|

April 18, 2015 - No. 16 Supplement A Review of Harper's Attempts to

|

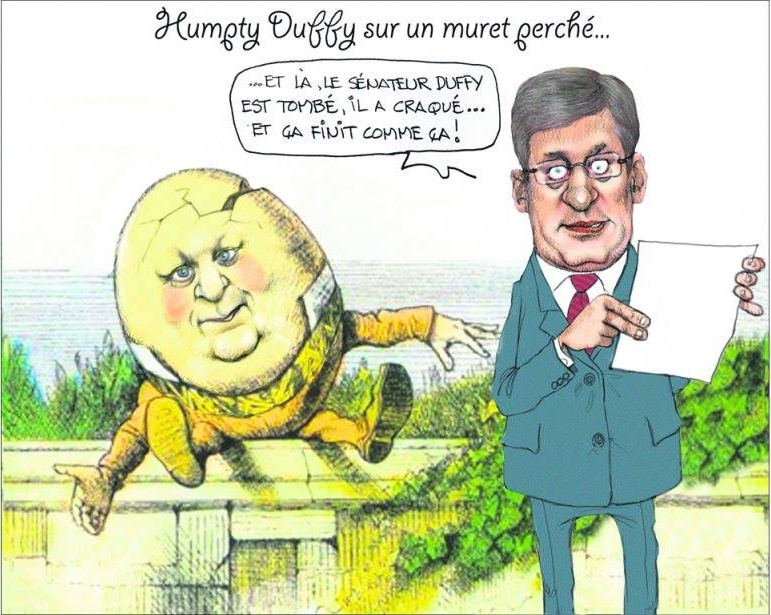

La Presse cartoon of the Humpty Duffy affair. Harper says: "Humpty Duffy sat on a wall... and then Senator Duffy fell down and was cracked ... and that is the end of the story." |

Another issue revealed within this scandal is the manner

in

which private monopoly interests concentrated in the PMO

have used the Harper majority and its executive to take even greater

absolute

control

of the government. Using the power of the executive, private interests

have

extended their control over the institutions of the Canadian state

within and

outside Parliament, as well as over the cartel party system, in

particular the

Conservative Party. From this position, these private monopoly

interests push

their narrow self-serving agendas in the name of public interest or

national

security and destroy those public institutions, regulations and

traditions that

operate as a block or restrict their power.

According to lawyers for Nigel Wright, as revealed in the same affidavit of the lead RCMP investigator, one of Wright's roles within the Prime Minister's Office was to "manage the Conservative Party, part of which was to deal with matters that could cause embarrassment." This makes clear that his role in dealing with Duffy's "embarrassing" expense claims was not a one-off incident but part of his assigned duties within the PMO, likely so that Harper himself can claim bogus "plausible deniability."

To deal with the "embarrassing situation," and this shows how scandal usually goes hand in hand with blackmail, the Conservative Party intended to cover Duffy's expenses from a Conservative fund overseen by Senator Irving Gerstein. This plan was hatched when it was thought the expenses were in the range of $32,000. However, when it became apparent the amount was $90,124.27, the affidavit states that party officials felt the figure was "too much" for the fund to cover. It may well have been "too much" as it would have raised too many questions. Instead, Wright paid Duffy himself on the condition that he repay the money immediately and not speak to the media about it further.

Nigel Wright is a known quantity. He has definite connections with private monopoly interests. He was the managing director of Onex Corporation, a large private equity investment firm and holding company owned by billionaire Gerry Schwartz. He also has other direct links to monopoly interests in the mining sector such as Barrick Gold. Wikipedia calls him "a prominent Bay Street dealmaker," "a Bay Street heavy hitter."

In all of this, the fact that Wright, an official of the PMO and a public servant, is the manager of the Conservative Party on behalf of the PMO indicates the extent to which he, as a representative of definite private interests is in a position to determine or at the very least strongly influence Conservative Party affairs. At the same time, he oversaw the Office of the Prime Minister, a position that has usurped the decision-making functions of the government, the House of Commons, and the Parliament as a whole.[3]

The Necessity for the Working Class to Put Itself

at the Head of

Nation-Building

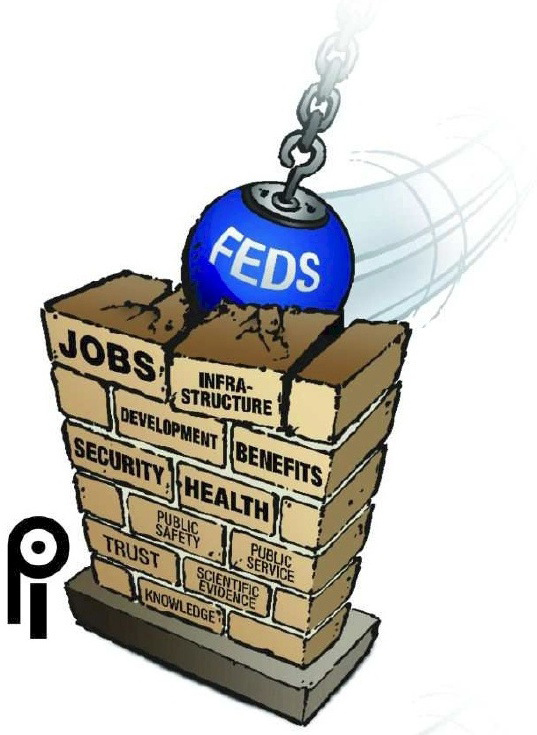

The actions of the Harper government

reveal that it is prepared

to wreck anything that stands in the way of monopoly right, including

Canada

itself. Harper's main attack is on the thinking

of the Canadian working class and others to make them

feel

as if they are powerless in the face of his wrecking ball.

The Harper way is presumably

the only way to get things

done, and in the face of his executive power and prerogative, he wants

everyone to believe and accept that there is no alternative.

The Harper way is presumably

the only way to get things

done, and in the face of his executive power and prerogative, he wants

everyone to believe and accept that there is no alternative.

But that is not the case. The Canadian and Quebec working class and the First Nations have a future because they stand for nation-building and not nation-wrecking. The Harperites have no future because their self-serving agenda is in contradiction with the public interest and the progressive trend of history.

The current scandal is a result of the Harperites self-serving agenda to enshrine monopoly right as dictator with absolute power over public right. Such an agenda has no place in the modern world and will continue to unravel especially when faced with an increasingly outraged, conscious and organized polity.

By putting forward its independent politics in various new ways, the working class is gaining invaluable experience in the practical politics of how to establish new mechanisms to unite all those who can be united behind a pro-social program of nation-building. In the course of the fight to present its own pro-social program and stop the Harper anti-social offensive, the working class must take up the central question of the democratic renewal of Canada's institutions so that Canadians, Québécois and the First Nations can unleash the human factor of the collectives of the people from coast to coast.

Notes

1. Some of the allegations of

inappropriate

expenses concern Duffy

claiming a Senate living allowance for a

secondary residence in Ottawa. Within this, he claims his primary

residence is in

PEI,

which he represents. According to a sworn affidavit by an RCMP

investigator,

Duffy himself was concerned that if it became clear through a Senate

investigation that PEI is not his primary residence his Senate seat

might be in

question.

