|

June 6, 2015 - No. 23 Supplement Anglo-American Nazi Appeasement,

Conciliation

and Anti-Communism

|

Proposed itinerary for Mackenzie King's June 1937 visit to Berlin. Click to enlarge. |

Göring said they understood perfectly the feeling of unity of the British Empire, and asked whether we would necessarily follow Britain in everything. I told him that was to misunderstand altogether our real position. We were just as free a country as any other. We made our own decisions in the light of questions raised. He then said, as an example, I would like to put a direct question: If the peoples of Germany and Austria, being of the same race, should wish to unite at any time, if Britain were to try to prevent them, would Canada back up Britain in any action of the kind? I said: our attitude in this matter would be the same as for all other possible questions which might arise, we would wish to examine all the circumstances surrounding the matter, and would take our decisions in the light of the facts as existing at the time, and all the circumstances considered. General Göring said he thought that was a very reasonable attitude. I said it was simply the position I had stated in Parliament, and which was known to be the Canadian position irrespective of the country to which they related.

General Göring then said: Because I have put the question in this way, I do not wish you to think that there is going to be any attempt to take possession of Austria, but I am speaking of a development which might come in time. He also spoke of the cramped position of Germany, and the necessity of her having opportunity for expansion in Europe. He then said he could not understand why England should have been so annoyed or surprised at von Neurath canceling his trip to England at the time of the Leipzig incident. He said they would surely see in England that the Foreign Secretary would be needed at home at the time of any crisis arising. Herr Hitler particularly wanted his Foreign Minister when he was dealing with such a question. I said to him that I thought any expression arose from disappointment; they had been looking forward to the visit of von Neurath, also that the English people having their worldwide interests, were inclined not to attach the same importance to incidents as other countries might. That they would not like to show to the world that they were, in any way, concerned about events; that was part of their general attitude.

England Trying to Control Germany's Actions

I told General

Göring that this was my third Conference, and that I never knew

the attitude

toward Germany to be as friendly as it was this year. When he said

something

about England trying to control Germany's actions, I told him what I

thought

England was most concerned about, was danger of some quick, precipitate

action being taken in any place, which might set the whole Europe

aflame; that

she was an interested observer in all matters of international concern.

I then

spoke to him about Chamberlain, and said that I had been greatly

pleased with

Chamberlain's understanding and attitude generally. It was fortunate

for a

number of us from Canada that we had come to know Chamberlain as well

as

we had. I was glad that we had come to see his real attitude; his

speech

the

other day in the House was just along the line he took in the

Conference.

Germany had many problems which had to be understood; that she was

showing restraint in dealing with some of them; also that it was not

for any

country to interfere in the particular policies of other countries.

Göring said he

was pleased to hear what I had said about Chamberlain.

I also said that I thought the present King was

understanding in his attitude; that he had spoken to me of Sir Neville

Henderson, and my finding him well suited for the post. (In this

connection, Herr Hewel had said to me they were afraid the present King

would not be as friendly toward Germany as King Edward; that the latter

had given the order to the war veterans to pay a visit to Germany). In

talking of the Empire, I said to him I was all for peace myself;

disliked very much spending money for war but at the last Session of

the Canadian Parliament, I had had to ask for increases for defence

simply because of general fear that has been engendered, that another

great war might come about through the re-arming going on. I said he

had to judge from this himself as to how Canada felt about the

preservation of the freedom she enjoyed within the British

Commonwealth; that I could not have held my Party together or true to

Canadian sentiment unless this step had been taken, that it was taken

wholly voluntarily, and irrespective of any representations from

Britain, and, as he knew, before the Imperial Conference.

I said I wished he might pay Canada a visit. He thanked

me quite cordially

and said that I was the first one to extend an invitation of the kind.

He spoke

about being very busy, but I said: busy men need a change and a trip

across

the ocean would be very pleasant. He said he would like to go some time

for

a few days' shooting of big game, elk or bear. I told him we would be

glad

to see necessary arrangements were made.

The interview with Göring lasted from 10.30 till 12. It was quite clear the General had many other engagements which he was letting slip by. There was just time to come to the Hotel to call on Herr Hitler at 12.45.

Interview with Adolf Hitler

When we reached old Hindenburg Palace, we were greeted by a guard of honour. The entire building is like an old palace, and the attendants were attired in court dress. We were shown in what had been Hindenburg's office, and shown the death mask which reposes on his desk and his portrait on the wall.

Later we were conducted upstairs, preceded formally by attendants. We had been previously met by members of the Foreign Office and Hitler's staff. When I was formally shown into the room in which Herr Hitler received me, he was facing the door as I went in; was wearing evening dress; came forward and shook hands; quietly and pleasantly said he was pleased to see me in Germany, and pointed to a seat which was in front of a small table which had a chair to its back, to the right of which Herr Hitler seated himself. Mr. Schmidt sat to Hitler's left. When I went in, there were some other persons present as well. It was explained to me afterwards that Hitler had been receiving some foreign diplomats presenting letters which accounted for other officials being present at the time. One of these was in military uniform; others in Court dress. We had just gotten under was in conversation when Pickering and Hewel came in. I counted altogether eleven in the room hearing our conversation. The interview lasted until after two; one and a quarter hours altogether.

As we were about to be seated, I placed a de luxe copy of Rogers' biography on the table, and opened it at the pictures of the cottage where I was born, and of Woodside, of Berlin. I told Herr Hitler that I had brought this book with me to show him where I was born, and the associations which I had with Berlin, Germany, through Berlin, Canada. That I would like him to know that I had spent the early part of my life in Berlin, and had later represented the county of Waterloo in Parliament with its different towns which I named over. I said I thought I understood the German people very well. I mentioned that I had also been registered at the municipality of Berlin 37 years ago, and had lived with Anton Weber at the other side of the Tiergarten. While I was speaking, Hitler looked at the book in a very friendly way, and smiling at me as he turned over its pages and looked at its inscription. He thanked me for it, and then waited for me to proceed with conversation.

