|

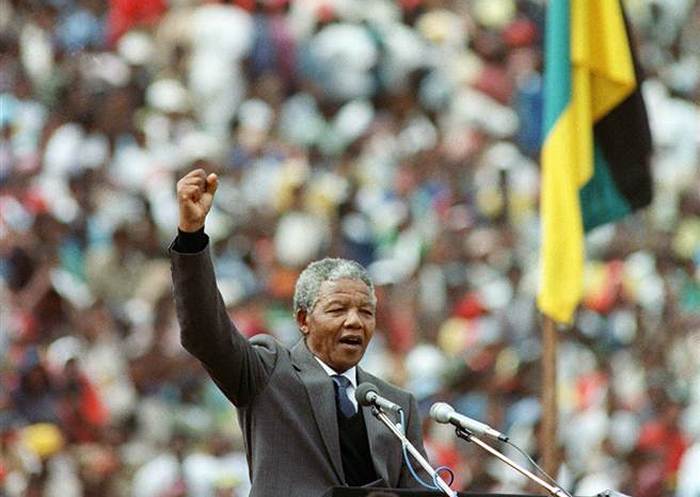

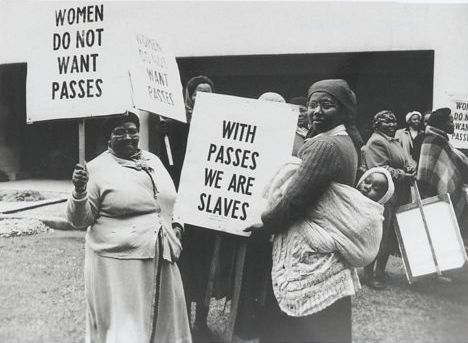

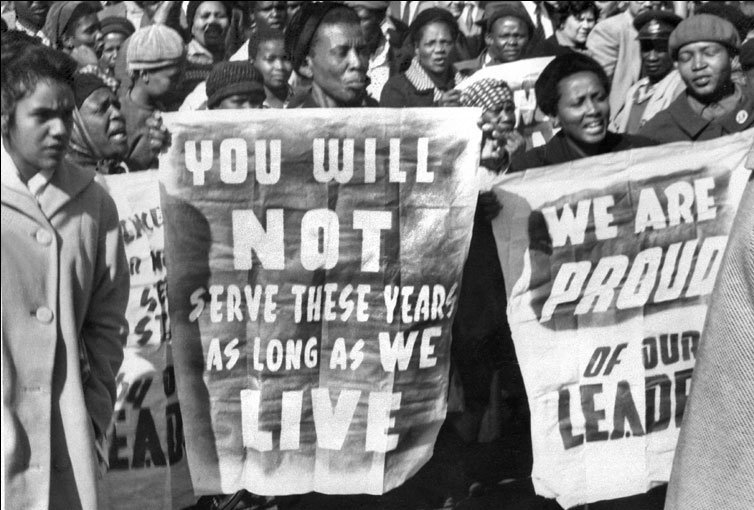

December 7, 2013 - No. 48 Madiba Is Gone; The Struggle Continues Nelson Mandela addresses a jubilant mass rally of 100,000 people in Soweto, February 13, 1990, two days after his release from 27 years of political imprisonment by the racist apartheid regime of South Africa, his freedom the result of sustained political action and armed struggle in South Africa. For Your Information • Biography of Nelson Mandela - Government of South Africa - • We Admire the Achievements of the Cuban Revolution - Speech by Nelson Mandela, Moncada Day Rally, Matanzas, Cuba, July 26, 1991 - Nelson Mandela, 1918-2013 Madiba Is Gone; The Struggle Continues  Left: Historic march by 20,000 women in Pretoria against the racist pass laws, August 9, 1956, today commemorated as Women's Day in South Africa. The women chanted the phrase “wathinth’ abafazi, wathinth’ imbokodo” which translates as “you strike a woman, you strike a rock.” Right: Nelson Mandela burns his passbook. On Thursday evening December 5, Nelson Mandela died at his home in Johannesburg, South Africa. The life of the man known to the anti-apartheid movement as Madiba spanned almost the entire existence of the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC was founded under British colonial rule in January 1912 and it was within it that Madiba would play many leadership roles. The ANC provided the umbrella under which all those opposed to white minority rule, from revolutionary communists to trade union activists to dispossessed township youth, came together and worked out a program of struggle aimed at achieving black majority rule. Mandela was part and parcel of the wave of anti-colonial and national liberation struggles that swept Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean after the Second World War. Facing implacable violence from the apartheid state, the South African liberation movement took up arms after all peaceful means for change had proven fruitless. He was incarcerated at the white-racist apartheid regime's Robben Island military prison for 27 years for the crime of organizing the Umkhonto ne Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation") armed wing of the ANC. He won release as a by-product of the confluence of two powerful currents of struggle at the end of the 1980s.

