|

October 1, 2016 - No. 38

Supplement

For Your

Information

Resistance at

Standing Rock

• Background

on Standing Rock

Struggle

• Excerpts from Standing Rock Sioux

Tribe Resolution

Opposing Dakota Access Pipeline

• Violations of Federal Law in

Pipeline Approval

• We Are Still Here. We Are Still

Fighting for Our Lives on Our Own Land

- LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Standing Rock Sioux -

• We Are Protectors, Defending the

Land And Water

- Iyuskin American Horse, Canyon Ball, North Dakota -

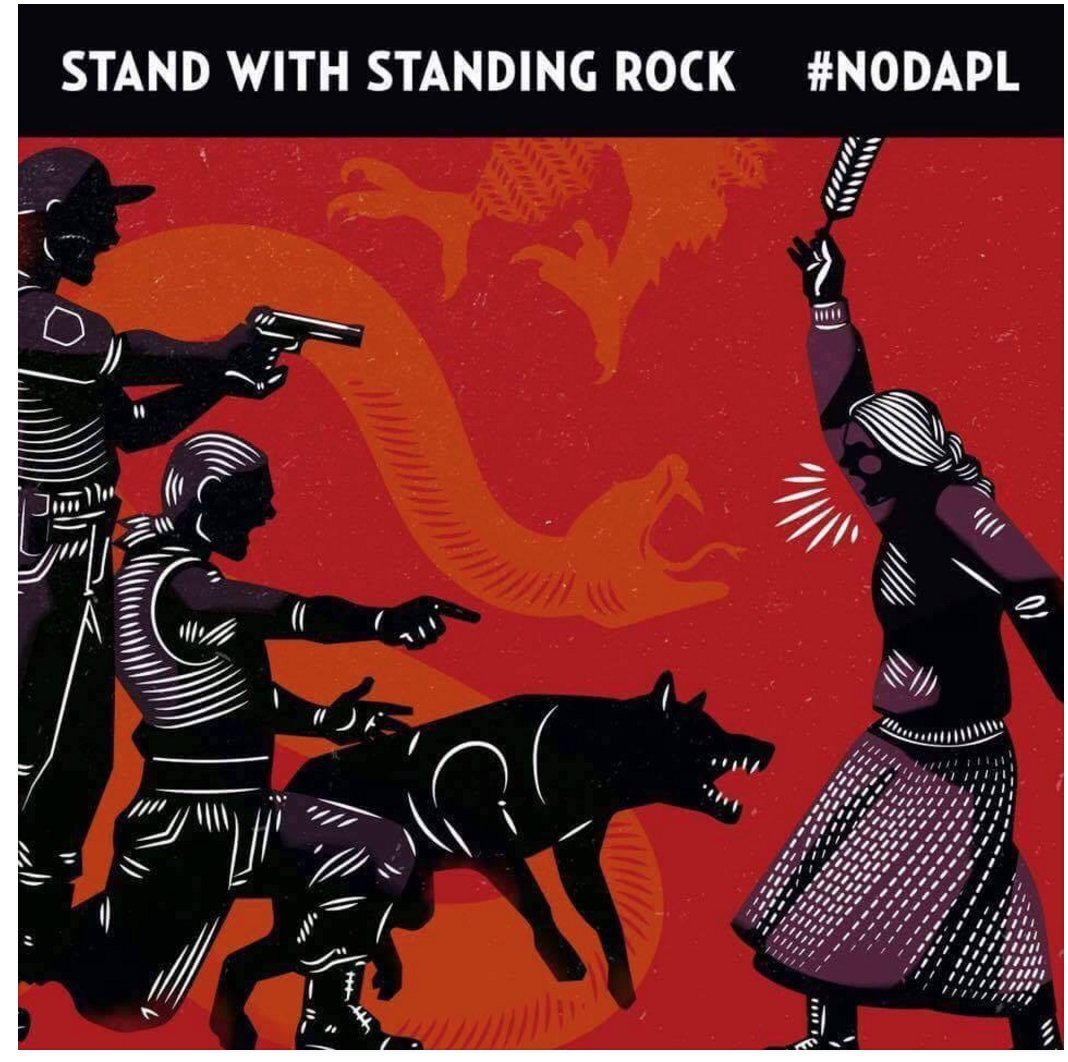

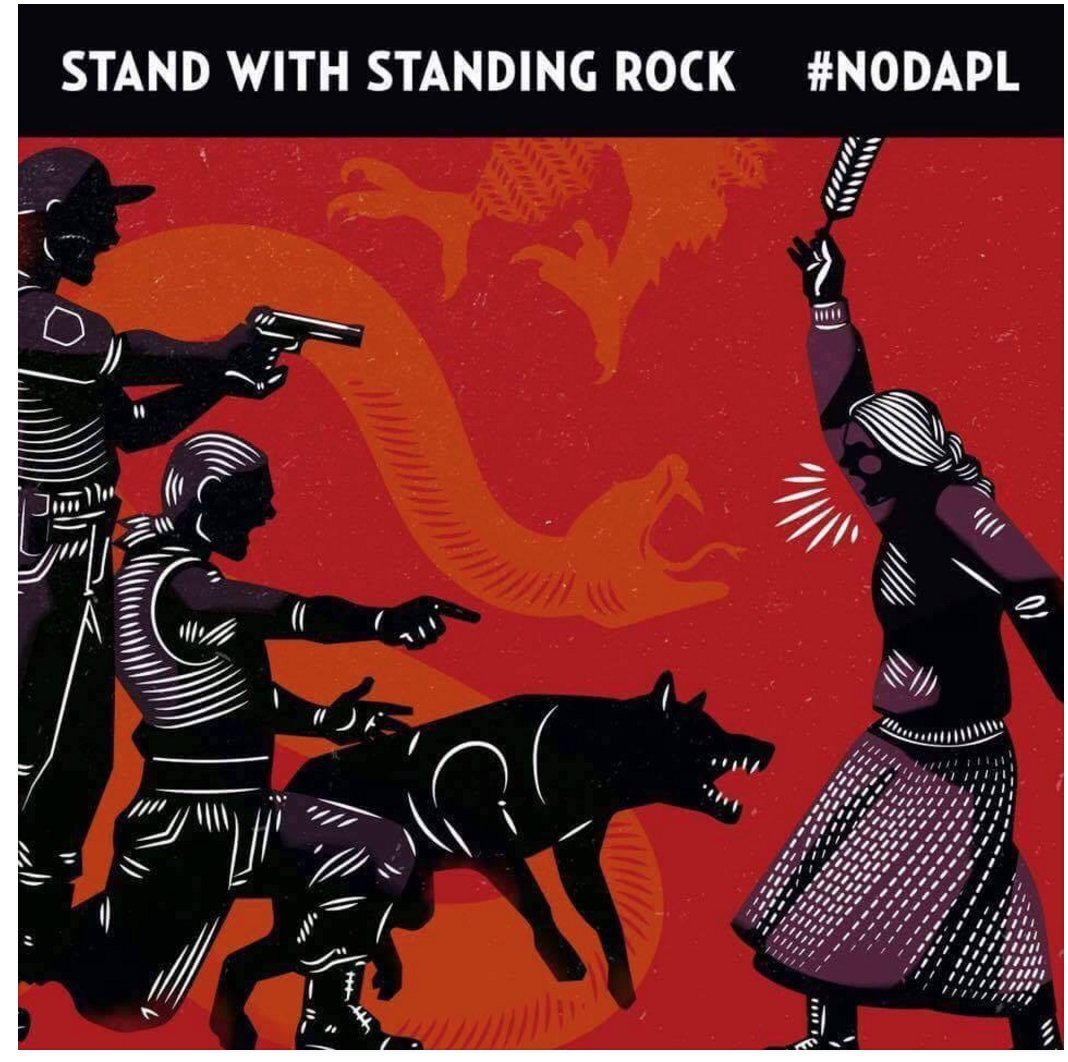

• The Vicious Dogs of Manifest

Destiny Resurface in North Dakota

- Jacqueline Keeler -

For Your

Information -- Resistance at Standing

Rock

Background on Standing Rock Struggle

April 2016

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal members began protesting the

1,885-kilometre, four state, Dakota Access Pipeline

construction by setting up the Sacred Stone Camp (sacredstonecamp.org) along the

banks of Lake Oahe in North Dakota. They are organizing to protect and

ensure safe water for millions, as the pipeline crosses both the

Missouri River and Lake Oahe. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has been

locked in a battle to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline from impacting

its cultural, water, and natural resources. The pipeline will transport

as much as 570,000 barrels of oil each day from North Dakota to

Illinois. The Army Corps of Engineers green-lighted several sections of

the process without fully satisfying the National Historic

Preservation Act, various environmental statutes, and its trust

responsibility to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

Camp meeting at Sacred Stones camp of Standing Rock Sioux.