According to the same affidavit, Duffy's

concerns were allayed by the

Prime Minister's Chief of Staff, Nigel Wright. The Senate requires that

Senators reside in the province for which they were appointed, but it

does

not necessarily have to be their primary residence. In other words,

Duffy's seat

is safe although his claim that PEI is his primary residence more and

more is

being shown to be completely bogus, to the extent that it was revealed

in the

affidavit that Duffy has lived in Ottawa since 1971, some 42 years ago.

2. Section 21 and 22 of the Canadian

Constitution relating to

the constitution

of the Senate and criteria of membership therein:

Representation of Provinces in Senate

22. In relation to the Constitution of the Senate Canada shall be deemed to consist of Four Divisions:

1. Ontario;

2. Quebec;

3. The Maritime Provinces, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and Prince

Edward Island;

4. The Western Provinces of Manitoba, British Columbia, Saskatchewan,

and Alberta;

which Four Divisions shall (subject to the Provisions of this Act) be equally represented in the Senate as follows: Ontario by twenty-four senators; Quebec by twenty-four senators; the Maritime Provinces and Prince Edward Island by twenty-four senators, ten thereof representing Nova Scotia, ten thereof representing New Brunswick, and four thereof representing Prince Edward Island; the Western Provinces by twenty-four senators, six thereof representing Manitoba, six thereof representing British Columbia, six thereof representing Saskatchewan, and six thereof representing Alberta; Newfoundland shall be entitled to be represented in the Senate by six members; the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut shall be entitled to be represented in the Senate by one member each.

In the Case of Quebec each of the Twenty-four Senators representing that Province shall be appointed for One of the Twenty-four Electoral Divisions of Lower Canada specified in Schedule A. to Chapter One of the Consolidated Statutes of Canada. (12)

Marginal note: Qualifications of Senator

23. The Qualifications of a Senator shall be as follows:

(1) He shall be of the full age of Thirty Years;

(2) He shall be either a natural-born Subject of the Queen, or a Subject of the Queen naturalized by an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, or of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, or of the Legislature of One of the Provinces of Upper Canada, Lower Canada, Canada, Nova Scotia, or New Brunswick, before the Union, or of the Parliament of Canada after the Union;

(3) He shall be legally or equitably seised as of Freehold for his own Use and Benefit of Lands or Tenements held in Free and Common Socage, or seised or possessed for his own Use and Benefit of Lands or Tenements held in Franc-alleu or in Roture, within the Province for which he is appointed, of the Value of Four thousand Dollars, over and above all Rents, Dues, Debts, Charges, Mortgages, and Incumbrances due or payable out of or charged on or affecting the same;

(4) His Real and Personal Property shall be together worth Four thousand Dollars over and above his Debts and Liabilities;

(5) He shall be resident in the Province for which he is appointed;

(6) In the Case of Quebec he shall have his Real Property Qualification in the Electoral Division for which he is appointed, or shall be resident in that Division.

3. Harper once described in an interview the way his government functions. The "team" in his office, which is reportedly made up of roughly 1,000 private consultants, comes up with proposals that are presented to the Cabinet for feedback. Once decided, the proposals are given to Conservative MPs to take to the public.

Supreme Court Ruling

A Primer on What Is the Senate;

What Are the Amending

Formulas;

Why Are There Such Amending Formulas

A Review of Harper's Attempts to Reform the Senate

In the campaign for the January 23, 2006 federal election, then Leader of the Opposition Stephen Harper said he would reform the Senate. Ever since the Harper Conservatives have attempted to push various Senate reform bills through the Parliament in the name of "the people" and/or the Harperites' claim to "a mandate." From the get-go, the Harper Conservatives' campaign of Senate reform was based on a lawless premise that Senate reform can be realized without opening up the Constitution.

Accordingly, the Harper

Conservatives have attempted on

several occasions to unilaterally reform the Senate. These

efforts have nothing to do with reforming Canada's archaic and

anachronistic political institutions so as to bring them into

conformity with the requirements of a modern democratic system

that would enable the people to participate in governance. If

ever implemented they would further subordinate the Senate to the

corrupt cartel-party system, even beyond the level of corruption

currently on display.

Accordingly, the Harper

Conservatives have attempted on

several occasions to unilaterally reform the Senate. These

efforts have nothing to do with reforming Canada's archaic and

anachronistic political institutions so as to bring them into

conformity with the requirements of a modern democratic system

that would enable the people to participate in governance. If

ever implemented they would further subordinate the Senate to the

corrupt cartel-party system, even beyond the level of corruption

currently on display.

From 2006 through to April 2011 while in a minority position, the Harperites' efforts to transform the Senate while circumventing constitutional methods were blocked by the opposition. Their first attempt was in the Senate in May 2006, with the introduction of Bill S-4, An Act to Amend the Constitution (Senate Tenure); followed by C-43, Senate Appointment Consultations Act, introduced in the House of Commons on December 13, 2006. The review conducted by the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on Bill S-4 stopped the legislation because of concerns about constitutional legitimacy. In addition, the approach of splitting the two aspects of the reforms -- Senate tenure and optional consultative elections -- into two pieces of legislation, one through the Senate and one through the House of Commons, caused a lot of concern about what the Harper government was up to. Constitutional experts and representatives of provincial and territorial governments who appeared before the Senate Committee did not mince words.

On March 29, 2007 constitutional law Professor Errol Mendes told the Committee:

"It is generally known that Bill S-4 is only a precursor to a larger attempt to have future appointments to the Senate come under a federally regulated advisory elections framework. In my view, if the two statutes or two attempts are linked, it profoundly is unconstitutional.

"In my view, this is an attempt to do what cannot be done directly without the clear instructions of section 42 and the general amending formula. Keep in mind that the Patriation Reference decision in 1981 informed the then Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, that he would breach constitutional convention if he repatriated the Constitution without the substantial consent of the provinces [...] and the rest is history.

"In the development of the federal advisory elections of the Senate, we have a much more serious attempt linked to Bill S-4. This does indirectly what cannot be done directly, both under constitutional conventions and under the Constitution Act, 1867 and 1982, without the involvement of provinces and provincial consent.

[...]

"In conclusion, with all the arguments I have presented, there is good reason to suggest that Bill S-4 should be withdrawn until further study is undertaken to understand what is really at stake in this piecemeal and dubious attempt to reform the Senate so that it is consistent with the principles of modern democracy."

In its written submission to the Senate Committee, the Quebec government stated: "In summary [...] the federal legislative initiative represented by Bills S-4 and C-43 is liable to modify the nature and role of the Senate, in a manner which departs from the original pact of 1867.

"Such changes are beyond the unilateral powers of the Parliament of Canada. They instead require a coordinated constitutional amendment formula, which in turn requires the participation and consent of the provinces.

"The well-known legal rule that one may not do indirectly what cannot be done directly fully applies to the amendment process that is in question here with bills S-4 and C-43.

"The Government of Quebec is not opposed to modernizing the Senate. But if the aim is to alter the essential features of that institution, the only avenue is the initiation of a coordinated federal-provincial constitutional process that fully associates the constitutional players, one of them being Quebec, in the exercise of constituent authority.