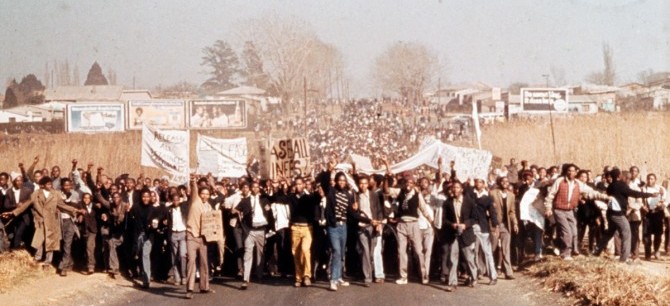

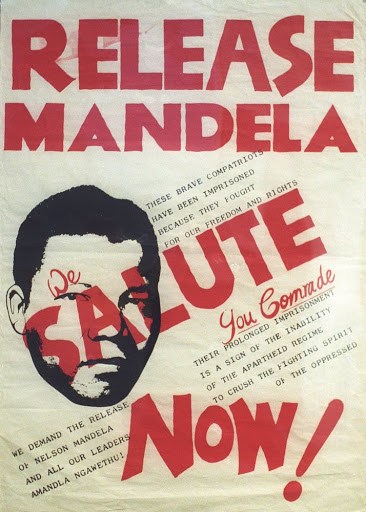

The main current was the anti-apartheid movement's struggle to render the black townships ungovernable at home. On the occasion of reporting his death, the monopoly media once again uniformly dismissed this as little more than terrorism. Indeed, Mandela was condemned as a terrorist by those same powers that now praise him. When Mandela was captured by South African forces on August 5, 1962, the U.S. CIA provided the fascist South African government with the information that led to the capture -- the prelude to his 27-year imprisonment. During the 1980s, the white-minority regime was backed covertly by the government of U.S. President Reagan and openly by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The other current of the struggle for South Africa's liberation was the military struggle by the SWAPO guerrilla fighters in Namibia to end South Africa's illegal occupation of that country, and the fight in Angola by the combined armed forces of Angola and Cuba to end the apartheid regime's war of terrorism against its neighbouring countries -- the "front-line states." The aim of South Africa's terrorist onslaught was to impose its hegemony on the region, forcing the peoples of southern Africa into accepting the permanence of white minority rule. In South Africa, people are acutely aware of the decisive contribution of the Cuban armed forces at the Angolan town of Cuito Cuanavale in finally destroying the myth of the military invincibility of the racist South African armed forces. The monopoly media's coverage of Mandela's passing has conveniently and deliberately ignored Cuba's crucial role in the demise of apartheid. Mandela never forgot. After he was released from prison, one of the first countries outside of Africa and the first country in Latin America that he chose to visit was Cuba. The South African liberation struggle was aided and abetted by a mass international anti-apartheid movement. The demand for Mandela's release stood at the centre of this movement, together with the demand that countries cease to engage economically with the racist regime. This movement was both driven by the world's revulsion at the repugnant apartheid system and inspired by the courageous struggle of South Africans, epitomized by the figure of Mandela.  The notorious police of the apartheid regime carry out the Sharpeville massacre, in which a mass protest against the pass laws was brutally put down and 69 people killed, March 21, 1960.  The famous Soweto uprising of youth and students which began on June 16, 1976, led to a renewed wave of resistance amongst black South Africans. History and the world's people will not soon forget the positive developments of lasting value accomplished for South Africans and the entire African continent with Madiba as the tireless figurehead. Also, the silence of the monopoly media around the mass revolutionary elements and other aspects of the people's victorious struggle will not succeed in their aim of driving today's battles for liberation into blind alleys.

As has already been happening, going forward from today, the fronts of anti-imperialist struggle will continue to further reconstitute themselves for protracted battles against the starkest of dangers, a third world war being prepared by the U.S. imperialists and their tools. As we witness a new scramble for Africa, the imperial powers of the 21st century seek to repeat what the European powers of the 19th century achieved, the carving up of Africa among themselves. This new scramble for Africa, however, is replete with even more serious dangers, as Africa would be transformed into an arena in which the imperialists openly wage the fight against each other and use Africa as a platform for projecting their power on a global scale. In this cauldron Africans will be sacrificed en masse. In this context the anti-imperialist character of the African national liberation struggles of the 20th century cannot be ignored. The shameless efforts of the monopoly media to present the South African black majority's achievement with Madiba at the head as repudiation and rejection of anti-imperialist struggle including all its revolutionary features will not survive scrutiny or repetition much longer. Madiba is gone; the struggle continues. (Photos: ANC Archives, South African History Archives, Mayibuye Archives)