This is another chapter in the long history of the U.S.

federal government granting the construction of potentially hazardous

projects near or through tribal lands, waters, and cultural places

without consulting the tribe. The current proposed pipeline route

crosses under Lake Oahe, just 800 metres up from the Standing Rock

Sioux Reservation. It is not a question of if the pipeline will leak,

but when. This is evident from recent oil spills, including the release

of more than 300,000 litres of oil near Tioga, North Dakota in October

2013; nearly 200,000 litres of oil released into the Yellowstone River

upstream from Glendive, Montana resulting in the shutdown of the

community water system for 6,000 residents in January 2015; and the

release of 3.79 million litres of tar sands crude into Michigan's

Kalamazoo River in July 2010.

August 2016

Standing Rock Sioux youth run from North Dakota to Washington DC.

Youth from the Standing Rock Sioux tribe run from their

tribal lands in North Dakota to Washington, DC to call for a halt to

the DAPL and respect for their treaty rights and for the water and

Mother Earth.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed suit in federal

district court in Washington, DC against the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers, which is the primary federal agency that granted the permits

needed for construction of the pipeline.

September 2016

The Sacred Stone Camp

supporters

grow by the thousands with 280 tribes represented. National attention

grows from the broad and increasing support among Indigenous peoples

and many others.

- The Dakota Access Pipeline guards, including

notorious G4S, known for their inhumane treatment of women and children

in detention centres and of Palestinian youth, unleash attack dogs on

American Indian water protectors, including women and children.

- North Dakota Governor activates the National Guard to

protect the pipeline instead of the indigenous peoples, including

checkpoints

with armed guardsman requiring all to stop. It was also reported

that members of Red Warrior camp have been arrested and that law

enforcement check points are photographing people, perhaps to

make mass arrests later. Activists are urged to avoid the check

points.

- September 9, Federal court denies the Standing Rock

Tribe's

request for an injunction. However, a joint statement from the

Department of Justice, the Department of the Army, and the

Department of the Interior asked for construction to voluntarily

be ceased on federally controlled lands.

- The Sacred Stone Camp remains strong and united,

preparing

to remain through the winter. Support and actions also continue

across the country, including demonstrations, gathering supplies

and funds, and making the journey to the camp to lend a hand.

Excerpts from Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Resolution

Opposing

Dakota Access Pipeline

WHEREAS, the Standing Rock Indian Reservation was

established as a permanent homeland for the Hunkpapa, Yanktonai,

Cuthead and Blackfoot bands of the Great Sioux Nation;

and

WHEREAS, the Dakota Access Pipeline threatens public

health

and welfare on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation; and

|

Edmonton, September 11, 2016.

|

WHEREAS, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe relies on the

waters

of the life-giving Missouri River for our continued existence,

and the Dakota Access Pipeline poses a serious risk to Mni Sose

and to the very survival of our Tribe; and

WHEREAS, the horizontal direction drilling in the

construction of the pipeline would destroy valuable cultural

resources of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe; and

WHEREAS, the Dakota Access Pipeline violates Article 2

of the

1868 Fort Laramie Treaty which guarantees that the Standing Rock

Sioux Tribe shall enjoy the "undisturbed use and occupation" of

our permanent homeland, the Standing Rock Indian Reservation;

NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED, that the Standing Rock

Sioux

Tribal Council hereby strongly opposes the Dakota Access

Pipeline; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the Standing Rock Sioux

Tribal

Council call upon the Army Corps of Engineers to reject the river

crossing permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline....

Violations of Federal Law in Pipeline Approval

The federal government, including the Department of

Justice and Army Corps of Engineers, gave the green light for

construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, from North Dakota to

Illinois, despite violations of federal law and treaty rights by

the energy monopolies involved. While currently there has been a

temporary halt to some sections of the pipeline -- as a result of

the firm stand of the Standing Rock Sioux and hundreds of other

tribes and organizations to protect the water and scared burial

grounds -- the government has not called for ending construction

of the pipeline.