"The Government of Quebec, with the unanimous support of the National Assembly, therefore requests the withdrawal of Bill C-43. It also requests the suspension of proceedings on Bill S-4 so long as the federal government is planning to unilaterally transform the nature and role of the Senate."

As in the case with Bill C-51, the Anti-Terrorism Act 2015, the Harper government refused to acknowledge the well-reasoned and expert opinion on the constitutionality of its proposed Senate reform legislation. The Harperites continued to push. In November 2007, the Harper government introduced C-20, for consultative Senate elections, and C-10, to eliminate life-tenure. Both bills died at the dissolution of the Parliament in 2008. Again, in May 2009, Bill S-7 was introduced to set an eight-year limit to senatorial terms, but it could not get past second reading. March 29, 2010, C-10 was introduced in the House of Commons with the same objective of setting eight-year terms, but it also couldn't get past second reading. S-8 for senatorial election was introduced in April 2010 but it died at dissolution of the Parliament in April 2011.

After the 2011 Electoral Coup

After its electoral coup of May 2011, the Harper government introduced the Senate Reform Act on June 21, 2011. It would have set nine-year term limits for anyone appointed to the Senate after October 2008 and created a voluntary framework for provinces that wanted to hold Senate nominee elections.

Introducing the legislation, then Minister of Democratic Reform Tim Uppal stated:

"After receiving a strong

mandate from Canadians, our

Government is taking action on our commitment to make the Senate

more democratic, accountable, and representative of Canadians.

With the Senate Reform Act [...] our Government is

proposing measures that will give Canadians a say in the

selection of their Senate nominees and will limit new senators to

one nine-year term."

"After receiving a strong

mandate from Canadians, our

Government is taking action on our commitment to make the Senate

more democratic, accountable, and representative of Canadians.

With the Senate Reform Act [...] our Government is

proposing measures that will give Canadians a say in the

selection of their Senate nominees and will limit new senators to

one nine-year term."

As the legislation made its way through the House of Commons with continuing opposition, on April 30, 2012 the Quebec government presented the proposed Senate Reform Act to the Quebec Court of Appeal, requesting a reference on its constitutionality. On February 1, 2013 the Conservative government itself asked the Supreme Court of Canada for a reference on how to reform the Senate, including how it could be abolished.

Speaking at a press conference at the time of filing the request for a Supreme Court Reference on Senate reform, Democratic Reform Minister Pierre Poilievre said that the Supreme Court's opinion "will allow us to move forward by providing clarity on the appropriate amendment procedures." He added that "The Senate must either be reformed or like its provincial counterparts it must be abolished. This reference to the court will give Canadians a series of legal options and maybe even a how-to-guide on how to pursue them. And once we hear back from the top court we can take direction from Canadians on how to do so."

The Quebec Court of Appeal issued its ruling on October 24, 2013, unequivocally rendering the attempt to unilaterally reform the Senate unconstitutional. As expected, the Harper government responded to the Quebec ruling by saying that it would wait for the Supreme Court Reference before deciding how to proceed.

Barely two hours after the Supreme Court issued its 73-page ruling on April 25, 2014 outlining that Senate reform must follow the rules of the Constitution and explaining what those rules are, the Harper government made it clear that the "how-to-guide" that Poilievre referred to was going to be scattered to the wind. Prime Minister Harper tried to present the Supreme Court, not his lawlessness, as the obstacle to Senate reform.

He told reporters in Kitchener: "The Supreme Court essentially said today that for any important reform of any kind, as well as abolition, these are only decisions that provinces can take." Harper stated: "We know that there is no consensus among the provinces on reform, no consensus on abolition, and no desire of anyone to reopen the Constitution and have a bunch of constitutional negotiations."

"So, essentially this is a decision for the status quo, a status quo that is supported by virtually no Canadian. We're essentially stuck with the status quo for the time being." Harper told reporters that "Significant reform and abolition are off the table. I think it's a decision that I'm disappointed with. But I think it's a decision that the vast majority of Canadians will be very disappointed with. But obviously we will respect that decision."

The Senate References of the Quebec Court of Appeal and

the

Supreme Court of Canada

Both the Supreme Court of Canada and the Quebec Court of Appeal have ruled that reforms to the Senate that would introduce elections as a part of the senatorial appointment process or change the life-appointment of senators to term appointments would require adherence to Subsection 38(1) of the Constitution.

Subsection 38(1) states:

"38. (1) [General procedure for amending Constitution of Canada] An amendment to the Constitution of Canada may be made by proclamation issued by the Governor General under the Great Seal of Canada where so authorized by

(a) resolutions of the Senate and House of Commons; and

(b) resolutions of the legislative assemblies of at least two-thirds of the provinces that have, in the aggregate, according to the then latest general census, at least fifty per cent of the population of all the provinces." [Referred to as the 7/50 formula -- TML Ed. Note.]

As for abolition of the Senate, the Supreme Court ruled that it would require resolutions by the House of Commons, the Senate and the consent of all provinces and territories.

This is based on the application of Section 42(1) of the Constitution which states:

"An amendment to the Constitution of Canada in relation to the following matters may be made only in accordance with subsection 38(1):

[...]

(b) the powers of the Senate and the method of selecting Senators;

(c) the number of members by which a province is entitled to be represented in the Senate and the residence qualifications of Senators."

In its succinct conclusion, the Supreme Court stated:

"The majority of the changes to the Senate which are contemplated in the Reference can only be achieved through amendments to the Constitution, with substantial federal-provincial consensus. The implementation of consultative elections and senatorial term limits requires consent of the Senate, the House of Commons, and the legislative assemblies of at least seven provinces representing, in the aggregate, half of the population of all the provinces: s. 38 and s. 42(1)(b), Constitution Act, 1982. A full repeal of the property qualifications requires the consent of the legislative assembly of Quebec: s. 43, Constitution Act, 1982. As for Senate abolition, it requires the unanimous consent of the Senate, the House of Commons, and the legislative assemblies of all Canadian provinces: s. 41(e), Constitution Act, 1982."

These conclusions are based on an examination of the nature of the Senate within the overall institution of governance, and Canada's Constitution and its development.

In its October 2013 ruling, the Quebec Court of Appeal provided the following institutional context to Senate reform:

"Canada's founding fathers sought to implant a parliament modeled on that of the United Kingdom (see the preamble to the Constitution Act, 1867). Accordingly, there were two legislative houses, the lower one also called the House of Commons and the upper one, called the Senate, since the British colonies of North America did not have an established nobility that could constitute a legislative chamber such as the House of Lords.

"These two institutions enjoy the same privileges, immunities and powers as those recognized at the time by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and by its members (section 18, Constitution Act, 1867). In law their powers were identical, save with respect to bills involving the expenditure of public funds or the imposition of taxes (section 53, Constitution Act, 1867) and some constitutional amendments (section 47, Constitution Act, 1982).

"The transcript of the pre-confederation conferences shows that the founding fathers discussed the role and composition of the Senate at length. There is no doubt that this institution was a fundamental component of the federal compromise in 1867. In fact, the Constitution Act, 1867 contains no less than 15 provisions that are specific to the Senate, including its powers, prerogatives and privileges, composition, appointment of senators and the duration of their tenure of office (essentially sections 21-36), not to mention other provisions in which reference is made to the Senate.

