [the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia] presented a "united front" in their opposition to the nuclear deal. This was not the first time the Zionists and Saudis have found themselves in the same corner in dealing with a perceived common foe. In North Yemen in the 1960's, the Saudis were financing a British imperialist-led mercenary army campaign against revolutionary republicans who had assumed authority after overthrowing the authoritarian, Imam. Gamal Abdul-Nasser's Egypt militarily backed the republicans, while the British induced the Saudis to finance and arm the remaining remnants of the Imam's supporters. Furthermore, the British organised the Israelis to drop arms for the British proxies in North Yemen, 14 times. The British, in effect, militarily but covertly, brought the Zionists and Saudis together in 1960's North Yemen against their common foe.

However, one must go back to the 1920's to fully appreciate the origins of this informal and indirect alliance between Saudi Arabia and the Zionist entity. The defeat of the Ottoman Empire by British imperialism in World War One, left three distinct authorities in the Arabian peninsula: Sharif of Hijaz: Hussain bin Ali of Hijaz (in the west), Ibn Rashid of Ha'il (in the north) and Emir Ibn Saud of Najd (in the east) and his religiously fanatical followers, the Wahhabis.

Ibn Saud had entered the war early in January 1915 on the side of the British, but was quickly defeated and his British handler, William Shakespeare was killed by the Ottoman Empire's ally Ibn Rashid. This defeat greatly hampered Ibn Saud's utility to the Empire and left him militarily hamstrung for a year.[1] The Sharif contributed the most to the Ottoman Empire's defeat by switching allegiances and leading the so-called 'Arab Revolt' in June 1916 which removed the Turkish presence from Arabia. He was convinced to totally alter his position because the British had strongly led him to believe, via correspondence with Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, that a unified Arab country from Gaza to the Persian Gulf [would] be established with the defeat of the Turks. The letters exchanged between Sharif Hussain and Henry McMahon are known as the McMahon-Hussain Correspondence.

Understandably, the Sharif as soon as the war ended wanted to hold the British to their war time promises, or what he perceived to be their war time promises, as expressed in the aforementioned correspondence. The British, on the other hand, wanted the Sharif to accept the Empire's new reality which was a division of the Arab world between them and the French (Sykes-Picot agreement) and the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, which guaranteed 'a nation for the Jewish people' in Palestine by colonisation with European Jews. This new reality was contained in the British written, Anglo-Hijaz Treaty, which the Sharif was profoundly averse to signing.[2] After all, the revolt of 1916 against the Turks was dubbed the 'Arab Revolt' not the 'Hijazi Revolt.'

Actually, the Sharif let it be known that he [would] never sell out Palestine to the Empire's Balfour Declaration; he [would] never acquiesce to the establishment of Zionism in Palestine or accept the new random borders drawn across Arabia by British and French imperialists. For their part the British began referring to him as an 'obstructionist', a 'nuisance' and of having a 'recalcitrant' attitude.

The British let it be known to the Sharif that they were prepared to take drastic measures to bring about his approval of the new reality regardless of the service that he had rendered them during the War. After the Cairo Conference in March 1921, where the new Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill met with all the British operatives in the Middle East, T.E. Lawrence (i.e. of Arabia) was dispatched to meet the Sharif to bribe and bully him to accept Britain's Zionist colonial project in Palestine. Initially, Lawrence and the Empire offered 80,000 rupees.[3] The Sharif rejected it outright. Lawrence then offered him an annual payment of £100,000.[4] The Sharif refused to compromise and sell Palestine to British Zionism.

When financial bribery failed to persuade the Sharif, Lawrence threatened him with an Ibn Saud takeover. Lawrence claimed that "politically and militarily, the survival of Hijaz as a viable independent Hashemite kingdom was wholly dependent on the political will of Britain, who had the means to protect and maintain his rule in the region."[5] In between negotiating with the Sharif, Lawrence made the time to visit other leaders in the Arabian peninsula and informed them that if they don't toe the British line and avoid entering into an alliance with the Sharif, the Empire will unleash Ibn Saud and his Wahhabis who after all is at Britain's 'beck and call.'[6]

Simultaneously, after the Conference, Churchill travelled to Jerusalem and met with the Sharif's son, Abdullah, who had been made the ruler, "Emir," of a new territory called "Transjordan." Churchill informed Abdullah that he should persuade "his father to accept the Palestine mandate and sign a treaty to such effect," if not "the British would unleash Ibn Saud against Hijaz."[7] In the meantime the British were planning to unleash Ibn Saud on the ruler of Ha'il, Ibn Rashid.