Below are treaty rights and federal laws being violated.

Fort Laramie Treaty of April 29, 1868: The

Dakota

Access Pipeline violates Article 2 of the 1868 Fort

Laramie Treaty which guarantees that the Standing Rock Sioux

Tribe shall enjoy the "undisturbed use and occupation" of their

permanent homeland, the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The

U.S. Constitution states that treaties are the supreme law of the

land.

Executive Order 12898 on Environmental Justice:

All agencies must determine if the proposed project disproportionately

impacts Tribal communities or other minority communities. The Dakota

Access Pipeline was originally routed to cross the Missouri River north

of Bismarck. The crossing was moved to "avoid

populated areas," so instead of crossing upriver of the state's

capital, it crosses the aquifer of the Great Sioux

Reservation.

Pipeline Safety Act and Clean Water Act: Dakota

Access Pipeline has not publicly identified the Missouri River crossing

as high consequence, though it provides water for more than 17 million

people. The Ogallala Aquifer must also be considered a "high

consequence area," since the pipeline would cross critical drinking

water and intakes for those water systems. The emergency plan must

estimate the maximum possible spill (49 CFR§195.452(h)(iv)(i)).

Dakota Access Pipeline refuses to release this information to the Sioux.

National Environmental Policy Act: A detailed

Environmental Impact Statement must be completed for major actions that

affect the environment. Also, the Army Corps of Engineers must comply

with the National Environmental

Policy Act for the permit for the Missouri

River crossing. The way agencies get around this is to provide a lesser

study, a brief Environmental Assessment (which Dakota Access has done).

A full Environmental Impact Statement would be an interdisciplinary

approach with the integrated use of natural and social sciences to

determine direct and indirect effects of the project and "possible

conflicts... with Indian land use plans and policies... [and] cultural

resources" (40 CFR §1502.16).

Executive Order 13007 on Protection of Sacred Sites:

"In managing federal lands, each executive branch agency shall avoid

adversely affecting the physical integrity of such sites." There are

historical ceremony sites and burial grounds in the immediate vicinity

of the Missouri River crossing. The Corps must deny the Dakota Access

Pipeline permit to protect these sites in compliance with Executive

Order 13007.

We Are Still Here. We Are Still Fighting for

Our Lives on Our

Own Land

- LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, Standing

Rock

Sioux -

On the front lines of stopping the Dakota Access Pipeline, August, 2016. (D. Kane)

On this day, 153 years ago [September 3, 1863], my

great-great-grandmother

Nape Hote Win (Mary Big Moccasin) survived the bloodiest conflict

between the Sioux Nations and the U.S. Army ever on North Dakota

soil. An estimated 300 to 400 of our people were killed in the

Inyan Ska (Whitestone) Massacre, far more than at Wounded Knee.

But very few know the story.

As we struggle for our lives today against the Dakota

Access Pipeline, I remember her. We cannot forget our stories of

survival.

Just 50 miles [80 kilometres] east of here, in 1863,

nearly 4,000

Yanktonais,

Isanti (Santee), and Hunkpapa gathered alongside a lake in

southeastern North Dakota, near present-day Ellendale, for an

intertribal buffalo hunt to prepare for winter. It was a time of

celebration and ceremony -- a time to pray for the coming year,

meet relatives, arrange marriages, and make plans for winter

camps. Many refugees from the 1862 uprising in Minnesota, mostly

women and children, had been taken in as family. Mary's father,

Oyate Tawa, was one of the 38 Dah'kotah hanged in Mankato,

Minesota, less than a year earlier, in the largest mass execution

in the country's history. Brigadier General Alfred Sully and

soldiers came to Dakota Territory looking for the Santee who had

fled the uprising. This was part of a broader U.S. military

expedition to promote white settlement in the eastern Dakotas and

protect access to the Montana gold fields via the Missouri

River.

As my great-great-grandmother Mary Big Moccasin told

the

story, the attack came the day after the big hunt, when spirits

were high. The sun was setting and everyone was sharing an

evening meal when Sully's soldiers surrounded the camp on

Whitestone Hill. In the chaos that ensued, people tied their

children to their horses and dogs and fled. Mary was 9 years old.