"For Sir John A. Macdonald, there was no question of senators being elected. He disliked the fact that the members of the Legislative Council of the parliament of the province of Canada had been so elected for renewable mandates of eight years."

The Quebec Court of Appeal Senate Reference reviewed the representation by population approach adopted in 1867 for the House of Commons and the character of the Senate as a body that would protect regional and linguistic interests. It described the function of the Senate:

"Historians recognize that for the fathers of confederation, the Senate would have the following functions:

- Regional representation (three then four regions);

- Representation of Quebec's Anglophone minority;

- Sober second thought for bills and amendments to them;

- Providing oversight to those who were wealthy, including the

possibility of controlling any excesses of elected officials.

"Over time, the Senate also became the legislative chamber for the introduction of certain kinds of legislation by the government; particularly laws such as those that were technical or uncontroversial (of which omnibus bills would be an example) apart from money bills.

"In the same manner, as members of parliament, senators could influence a multitude of ministerial or cabinet decisions, especially if they formed part of the government caucus.

"In fact, it seems that the Senate and its members play a significant role in federal political life, and that the institution is not simply a mirror of the House of Commons."

The Quebec Court of Appeal reviewed the mechanisms proposed in Bill C-7 and drew the following conclusion:

"On the whole, when the real meaning and true character of Bill C-7 is analyzed, it unquestionably constituted an attempt to significantly amend the current method of selecting senators, that is, an appointive process until 75, the age of retirement. Such an amendment could only have been implemented as the result of the federal-provincial consensus paragraph 42(1)(b) of the Constitution Act, 1982 contemplates.

"The agreement of a majority of the provinces based on the 7/50 formula would therefore have been required.

"Moreover, it would have been aberrant to impose Bill C-7 on the provinces when it required the holding of elections conducted in accordance with provincial laws, with independent candidates or those endorsed by provincial political parties, without having discussed it with them and in the absence of a consensus that the 7/50 formula affords them.

"Finally, Bill C-7 would be unconstitutional in that it

permitted the amendment of the method of selection of senators as

the provinces may choose at the choice of the province concerned,

which, in 1982, the framers sought to prevent by specifying in

subsection 42(2) of the Constitution

Act, 1982 that an amendment

adopted relative to a matter contained in subsection 42(1)

applies throughout Canada, without any possibility of exclusion.

The framers intended that amendments made with respect to the

matters mentioned in paragraph 42(1)(b) be uniform and ones of

general application."

The Supreme Court of Canada provided a similar contextual framework, describing it as a brief outline of "the institution at the heart of this reference."

"The framers of the Constitution Act, 1867 sought to adapt the British form of government to a new country, in order to have a 'Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.' They wanted to preserve the British structure of a lower legislative chamber composed of elected representatives, an upper legislative chamber made up of elites appointed by the Crown, and the Crown as head of state.

"The upper legislative chamber, which the framers named the Senate, was modeled on the British House of Lords, but adapted to Canadian realities. As in the United Kingdom, it was intended to provide 'sober second thought' on the legislation adopted by the popular representatives in the House of Commons. However, it played the additional role of providing a distinct form of representation for the regions that had joined Confederation and ceded a significant portion of their legislative powers to the new federal Parliament. While representation in the House of Commons was proportional to the population of the new Canadian provinces, each region was provided equal representation in the Senate irrespective of population. This was intended to assure the regions that their voices would continue to be heard in the legislative process even though they might become minorities within the overall population of Canada.

"Over time, the Senate also came to represent various groups that were under-represented in the House of Commons. It served as a forum for ethnic, gender, religious, linguistic, and Aboriginal groups that did not always have a meaningful opportunity to present their views through the popular democratic process.

"Although the product of consensus, the Senate rapidly attracted criticism and reform proposals. Some felt that it failed to provide 'sober second thought' and reflected the same partisan spirit as the House of Commons. Others criticized it for failing to provide meaningful representation of the interests of the provinces as originally intended, and contended that it lacked democratic legitimacy.

"In the years immediately preceding patriation of the Constitution, proposals for reform focused mainly on three aspects: (i) modifying the distribution of seats in the Senate; (ii) circumscribing the powers of the Senate; and (iii) changing the way in which Senators are selected for appointment. These proposals assumed the continued existence of an upper chamber, but sought to improve its contribution to the legislative process.

"In 1978, the federal government tabled a bill to comprehensively reform the Senate by readjusting the distribution of seats between the regions; removing the Senate's absolute veto over most legislation and replacing it with an ability to delay the adoption of legislation; and giving the House of Commons and the provincial legislatures the power to select Senators. The bill was not adopted and, in 1980, this Court concluded that Parliament did not have the power under the Constitution as it then stood to unilaterally modify the fundamental features of the Senate or to abolish it.

"Despite ongoing criticism and failed attempts at reform, the Senate has remained largely unchanged since its creation. The question before us now is not whether the Senate should be reformed or what reforms would be preferable, but rather how the specific changes set out in the Reference can be accomplished under the Constitution. This brings us to the issue of constitutional amendment in Canada."

In its abbreviated reasons for why Senate reform can only be brought about through the general amending formula of the Constitution, the Supreme Court provided a brief description of the amending formulae and the logic and context which should inform their interpretation:

"The Senate is one of Canada's foundational political institutions. It lies at the heart of the agreements that gave birth to the Canadian federation. Despite ongoing criticism and failed attempts at reform, the Senate has remained largely unchanged since its creation. The statute that created the Senate -- the Constitution Act, 1867 -- forms part of the Constitution of Canada and can only be amended in accordance with the Constitution's procedures for amendment (s. 52(2) and (3), Constitution Act, 1982). The concept of an 'amendment to the Constitution of Canada', within the meaning of Part V of the Constitution Act, 1982, is informed by the nature of the Constitution, its underlying principles and its rules of interpretation. The Constitution should not be viewed as a mere collection of discrete textual provisions. It has an architecture, a basic structure. By extension, amendments to the Constitution are not confined to textual changes. They include changes to the Constitution's architecture, that modify the meaning of the constitutional text.

"Part V reflects the political consensus that the provinces must have a say in constitutional changes that engage their interests. It contains four categories of amending procedures. The first is the general amending procedure -- the '7/50' procedure -- (s. 38, complemented by s. 42), which requires a substantial degree of consensus between Parliament and the provincial legislatures. The second is the unanimous consent procedure (s. 41), which applies to certain changes deemed fundamental by the framers of the Constitution Act, 1982. The third is the special arrangements procedure (s. 43), which applies to amendments in relation to provisions of the Constitution that apply to some, but not all, of the provinces. The fourth is made up of the unilateral federal and provincial procedures, which allow unilateral amendment of aspects of government institutions that engage purely federal or provincial interests (ss. 44 and 45)."

Aside from the summary explanation, the Supreme Court reviewed the amending procedures as set out in Part V of the Constitution in detail, pointing out that changes to the Senate can only be amended in accordance with it, arguing that the very "concept of constitutional amendment" had to also be examined.