Ibn Rashid had rejected all overtures from the British Empire made to him via Ibn Saud, to be another of its puppets.[8] More so, Ibn Rashid expanded his territory north to the new mandated Palestinian border as well as to the borders of Iraq in the summer of 1920. The British became concerned that an alliance [might] be brewing between Ibn Rashid who controlled the northern part of the peninsula and the Sharif who controlled the western part. More so, the Empire wanted the land routes between the Palestinian ports on the Mediterranean Sea and the Persian Gulf under the rule of a friendly party. At the Cairo Conference, Churchill agreed with an imperial officer, Sir Percy Cox that "Ibn Saud should be 'given the opportunity to occupy Ha'il.'"[9] By the end of 1920, the British were showering Ibn Saud with "a monthly 'grant' of £10,000 in gold, on top of his monthly subsidy. He also received abundant arms supplies, totalling more than 10,000 rifles, in addition to the critical siege and four field guns" with British-Indian instructors.[10] Finally, in September 1921, the British unleashed Ibn Saud on Ha'il which officially surrendered in November 1921. It was after this victory the British bestowed a new title on Ibn Saud. He was no longer to be "Emir of Najd and Chief of its Tribes" but "Sultan of Najd and its Dependencies." Ha'il had dissolved into a dependency of the Empire's Sultan of Najd.

If the Empire thought that the Sharif, with Ibn Saud

now on

his border and armed to the teeth by the British, would finally

become more amenable to the division of Arabia and the British

Zionist colonial project in Palestine [it was] short lived. A

new round of talks between Abdulla's son, acting on behalf of his

father in Transjordan and the Empire resulted in a draft treaty

accepting Zionism. When it was delivered to the Sharif with an

accompanying letter from his son requesting that he "accept

reality," he didn't even bother to read the treaty and instead

composed a draft treaty himself rejecting the new divisions of

Arabia as well as the Balfour Declaration and sent it to London

to be ratified![11]

Abdel Aziz Ibn Saud with Sir Percy Cox

Ever since 1919 the British had gradually decreased Hussain's subsidy to the extent that by the early 1920's they had suspended it, while at the same time [they] continued subsidising Ibn Saud right through the early 1920's.[12] After a further three rounds of negotiations in Amman and London, it dawned on the Empire that Hussain [would] never relinquish Palestine to Great Britain's Zionist project or accept the new divisions in Arab lands.[13] In March 1923, the British informed Ibn Saud that it [would] cease his subsidy but not without awarding him an advance 'grant' of £50,000 upfront, which amounted to a year's subsidy.[14]

In March 1924, a year after the British awarded the 'grant' to Ibn Saud, the Empire announced that it had terminated all discussions with Sharif Hussain to reach an agreement.[15] Within weeks the forces of Ibn Saud and his Wahhabi followers began to administer what the British foreign secretary, Lord Curzon called the "final kick" to Sharif Hussain and attacked Hijazi territory.[16] By September 1924, Ibn Saud had overrun the summer capital of Sharif Hussain, Ta'if. The Empire then wrote to Sharif's sons, who had been awarded kingdoms in Iraq and Transjordan not to provide any assistance to their besieged father or in diplomatic terms they were informed "to give no countenance to interference in the Hedjaz".[17] In Ta'if, Ibn Saud's Wahhabis committed their customary massacres, slaughtering women and children as well as going into mosques and killing traditional Islamic scholars.[18] They captured the holiest place in Islam, Mecca, in mid-October 1924. Sharif Hussain was forced to abdicate and went to exile to the Hijazi port of Akaba. He was replaced as monarch by his son Ali who made Jeddah his governmental base. As Ibn Saud moved to lay siege to the rest of Hijaz, the British found the time to begin incorporating the northern Hijazi port of Akaba into Transjordan. Fearing that Sharif Hussain [might] use Akaba as a base to rally Arabs against the Empire's Ibn Saud, the Empire let it be known, in no uncertain terms, that he must leave Akaba or Ibn Saud [would] attack the port. For his part, Sharif Hussain responded that he had, "never acknowledged the mandates on Arab countries and still protest against the British Government which has made Palestine a national home for the Jews."[19]

Sharif Hussain was forced out of Akaba, a port he had liberated from the Ottoman Empire during the 'Arab Revolt', on 18th June 1925 on HMS Cornflower.