As she ran, she was shot in the hip and went down. She laid there

until morning, when a soldier found her. As he loaded her into a

wagon, she heard her relatives moaning and crying on the

battlefield. She was taken to a prisoner of war camp in Crow

Creek where she stayed until her release in 1870.

Where the Cannonball River joins the Missouri River, at

the

site of our camp today to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, there

used to be a whirlpool that created large, spherical sandstone

formations. The river's true name is Inyan Wakangapi Wakpa, River

that Makes the Sacred Stones, and we have named the site of our

resistance on my family's land the Sacred Stone Camp. The stones

are not created anymore, ever since the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers dredged the mouth of the Cannonball River and flooded

the area in the late 1950s as they finished the Oahe dam. They

killed a portion of our sacred river.

I was a young girl when the floods came and desecrated

our

burial sites and Sundance grounds. Our people are in that

water.

This river holds the story of my entire life.

I remember hauling our water from it in big milk jugs

on our

horses. I remember the excitement each time my uncle would wrap

his body in cloth and climb the trees on the river's banks to

pull out a honeycomb for the family -- our only source of sugar. Now

the river water is no longer safe to drink. What kind of world do

we live in?

Look north and east now, toward the construction sites

where

they plan to drill under the Missouri River any day now, and you

can see the old Sundance grounds, burial grounds, and Arikara

village sites that the pipeline would destroy. Below the cliffs

you can see the remnants of the place that made our sacred

stones.

Of the 380 archeological sites that face desecration

along

the entire pipeline route, from North Dakota to Illinois, 26 of

them are right here at the confluence of these two rivers. It is

a historic trading ground, a place held sacred not only by the

Sioux Nations, but also the Arikara, the Mandan, and the Northern

Cheyenne.

Again, it is the U.S. Army Corps that is allowing these

sites

to be destroyed.

The U.S. government is wiping out our most important

cultural

and spiritual areas. And as it erases our footprint from the

world, it erases us as a people. These sites must be protected,

or our world will end, it is that simple. Our young people have a

right to know who they are. They have a right to language, to

culture, to tradition. The way they learn these things is through

connection to our lands and our history.

If we allow an oil company to dig through and destroy

our

histories, our ancestors, our hearts and souls as a people, is

that not genocide?

Today, on this same sacred land, over 100 tribes have

come

together to stand in prayer and solidarity in defiance of the

black snake. And more keep coming. This is the first gathering of

the Océti Sakówin (Sioux tribes) since the Battle of the

Greasy

Grass (Battle of Little Bighorn) 140 years ago. When we first

established the Sacred Stone Camp on April 1 to stop the pipeline

through prayer and non-violent direct action, I did not know what

would happen. But our prayers were answered.

We must remember we are part of a larger story. We are

still

here. We are still fighting for our lives, 153 years after my

great-great-grandmother Mary watched as our people were

senselessly murdered. We should not have to fight so hard to

survive on our own lands.

My father is buried at the top of the hill, overlooking

our

camp on the riverbank below. My son is buried there, too. Two

years ago, when Dakota Access first came, I looked at the

pipeline map and knew that my entire world was in danger. If we

allow this pipeline, we will lose everything.

We are the river, and the river is us. We have no

choice but

to stand up.

Today, we honor all those who died or lost loved ones

in the

massacre on Whitestone Hill. Today, we honor all those who have

survived centuries of struggle. Today, we stand together in

prayer to demand a future for our people.

We Are Protectors, Defending the Land And Water

- Iyuskin American Horse, Canyon Ball,

North

Dakota -

Our elders have told us that if the zuzeca sape, the

black

snake, comes across our land, our world will end. Zuzeca has come -- in

the form of the Dakota Access Pipeline -- and so I must

fight.

I am Sicangu/Oglala Lakota,

born in Rosebud, South

Dakota,

and writing from the frontline of the movement against the

pipeline in Cannon Ball. I have been holding this ground with my

Standing Rock Sioux tribe relatives since the spring. I am

defending the land and water of my people, as my ancestors did

before me. I am Sicangu/Oglala Lakota,

born in Rosebud, South

Dakota,

and writing from the frontline of the movement against the

pipeline in Cannon Ball. I have been holding this ground with my

Standing Rock Sioux tribe relatives since the spring. I am

defending the land and water of my people, as my ancestors did

before me.