Arming Made Necessary to Maintain Respect,

a Consequence of the

Treaty of Versailles

I told him I had been anxious to visit Germany because of these old associations, and also because I was most anxious to see the friendliest of relations existing between the peoples of the different countries. I had meant to pay the visit last year but had not had the chance. I was particularly grateful to von Ribbentrop for his kindness in arranging such an interesting programme. I said I had been particularly anxious to meet Herr Hitler himself and talk over matters of mutual interest.

I spoke then of what I had seen of the constructive work of his regime, and said that I hoped that that work might continue. That nothing would be permitted to destroy that work. That it was bound to be followed in other countries to the great advantage of mankind. Hitler spoke very modestly in reference to it, saying that Germany did not claim any proprietorship in what had been undertaken. They had accepted ideas regardless of the source from which they came, and sought to apply them if they were right. He cited, as an example, having obtained from "Roumania", I think, one of the ideas regarding improvement of labour's position, and had sought to apply it on a nationwide scale; that to make their views prevail, they had had to adopt [a form] of organization which would make the principles and policies prevail over the entire country; had had to go through a difficult time to reach that position but were now working out on those lines.

I said to him I hoped it would be possible to get rid of the fear which was making nations suspicious of each other, and responsible for increases of armaments. That could only do harm in the end. That I was a man who hated expenditures for military purposes; that the Liberal Government in Canada all shared my views in that particular; that I had the largest majority a Prime Minister had had in Canada. I had found it necessary, however, in order to keep my party united, and to meet the sentiment of the country to bring in increased estimates for expenditures on army, navy, and air services, at the last Session of Parliament. That this was due wholly to the fear that there might be another Great War, which fear had arisen from the way in which Germany was arming, etc. Hitler nodded his head as much as to say that he understood.

He then went on to say that in Germany, they had had to do some thing which they, themselves, did not like. That, after the War, they had been completely disarmed and had not sought to increase their armaments. On the other hand, France had not kept down the armaments but began to increase them at a rapid rate; Germany saw that if she was not to be at the mercy of conditions, she would have to take steps to enable her to defend herself. He said you must remember we were stripped of pretty nearly everything after the War, our colonies were taken away; we had no money to buy things with from outside. We had to do everything within the country itself; that meant that we had to organise so as to be able to get the defence equipment we needed. We had, in order to meet the situation, to arm much more rapidly than other nations would, or we would have armed had we been left in the position they were in after the war. Our purpose in arming is to get ourselves in the position where we will be respected. England has been arming rapidly, and we do not take any exception to it. We know that it is needed to give her voice the authority which it has. We feel the necessity of getting ourselves equally into the position where we would be respected. We have had once or twice to decide on certain moves which was a choice which we did not ourselves really like. We saw that we were either to be kept down and become permanently a subject depot, or take a step which would preserve us in our own rights. All our difficulties grew out of the enmity of the Treaty of Versailles, being held to the terms of that Treaty indefinitely made it necessary for us to do what we had done. He spoke of the advance into the Ruhr as being part of that assertion of Germany's position to save perpetual subjugation. He went on to say, however, that now most of the Treaty of Versailles was out of the way, moves of the kind would not be necessary any further.

Germany Has No Desire for War, War Would Obliterate European Civilization

He went on to say so far as war is concerned, you need have no fear of war, at the instance of Germany. We have no desire for war; our people don't want war, and we don't want war. Remember that I, myself, have been through a war, and all the members of the Government. We know what a terrible thing war is, and not one of us want to see another war, but let me go further. Let us assume that a war came, what would it mean? Assuming that France were to get the victory of a war against Germany, at what price would she have bought that victory? She would find her own country depopulated and destroyed as well as Germany. What she would find would be that European civilization had been wiped out.

But suppose we were to win in the war. What would we find? We would find exactly the same thing. We would have obliterated civilization of both countries, indeed of greater part of Europe; all that would be left, would be anarchy. What we should all do is to seek to circumscribe the area of any possible conflict. The Great War die not start in Germany. It started in ---. It spread to other parts of Europe, and became a world war. What should have been done was to have left the people who began fighting in the Balkans, continue to fight among themselves, and prevent the war from spreading. While he was speaking to the possibility of war, he said something to the effect that there were legitimate aspirations which a nation like Germany, in her position, should have, and be permitted to develop. That if they were not permitted to develop them in a natural way, then there might be trouble arising from Germany being prevented doing the things which were necessary to her existence but which could be done without any embarrassment to others. He did not see why Germany should not have the same rights as other nations in that regard.

Control Exercised by England, France, the League of Nations

He made some reference to the control that England, he thought, tried to exercise over Germany along with other countries. I said to him that I did not think England was trying to exercise control; I thought the position of England towards European matters could best be described as that of an interested observer; that what England was afraid of, was some precipitate step, action, being taken in some parts of Europe which would provoke conflict, which conflict might spread over the whole of Europe, and result in England herself and possibly the world being drawn into another Great World war. That I thought what England was most anxious for was that every care should be taken that progress was along evolutionary lines and no sudden steps might be taken which might have fatal consequences. Again Hitler said he understood that; that that was quite understandable, and that he, himself, and the German people felt the same way about the danger of precipitate steps. That he thought questions of that kind should be watched very closely.

It was at this point that he said that was the great danger of the League of Nations, that it tended to make a world war out of anything which should be a local affair. I said to him that I thought the Germans did not some times understand the English, or the English the Germans. I thought some of us in Canada understood both of them better than they did themselves. That we had exactly the same kind of feeling with regard to the English and the Americans; that in Canada we were continuously explaining to the English what the Americans really meant, in certain things, and to the Americans, what the English really meant; that it did not do to judge an Englishman too much by his head, they must look at his heart. They will find the heart all right and in the right place. I said, for example, that I had been talking with General Göring who had told me that the Germans could not understand why England should be annoyed at the Foreign Minister, Herr von Neurath, not continuing his trip to England. I said the Englishmen could not understand why the Germans would wish to discontinue the trip; that to understand the English attitude, they must have regard for the way England managed her affairs in the face of the world. That she was part of a great Empire that extended over many parts of the globe. That it would never do for her to show concern or alarm at any small incident. Rather she would wish to have the world feel that it was a matter of little or no real concern to her.