The Supreme Court described the Constitution as a "a comprehensive set of rules and principles" that provides "an exhaustive legal framework for our system of government," referencing the Supreme Court Secession Reference. The Constitution, it wrote: "defines the powers of the constituent elements of Canada's system of government -- the executive, the legislatures, and the courts -- as well as the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments." In addition, "it governs the state's relationship with the individual. Governmental power cannot lawfully be exercised, unless it conforms to the Constitution."

Further to this, it pointed out that judicial interpretations of the Constitution, "must be informed by the foundational principles of the Constitution, which include principles such as federalism, democracy, the protection of minorities, as well as constitutionalism and the rule of law."

It stated: "These rules and principles of interpretation have led this Court to conclude that the Constitution should be viewed as having an 'internal architecture,' or 'basic constitutional structure.' The notion of architecture expresses the principle that '[t]he individual elements of the Constitution are linked to the others, and must be interpreted by reference to the structure of the Constitution as a whole.' In other words, the Constitution must be interpreted with a view to discerning the structure of government that it seeks to implement. The assumptions that underlie the text and the manner in which the constitutional provisions are intended to interact with one another must inform our interpretation, understanding, and application of the text."

The Supreme Court Reference presents a review of the Part V amending procedures, pointing out that they state "what changes Parliament and the provincial legislatures can make unilaterally, what changes require substantial federal and provincial consent, and what changes require unanimous agreement." It also reviewed the history of the amending formula, noting that it "reflects the principle that constitutional change that engages provincial interests requires both the consent of Parliament and a significant degree of provincial consent."

It wrote that even prior to the patriation of the Constitution, when constitutional amendments required the adoption of a law by the British Parliament, the practice had been established that the federal government consulted with the provinces. "By the time of patriation," it wrote, "this practice had ripened into a constitutional convention requiring substantial consent to constitutional change directly affecting federal-provincial relations."

The Supreme Court notes that the political consensus established in Canada, according to which the provinces must have a say in constitutional changes that engage their interests has the underlying purpose "to constrain unilateral federal powers to effect constitutional change" and the "consecration" of the principal of "the constitutional equality of provinces as equal partners in Confederation," to "foster dialogue between the federal government and the provinces on matters of constitutional change," and "to protect Canada's constitutional status quo until such time as reforms are agreed upon."

[...]

"By requiring significant provincial consensus while stopping short of unanimity, s. 38 'achieves a compromise between the demands of legitimacy and flexibility.' Its 'underlying purpose . . . is to protect the provinces from having their rights or privileges negatively affected without their consent.'"

The Supreme Court concludes that the Section 38 procedures should be accepted as the appropriate method for most constitutional amendments and others should be viewed "as exceptions to the general rule."

Supreme Court Answers Harper Government's Reference Questions

Question 1: Senatorial Tenure

"In relation to each of the following proposed limits to the tenure of Senators, is it within the legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada, acting pursuant to section 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982, to make amendments to section 29 of the Constitution Act, 1867 providing for (a) a fixed term of nine years for Senators, as set out in clause 5 of Bill C-7, the Senate Reform Act; (b) a fixed term of ten years or more for Senators; (c) a fixed term of eight years or less for Senators; (d) a fixed term of the life of two or three Parliaments for Senators; (e) a renewable term for Senators, as set out in clause 2 of Bill S-4, Constitution Act, 2006 (Senate tenure); (f) limits to the terms for Senators appointed after October 14, 2008 as set out in subclause 4(1) of Bill C-7, the Senate Reform Act; and (g) retrospective limits to the terms for Senators appointed before October 14, 2008?"

The Supreme Court answered: No. The Supreme Court points out that changing the duration of senatorial terms requires a constitutional amendment beyond the scope of unilateral federal powers embodied in Section 42 of the Constitution. It wrote:

"The unilateral federal amendment procedure is limited. It is not a broad procedure that encompasses all constitutional changes to the Senate which are not expressly included within another procedure in Part V. [...] Changes that engage the interests of the provinces in the Senate as an institution forming an integral part of the federal system can only be achieved under the general amending procedure. [...]

"The imposition of fixed terms for Senators engages the interests of the provinces by changing the fundamental nature or role of the Senate. Senators are appointed roughly for the duration of their active professional lives. This security of tenure is intended to allow Senators to function with independence in conducting legislative review. The imposition of fixed senatorial terms is a significant change to senatorial tenure. Fixed terms provide a weaker security of tenure. They imply a finite time in office and necessarily offer a lesser degree of protection from the potential consequences of freely speaking one's mind on the legislative proposals of the House of Commons. The imposition of fixed terms, even lengthy ones, constitutes a change that engages the interests of the provinces as stakeholders in Canada's constitutional design and falls within the rule of general application for constitutional change -- the 7/50 procedure in s. 38."

The Supreme Court further elaborated its consideration of the arguments presented by the government:

"The Attorney General of Canada argues that changes to senatorial tenure fall residually within the unilateral federal power of amendment in s. 44 [of the Constitution Act, 1982], since they are not expressly captured by the language of s. 42. He also contends that the imposition of the fixed terms contemplated in the Reference would constitute a minor change that does not engage the interests of the provinces, because those terms are equivalent in duration to the average length of the terms historically served by Senators.

"In essence, the Attorney General of Canada proposes a narrow textual approach to this issue. Section 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982 provides: 'Subject to sections 41 and 42, Parliament may exclusively make laws amending the Constitution of Canada in relation to [...] the Senate [...]' Neither s. 41 nor s. 42 expressly applies to amendments in relation to senatorial tenure. It follows, in his view, that the proposed changes to senatorial tenure are captured by the otherwise unlimited power in s. 44 to make amendments in relation to the Senate."

The Supreme Court states that while Section 42 does not specifically encompass changes to senatorial terms, it does not follow that all changes to the Senate that are not included in Section 42 become subject to the unilateral federal amending procedure.

It writes:

"We are unable to agree with the Attorney General of Canada's interpretation of the scope of s. 44. As discussed, the unilateral federal amendment procedure is limited. It is not a broad procedure that encompasses all constitutional changes to the Senate which are not expressly included within another procedure in Part V. The history, language, and structure of Part V indicate that s. 38, rather than s. 44, is the general procedure for constitutional amendment. Changes that engage the interests of the provinces in the Senate as an institution forming an integral part of the federal system can only be achieved under the general amending procedure. Section 44, as an exception to the general procedure, encompasses measures that maintain or change the Senate without altering its fundamental nature and role.

The Supreme Court argued: "The Senate is a core component of the Canadian federal structure of government. As such, changes that affect its fundamental nature and role engage the interests of the stakeholders in our constitutional design -- i.e. the federal government and the provinces -- and cannot be achieved by Parliament acting alone.

"The question is thus whether the imposition of fixed terms for Senators engages the interests of the provinces by changing the fundamental nature or role of the Senate. If so, the imposition of fixed terms can only be achieved under the general amending procedure. In our view, this question must be answered in the affirmative.