The $3.8bn pipeline project is proposed to carry

approximately 470,000 barrels per day of fracked oil from our

Bakken oil fields, 1,172 miles [1,885 kilometres] through the country's

heartland,

to Illinois. The pipeline will cross the confluence of the

Cannonball and Missouri rivers, where it threatens to contaminate

our primary source of drinking water and damage the bordering

Indigenous burial grounds, historic villages and sundance sites

that surround the area in all directions. Those sites that were

not desecrated when the area was flooded in 1948 by the

construction of the Oahe dam are now in danger again.

I have seen where their machines clawed through the

earth

that once held my relatives' villages.

This week, I have witnessed pipeline construction tear

its

way toward the waters of the Missouri river which flow into the

Mississippi, threatening to pollute the aquifer that carries

drinking water to 10 million people. I have seen where their

machines clawed through the earth that once held my relatives'

villages. I have watched law enforcement officials protect the

oil industry by dragging away my Indigenous brothers and sisters

who stood up for our people.

The fact that Energy Transfer Partners, the company

behind

the pipeline, would use the word "Dakota," which means "friend"

or "ally," in the name of its project is disrespectful. This

pipeline is a direct threat to all Dakota, Lakota and Nakota

people, especially our future generations. And we are not the

only ones. We know that burning this oil is changing our climate

and Indigenous people all over the world are bearing the brunt of

the catastrophes that causes.

This pipeline poses threats strikingly similar to those

posed

by the now defeated Keystone XL, but has received a fraction of

the attention from mainstream media and big environmental groups.

On July 26, we were surprised to learn that the North Dakota

permits were approved by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to run

the pipeline within a half-mile of our reservation. My tribal

leaders have said that this was done without consulting tribal

governments, and without a meaningful study of the impacts it

will have. This is a violation of federal law and, more

importantly, of our treaties with the U.S. government -- the supreme

law of the land.

It was my Ina, my mother, who first told me of this

struggle.

With my Ina, ciye (older brother), and tunwin (aunt) we have

joined our Standing Rock relatives to face this new storm. For

the past month, we have stood with Standing Rock in solidarity,

we have prayed, we have cried, and we have also laughed, even

when we thought it impossible to do so.

I never thought I would be on the frontline of a fight

like

this. I grew up admiring Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and my

ancestor American Horse, for their courage and leadership in

battle against their oppressors. Now I am fighting alongside

their descendants, my relatives from all seven tribes, against

the very same oppressors.

It saddens me that the government time and time again

continues to ravage my people with the same treatment and

attitude, only different weapons. But why should [we] be surprised?

This is the definition of insanity -- to go through the same

situations over and over believing the outcome will be

different.

This camp was created as a last defense for the water

that

our communities depend on to survive. I have watched our numbers

dwindle down to the single digits, and now we have swelled to

over 300 people in just a few days. Hundreds more are on the way

right now, as other tribes gather resources to send people and

supplies.

This historic battle is bringing the Océti

Sakówin

together

like nothing has ever before. The Hunkpapa, the tribal band of

Standing Rock, are now joined by the Oglala from Pine Ridge, the

Sicangu from Rosebud, and relatives from Crow Creek, Cheyenne

River, and Yankton, as well as Dine and Ponca relatives from the

south, Ojibwe relatives from the Great Lakes, and countless

others. From all across the country, tribes are bringing us

shelter, food and most importantly, prayers.

To have all this unity of tribes standing together in

solidarity before my eyes is a beautiful sight. Our tribes now

live together, eat together, and pray together on the front

lines.

We are not protesters. We are protectors. We are

peacefully

defending our land and our ways of life. We are standing together

in prayer, and fighting for what is right. We are making history

here. We invite you to stand with us in defiance of the black

snake.

The Vicious Dogs of Manifest Destiny

Resurface in North

Dakota

- Jacqueline Keeler -

Private corporate mercenaries hired by Energy Transfer

Partners sicced attack dogs upon a crowd of Native Americans and

their allies, including children, on September 3 who were

nonviolently trying to stop the desecration of sacred burial

grounds and culturally significant archaeological sites by the

company constructing the Dakota Access Pipeline. Six people were

bitten, including one child and a pregnant woman, while 30 were

also maced by the security team.