I said I had told Göring that if an Englishman happened to meet some people on his grounds when his own house was burning down, if he were in evening dress, he would begin to arrange his tie and see that his coat was in the right position, and would show as little in the way of concern as he possibly could, though he might be very anxious at heart; that Englishmen always sought to conceal their feelings or rather not to show them; that this would explain their attitude towards wondering why the Germans should have canceled von Neurath's trip. Had the situation been reversed, England would certainly have seen that the Foreign Minister continued his trip as if nothing had happened. Herr Hitler again nodded his head and looked at me, and then began talking to the interpreter, and said that the Leipzig affair was a serious one, and that he naturally wanted to have his Foreign Minister close at his hand at the time. That in reference to what I had said about von Neurath's trip still being continued, he would say there were two kinds of interviews -- one an interview such as he and I were having at the time which was a free and frank exchange of views, simply that each might come to understand the point of view of the other; that was all to the good, and was what had been intended by the visit of von Neurath to England. On the other hand, there were interviews and visits arranged which had a different purpose and which was to try and settle finally and definitely some concrete problems. Hitler then went on to say there are some problems which it is no use discussing at all, or trying to cause one party to change its mind on. He said, for example, I might try to persuade you that Canada should leave the British Isles, and that it was in your interest to do so. I could go on talking for weeks and for years but I know that it was no use, that you would not listen to what I said, no matter how effective the argument might be.

The Possibility of War, False Expectations Raised by the Press

He then said the same thing was true about trying to persuade Germany that she should enter into some agreement which would cause her country to go to war at some time in the future, under circumstances of which he had no knowledge at the present time, which it was impossible to foresee, that Germany would never bind herself to a commitment of that kind. That he, Hitler, in order to keep his control over the country had to have the support of the people; that he was not like Stalin who could shoot his Generals and other members of his Government who disagreed with him but had to have back of him what the people themselves really wished and the German people did not want war or commitments to possible war in advance. (While he was talking in this way, I confess I felt he was using exactly the same argument as I had used in the Canadian Parliament last Session).

He went on to say that the newspapers made no end of trouble; that before the time came for von Neurath to leave Germany, after his visit had been announced, the "Times" and the "Telegraph" and other papers had begun to set out all the things that were to be determined as a result of interview. They mentioned one subject after another which would be discussed and for which they hoped a settlement would be made. Hitler then said: some times, as a result of the Press, hopes are raised with regard to settlement of issues which never should have been raised at all, and to have the issues discussed and not settled, only makes the disappointment greater in the end than it would otherwise be. It was possible the lesser of two evils would be not to have an interview at all.

Question of the German Colonies, Dangers of Bolshevism and Communism

I told him I did not think the English had specific matters in mind, that really they were disappointed as they had been looking forward with great expectancy to the visit. A little later on, he spoke about the settlement of difficulties between England and Germany and France. He said he did not think there should be any difficulty in getting a complete understanding; that the question of the Colonies was one that they thought should not present difficulty; it could be settled in time. Now that the Treaty of Versailles was out of the way, the worse difficulties had gone with it. That he felt so far as France was concerned, they could easily reach an understanding which England, France, and Germany would all fully appreciate. The one thing, however, which he could not understand and which was presenting real difficulties was the Treaty of Alliance between France and Russia, and some other treaties that England had given her sanctions to.

I did not get a chance to answer this part of his statement as we had been talking a long time when it was reached. However, earlier, while discussing this matter, he spoke about the dangers of Bolshevism and Communism. He said England did not realize yet how serious they were, and what she might herself have to face some years hence. He said that if Germany had not met the Communist menace at the time she did, and in the way she did, the condition of Germany today would be the same as the conditions of Spain. That their whole life was being undermined by what was coming from Russia. (While talking with Göring, he said to me that they were surprised at the money which was going from England to help the Communists. He said they had knowledge of it; did not think the Government was a party to it but that some way or other, it got across from England to Spain.)

In speaking about the Conference in England, I told him that I had been at the Conference of 1923, and 1926, and this one, and had never seen the time when the feeling towards Germany was more favourable and friendly than it was at this last Conference. That there were things that many of the English could not understand, and did not like, but as for any desire to dislike Germany rather than to like her, to be on friendly terms, I could not discover that in conversation with the people or with the Government.

Peace and Security in the British Commonwealth of Nations

Hitler told me he was very pleased to hear me say that. I told him that he or others must not mistake the nature and position of the British Empire; that Canada, for example, was as free and independent a country as Germany itself, but we felt that our freedom was secured in large part by our being a part of the British Empire, that Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand, all felt the same; that each were free to manage their own affairs, and now as long as the British Commonwealth of Nations continued to exist as it now does, that peace and security of all would be greatly strengthened thereby; that if that peace were threatened by an aggressive act of any kind on the part of any country, there was little doubt that all parts would resent it. We valued our freedom above everything else, and anything which would destroy the security of that freedom by destroying any part of the Empire would be certain to cause all carefully to view the whole situation in their own interest and in the interests of the whole.

Hitler said he could understand how that would be. I said there was no thought of aggression on the part of the Empire; and we would not countenance anything of an aggressive nature on our part any more than we would wish to countenance it on the part of others. I stressed very much what freedom meant and pointed out that at the Coronation itself, and at the time of the Great War, there had been no compulsion, that everything was voluntary; that more people would have come to the Coronation had there been hotel and steamboat accommodation. That it was this freedom and liberty which we all prized that was represented in the Crown that kept us united in the way we were.