Ibn Saud had begun his siege of Jeddah in January 1925 and the city finally surrendered in December 1925 bringing to an end over 1000 years of rule by the Prophet Muhammad's descendants. The British officially recognised Ibn Saud as the new King of Hijaz in February 1926 with other European powers following suit within weeks. The new unified Wahhabi state was rebranded by the Empire in 1932 as the "Kingdom of Saudi Arabia". A certain George Rendel, an officer working at the Middle East desk at the Foreign Office in London, claimed credit for the new name.

On the propaganda level, the British served the Wahhabi takeover of Hijaz on three fronts. Firstly, they portrayed and argued that Ibn Saud's invasion of Hijaz was motivated by religious fanaticism rather than by British imperialism's geo-political considerations.[20] This deception is propounded to this day, most recently in Adam Curtis's acclaimed BBC "Bitter Lake" documentary, whereby he states that the "fierce intolerant vision of wahhabism" drove the "beduins" to create Saudi Arabia.[21] Secondly, the British portrayed Ibn Saud's Wahhabi fanatics as a benign and misunderstood force who only wanted to bring Islam back to its purest form.[22] To this day, these Islamist jihadis are portrayed in the most benign manner when their armed insurrections are supported by Britain and the West such as 1980's Afghanistan or in today's Syria, where they are referred to in the western media as "moderate rebels." Thirdly, British historians portray Ibn Saud as an independent force and not as a British instrument used to horn away anyone perceived to be surplus to imperial requirements. For example, Professor Eugene Rogan's recent study on the history of Arabs claims that "Ibn Saud had no interest in fighting" the Ottoman Empire. This is far from accurate as Ibn Saud joined the war in 1915. He further disingenuously claims that Ibn Saud was only interested in advancing "his own objectives" which fortuitously always dovetailed with those of the British Empire.[23]

In conclusion, one of the most overlooked aspects of the Balfour Declaration is the British Empire's commitment to "use their best endeavours to facilitate" the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." Obviously, many nations in the world today were created by the Empire but what makes Saudi Arabia's borders distinctive is that its northern and north-eastern borders are the product of the Empire facilitating the creation of Israel. At the very least the dissolution of the two Arab sheikhdoms of Ha'il and Hijaz by Ibn Saud's Wahhabis is based in their leaders' rejection to facilitate the British Empire's Zionist project in Palestine.

Therefore, it is very clear that the British Empire's drive to impose Zionism in Palestine is embedded in the geographical DNA of contemporary Saudi Arabia. There is further irony in the fact that the two holiest sites in Islam are today governed by the Saudi clan and Wahhabi teachings because the Empire was laying the foundations for Zionism in Palestine in the 1920s. Contemporaneously, it is no surprise that both Israel and Saudi Arabia are keen on militarily intervening on the side of "moderate rebels" i.e. jihadis, in the current war on Syria, a country which covertly and overtly rejects the Zionist colonisation of Palestine.

As the United States, the 'successor' to the British Empire in defending western interests in the Middle East, is perceived to be growing more hesitant in engaging militarily in the Middle East, there is an inevitability that the two nations rooted in the Empire's Balfour Declaration, Israel and Saudi Arabia, would develop a more overt alliance to defend their common interests.

Nu'man Abd al-Wahid is a Yemeni-English independent researcher specialising in the political relationship between the British state and the Arab World. His main focus is on how the United Kingdom has historically maintained its political interests in the Arab World. A full collection of essays can be accessed at http://www.churchills-karma.com/. Twitter handle: @churchillskarma.

Notes

1. Gary Troeller, The Birth of Saudi Arabia

(London: Frank Cass,

1976),

pg. 91.

2. Askar H. al-Enazy, The Creation of Saudi Arabia:

Ibn Saud and British Imperial Policy, 1914-1927 (London: Routledge,

2010), pg.

105-106.

3. Ibid, pg. 109.

4. Ibid, pg. 111.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid, pg

107.

8. Ibid., pg. 45-46 and pg.

101-102.

9. Ibid., pg. 104.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid., pg. 113.

12. Ibid., pg. 110 and Troeller, op. cit., pg.

166.

13. al-Enazy op cit., pg. 112-125.

14. al-Enazy, op. cit., pg.

120.

15. Ibid., pg. 129.

16. Ibid., pg. 106 and Troeller

op.

cit., 152.

17. al-Enazy, op. cit., pg. 136

and Troeller op. cit., pg. 219.

18. David Howarth, The Desert King: The Life of Ibn Saud (London: Quartet Books, 1980), pg. 133 and Randall Baker, King Husain and the Kingdom of Hejaz (Cambridge: The Oleander Press, 1979), pg. 201-202.