The gathering of water

protectors was estimated at 300,

assembled after the pipeline construction crew abruptly moved

three bulldozers to a site nearly 15 miles [24 kilometres] away -- a

site

identified the day before by Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's historic

preservation officer as containing important cultural and historical

sites. The gathering of water

protectors was estimated at 300,

assembled after the pipeline construction crew abruptly moved

three bulldozers to a site nearly 15 miles [24 kilometres] away -- a

site

identified the day before by Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's historic

preservation officer as containing important cultural and historical

sites.

Native American human remains were most likely

disturbed by

Dakota pipeline workers -- a federal crime. The site is on private

land and the Tribe had received permission from the landowner to

inspect the area adjacent to the pipeline corridor. Texas-based

Energy Transfer Partners, in an apparent attempt to avoid a legal

challenge, may have acted preemptively to destroy the historic

value of the site before a judge could rule on the evidence.

It was a brutal and vicious act.

The land, adjacent to the reservation's northern

border, is

within the treaty territory of the Tribe under the 1868 Treaty of

Fort Laramie and the Tribe retains legal claims to historical

sites there.

"They wanted to destroy the proof and evidence; the

company

knew those sites were there," Standing Rock Sioux Tribal chairman

Dave Archambault told the Bismarck

Tribune. "They don't normally

work on Saturday and Sunday; we know because we've been watching

them. They desecrated all the land where the landowner gave us

permission to look."

In response, the Obama administration took immediate

action

on Labor Day and issued a temporary restraining order against

Dakota Access Pipeline construction, noting concerns about the

oil company "engaging with or antagonizing" the #NoDAPL resistors

warranted a restraining order. This is the first comment of any

kind on the situation given by the administration and President

Barack Obama has been notably silent on this matter, despite the

protest going on since April 1.

In 2014, Obama visited the very site of the

encampment,

Cannonball, North Dakota and promised the Standing Rock Sioux

Tribe he would be a president who "respects your sovereignty, and

upholds treaty obligations, and who works with you in a spirit of

true partnership, in mutual respect, to give our children the

future that they deserve."

Many have called upon Obama

to honor these promises via

social media and even tribal council resolutions, and apparently

the video and photos of private security dogs with peaceful

protesters' blood in their mouths finally spurred the

administration to some action. Many have called upon Obama

to honor these promises via

social media and even tribal council resolutions, and apparently

the video and photos of private security dogs with peaceful

protesters' blood in their mouths finally spurred the

administration to some action.

And what does it mean when the state or state-backed

corporate conquistadors use dogs and violence to suppress the

will of the people peacefully expressed? For many, the brutality

of Energy Trust Partner's hired security forces, with law

enforcement's tacit support and given favorable coverage by the

mainstream media, is a sign that this pipeline is yet another

example of the forced occupation of Océti Sakówin (the

Great

Sioux Nation) lands.

"Dakota is our name -- it means allies, friends," Faith

Spotted

Eagle, Ihanktonwan elder and founder of the Brave Heart Society

who has been camping at the Océti Sakówin camp at

Cannonball to

oppose the pipeline told TeleSUR. "How can they use it for their

pipeline? They are not being allies to us or to our Mother

Earth."

The malicious use of dogs on the people, the allies,

the true

Dakota, simply underscores the impunity of the corporate power to

use other peoples' lands as they see fit with little or no regard

for the well-being of people or nations.

The use of violence in the service of American

domination has

a bloody and well-remembered history among the Dakota/Lakota

people of the Great Plains and Minnesota. In 1863, the Dakota

rose up as their treaty provisions were denied and their children

were starving in what is called the Minnesota Sioux Uprising.

They were quickly put down and 4,000 fled to join their relatives

among the Dakota and Lakota and Nakota bands in the Dakotas and

in Canada. Thirty-eight Dakota men were hung by President Lincoln

in the largest mass hanging in U.S. history in Mankato,

Minnesota.

And this latest assault with dogs by an oil company on

Océti

Sakówin and their allies takes place exactly 153 years to the

day

since the Whitestone Massacre which occurred on September 3, 1863

not far from the present day protest at Cannonball, North

Dakota.