Herr Hewel had told me that he thought Hitler was allowing at least half an hour for the interview but might run considerably beyond that time. However, as we talked, I saw that we had gone on fully for an hour and that some of those in the room were beginning to give signs to him to think of other engagements. Hitler, however, ignored these and kept up the conversation. Finally I saw that he felt perhaps the interview should close so I hurried to say that there was just one or two more things that I would like to mention expressly to him. One was about Mr. Chamberlain. That I thought Mr. Chamberlain had a good understanding of Foreign Affairs, and had a broad outlook. That I would like to tell him how all of our Ministers and I, myself, had been prejudiced against him on what we thought were narrow views and nationalistic and imperialistic policies, but that we had all come to feel quite differently, and believed policies toward European countries would be wisely administered in his hand. I said his interview the other day with regard to the Leipzig affair was exactly on all fours with what he had said in discussing Germany in the Conference, that I thought it represented his true attitude. Hitler told me he was pleased to know that. I emphasized the necessity of giving time in all matters, to be patient and not hurry on anything. That understanding could be brought about with time.

Hitler Presents a Portrait of Himself as a Gift

As I got up to go, Hitler reached over and took in his hands a red square box with a gold eagle on its cover, and taking it in his two hands, offered it to me, asked me to accept it in appreciation of my visit of Germany. At the same time, he said he had much enjoyed the talk we had had together, and thanked me for the visit. When I opened the cover of the box, I saw it was a beautifully silver mounted picture of himself, personally inscribed. I let him see that I was most appreciative of it, shook him by the hand, and thanked him warmly for it, saying that I greatly appreciated all that it expressed of his friendship, and would always deeply value this gift. He went to give it to someone else to carry but I told him I would prefer to carry it myself. He then drew back a few steps to shake hands and to say good-bye in a more or less formal way. I then said that I would like to speak once more of the constructive side of his work, and what he was seeking to do for the greater good of those in humble walks of life; that I was strongly in accord with it, and thought it would work; by which he would be remembered; to let nothing destroy that work. I wished him well in his efforts to help mankind.

Impressions of Adolf Hitler

I then thanked him again for having given me the privilege of so long an interview. He smiled very pleasantly and indeed has a sort of appealing an affectionate look in his eyes. My sizing up of the man as I sat and talked with him was that he is really one who truly loves his fellowmen, and his country, and would make any sacrifice for their good. That he feels himself to be a deliverer of his people from tyranny.

To understand Hitler, one has to remember his limited opportunities in his early life, his imprisonment, etc. It is truly marvelous what he has attained unto himself through his self education. He reminded me quite a little of Cardin in his quiet way, until he begins to speak when he warms up and begins to get carried away with what he is saying. He has much the same kind of composed exterior with a deep emotional nature within. His face is much more prepossessing than his pictures would give the impression of. It is not that of a fiery, over-strained nature, but of a calm, passive man, deeply and thoughtfully in earnest. His skin was smooth; his face did not present lines of fatigue or weariness; his eyes impressed me most of all. There was a liquid quality about them which indicate keen perception and profound sympathy. He looked most direct at me in our talks together at the time save when he was speaking at length on any one subject; he then sat quite composed, and spoke straight ahead, not hesitating for a word, perfectly frankly, looking down occasionally toward the translator and occasionally toward myself.

When Mr. Schmidt, the translator, was translating part of what he had said, he would turn and look at me sideways and would smile in a knowing way as much as to say you understand what I mean. Similarly when there were bits of humour in what I had said, he would give a look of recognition and smile pleasantly. He has a very nice, sweet [word missing in original -- TML Ed. Note] and, one could see, how particularly humble folk would come to have a profound love for the man. He never once became the least bit restless during the talk of an hour and a quarter which we had together. He sat quietly in an arm chair, with his hands together in front of him, and only when he went to hand me the portrait of himself did he seem to separate them for any length of time. He was wearing an evening dress, white tie, having put on this for receiving personages who had previously called. It was one of the few days he had come into Berlin. He has his offices round about his home in the mountains. He spends most of his time there, very little of it in Berlin, only flies occasionally to the Capital. He feels he needs the quiet and nature to help him to think out the problems of his country. It seems to me that in this he was eminently wise.

Mackenzie King with German officers at the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, Germany, 1937. |

As I talked to him, I could not but think of Joan of Arc. He is distinctly a mystic. Hewel was telling me that the German people, many of them, begin to feel that he has a mission from God, and some of them would seek to reverence him almost as a God. He said Hitler himself tries to avoid that kind of thing. He dislikes any of them thinking of him as anything but a humble citizen who is trying to serve his country well. He is a teetotaler and also a vegetarian; is unmarried, abstemist in all his habits and ways. Indeed his life as one gathers it from those who are closest to him would appear to be that very much of a recluse, excepting that he comes in contact with youth and large number of people from time to time.

Hewel was telling me that when von Ribbentrop had sent for him to fly all the way to Munich to meet Hitler and himself with regard to my visit, and to receive from them instructions as to giving me the fullest information in respect to everything, he said he found Hitler looking very tired during that visit, that he looked [a] much older man. It is very strange, however, that whenever he became interested in a subject, foreign people, all that weariness began to leave him, and he looked young and rested again. He said, for example, that there was a little girl who wanted to get his autograph, the affairs of state would weary him, but when he saw this little child, she changed his whole nature from one of weariness to one of restful joy. He said his passion for the youth of the country is very great.

Hewel tells me he is deeply religious, that he believes strongly in God; as a matter of fact, more congregations had been established in Germany in the last few years than in many years preceding; that the trouble with the Church had been a political trouble, their interference with politics. That the outside world has misrepresented his religious view. That his talks about the race relate to trying to keep the blood of the people pure. That he believes strongly in the physical and mental sides of human natures and necessity for developing both. What he is striving most for is to give to every man the same opportunities as others have in matters of physical development, industrial development, enjoyment, leisure, beauty, etc. He is particularly strong on beauty, loves flowers and will spend more of the money of the State on gardens and flowers than on most other things.

I spoke of liking Mr. Henderson, the British Ambassador, and pointed out to Hitler that he was not to think it strange that the Ambassador was not with me; that that was not a sign of any difference between Great Britain and Canada, but rather a sign of how complete are self-government and mutual trust and confidence. I spoke also of King George having said to me he thought I would like Henderson and of all the expressions that he had used, having been of the friendliest nature towards Germany. (I had in mind in saying it there what Miéville had said to me that the Germans had thought King Edward was their friend as he had been the one who had compelled the visit of British soldiers to Germany. It had never taken place until the King insisted on it, so Miéville said. They were afraid the new King would not be thus friendly).