For Your Information Biography of Nelson MandelaEarly Years

Rolihlahla Mandela was born in Mvezo, a village near Mthatha in the Transkei, on July 18, 1918, to Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Henry Mgadla Mandela. His father was the principal councillor to the Acting Paramount Chief of the Thembu royal house. Rolihlahla literally means "pulling the branch of a tree." After his father's death in 1927, the young Rolihlahla became the ward of Jongintaba Dalindyebo, the Paramount Chief, to be groomed to assume high office. Hearing the elder's stories of his ancestor's valour during the wars of resistance, he dreamed also of making his own contribution to the freedom struggle of his people. After receiving a primary education at a local mission school, where he was given the name Nelson, he was sent to the Clarkebury Boarding Institute for his Junior Certificate and then to Healdtown, a Wesleyan secondary school of some repute, where he matriculated. He then enrolled at the University College of Fort Hare for the Bachelor of Arts Degree where he was elected onto the Students' Representative Council. He was suspended from college for joining in a protest boycott, along with Oliver Tambo. He and his cousin Justice ran away to Johannesburg to avoid arranged marriages and for a short period he worked as a mine policeman. Mandela was introduced to Walter Sisulu in 1941 and it was Sisulu who arranged for him to do his articles at Lazar Sidelsky's law firm. Completing his BA through the University of South Africa (Unisa) in 1942, he commenced study for his LLB shortly afterwards (though he left the University of the Witwatersrand without graduating in 1948). He entered politics in earnest while studying, and joined the African National Congress in 1943. Despite his increasing political awareness and activities, Mr Mandela also had time for other things. "It was in the lounge of the Sisulu's home that I met Evelyn Mase She was a quiet, pretty girl from the countryside who did not seem over-awed by the comings and goings .... Within a few months I had asked her to marry me, and she accepted." They married in a civil ceremony at the Native Commissioner's Court in Johannesburg, "for we could not afford a traditional wedding or feast." Evelyn and Nelson went on to have four children: Thembikile (1946), Makaziwe (1947), who died at nine months), Makgatho (1951) and Makaziwe (1954). The couple was divorced in 1958. At the height of the Second World War, in 1944, a small group of young Africans who were members of the African National Congress, banded together under the leadership of Anton Lembede. Among them were William Nkomo, Walter Sisulu, Oliver R Tambo, Ashby P Mda and Nelson Mandela. Starting out with 60 members, all of whom were residing around the Witwatersrand, these young people set themselves the formidable task of transforming the ANC into a more radical mass movement. Their chief contention was that the political tactics of the "old guard" leadership of the ANC, reared in the tradition of constitutionalism and polite petitioning of the government of the day, were proving inadequate to the tasks of national emancipation. In opposition to the old guard, Lembede and his colleagues espoused a radical African nationalism grounded in the principle of national self-determination. In September 1944 they came together to found the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL). Mandela soon impressed his peers by his disciplined work and consistent effort and was elected as the league's National Secretary in 1948. By painstaking work, campaigning at the grass-roots and through its mouthpiece Inyaniso (Truth) the ANCYL was able to canvass support for its policies amongst the ANC membership. Emerging as LeaderSpurred on by the victory of the National Party which won the 1948 all-white elections on the platform of apartheid, at the 1949 Annual Conference the Programme of Action, inspired by the Youth League, which advocated the weapons of boycott, strike, civil disobedience and non-co-operation, was accepted as official ANC policy. The Programme of Action had been drawn up by a sub-committee of the ANCYL composed of David Bopape, Ashby Mda, Nelson Mandela, James Njongwe, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo. To ensure its implementation the membership replaced older leaders with a number of younger men. Dr Walter Sisulu, a founding member of the Youth League, was elected secretary-general. The conservative Dr AB Xuma lost the presidency to Dr JS Moroka, a man with a reputation for greater militancy. In December Mandela himself was elected to the NEC at the National Conference. When the ANC launched its Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws in 1952, Mandela, by then President of the Youth League, was elected National Volunteer-in-Chief. The Defiance Campaign was conceived as a mass civil disobedience campaign that would snowball from a core of selected volunteers to involve more and more ordinary people, culminating in mass defiance. Fulfilling his responsibility as Volunteer-in-Chief,