"As discussed above, the Senate's fundamental nature and role is that of a complementary legislative body of sober second thought. The current duration of senatorial terms is directly linked to this conception of the Senate. Senators are appointed roughly for the duration of their active professional lives. This security of tenure is intended to allow Senators to function with independence in conducting legislative review. This Court stated in the Upper House Reference that, '[a]t some point, a reduction of the term of office might impair the functioning of the Senate in providing what Sir John A. Macdonald described as 'the sober second thought in legislation.'' A significant change to senatorial tenure would thus affect the Senate's fundamental nature and role. It could only be achieved under the general amending procedure and falls outside the scope of the unilateral federal amending procedure.

"The imposition of fixed senatorial terms is a significant change to senatorial tenure. We are not persuaded by the argument that the fixed terms contemplated in the Reference are a minor change because they are equivalent in duration to the average term historically served by Senators. Rather, we agree with the submission of the amici curiae that there is an important 'qualitative difference' between tenure for the rough duration of a Senator's active professional life and tenure for a fixed term. Fixed terms provide a weaker security of tenure. They imply a finite time in office and necessarily offer a lesser degree of protection from the potential consequences of freely speaking one's mind on the legislative proposals of the House of Commons."

The Supreme Court further argued that even if a fixed-term could be established so that it was lengthy enough to be functionally equivalent to life tenure and the security that comes with it, it would significantly remain a constitutional change that "engages the interests of the provinces as stakeholders in Canada's constitutional design and falls within the rule of general application for constitutional change -- the 7/50 procedure in s. 38."

Questions 2 and 3: Consultative Elections

"Is it within the legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada, acting pursuant to section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, or section 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982, to enact legislation that provides a means of consulting the population of each province and territory as to its preferences for potential nominees for appointment to the Senate pursuant to a national process as was set out in Bill C-20, the Senate Appointment Consultations Act?" and "Is it within the legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada, acting pursuant to section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, or section 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982, to establish a framework setting out a basis for provincial and territorial legislatures to enact legislation to consult their population as to their preferences for potential nominees for appointment to the Senate as set out in the schedule to Bill C-7, the Senate Reform Act?"

The Supreme Court answered: No.

"Introducing a process of consultative elections for the nomination of Senators would change our Constitution's architecture, by endowing Senators with a popular mandate which is inconsistent with the Senate's fundamental nature and role as a complementary legislative chamber of sober second thought. The view that the consultative election proposals would amend the Constitution of Canada is supported by the language of Part V of the Constitution Act, 1982. The words employed in Part V are guides to identifying the aspects of our system of government that form part of the protected content of the Constitution. Section 42(1)(b) provides that the general amending procedure (s. 38(1)) applies to constitutional amendments in relation to 'the method of selecting Senators.' This broad wording includes more than the formal appointment of Senators by the Governor General and covers the implementation of consultative elections. By employing this language, the framers of the Constitution Act, 1982 extended the constitutional protection provided by the general amending procedure to the entire process by which Senators are 'selected.' Consequently, the implementation of consultative elections falls within the scope of s. 42(1)(b) and is subject to the general amending procedure, without the provincial right to 'opt out.' It cannot be achieved under the unilateral federal amending procedure. Section 44 is expressly made 'subject to' s. 42 -- the categories of amendment captured by s. 42 are removed from the scope of s. 44."

The Supreme Court summarized the arguments of the Harper government concerning consultative elections for Senate appointments as follows:

"The Attorney General of Canada (supported by the attorneys general of Saskatchewan and Alberta as well as one of the amici curiae) submits that implementing consultative elections for Senators does not constitute an amendment to the Constitution of Canada. He argues that this reform would not change the text of the Constitution Act, 1867, nor the means of selecting Senators. He points out that the formal mechanism for appointing Senators -- summons by the Governor General acting on the advice of the Prime Minister -- would remain untouched. Alternatively, he submits that if introducing consultative elections constitutes an amendment to the Constitution, then it can be achieved unilaterally by Parliament under s. 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982."

In response to these arguments, the Supreme Court wrote:

"In our view, the argument that introducing consultative elections does not constitute an amendment to the Constitution privileges form over substance. It reduces the notion of constitutional amendment to a matter of whether or not the letter of the constitutional text is modified. This narrow approach is inconsistent with the broad and purposive manner in which the Constitution is understood and interpreted, as discussed above. While the provisions regarding the appointment of Senators would remain textually untouched, the Senate's fundamental nature and role as a complementary legislative body of sober second thought would be significantly altered.

"We conclude that each of the proposed consultative elections would constitute an amendment to the Constitution of Canada and require substantial provincial consent under the general amending procedure, without the provincial right to 'opt out' of the amendment (s. 42). We reach this conclusion for three reasons: (1) the proposed consultative elections would fundamentally alter the architecture of the Constitution; (2) the text of Part V expressly makes the general amending procedure applicable to a change of this nature; and (3) the proposed change is beyond the scope of the unilateral federal amending procedure (s. 44)."

The Supreme Court explained why elections for the Senate, even consultative, would fundamentally alter the architecture of the Constitution.

"The implementation of consultative elections would amend the Constitution of Canada by fundamentally altering its architecture. It would modify the Senate's role within our constitutional structure as a complementary legislative body of sober second thought.

"The Constitution Act, 1867 contemplates a specific structure for the federal Parliament, 'similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.' The Act creates both a lower elected and an upper appointed legislative chamber (s. 17). It expressly provides that the members of the lower chamber -- the House of Commons -- 'shall be elected' by the population of the various provinces (s. 37). By contrast, it provides that Senators shall be 'summoned' (i.e. appointed) by the Governor General (ss. 24 and 32).

"The contrast between election for members of the House of Commons and executive appointment for Senators is not an accident of history. The framers of the Constitution Act, 1867 deliberately chose executive appointment of Senators in order to allow the Senate to play the specific role of a complementary legislative body of 'sober second thought'.

"As this Court wrote in the Upper House Reference, '[i]n creating the Senate in the manner provided in the Act, it is clear that the intention was to make the Senate a thoroughly independent body which could canvass dispassionately the measures of the House of Commons' (emphasis added). The framers sought to endow the Senate with independence from the electoral process to which members of the House of Commons were subject, in order to remove Senators from a partisan political arena that required unremitting consideration of short-term political objectives.

"Correlatively, the choice of executive appointment for

Senators was also intended to ensure that the Senate would be a complementary

legislative body, rather than a perennial rival of

the House of Commons in the legislative process. Appointed

Senators would not have a popular mandate -- they would not have

the expectations and legitimacy that stem from popular election.

This would ensure that they would confine themselves to their

role as a body mainly conducting legislative review, rather than

as a coequal of the House of Commons. As John A. Macdonald put it

during the Parliamentary debates regarding Confederation,

'[t]here is [...] a greater danger of an irreconcilable

difference of opinion between the two branches of the

legislature, if the upper be elective, than if it holds its

commission from the Crown.' An appointed Senate would be a body

'calmly considering the legislation initiated by the popular

branch, and preventing any hasty or ill considered legislation

which may come from that body, but it will never set itself in

opposition against the deliberate and understood wishes of the

people' (emphasis added).

"The appointed status of Senators, with its attendant assumption that appointment would prevent Senators from overstepping their role as a complementary legislative body, shapes the architecture of the Constitution Act, 1867. It explains why the framers did not deem it necessary to textually specify how the powers of the Senate relate to those of the House of Commons or how to resolve a deadlock between the two chambers. [...]