As I concluded this dictation, I picked up from the table a note which Nicol brought during the dictation but which I did not wish to open till I had concluded what I was saying. It was an envelope having the following words: "Plants from the garden, with best wishes, E.C.D., Ladysford, 29-6-37." It has Mrs. Davidson's card enclosed, and was evidently brought down from the gardener aboard the "Empress" who has taken charge of the plants which were sent to me from Tyrie.

I attach hereto notes of the interview as written out by Pickering independently of myself. They were not read by me prior to dictation, save as to the paragraph re the King, and Pickering had no knowledge of what I was dictating except the introductory part.

Youth Movement, Impressions of Berlin

As we came out of the official residence, a guard of honour was drawn up at the door, also numerous reporters with their cameras. Quite a number of people assembled on the opposite side of the street beyond the gate. Herr Hewel and Pickering drove with me back to the Adlon Hotel, and we had lunch together in a quasi out-of-door restaurant, after which I had a very short rest.

At five o'clock, we left to have a talk with some young people about the youth movement in relation to trips, organized excursions and the effort to have strength through joy, and beauty and industry made general throughout Germany. As was the case wherever we went, some young leader was detailed to meet us at the Hotel, and explain what we were to see and the movement generally. I found all these young men very frank, very alert, clean looking, active minded, enthusiastic young people. There was a splendid order and efficiency about everything we saw. At the offices of these young people, we were given afternoon tea, and then returned to the Hotel to rest before going to the Opera.

I felt that what I would like best of all was a good walk so started off by myself from the Hotel across the Tiergarten, greatly enjoying en route the statue of the wounded lion with its mate and cubs. I noticed the date it was constructed as 1874, the year of my birth; having reached the far side of the Tiergarten, I tried to discover the house where I lived with the Webers in Berlin. By asking questions, I was directed along different streets, recognizing the canal and other features, and finally came to the house itself where I picked some leaves from the hedge around the corner, and recalled some of the feelings I had when residing there 37 years ago. In particular, I thought much of how fortunate I was to have so good a friend in Mr. Dickie. It was clear that I had gotten into one of the best parts of Berlin, and into the home of an exceptionally fine family. It was to father's friendship with Mr. Dickie that I owed this exceptional advantage. I continued my walk back through the Tiergarten, reaching the Hotel about 7.20, having walked at least 5 or 6 miles.

During this walk, I enjoyed exceedingly being in the woods, and listening to the birds singing, and felt a real sense of rejoicing from the way in which the interview had gone and the good, I believed, it was going to serve. Once back to the Hotel, there was only time to dress before leaving for the Opera House a little before eight o'clock.

At the Opera, Harmony and Joy

At the Opera, I was received by a couple of members of General Göring's staff who were more than politeness and kindness itself. We were given what would be the royal box in the old days which comprises pretty much the center end of the first gallery immediately opposite the stage. I was given the seat in the center where the Emperors used to sit and where Hitler sits when he attends the Opera. As we went into our seats, word seemed to go quickly around the audience for nearly everybody turned and looked toward the box, I was impressed by the fact that those enjoying the Opera were those who seemed to have gone for the love of music, etc., rather than for social reasons, for dress was conspicuous by its absence rather than its presence. Every seat in the house, balconies, galleries, et cetera, were taken. I was told it was the same at all performances. The play was "The Masked Ball". It was exceptionally well performed; beautiful singing; excellent staging; many lovely tableaux. Between the 3rd and 4th acts, we were taken out to a special supper, arranged in the large hall in a little space adjoining the box which had been partitioned off by shrubs and trees. Sir Ogilvie Forbes and his wife, Pickering, Hewel, and myself, and members of General Göring's staff were present. One of the men I talked to I found exceptionally sympathetic. He spoke about secret forces at work to bring about better conditions after this period of stress and strain.

I returned to the Hotel after what Pickering has said was perhaps the most significant day in my life. Tired but feeling that nothing could have better concluded the day than the glorious music and singing which seemed to fill the entire Opera House with harmony and joy. The last scene seemed to bring invisible numbers of persons who joined in the chorus which closed the life of one who was playing the leading part. A triumphal end to it all.

Notes

1. "Mackenzie

King

in

Berlin,"

Library

and Archives Canada.

2. Ibid.

(Photos: Library and Archives Canada)

Dachau Concentration Camps

The First Prisoners Were Political

Opponents

of the Regime

On March 21, 1933, the Munich Chief of Police, Heinrich Himmler, ordered that a concentration camp be erected at Dachau. According to the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial website:

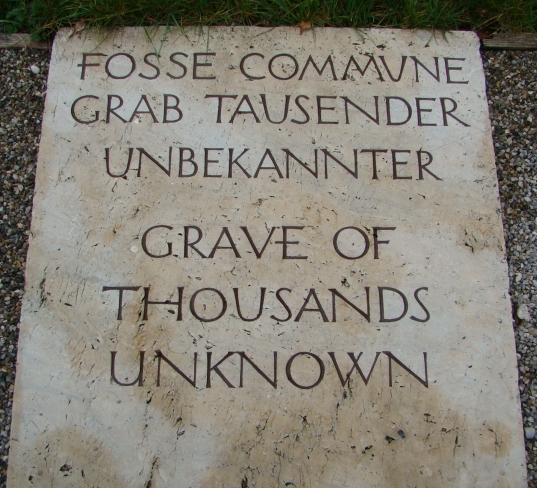

Marker for a mass grave at the former Dachau concentration camp. |

"In June 1933, Theodor Eicke was appointed commandant of the concentration camp. He developed an organisational plan and rules with detailed stipulations, which were later to become valid for all concentration camps. Also from Eicke came the division of the concentration camp into two areas, namely the prisoners' camp surrounded by a variety of security facilities and guard towers and the so-called camp command area with administrative buildings and barracks for the SS.

"Later appointed to the position of Inspector for all Concentration Camps, Eicke established the Dachau concentration camp as the model for all other camps and as the murder school for the SS."