Mandela travelled the

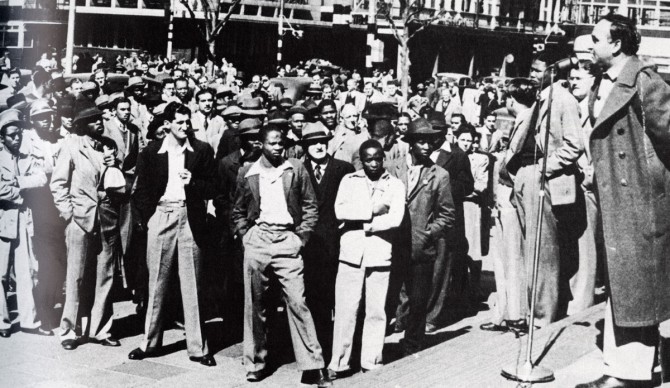

country organising resistance to discriminatory legislation.  Nelson Mandela (second from right) of the ANC Youth League and Dr. Yusuf Dadoo of the Transvaal Indian Congress address a public forum on the steps of Johannesburg City Hall, 1945. Charged, with Moroka, Sisulu and 17 others, and brought to trial for his role in the campaign, the court found that Mandela and his co-accused had consistently advised their followers to adopt a peaceful course of action and to avoid all violence. For his part in the Defiance Campaign, Mandela was convicted of contravening the Suppression of Communism Act and given a suspended prison sentence. Shortly after the campaign ended, he was also prohibited from attending gatherings and confined to Johannesburg for six months. During this period of restrictions, Mandela wrote the attorneys admission examination and was admitted to the profession. He opened a practice in Johannesburg in August 1952, and in December, in partnership with Oliver Tambo, opened South Africa's first black law firm in central Johannesburg. He says of himself during that time: "As an attorney, I could be rather flamboyant in court. I did not act as though I were a black man in a white man's court, but as if everyone else -- white and black -- was a guest in my court. When presenting a case, I often made sweeping gestures and used high-flown language .... (and) used unorthodox tactics with witnesses." Their professional status didn't earn Mandela and Tambo any personal immunity from the brutal apartheid laws. They fell foul of the land segregation legislation, and the authorities demanded that they move their practice from the city to the back of beyond, as Mandela later put it, "miles away from where clients could reach us during working hours. This was tantamount to asking us to abandon our legal practice, to give up the legal service of our people No attorney worth his salt would easily agree to do that." The partnership resolved to defy the law. In 1953 Nelson Mandela was given the responsibility to prepare a plan that would enable the leadership of the movement to maintain dynamic contact with its membership without recourse to public meetings. The objective was to prepare for the possibility that the ANC would, like the Communist Party, be declared illegal and to ensure that the organisation would be able to operate from underground. This was the M-Plan, named after him. "The plan was conceived with the best of intentions but it was instituted with only modest success and its adoption was never widespread." During the early fifties Mandela played an important part in leading the resistance to the Western Areas removals, and to the introduction of Bantu Education. He also played a significant role in popularising the Freedom Charter, adopted by the Congress of the People in 1955. Having been banned again for 2 years in 1953, neither Mandela nor Sisulu were able to attend but "we found a place at the edge of the crowd where we could observe without mixing in or being seen." During the whole of the fifties, Mandela was the victim of various forms of repression. He was banned, arrested and imprisoned. A five year banning order was enforced against him in March 1956. "(But) this time my attitude towards my bans had changed radically. When I was first banned, I abided by the rules and regulations of my persecutors. I had now developed contempt for these restrictions. To allow my activities to be circumscribed (by) my opponent was a form of defeat, and I resolved not to become my own jailer." Although Nelson and Evelyn had effectively separated in 1955, it wasn't until 1958 that they formally divorced -- and shortly afterwards, in June, he was married to Nomzamo Winnie Mandela. Their first date was at an Indian restaurant near Nelson's office and he recalls that she was "dazzling, and even the fact that she had never before tasted curry and drank glass after glass of water to cool her palate only added to her charm .... Winnie has laughingly told people that I never proposed to her, but I always told her that I asked her on our very first date and that I simply took it for granted from that day forward." Unlike his first marriage, the couple observed most of the traditional requirements, including payment of 'lobola', and were married in a local church in Bizana on the 14th of June. There was no time (or money) for a honeymoon -- Nelson had to appear in court for the continuing Treason Trial and anyway his banning order had only been relaxed for 6 days. The Trials Protest against "Treason Trials" of anti-apartheid leaders, December 19, 1956. In fact for much of the latter half of the decade, he was one of the 156 accused in the mammoth Treason Trial, at great cost to his legal practice and his political work, though he recalls that, during his incarceration in the Fort, the communal cell "became a kind of convention for far-flung freedom fighters." After the Sharpeville Massacre on 21st March 1960, the ANC was outlawed, and Mandela, still on trial, was detained, along with hundreds of others. The Treason Trial collapsed in 1961 as South Africa was being steered towards the adoption of the republic constitution. With the ANC now illegal the leadership picked up the threads from its underground headquarters and Nelson Mandela emerged at this time as the leading figure in this new phase of struggle. Under the ANC's inspiration, 1,400 delegates came together at an All-in African Conference in Pietermaritzburg during March 1961. Mandela was the keynote speaker. In an electrifying address he challenged the apartheid regime to convene a national convention, representative of all South Africans to thrash out a new constitution based on democratic principles. Failure to comply, he warned, would compel the majority (Blacks) to observe the forthcoming inauguration of the Republic with a mass general strike. He immediately went underground to lead the campaign. Although fewer answered the call than Mandela had hoped, it attracted considerable support throughout the country. The government responded with the largest military mobilisation since the war, and the Republic was born in an atmosphere of fear and apprehension. Forced to live apart from his family (and he and Winnie by now had 2 daughters, Zenani born in 1959 and Zindzi, born 1960) moving from place to place to evade detection by the government's ubiquitous informers and police spies, Mandela had to adopt a number of disguises. Sometimes dressed as a labourer, at other times as a chauffeur, his successful evasion of the police earned him the title of the Black Pimpernel. He managed to travel around the country and stayed with numerous sympathisers -- a family in Market Street central Johannesburg, in his comrade Wolfie Kodesh's flat (where he insisted on running on-the-spot every day), in the servant's quarters of a doctor's house where he pretended to be a gardener, and on a sugar plantation in Natal.

It was during this time that he, together with other leaders of the ANC, constituted a new section of the liberation movement, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), as an armed nucleus with a view to preparing for armed struggle, with Mandela as its commander in chief. At the Rivonia trial, Mandela explained: "At the beginning of June 1961, after long and anxious assessment of the South African situation, I and some colleagues came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be wrong and unrealistic for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force. It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle, and to form Umkhonto we Sizwe ... the Government had left us no other choice." In 1962 Mandela left the country, as 'David Motsamayi', and travelled abroad for several months. In Ethiopia he addressed the Conference of the Pan African Freedom Movement of East and Central Africa, and was warmly received by senior political leaders in several countries including Tanganyika, Senegal, Ghana and Sierra Leone. He also spent time in London where he managed to find time, with Oliver Tambo, to see the sights as well as to spend time with many exiled comrades. During this trip Mandela met up with the first group of 21 MK recruits on their way to Addis Ababa for guerrilla training. Prisoner 46664

|

Demonstration opposes the guity verdict of the Rivonia Treason Trials against Nelson Mandela and other leaders of the ANC, Pretoria, June 14, 1964. |

The Rivonia Trial, as it came to be known, lasted eight months. Most of the accused stood up well to the prosecution, having made a collective decision that this was a political trial and that they would take the opportunity to make public their political beliefs.

Three of the accused, Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki also decided that, if they were given the death sentence, they would not appeal.

Mandela's statement in court during the trial is a classic in the history of the resistance to apartheid, and has been an inspiration to all who have opposed it. He ended with these words:

"I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die."

All but two of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment on June 12, 1964. The black prisoners were flown secretly to Robben Island immediately the trial was over to begin serving their sentences.

Nelson Mandela's time in prison, which amounted to almost 27 years, was marked by many small and large events which played a crucial part in shaping the personality and attitudes of the man who was to become the first President of a democratic South Africa.

Many fellow prisoners and warders influenced him and he, in his turn, influenced them. While he was in jail his mother and son died, his wife was banned and subjected to continuous arrest and harassment, and the liberation movement was reduced to isolated groups of activists.

In March 1982, after 18 years, he

was suddenly

transferred to Pollsmoor

Prison in Cape Town (with Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba and Andrew

Mlangeni) and in December 1988 he was moved to the Victor Verster

Prison

near Paarl, from where he was eventually released.