In an article for Yes! Magazine, Brave Bull

Allard

recalls what her great-great grandmother, Mary Big Moccasin, a

Santee survivor of that violent attack (Big Moccasin's father was

one of the 38 hung at Mankato) remembered about that day:

"The attack came the day after the big hunt, when

spirits

were high. The sun was setting and everyone was sharing an

evening meal when (Colonel) Sully's soldiers surrounded the camp

on Whitestone Hill. In the chaos that ensued, people tied their

children to their horses and dogs and fled. Mary was 9 years old.

As she ran, she was shot in the hip and went down. She laid there

until morning, when a soldier found her. As he loaded her into a

wagon, she heard her relatives moaning and crying on the

battlefield. She was taken to a prisoner of war camp."

This history of violence begs the question, what was

Manifest

Destiny? What was the United States of America built on? Is it

this genocide and impunity, this belief that everything here,

everything belonging to the nations of people that already were

here, even their very lives, are free for the taking? Has

everyone who came to America come here to partake in this

barbarism?

I compare this to the terms my Dakota ancestors used to

describe themselves. Dakota, allies/friends versus Dakota

Access -- which clearly means access to everything that belongs to

us, a latter-day Manifest Destiny, a latter-day expression of

this genocidal impunity. And to another term, Ikce Wicasa,

variously interpreted as "free" and "humble people." It may seem

odd that a people known around the world by the exploits of

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse would think of themselves in those

terms -- indeed regard those terms as the highest terms of humanity

that could be expressed. For them, to be humble was to be truly

free. To be allied with each other to preserve the lives, their

relationship to the each other and to the Earth was what it meant

to be human.

I can't help but compare Ikce Wicasa to the term

"Pioneer"

which is derived from the French term for peons, lower class

folks who were considered expendable and sent ahead of the

regular army as cannon fodder. And I remember the story recorded

by my great-great aunt Ella Deloria, a Yankton Dakota ethnologist

from elders she interviewed 100 years ago, of how the railroad

once dumped white people off in North Dakota with nothing but a

box to live in. They were left along railroad lines to act as a

buffer between the railroad and the "Indians." Ironically, it was

our people that often had to come to their aid because they were

basically left to starve by those railroad tycoons.

There was a term in our language my Lala (grandfather)

once

told me that meant "that which looks human but is not" and when I

look at a photo taken of Energy Transfer Partner's CEO Kelcy

Warren watching a #NoDAPL protest outside his Texas corporate

offices on Friday [September 2] smirking the day before he ordered dogs

to bite

Native Americans and even children and pregnant women, I can't

help but wish I remembered what that word was.

Because that is what he is.

Jacqueline Keeler is a Navajo/Yankton Dakota Sioux

writer

living in Portland, Oregon. She has been published in Salon,

Indian Country Today, Earth Island Journal and the Nation. She is

finishing her first novel "Leaving the Glittering World" set in

the shadow of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington State

during the discovery of Kennewick Man.

PREVIOUS

ISSUES | HOME

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|

I am Sicangu/Oglala Lakota,

born in Rosebud, South

Dakota,

and writing from the frontline of the movement against the

pipeline in Cannon Ball. I have been holding this ground with my

Standing Rock Sioux tribe relatives since the spring. I am

defending the land and water of my people, as my ancestors did

before me.

I am Sicangu/Oglala Lakota,

born in Rosebud, South

Dakota,

and writing from the frontline of the movement against the

pipeline in Cannon Ball. I have been holding this ground with my

Standing Rock Sioux tribe relatives since the spring. I am

defending the land and water of my people, as my ancestors did

before me. The gathering of water

protectors was estimated at 300,

assembled after the pipeline construction crew abruptly moved

three bulldozers to a site nearly 15 miles [24 kilometres] away -- a

site

identified the day before by Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's historic

preservation officer as containing important cultural and historical

sites.

The gathering of water

protectors was estimated at 300,

assembled after the pipeline construction crew abruptly moved

three bulldozers to a site nearly 15 miles [24 kilometres] away -- a

site

identified the day before by Standing Rock Sioux Tribe's historic

preservation officer as containing important cultural and historical

sites. Many have called upon Obama

to honor these promises via

social media and even tribal council resolutions, and apparently

the video and photos of private security dogs with peaceful

protesters' blood in their mouths finally spurred the

administration to some action.

Many have called upon Obama

to honor these promises via

social media and even tribal council resolutions, and apparently

the video and photos of private security dogs with peaceful

protesters' blood in their mouths finally spurred the

administration to some action.