The website continues: "The first prisoners were political opponents of the regime, communists, social democrats, trade unionists, also occasionally members of conservative and liberal political parties. The first Jewish prisoners were also sent to the Dachau concentration camp because of their political opposition."

We reproduce below an article from the archives of the Manchester Guardian, forerunner to the Guardian, dated March 21, 1933 which carried the headline "Communists to be interned at Dachau."

***

The President of the Munich police has informed the press that the first concentration camp holding 5,000 political prisoners is to be organised within the next few days near the town of Dachau in Bavaria.

Here, he said, Communists, "Marxists," and Reichsbanner leaders who endangered the security of the State would be kept in custody. It was impossible to find room for them all in the State prisons, nor was it possible to release them. Experience had shown, he said, that the moment they were released they always started their agitation again. If the safety and order of the State were to be guaranteed such measures were inevitable, and they would be carried out without any petty considerations. [Himmler's statement went on to say: "...continual inquiries as to the date of release of individual protective custody prisoners will only hinder the police in their work."][1]

This is the first clear statement hitherto made regarding concentration camps. The extent of the terror may be measured from the size of this Bavarian camp -- which, one may gather, will be only one of many.

The Munich police president's statement leaves no more doubt whatever that the Socialists and Republicans will be given exactly the same sort of "civic education" as the Communists. It is widely held that the drive against the Socialists will reach its height after the adjournment of the Reichstag next week.

TML Note

1. Source: Concentration Camp Dachau, 1933-1945, Editors: Barbara Distel, Ruth Jakusch, Publisher: International Committee of Dachau, 1978.

(Workers' Daily Internet Edition. Photo: Alison W.)

"Operation Unthinkable"

Churchill's Planned Invasion

of the

Soviet

Union, July 1945

In late May 1945, Josef Stalin ordered Marshall Georgy Zhukov to leave Germany and come to Moscow. He was concerned over the actions of British allies. Stalin said the Soviet forces disarmed Germans and sent them to prisoners' camps while the British did not. Instead they cooperated with German troops and let them maintain combat capability. Stalin believed that there were plans to use them later. He emphasized that it was an outright violation of the inter-governmental agreements that said the forces surrendered were to be immediately disbanded. The Soviet intelligence got the text of a secret telegram sent by Winston Churchill to Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, the commander of British forces. It instructed to collect the weapons and keep them in readiness to give back to Germans in case the Soviet offensive continued.

According to the instructions received from Stalin, Zhukov harshly condemned these activities when speaking at the Allied Control Council (the Soviet Union, the United States, the United Kingdom and France). He said world history knew few examples of such treachery and refusal to observe the commitments on the part of nations that had an allied status. Montgomery denied the accusation. A few years later he admitted that he received such an instruction and carried it out. He had to comply with the order as a soldier.

A fierce battle was raging in the vicinity of Berlin. At this time, Winston Churchill said that the Soviet Russia had become a deadly threat to the free world. The British Prime Minister wanted a new front created in the east to stop the Soviet offensive as soon as possible. Churchill was overwhelmed by the feeling that with Nazi Germany defeated a new threat emerged posed by the Soviet Union.

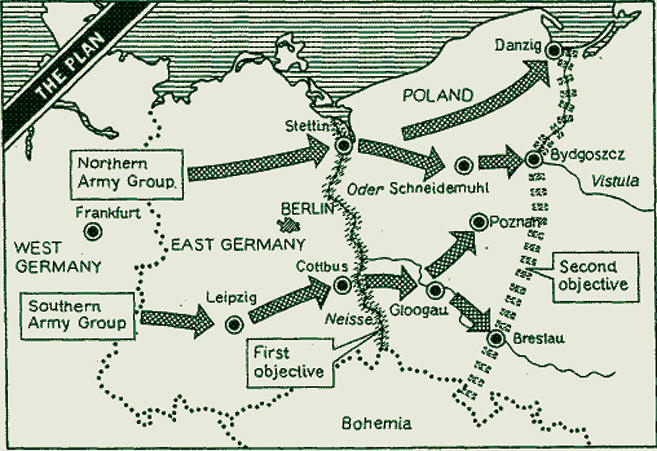

Report by Joint Planning Staff on Operation Unthinkable, May 22, 1945. |

That's why London wanted Berlin to be taken by Anglo-American forces. Churchill also wanted Americans to liberate Czechoslovakia and Prague with Austria controlled by all allies on equal terms.

Not later than April 1945 Churchill instructed the British Armed Forces' Joint Planning Staff to draw up Operation Unthinkable, a code name of two related plans of a conflict between the Western allies and the Soviet Union. The generals were asked to devise means to "impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire." The hypothetical date for the start of the Allied invasion of Soviet-held Europe was scheduled for July 1, 1945. In the final days of the war against the Hitler's Germany London started preparations to strike the Soviet Union from behind.

The plan envisioned unleashing a total war to occupy the parts of the Soviet Union which had a crucial significance for its war effort and deliver a decisive blow to the Soviet armed forces leaving the USSR unable to continue fighting.

The plan included the possibility of Soviet forces retreating deep into its territory according to the tactics used in previous wars. The plan was taken by the British Chiefs of Staff Committee as militarily unfeasible due to a three-to-one superiority of Soviet land forces in Europe and the Middle East, where the conflict was projected to take place. German units were needed to balance the correlation of forces. That's why Churchill wanted them to remain combat capable.

The War Cabinet stated: "The Russian Army has developed a capable and experienced High Command. The army is exceedingly tough, lives and moves on a lighter scale of maintenance than any Western army, and employs bold tactics based largely on disregard for losses in attaining its objective. Equipment has improved rapidly throughout the war and is now good. Enough is known of its development to say that it is certainly not inferior to that of the great powers. The facility the Russians have shown in the development and improvement of existing weapons and equipment and in their mass production has been very striking. There are known instances of the Germans copying basic features of Russian armament." The British planners came to pessimistic conclusions. They said any attack would be "hazardous" and that the campaign would be "long and costly". The report actually stated: "If we are to embark on war with Russia, we must be prepared to be committed to a total war, which would be both long and costly." The numerical superiority of Soviet ground forces left little chance for success. The assessment, signed by the Chief of Army Staff on June 9, 1945, concluded: "It would be beyond our power to win a quick but limited success and we would be committed to a protracted war against heavy odds. These odds, moreover, would become fanciful if the Americans grew weary and indifferent and began to be drawn away by the magnet of the Pacific war."