In March 1982, after 18 years, he

was suddenly

transferred to Pollsmoor

Prison in Cape Town (with Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba and Andrew

Mlangeni) and in December 1988 he was moved to the Victor Verster

Prison

near Paarl, from where he was eventually released.

While in prison, Mandela flatly rejected offers made by his jailers for remission of sentence in exchange for accepting the bantustan policy by recognising the independence of the Transkei and agreeing to settle there.

Again in the eighties Mandela and others rejected an offer of release on condition that he renounce violence.

Prisoners cannot enter into contracts -- only free men can negotiate, he said.

Nevertheless Mandela did initiate talks with the apartheid regime in 1985, when he wrote to Minister of Justice Kobie Coetsee.

They first met later that year when Mandela was hospitalised for prostate surgery.

Shortly after this he was moved to a single cell at Pollsmoor and this gave Mandela the chance to start a dialogue with the government -- which took the form of 'talks about talks'.

Throughout this process, he was adamant that negotiations could only be carried out by the full ANC leadership. In time, a secret channel of communication would be set up whereby he could get messages to the ANC in Lusaka, but at the beginning he said: "I chose to tell no-one what I was about to do.

There are times when a leader must move out ahead of the flock, go off in a new direction, confident that he is leading his people in the right direction."

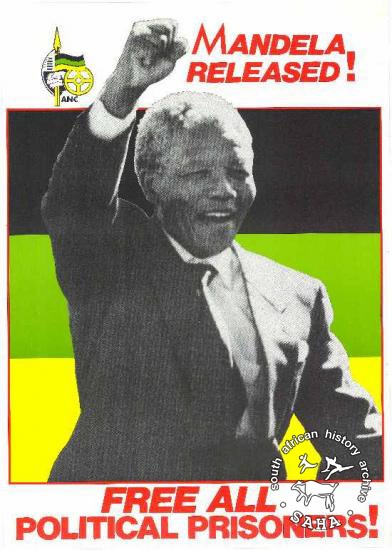

Released on February 11, 1990, Mandela plunged wholeheartedly into his life's work, striving to attain the goals he and others had set out almost four decades earlier.

In 1991, at the first national conference of the ANC held inside South Africa after being banned for decades, Nelson Mandela was elected President of the ANC while his lifelong friend and colleague, Oliver Tambo, became the organisation's National Chairperson.

Negotiating Peace

Election rally for Nelson Mandela, Mmabatho, March 15, 1994.

In a life that symbolises the triumph of the human spirit, Nelson Mandela accepted the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize (along with FW de Klerk) on behalf of all South Africans who suffered and sacrificed so much to bring peace to our land.

The era of apartheid formally came to an end on the April 27, 1994, when Nelson Mandela voted for the first time in his life -- along with his people.

However, long before that date it had become clear, even before the start of negotiations at the World Trade Centre in Kempton Park, that the ANC was increasingly charting the future of South Africa.

Rolihlahla Nelson Dalibunga Mandela was inaugurated as President of a democratic South Africa on May 10, 1994.

In his inauguration speech he said:

"We dedicate this day to all the heroes and heroines in this country and the rest of the world who sacrificed in many ways and surrendered their lives so that we could be free.

"Their dreams have become reality. Freedom is their reward.

"We are both humbled and elevated by the honour and privilege that you, the people of South Africa, have bestowed on us, as the first President of a united, democratic, non-racial and non-sexist government.

"We understand it still that there is no easy road to freedom. We know it well that none of us acting alone can achieve success. We must therefore act together as a united people, for national reconciliation, for nation building, for the birth of a new world. Let there be justice for all.

"Let there be peace for all. Let there be work, bread, water and salt for all. Let each know that for each the body, the mind and the soul have been freed to fulfil themselves.

"Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world. Let freedom reign."

Mandela stepped down in 1999 after one term as President -- but for him there has been no real retirement.

He set up three foundations bearing his name: The Nelson Mandela Foundation, The Nelson Mandela Children's Fund and The Mandela-Rhodes Foundation.

Until very recently his schedule has been relentless. But during this period he has had the love and support of his large family -- including his wife Graça Machel, whom he married on his 80th birthday in 1998.

In April 2007 Mandla Mandela, grandson of Nelson and son of Makgatho Mandela who died in 2005, was installed as head of the Mvezo Traditional Council at an 'ubeko' (anointment) ceremony at the Mvezo Great Place, the seat of the Madiba clan.

Nelson Mandela never wavered in his devotion to democracy, equality and learning.

Despite terrible provocation, he has never answered racism with racism. His life has been an inspiration, in South Africa and throughout the world, to all who are oppressed and deprived, to all who are opposed to oppression and deprivation.

(Photos: ANC Archives)

We Admire the Achievements of the Cuban Revolution

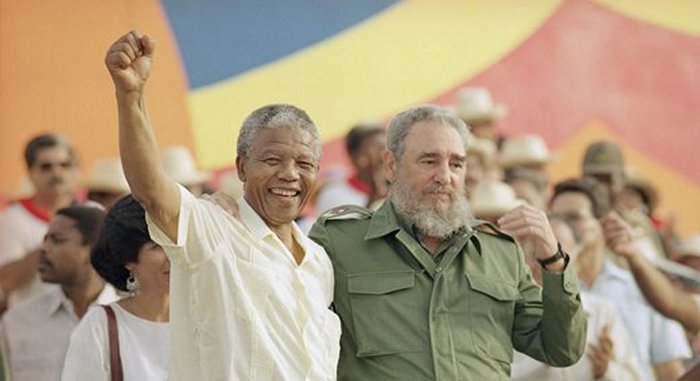

After 27-years of imprisonment by the racist/fascist apartheid system, Nelson Mandela chose Cuba as the first country outside of Africa to visit. During that visit he delivered the following speech outlining Cuba's decisive contribution to the South African liberation struggle.