19. Quoted in al-Enazy op. cit., pg. 144.

20. Ibid., pg. 138 and Troeller

op.

cit., pg. 216.

21. In the original full length BBC iPlayer

version this segment begins towards the end at 2 hrs 12 minutes 24

seconds.

22. al-Enazy op. cit.,

pg. 153.

23. Eugene Rogan, The Arabs: A

History (London: Penguin Books, 2009), pg. 220.

(Churchill's Karma, November 20,

2015/Mondoweiss, January 7, 2016)

A Balfour Curse

Demonstration in Damascus against Balfour's visit to the region in 1925.

It is well-known that Lord Balfour, the British Foreign Office secretary during World War I, issued the notorious declaration on 2 November 1917 in which the British government pledged to assist in the establishment of a homeland for the Jews in Palestine. Lesser known, however, is the story of this man before his name became associated with the document that marked the creation of the state of Israel and the subsequent disasters this wreaked upon the Arabs.

Arthur James Balfour, born in 1848, was almost 70 when he issued the declaration bearing his name. Of Scottish aristocratic origin, he entered the House of Commons in 1885, becoming minister for Scottish affairs the following year and minister for Irish affairs a year later. It was in the latter position that he acquired the nickname that would haunt him for some time, "Bloody Balfour," for his overly zealous enforcement of the Irish Crimes Act issued by the British government to suppress the resistance movement in Ireland.

In 1892, Balfour became head of the opposition to the Liberal government and did not return to the cabinet until 1915, when he became minister of the Navy under the national unity government of Herbert Asquith formed in May that year following a series of setbacks suffered by British forces at the outset of World War I. The following year, when a new cabinet was formed under Lloyd George, Balfour became one of the elder statesmen invited to join the ministry and remained in this position until his resignation in 1922 at the age of 74.

Undoubtedly the elder statesman's contemporaries had imagined that he would live out his remaining years after retirement in the manner of men of his rank and class, pottering around on his country estate and writing his memoirs. Not so Lord Balfour, who could not bring himself to relinquish public life. Still, it is remarkable that three years later, he decided to accept an invitation to attend the opening of the Hebrew University in March 1925, accepting the possible risk to his person now that the victims of his declaration realised the magnitude of his injustice towards them. The invitation was extended to Balfour by one of the founders of the Zionist state, Chaim Weizmann, who hoped to take advantage of the occasion to promote the Jewish national homeland and who had invited for the same purpose a large number of prominent political figures.

Balfour's journey took him first to Egypt where he arrived on the afternoon of Monday 23 March 1925. On hand in the port of Alexandria was Al-Ahram's special correspondent to relay to the newspaper's readers the details of the retired British official's arrival. He reports, "Many Jewish notables in the city along with a Zionist committee and a contingent of students from Jewish schools went to the port to greet Lord Balfour. At 4:00 pm the Esperia docked in the western harbour. The Zionist committee, headed by a rabbi, boarded and after a short while disembarked. The Railways Authority had prepared a special saloon carriage which Lord Balfour and his entourage took to Cairo."

In Cairo, Balfour was the guest of Lord and Lady Allenby. Aside from the diplomatic motives behind the British high commissioner's hospitality, the two men figured prominently in the events of World War I that would shape the future of the region. Allenby had led the military campaign that drove the Turkish armies out of the Levant in 1917 and Balfour issued his disaster-laden pledge that same year. In Alexandria, where Balfour spent just over two hours, the only welcome he received was from the representatives of the Alexandria Jewish community. At 6:00 pm on the following day, Tuesday 25 March, Balfour's delegation, which now included a number of Jewish leaders who had met him in Alexandria, boarded the train bound for Suez and from there to Palestine. To see him off at the station were both Zionists and Palestinians, "the former taking off their hats to him, the latter invoking imprecations against his notorious pledge," as Al-Ahram reported.

Many Egyptians had joined the Palestinians in supporting Arab Palestine. But their joint demonstration was met with unusual brutality by police. Mohamed Ali Taher, owner of Al-Shura newspaper, was among the protesters and gave a first-hand account of the events:

"The Azbakiya police chief ordered his policemen to

drag me

through the streets to the police station rather than be

transported in a guarded police wagon. I was taken to the station

in this degrading manner, with people tagging along around me.

They treated my colleague, Amin Effendi Abdel-Latif El-Husseini,

the brother of the Mufti of Jerusalem, in exactly the same

manner. In the police station, the commissioner refused to simply

write up a report and let us off, even with the payment of a

bond. Rather, he confiscated our personal papers and our

cigarettes and detained us in the holding cell until the

following day."