The Prime Minister received a draft copy of the plan on June 8th. Annoyed as he was, Churchill could not do much about it as the supremacy of the Red Army was evident. Even with a nuclear bomb in the inventory of US military, Harry Truman, the new American President, had to take it into account.

Meeting Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, President Truman took the bull by the horns. He made a thinly veiled threat to use economic sanctions against the Soviet Union. On May 8, the U.S. President ordered the lend-lease supplies [military aid] be greatly reduced, without prior notification. It went as far as the return of U.S. ships, already on the way to the Soviet Union, back to their home bases. Some time passed and the order to reduce the lend lease was cancelled otherwise the Soviet Union would not have joined the war against Japan, something the United States needed. But the bilateral relationship was damaged. The memorandum signed by Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew on May 19, 1945 stated that war with the Soviet Union was inevitable. It called for taking a tougher stand in the contacts with the Soviet Union. According to him, it was expedient to start the fighting before the USSR could recover from war and restore its huge military, economic and territorial potential.

The military received an impulse from politicians. In August 1945 (the war with Japan was not over) the map of strategic targets in the USSR and Manchuria was submitted to General L. Groves, the head of the U.S. nuclear program. The plan contained the list of the 15 largest cities of the Soviet Union: Moscow, Baku, Novosibirsk, Gorky, Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk, Omsk, Kuibyshev, Kazan, Saratov, Molotov (Perm), Magnitogorsk, Grozny, Stalinsk (probably Stalino -- the contemporary Donetsk) and Nizhny Tagil. The targets were given descriptions: geography, industrial potential and the primary targets to hit. Washington opened a new front. This time it was against its ally.

London and Washington immediately forgot they fought shoulder to shoulder with the Soviet Union during the Second World War, as well as their commitments according to the agreements reached at the Yalta, Potsdam and San Francisco conferences.

(Strategic Culture Foundation, May 25, 2015. Slightly edited for grammar by TML.)

U.S. Recruitment of Nazi War Criminals

The Abhorent "Stay-Behind" Legacy

TML is posting below an excerpt from an article by Martin A. Lee entitled "The CIA's Neo-Nazis: Strange Bedfellows Boost Extreme Right in Germany," originally published in Intellectual Capital (U.S.), No 377, May 25, 2000. It details the "stay behind" anti-communist forces established by the Western powers in Europe during the Cold War. Such units typically included fascists and former Nazis and targeted progressive forces and those thought to be sympathetic to communism.

***

[...] West German "stay behind" forces [although exposed in 1952] quickly regrouped with a helping hand of the CIA, which recruited thousands of ex-Nazis and fascists to serve as Cold War espionage assets. "It was a visceral business of using any bastard as long as he was anti-Communist," explained Harry Rostizke, ex-head of the CIA's Soviet desk. "The eagerness to enlist collaborators meant that you didn't look at their credentials too closely."

The key player on the German side of this unholy espionage alliance was Gen. Reinhard Gehlen, who served as Adolf Hitler's top anti-Soviet spy. During World War II, Gehlen was in charge of German military-intelligence operations on the eastern front.

As the war drew to a close, Gehlen sensed that the United States and USSR would soon be at loggerheads. He surrendered to the Americans and touted himself as someone who could make a decisive contribution to the impending struggle against the Communists. Gehlen offered to share the vast information archive he had accumulated on the USSR.

U.S. Spymasters Took the Bait

With a mandate to continue spying on the East just as he had been doing before, Gehlen re-established his espionage network at the behest of American intelligence. Incorporated into the fledgling CIA in the late 1940s, the Gehlen "Org," as it was called, became the CIA's main eyes and ears in Central Europe.

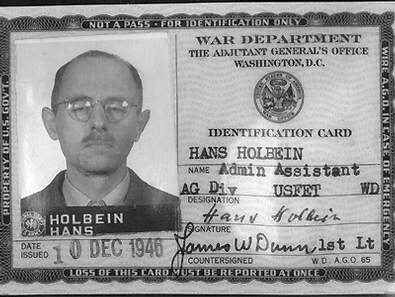

False papers issued to Nazi war criminal Reinhard Gehlen by the U.S. War Department. |

Despite his promise not to recruit unrepentant Nazis, Gehlen rolled out the welcome mat for thousands of Gestapo, Wehrmacht and SS veterans. Some of the worst war criminals imaginable -- including cold-blooded bureaucrats who oversaw the administrative apparatus of the Holocaust -- found employment in the Org. Headquartered near Munich, the Org subsequently morphed into the Bundesnachtrichtendienst, West Germany's main foreign intelligence service. Gehlen was appointed the first director of the BND in 1955.

While dispensing data to his avid American patrons, Gehlen helped thousands of fascist fugitives escape to safe havens abroad -- often with a wink and a nod from U.S. intelligence.

Third Reich expatriates subsequently served as "security advisers" to repressive regimes in Latin America and the Middle East. Ironically, some of Gehlen's recruits would later play leading roles in neo-fascist groups around the world that despised the United States and the NATO alliance.

Friedhelm Busse went on to direct several ultra-right-wing groups in Germany, while another Gehlen protégé, Gerhard Frey, also emerged as a mover-and-shaker in the post-Cold War neo-Nazi scene. A wealthy publisher, Frey currently bankrolls and runs the Deutsche Volksunion (DVU), which was described by U.S. army intelligence as "a neo-Nazi party." During the past two years, the DVU scored double-digit vote totals in state elections in eastern Germany, where the whiplash transition from Communism to capitalism has resulted in high unemployment and widespread social discontent. Embittered by the disappointing reality of German unification, a lost generation of East German youth comprise a Nazi Party in waiting.