***

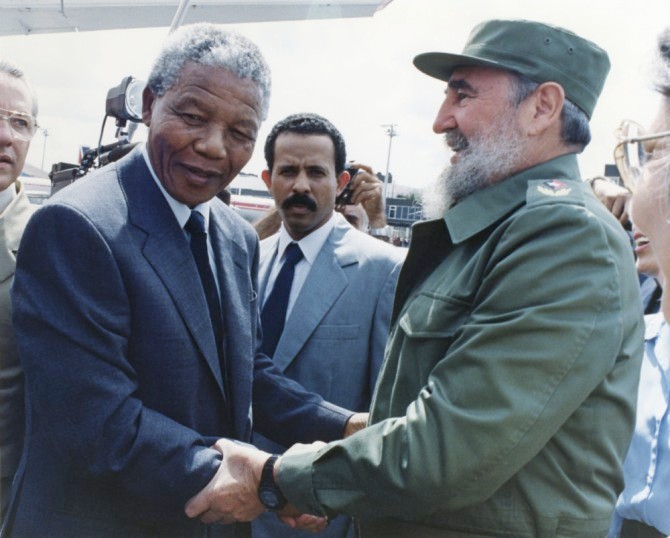

Nelson Mandela makes his historic visit to Cuba in 1991, to pay his respects to President Fidel Castroand the Cuban people for taking up the fight to end the racist apartheid regime as their own and at great sacrifice.

First secretary of the Communist Party, president of the Council of State and of the government of Cuba, president of the socialist republic of Cuba, commander-in-chief, Comrade Fidel Castro;

Cuban internationalists, who have done so much to free our continent; Cuban people; comrades and friends:

It is a great pleasure and honour to be present here today, especially on so important a day in the revolutionary history of the Cuban people. Today Cuba commemorates the thirty- eighth anniversary of the storming of the Moncada. Without Moncada the Granma expedition, the struggle in the Sierra Maestra, the extraordinary victory of January 1, 1959, would never have occurred.

Today this is revolutionary Cuba, internationalist Cuba, the country that has done so much for the peoples of Africa.

We have long wanted to visit your country and express

the many feelings

that we have about the Cuban revolution, about the role of Cuba in

Africa,

southern Africa, and the world.

The Cuban people hold a special place in the hearts of the people of Africa. The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom, and justice, unparalleled for its principled and selfless character.

From its earliest days the Cuban revolution has itself been a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people. We admire the sacrifices of the Cuban people in maintaining their independence and sovereignty in the face of a vicious imperialist-orchestrated campaign to destroy the impressive gains made in the Cuban revolution.

We too want to control our own destiny. We are determined that the people of South Africa will make their future and that they will continue to exercise their full democratic rights after liberation from apartheid. We do not want popular participation to cease at the moment when apartheid goes. We want to have the moment of liberation open the way to ever-deepening democracy.

We admire the achievements of the Cuban revolution in

the sphere of

social welfare. We note the transformation from a country of imposed

backwardness to universal literacy. We acknowledge your advances in the

fields of health, education, and science.

There are many things we learn from your experience. In particular we are moved by your affirmation of the historical connection to the continent and people of Africa.

Your consistent commitment to the systematic eradication of racism is unparalleled.

But the most important lesson that you have for us is

that no matter what

the odds, no matter under what difficulties you have had to struggle,

there can

be no surrender! It is a case of freedom or death!

I know that your country is experiencing many difficulties now, but we have confidence that the resilient people of Cuba will overcome these as they have helped other countries overcome theirs.

We know that the revolutionary spirit of today was started long ago and that its spirit was kindled by many early fighters for Cuban freedom, and indeed for freedom of all suffering under imperialist domination.

We too are also inspired by the life and example of Jose Martí, who is not only a Cuban and Latin American hero but justly honoured by all who struggle to be free.

We also honour the great Che Guevara, whose

revolutionary exploits,

including on our own continent, were too powerful for any prison

censors to

hide from us. The life of Che is an inspiration to all human beings who

cherish freedom. We will always honour his memory.

We come here with great humility. We come here with great emotion. We come here with a sense of a great debt that is owed to the people of Cuba. What other country can point to a record of greater selflessness than Cuba has displayed in its relations with Africa?

How many countries of the world benefit from Cuban health workers or educationists? How many of these are in Africa?

Where is the country that has sought Cuban help and has had it refused?

How many countries under threat from imperialism or

struggling for

national liberation have been able to count on Cuban support?

It was in prison when I first heard of the massive assistance that the Cuban internationalist forces provided to the people of Angola, on such a scale that one hesitated to believe, when the Angolans came under combined attack of South African, CIA-financed FNLA, mercenary, UNITA, and Zairean troops in 1975.

We in Africa are used to being victims of countries wanting to carve up our territory or subvert our sovereignty. It is unparalleled in African history to have another people rise to the defence of one of us.

We know also that this was a popular action in Cuba. We are aware that those who fought and died in Angola were only a small proportion of those who volunteered. For the Cuban people internationalism is not merely a word but something that we have seen practiced to the benefit of large sections of humankind.

We know that the Cuban forces were willing to withdraw shortly after repelling the 1975 invasion, but the continued aggression from Pretoria made this impossible.

Your presence and the reinforcement of your forces in the battle of Cuito Cuanavale was of truly historic significance.

The crushing defeat of the racist army at Cuito Cuanavale was a victory for the whole of Africa!