"The proposed consultative elections would fundamentally modify the constitutional architecture we have just described and, by extension, would constitute an amendment to the Constitution. They would weaken the Senate's role of sober second thought and would give it the democratic legitimacy to systematically block the House of Commons, contrary to its constitutional design.

"Federal legislation providing for the consultative election of Senators would have the practical effect of subjecting Senators to the political pressures of the electoral process and of endowing them with a popular mandate. Senators selected from among the listed nominees would become popular representatives. They would have won a 'true electoral contest' (Quebec Senate Reference, at para. 71), during which they would presumably have laid out a campaign platform and made electoral promises. They would join the Senate after acquiring the mandate and legitimacy that flow from popular election.

"The Attorney General of Canada counters that this broad structural change would not occur because the Prime Minister would retain the ability to ignore the results of the consultative elections and to name whomever he or she wishes to the Senate. We cannot accept this argument. Bills C-20 and C-7 are designed to result in the appointment to the Senate of nominees selected by the population of the provinces and territories. Bill C-7 is the more explicit of the two bills, as it provides that the Prime Minister 'must' consider the names on the lists of elected candidates. It is true that, in theory, prime ministers could ignore the election results and rarely, or indeed never, recommend to the Governor General the winners of the consultative elections. However, the purpose of the bills is clear: to bring about a Senate with a popular mandate. We cannot assume that future prime ministers will defeat this purpose by ignoring the results of costly and hard-fought consultative elections. A legal analysis of the constitutional nature and effects of proposed legislation cannot be premised on the assumption that the legislation will fail to bring about the changes it seeks to achieve.

"In summary, the consultative election proposals set out in the Reference questions would amend the Constitution of Canada by changing the Senate's role within our constitutional structure from a complementary legislative body of sober second thought to a legislative body endowed with a popular mandate and democratic legitimacy."

Question 4: Property Qualifications

"Is it within the legislative authority of the Parliament of Canada, acting pursuant to section 44 of the Constitution Act, 1982, to repeal subsections 23(3) and (4) of the Constitution Act, 1867 regarding property qualifications for Senators?"

The Supreme Court answered yes and no. It said that the Parliament could repeal the requirement that a Senator have net worth of at least $4,000 (subsection 23(4),) but could not do the same in the case of subsection 23(3) which requires a Senator to own real estate worth $4,000 in the province for which they are appointed, stating that this would require a resolution of the legislative assembly of Quebec. The Supreme Court wrote:

"The requirement that Senators have a personal net worth of at least $4,000 (s. 23(4), Constitution Act, 1867) can be repealed by Parliament under the unilateral federal amending procedure. It is precisely the type of amendment that the framers of the Constitution Act, 1982 intended to capture under s. 44. It updates the constitutional framework relating to the Senate without affecting the institution's fundamental nature and role. Similarly, the removal of the real property requirement that Senators own land worth at least $4,000 in the province for which they are appointed (s. 23(3), Constitution Act, 1867) would not alter the fundamental nature and role of the Senate. However, a full repeal of s. 23(3) would render inoperative the option in s. 23(6) for Quebec Senators to fulfill their real property qualification in their respective electoral divisions, effectively making it mandatory for them to reside in the electoral divisions for which they are appointed. It would constitute an amendment in relation to s. 23(6), which contains a special arrangement applicable to a single province, and consequently would fall within the scope of the special arrangement procedure. The consent of Quebec's National Assembly is required pursuant to s. 43 of the Constitution Act, 1982."

Questions 5 and 6: Abolition of the Senate

Question 5: "Can an amendment to the Constitution of

Canada to abolish the Senate be accomplished by the general

amending procedure set out in section 38 of the Constitution Act,

1982, by one of the following methods: (a) by inserting a

separate provision stating that the Senate is to be abolished as

of a certain date, as an amendment to the Constitution Act, 1867

or as a separate provision that is outside of the Constitution

Acts, 1867 to 1982 but that is still part of the Constitution of

Canada; (b) by amending or repealing some or all of the

references to the Senate in the Constitution of Canada; or (c) by

abolishing the powers of the Senate and eliminating the

representation of provinces pursuant to paragraphs 42(1)(b) and

(c) of the Constitution Act, 1982?" and;

Question 6: "If the general amending procedure set out in section 38 of the Constitution Act, 1982 is not sufficient to abolish the Senate, does the unanimous consent procedure set out in section 41 of the Constitution Act, 1982 apply?"

The Supreme Court answered:

"Abolition of the Senate is not merely a matter relating to its 'powers' or its 'members' under s. 42(1)(b) and (c) of the Constitution Act, 1982. This provision captures Senate reform, which implies the continued existence of the Senate. Outright abolition falls beyond its scope. To interpret s. 42 as embracing Senate abolition would depart from the ordinary meaning of its language and is not supported by the historical record. The mention of amendments in relation to the powers of the Senate and the number of Senators for each province presupposes the continuing existence of a Senate and makes no room for an indirect abolition of the Senate. Within the scope of s. 42, it is possible to make significant changes to the powers of the Senate and the number of Senators. But it is outside the scope of s. 42 to altogether strip the Senate of its powers and reduce the number of Senators to zero. The abolition of the upper chamber would entail a significant structural modification of Part V. Amendments to the Constitution of Canada are subject to review by the Senate. The Senate can veto amendments brought under s. 44 and can delay the adoption of amendments made pursuant to ss. 38, 41, 42, and 43 by up to 180 days. The elimination of bicameralism would render this mechanism of review inoperative and effectively change the dynamics of the constitutional amendment process. The constitutional structure of Part V as a whole would be fundamentally altered. Abolition of the Senate would therefore fundamentally alter our constitutional architecture -- by removing the bicameral form of government that gives shape to the Constitution Act, 1867 -- and would amend Part V, which requires the unanimous consent of Parliament and the provinces under s. 41(e) of the Constitution Act, 1982."

In elaborating its reasons for this conclusion, the Supreme Court wrote:

"The Attorney General of Canada argues that the general amending procedure applies because abolition of the Senate falls under matters which Part V expressly says attract that procedure -- amendments in relation to 'the powers of the Senate' and 'the number of members by which a province is entitled to be represented in the Senate' (s. 42(1)(b) and (c)). Abolition, it is argued, is simply a matter of 'powers' and 'members': it literally takes away all of the Senate's powers and all of its members. Alternatively, the Attorney General of Canada argues that since abolition of the Senate is not expressly mentioned anywhere in Part V, it falls residually under the general amending procedure."

"We cannot accept the Attorney General's arguments. Abolition of the Senate is not merely a matter of 'powers' or 'members' under s. 42(1)(b) and (c) of the Constitution Act, 1982. Rather, abolition of the Senate would fundamentally alter our constitutional architecture -- by removing the bicameral form of government that gives shape to the Constitution Act, 1867 -- and would amend Part V, which requires the unanimous consent of Parliament and the provinces (s. 41(e), Constitution Act, 1982).