Even before Frey formed the DVU in 1971 with the professed objective to "save Germany from Communism," he received behind-the-scenes support from Gehlen, Bonn's powerful spy chief. But when the Cold War ended, the DVU chief abruptly shifted gears and demanded that Germany leave NATO. Frey's newspapers started to run inflammatory articles that denounced the United States and praised Russia as a more suitable partner for reunified Germany. Frey also joined the chorus of neo-fascist leaders who backed Saddam Hussein and condemned the U.S.-led war against Iraq in 1991.

A Deal with the Devil

In American spy parlance, it is called "blowback" -- the unintended consequences of covert activity kept secret from the US public. The covert recruitment of a Nazi spy network to wage a shadow war against the Soviet Union was the CIA's "original sin," and it ultimately backfired against the United States. An unforeseen consequence of the CIA's ghoulish tryst with the Org is evident today in a resurgent neo-fascist movement in Europe that can trace its ideological lineage back to Hitler's Reich through Gehlen operatives who served US intelligence. Moreover, by subsidizing a top Nazi spymaster and enlisting badly compromised war criminals, the CIA laid itself open to manipulation by a foreign intelligence service that was riddled with Soviet agents.

"One of the biggest mistakes the United States ever made in intelligence was taking on Gehlen," a CIA official later admitted. With that fateful sub rosa embrace, the stage was set for Washington's tolerance of human-rights abuses and other dubious acts in the name of anti-Communism.

Read The Marxist-Leninist

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

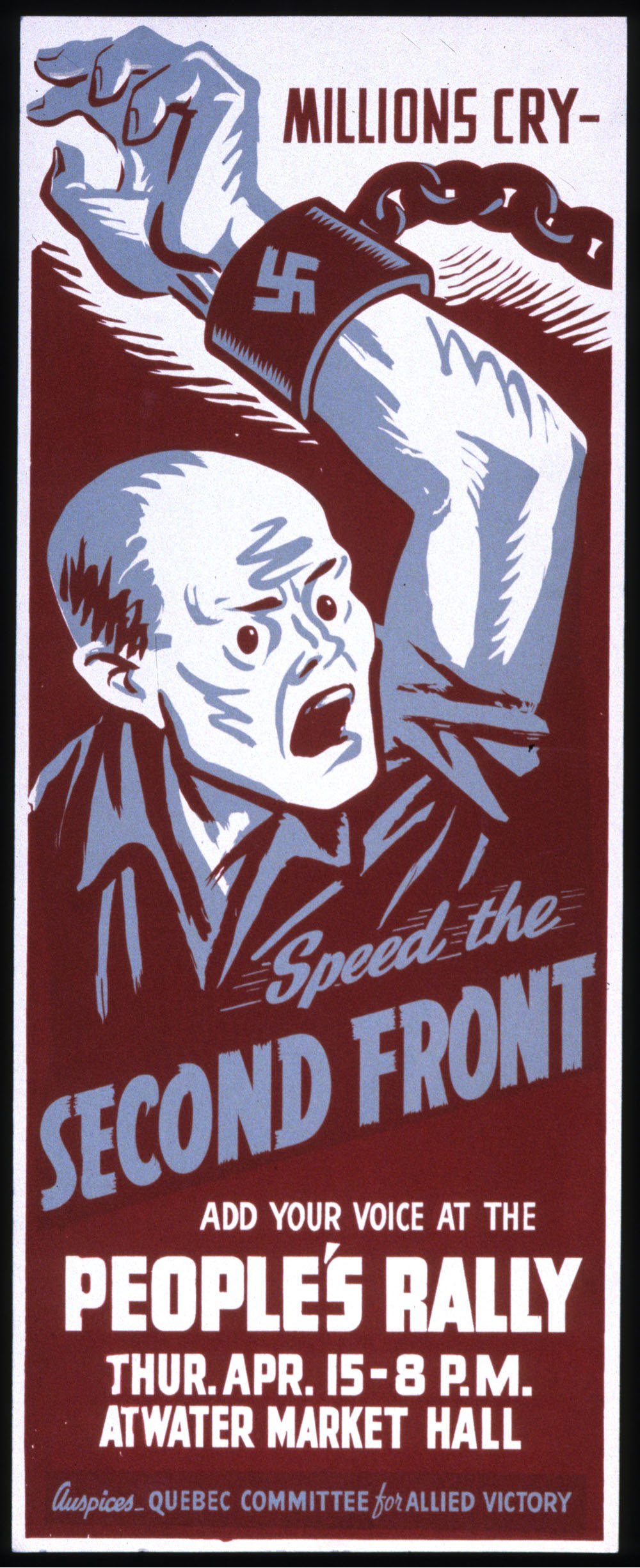

Roosevelt could see advantages to

not opening up a Second Front. It

allowed the U.S. ruling circles to commit more manpower and equipment

to

the war in the Pacific, where the economic and strategic interests of

the U.S.

were more directly at stake than in Europe. Roosevelt and his military

and

political advisors also realized that defeating Germany would require

huge

sacrifices, which they feared the American people might not support. A

landing in Europe would lead to a bloody and costly battle with Nazi

Germany. By avoiding engagement in a Second Front, the U.S. and their

British Allies could minimize their losses, then intervene when both

Germany

and the Soviet Union were exhausted. The U.S., with its British ally,

could

then create a post-war Europe that was to its own economic and

political

advantage.

Roosevelt could see advantages to

not opening up a Second Front. It

allowed the U.S. ruling circles to commit more manpower and equipment

to

the war in the Pacific, where the economic and strategic interests of

the U.S.

were more directly at stake than in Europe. Roosevelt and his military

and

political advisors also realized that defeating Germany would require

huge

sacrifices, which they feared the American people might not support. A

landing in Europe would lead to a bloody and costly battle with Nazi

Germany. By avoiding engagement in a Second Front, the U.S. and their

British Allies could minimize their losses, then intervene when both

Germany

and the Soviet Union were exhausted. The U.S., with its British ally,

could

then create a post-war Europe that was to its own economic and

political

advantage.