The overwhelming defeat of the racist army at Cuito Cuanavale provided the possibility for Angola to enjoy peace and consolidate its own sovereignty!

The defeat of the racist army allowed the struggling people of Namibia to finally win their independence!

The decisive defeat of the apartheid aggressors broke the myth of the invincibility of the white oppressors!

The defeat of the apartheid army was an inspiration to the struggling people inside South Africa!

Without the defeat of Cuito Cuanavale our organizations would not have been unbanned!

The defeat of the racist army at Cuito Cuanavale has made it possible for me to be here today!

Cuito Cuanavale was a milestone in the history of the struggle for southern African liberation!

Cuito Cuanavale has been a turning point in the struggle

to free the

continent and our country from the scourge of apartheid!

Opening of the international symposium "Africa's Unknown War: Apartheid Terror, Cuba & Southern Africa Liberation" held in Toronto, September 27 and 28, 2013. At top, Dr. Afua Cooper (JRJ Chair of Black Canadian Studies) performs one of her acclaimed poems. Bottom left: Jorge Risquet, Cuban negotiator in the talks which led to Namibia's independence and accelerated the end of the racist regime in South Africa. Bottom right: H.E. Julio Garmendia (Cuban Ambassador);

Miraly Gonzalez (1st Secretary, Cuban Embassy); H.E. Agostinho Tavares (Angolan Ambassador);

Javier Domokos (Cuban Consul General-Toronto).

Apartheid is not something that started yesterday. The origins of white racist domination go back three and a half centuries to the moment when the first white settlers started a process of disruption and later conquest of the Khoi, San, and other African peoples -- the original inhabitants of our country.

The process of conquest from the very beginning engendered a series of wars of resistance, which in turn gave rise to our struggle for national liberation. Against heavy odds, African peoples tried to hold on to their lands. But the material base and consequent firepower of the colonial aggressors doomed the divided tribal chiefdoms and kingdoms to ultimate defeat.

This tradition of resistance is one that still lives on as an inspiration to our present struggle. We still honour the names of the great prophet and warrior Makana, who died while trying to escape from Robben Island prison in 1819, Hintsa, Sekhukhune, Dingane, Moshoeshoe, Bambatha, and other heroes of the early resistance to colonial conquest.

It was against the background of this land seizure and conquest that the Union of South Africa was created in 1910. Outwardly South Africa became an independent state, but in reality power was handed over by the British conquerors to whites who had settled in the country. They were able in the new Union of South Africa to formalize racial oppression and economic exploitation of blacks.

Following the creation of the Union, the passing of the Land Act,

purporting to legalize the land seizures of the nineteenth century,

gave

impetus to the process leading to the formation of the African National

Congress on January 8, 1912.

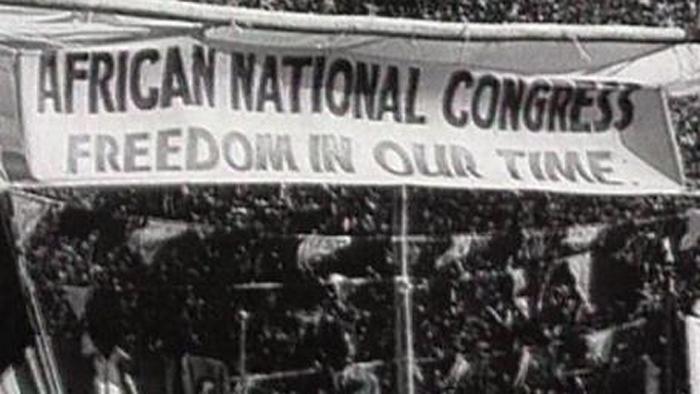

A rally during the early days of the ANC.

I am not going to give you a history of the ANC. Suffice it to say that the last eighty years of our existence has seen the evolution of the ANC from its earliest beginnings aimed at uniting the African peoples, to its becoming the leading force in the struggle of the oppressed masses for an end to racism and the establishment of a non-racial, non-sexist, and democratic state.

Its membership has been transformed from its early days when they were a small group of professionals and chiefs, etc., into a truly mass organization of the people.

Its goals have changed from seeking improvement of the lot of Africans to instead seeking the fundamental transformation of the whole of South Africa into a democratic state for all.

Its methods of achieving its more far-reaching goals have over decades taken on a more mass character, reflecting the increasing involvement of the masses within the ANC and in campaigns led by the ANC.

Sometimes people point to the initial aims of the ANC and its early composition in order to suggest that it was a reformist organization. The truth is that the birth of the ANC carried from the beginning profoundly revolutionary implications.

The formation of the ANC was the first step towards creation of a new South African nation. That conception was developed over time, finding clear expression thirty-six years ago in the Freedom Charter's statement that "South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white." This was an unambiguous rejection of the racist state that had existed and an affirmation of the only alternative that we find acceptable, one where racism and its structures are finally liquidated.

It is well known that the state's response to our legitimate democratic demands was, among other things, to charge our leadership with treason and, in the beginning of the 1960s, to use indiscriminate massacres. That and the banning of our organizations left us with no choice but to do what every self-respecting people, including the Cubans, have done -- that is, to take up arms to win our country back from the racists.

I must say that when we wanted to take up arms we approached numerous Western governments for assistance and we were never able to see any but the most junior ministers. When we visited Cuba we were received by the highest officials and were immediately offered whatever we wanted and needed. That was our earliest experience with Cuban internationalism.

Although we took up arms, that was not our preference. It was the apartheid regime that forced us to take up arms. Our preference has always been for a peaceful resolution of the apartheid conflict.