On this discordant note, Balfour's train set off for Palestine. The journey has been treated in some detail in various historical studies, foremost among which is The Palestinian National Movement: 1917-1936 by Adel Ghoneim. However, the full account as recorded by Al-Ahram merits closer inspection. As the train carrying Balfour made its way towards Palestine, protest letters and telegrams poured into Al-Ahram offices. One sent in the name of the Syrian expatriate community in Egypt and addressed to Balfour announced, "We condemn your iniquitous declaration. We will never relinquish our usurped rights and will pursue our struggle to the end in the hopes of realising our national aspirations." The telegram was signed by more than 20 people, among whom was Shukri Al-Quwatli, who would eventually become president of the Republic of Syria. A second telegram, sent by the Jordanian community in Egypt, reminded Balfour that he was on his way to the country whose "freedom and liberty you have destroyed with your reprehensible declaration," adding that Balfour's arrival "will only augment the Palestinians' devotion to their country."

|

|

No amount of protest, however, was about to dissuade Balfour from his chosen path. Al-Ahram had dispatched another reporter to Jerusalem to cover the British lord's movements from the time his train pulled into the Holy City. Balfour's first official visit was to the Zionist settlement of Qara, where he was accorded "an enthusiastic welcome." Following a luncheon there, Balfour and his entourage went to Tel Aviv, "the modern Jewish city that was constructed near Jaffa." Upon his arrival, the visiting dignitary found "all the houses and institutes bedecked with British and Zionist flags and hordes of people -- men, women and students -- rushing out to greet him carrying banners bearing his picture around their necks." The Al-Ahram correspondent continues, "A force of 150 Jewish youths had volunteered to assist the army and police in maintaining order."

Meanwhile, schools in Gaza and Tulkarm, the Teachers College in Jerusalem and other Palestinian institutes went on strike to protest against Balfour's visit "as people are doing throughout the country." Undoubtedly, the British mandate government in Palestine was prepared for possible unrest, for Al-Ahram reports that the British minister of war had announced to the House of Commons that an armoured cavalry regiment had been sent from Egypt to Palestine to quell any disturbances.

Shortly thereafter, Al-Ahram

reported that the Egyptian

government intended to send Ahmed Lutfi El-Sayyid, director of

the Egyptian National University, to Palestine to attend the

inaugural ceremony of the Hebrew University. To the surprise of

many and despite the outcry of Palestinians in Egypt, the

professor agreed to go. In a letter to Al-Ahram, the Arab Youth

of Palestine protested that El-Sayyid's acceptance of the

invitation was a stab in the back of Arab Palestine and appealed

to the Egyptian government to reverse its decision. Similarly,

Palestinian students at Al-Azhar University expressed sorrow at

the university's decision to send a delegate to the inauguration

because "it will enable Zionists to exploit the name of Egypt on

their behalf." Again, Palestinian protests fell on deaf ears as

the Egyptian university official set off to Palestine to attend

the opening of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, something he

regretted later.

Balfour visits Jewish settlements in Palestine during his 1925 trip.

Back in Palestine, Balfour made his way to another Jewish settlement, as obstinately deaf as ever to Arab and Palestinian grievances and apparently determined to be as provocative as possible. On one occasion he declared he was a close friend of Baron Rothschild and that "if he was not as old a Zionist as the Baron he was, nevertheless, one of the first Zionists." Elsewhere he remarked that his pledge to create a homeland for the Jews in Palestine was "not the plan of a specific person or nation, but rather an embodiment of the view of the greater body of nations that signed the Versailles Treaty and could, therefore, never by nullified."

Balfour spent two weeks in Palestine amidst general

strikes

and protests by Palestinians and jubilation by Zionists who

renamed the street his car passed through in Tel Aviv after him.

His last stop before leaving on 7 April was Haifa where "the

entire city went on strike." Still, he was intent on visiting the

Zionist quarter of the city and various Zionist institutions and

dining with the governor of the city.

British police harass Palestinians.

The next leg of Balfour's tour took him to Syria where he would encounter an entirely different situation. Syria was not subject to British mandate rule, which was ever ready to suppress Palestinian demonstrations. Fired up by its well-known Arab nationalist fervour, Syria was gearing itself for the Great Syrian Revolution that began later that year. And there would be no Zionists in Syria to welcome Balfour.