"It is argued that s. 42(1)(b) and (c), which expressly make the general amending procedure applicable to changes to the 'powers' of the Senate and to the 'number' of Senators allotted to each province, brings abolition of the Senate within the scope of the general amending procedure.

"We cannot accept this argument. It misunderstands the purpose of the express mention of the Senate in s. 42(1)(b) and (c). This provision captures Senate reform, which implies the continued existence of the Senate. Outright abolition falls beyond its scope.

"As discussed above, the references to the Senate in s. 42 were made in anticipation of future Senate reform. The Quebec Court of Appeal aptly captured this historical context and its relevance in interpreting s. 42:

"'The interpretation of section 42 must also take account, in particular, that because of the inability of the federal government and the provinces to agree in 1982 on a total reform of the Constitution, including the Senate, amongst other institutions, the framers decided to postpone further discussion of the matters it contains, while specifying the applicable amending procedure to incorporate an eventual consensus in the Constitution.' (Quebec Senate Reference, at para. 40)

"Abolition of the Senate was not on the minds of the framers of the Constitution Act, 1982. Rather, they turned their minds to the main aspects of Senate reform that were discussed in the years prior to patriation: the distribution of seats in the Senate, the powers of the Senate, and the manner of selecting Senators. They expected ongoing discussion of these aspects of Senate reform and made it clear, through their choice of words in s. 42, that these reforms would require a substantial degree of federal-provincial consensus. However, they assumed that the evolution of Canada's system of government would be characterized by a degree of continuity -- that constitutional change would be incremental and that some core institutions would remain firmly anchored in our constitutional order.

"To interpret s. 42 as embracing Senate abolition would depart from the ordinary meaning of its language and is not supported by the historical record. The mention of amendments in relation to the powers of the Senate and the number of Senators for each province presupposes the continuing existence of a Senate and makes no room for an indirect abolition of the Senate. Within the scope of s. 42, it is possible to make significant changes to the powers of the Senate and the number of Senators. But it is outside the scope of s. 42 to altogether strip the Senate of its powers and reduce the number of Senators to zero.

"The Attorney General of Canada argues that Senate abolition can be accomplished without amending Part V and that it therefore does not fall within the scope of s. 41(e), which requires unanimous federal-provincial consent for amendments to Part V. He argues that the Senate can be abolished without textually modifying the provisions of Part V. The references to the Senate in Part V would simply be viewed as 'spent' and as devoid of legal effect.

"The Attorney General further submits that the Part V amending procedures would remain functional despite the presence of these 'spent' provisions, since the Senate's failure to adopt a resolution authorizing a constitutional amendment can be overridden after the expiration of a 180-day period: s. 47(1), Constitution Act, 1982. Moreover, he submits that the Senate's role in the unilateral federal amending procedure (s. 44) can be eliminated under the general amending procedure, by changing the definition of Parliament in s. 17 of the Constitution Act, 1867 so as to remove the upper house.

"The Attorney General supplements these submissions with the argument that the effects of Senate abolition on Part V would be merely incidental and that they should not trigger the application of the unanimous consent procedure. In his view, Senate abolition would not be, 'in pith and substance,' an amendment in relation to Part V.

"We disagree with these submissions. Once more, the Attorney General privileges form over substance. Part V is replete with references to the Senate and gives the Senate a role in all of the amending procedures, except for the unilateral provincial procedure. Part V was drafted on the assumption that the federal Parliament would remain bicameral in nature, i.e. that there would continue to be both a lower legislative chamber and a complementary upper chamber. Removal of the upper chamber from our Constitution would alter the structure and functioning of Part V. Consequently, it requires the unanimous consent of Parliament and of all the provinces (s. 41(e)).

"The Attorney General of Canada's argument that the upper chamber could be removed without amending Part V fails to persuade us. As discussed, the notion of an amendment to the Constitution of Canada is not limited to textual modifications -- it also embraces significant structural modifications of the Constitution. The abolition of the upper chamber would entail a significant structural modification of Part V. Amendments to the Constitution of Canada are subject to review by the Senate. The Senate can veto amendments brought under s. 44 and can delay the adoption of amendments made pursuant to ss. 38, 41, 42, and 43 by up to 180 days: s. 47, Constitution Act, 1982. The elimination of bicameralism would render this mechanism of review inoperative and effectively change the dynamics of the constitutional amendment process. The constitutional structure of Part V as a whole would be fundamentally altered.

"The argument that Senate abolition would only have ‘incidental' or secondary effects on Part V also fails to persuade us. The effects of Senate abolition on Part V are direct and substantial. While it is true that the Senate's role in constitutional amendment is not as central as that of the House of Commons or the provincial legislatures, its ability to delay the adoption of constitutional amendments nevertheless provides an additional mechanism to ensure that they are carefully considered. Indeed, the Senate's refusal to authorize an amendment can give the House of Commons pause and draw public attention to amendments.

"Since the effects of Senate abolition on Part V cannot be characterized as incidental, it is not necessary to decide whether there exists a doctrine -- analogous to the 'pith and substance' doctrine, discussed above -- that justifies applying the general amending procedure to a constitutional amendment that has incidental effects on a matter coming within the unanimous consent procedure.

"The review of constitutional amendments by an upper house is an essential component of the Part V amending procedures. The Senate has a role to play in all of the Part V amending procedures, except for the unilateral provincial procedure. The process of constitutional amendment in a unicameral system would be qualitatively different from the current process. There would be one less player in the process, one less mechanism of review. It would be necessary to decide whether the amending procedure can function as currently drafted in a unicameral system, or whether it should be modified to provide for a new mechanism of review that occupies the role formerly played by the upper chamber. These issues relate to the functioning of the constitutional amendment formula and, as such, unanimous consent of Parliament and of all the provinces is required under s. 41(e) of the Constitution Act, 1982. [...]"

Read The Marxist-Leninist Daily

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

As concerns the Senate, Harper refuses to

acknowledge

its role in Canada's parliamentary system. He is actively working to

undermine its

functioning,

while trying to usurp its powers for himself, as final arbiter of

legislation

through appointments and raising doubts about the Senate's legitimacy

in

relation to the House of Commons. This was clearly seen recently when

officials of the Harper government insinuated that the Senate had no

right to

amend the Harper government's anti-union legislation Bill C-377. The

amendments to the bill, essentially gutting the legislation, forced it

back to the

House of Commons for reconsideration, which is perfectly within the

traditional right of the Senate. Generating added fury and cries of

"enemy" by

Harper officials, the Senate amendments passed only because certain

Conservative Senators supported them.

As concerns the Senate, Harper refuses to

acknowledge

its role in Canada's parliamentary system. He is actively working to

undermine its

functioning,

while trying to usurp its powers for himself, as final arbiter of

legislation

through appointments and raising doubts about the Senate's legitimacy

in

relation to the House of Commons. This was clearly seen recently when

officials of the Harper government insinuated that the Senate had no

right to

amend the Harper government's anti-union legislation Bill C-377. The

amendments to the bill, essentially gutting the legislation, forced it

back to the

House of Commons for reconsideration, which is perfectly within the

traditional right of the Senate. Generating added fury and cries of

"enemy" by

Harper officials, the Senate amendments passed only because certain

Conservative Senators supported them.