On the morning of 8 April, the private train carrying Balfour and his entourage set off from Haifa to Damascus amid tight security. "Government officials escorted Balfour to the train, which he boarded along with several British agents who were sent to ensure his safety. Although the British government had positioned police at the stations, this did not prevent villagers from shouting out protests and waving black banners as the train passed through."

British authorities in Palestine also secured an agreement from the French protectorate government in Syria to protect Balfour during his visit. Accordingly, French authorities in Hauran and Der'a secured the train stations in these regions and the French police commandant in Damascus went to the border to greet the train. Al-Ahram goes on to report, "When the train arrived in Der'a French officials were on hand to receive Balfour and invited him and his entourage to a meal in the station restaurant, which the police commandant had cordoned off, after which Balfour reboarded the train on his way to Damascus."

Having sensed the unrest in the Syrian capital because of the impending visit of the author of the notorious declaration, French officials arranged for Balfour to get off the train at a station on the outskirts of the capital rather than in Damascus itself. On hand to greet him was the British consul and other consular officials who had arranged for a sufficient number of cars to transport the visitors. "The cars raced to the Victoria Hotel where private quarters had been set aside for Balfour's visit. They were heavily guarded by police and secret service agents. As no one had been informed of these plans, Balfour arrived without incident."

|

|

However, even as the British statesman was settling down in his room, "a crowd of men of all ages bearing black banners thronged to the Damascus train station. The police forces that had been stationed there prevented people from entering, while another contingent of police guards had been stationed on the platform. Just before the train was due to pull in it was learned that Balfour had gotten off the train in Al-Qadam station. The crowds subsequently rushed off to Victoria Hotel where guards prevented anyone from entering. Secret service agents had infiltrated the crowds, who chanted cries against the Balfour Declaration and the man's visit to the Ummayad capital and cheered for the long life of Palestine. The demonstration lasted for an hour, after which protesters made off to Hamidiya Market."

In the famous Damascus marketplace, hordes of people began to emerge from the streets and alleyways and began to converge on the Square of Martyrs.

"At this point, the police began to intervene, blocking passage over the Barada Bridge in the face of angry, noisy crowds. Violent clashes broke out between the people and police, who took those whom they captured to the police station."

Al-Ahram's correspondent then relates that at about 11:00 that evening, after the crowds dispersed, Lord Balfour decided he would take a walk in the city but was dissuaded by the urgent appeals of the French police authorities. "He thus returned to his room as police and security forces patrolled the city and the site around the hotel throughout the night."

|

|

The following day saw further unrest. After noon prayers, Al-Ahram's correspondent reports, crowds rushed towards Victoria Hotel, "crashed the police barricades and almost reached the doors of the hotel." The reporter continues, "The gendarmes tried to block them and were finally forced to fire shots in the air. At 2:00 pm, eight armoured vehicles were sent to restore order."

According to several news agencies, approximately 50 protesters were wounded, three in critical condition. Fifteen ended up in hospital. Two policemen were also injured while many suffered bruises and contusions. That no one was killed was undoubtedly due to the discipline and self-restraint of the French police who fired in the air despite the serious situation.

The following day, Al-Ahram's correspondent reports, aircraft flew over the city at an altitude of 150 metres while dozens of armoured vehicles and tanks were brought in. This time, protesters came up against French and Moroccan infantry and cavalry armed with swords. In the battle that ensued, most of the injuries among the demonstrators were sword wounds, while the injuries sustained by the French were inflicted by stones hurled by the protesters. During this fighting, Balfour made no attempt to leave his room. In his company were the correspondents from The London Times and The Daily Telegraph who dispatched to their newspapers detailed accounts of the clash that was taking place within earshot of the hotel.

Eventually, French forces moved into and occupied Al-Marja Al-Khadra and Martyrs' Square but French authorities knew this would be insufficient to restore calm to the Syrian capital. Thus, in a meeting with Lord Balfour and the British consul in Damascus, the French commanding general persuaded him to leave the city at once, having spent less than 24 hours in the historic Arab capital during which "he never once left his room."

In order to spirit the visiting British dignitary out of the city with the least disturbance possible, the French general devised a clever ploy. He stationed himself on a bridge near the hotel while airplanes swooped overhead, "thus distracting the people's attention." It was then that Balfour managed to leave the hotel without drawing attention, remarkable in view of the fact that his cortege was guarded by some 60 police and security officers. Simultaneously, government authorities in Damascus ordered sentinels to call all local elders to an assembly to instruct them to inform their various quarters in the city that Balfour had left.