The combined struggles of our people within the country, as well as the mounting international struggle against apartheid during the 1980s, raised the possibility of a negotiated resolution of the apartheid conflict. The decisive defeat of Cuito Cuanavale altered the balance of forces within the region and substantially reduced the capacity of the Pretoria regime to destabilize its neighbours. This, in combination with our people's struggles within the country, was crucial in bringing Pretoria to realize that it would have to talk.

It was the ANC that initiated the current peace process that we hope will lead to a negotiated transfer of power to the people. We have not initiated this process for goals any different from those when we pursued the armed struggle. Our goals remain achievement of the demands of the Freedom Charter, and we will settle for nothing less than that.

No process of negotiations can succeed until the apartheid regime realizes that there will not be peace unless there is freedom and that we are not going to negotiate away our just demands. They must understand that we will reject any constitutional scheme that aims at continuing white privileges.

There is reason to believe that we have not yet succeeded in bringing this home to the government, and we warn them that if they do not listen we will have to use our power to convince them.

That power is the power of the people, and ultimately we know that the masses will not only demand but win full rights in a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic South Africa.

But we are not merely seeking a particular goal. We also propose a particular route for realizing it, and that is a route that involves the people all the way through. We do not want a process where a deal is struck over the heads of the people and their job is merely to applaud. The government resists this at all costs because the question of how a constitution is made, how negotiations take place, is vitally connected to whether or not a democratic result ensues.

The present government wants to remain in office during the entire process of transition. Our view is that this is unacceptable. This government has definite negotiation goals. It cannot be allowed to use its powers as a government to advance its own cause and that of its allies and to use those same powers to weaken the ANC.

And this is exactly what they are doing. They have unbanned the ANC, but we operate under conditions substantially different from that of other organizations. We do not have the same freedom to organize as does Inkatha and other organizations allied to the apartheid regime. Our members are harassed and even killed. We are often barred from holding meetings and marches.

We believe that the process of transition must be controlled by a government that is not only capable and willing to create and maintain the conditions for free political activity. It must also act with a view to ensuring that the transition is towards creating a genuine democracy and nothing else.

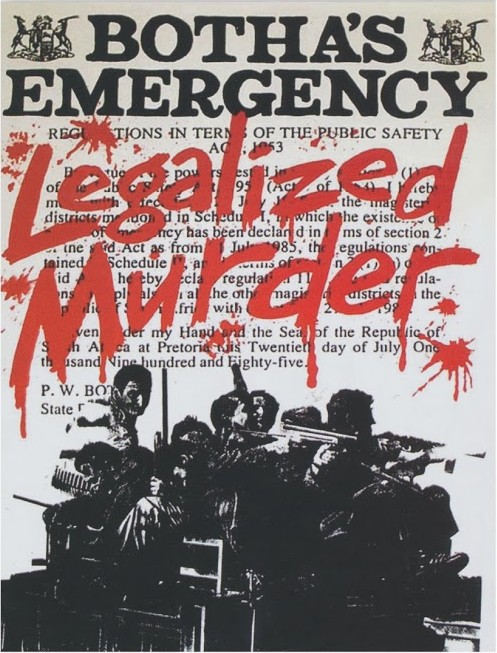

Poster denouncing state of emergency laws imposed by the government of P.W. Botha to suppress the anti-apartheid movement. |

We have had ten thousand people murdered in this violence since 1984 and two thousand this year alone. We have always said that this government that boasts of its professional police force is perfectly capable of ending this violence and prosecuting the perpetrators. Not only are they unwilling, we now have conclusive evidence, published in independent newspapers, of their complicity in this violence.

The violence has been used in a systematic attempt to advance the power of Inkatha as a potential alliance partner of the National Party. There is now conclusive evidence of funds provided by the government -- that is, taxpayers' money -- to Inkatha.

All of this indicates the necessity to create an interim government of national unity to oversee the transition. We need a government enjoying the confidence of broad sections of the population to rule over this delicate period, ensuring that counterrevolutionaries are not allowed to upset the process and ensuring that constitution making operates within an atmosphere free of repression, intimidation, and fear.

The constitution itself, we believe, must be made in the most democratic manner possible. To us, that can best be achieved through electing representatives to a constituent assembly with a mandate to draft the constitution. There are organizations that challenge the ANC's claim to be the most representative organization in the country. If that is true, let them prove their support at the ballot box.

To ensure that ordinary people are included in this process we are circulating and discussing our own constitutional proposals and draft bill of rights. We want these to be discussed in all structures of our alliance -- that is, the ANC, South African Communist Party, and Congress of South African Trade Unions, and amongst the people in general. That way, when people vote for the ANC to represent them. in a constituent assembly, they will know not only what the ANC stands for generally, but what type of constitution we want.

Naturally these constitutional proposals are subject to re-vision on the basis of our consultations with our membership, the rest of the alliance, and the public generally. We want to create a constitution that enjoys widespread support, loyalty, and respect. That can only be achieved if we really do go to the people.

Nelson Mandela and then wife Winnie Mandela at a rally of the South African Communist Party. At right, the party's leader Joe Slovo. |

The ANC is not a communist party but a broad liberation movement, including amongst its members Communists and non-Communists. Anyone who is a loyal member of the ANC, anyone who abides by the discipline and principles of the organization, is entitled to belong to the organization.

Our relationship with the SACP as an organization is one of mutual respect. We unite with the SACP over common goals, but we respect one another's independence and separate identity. There has been no attempt whatsoever on the part of the SACP to subvert the ANC. On the contrary, we derive strength from the alliance.

We have no intention whatsoever of heeding the advice of those who suggest we should break from this alliance. Who is offering this unsolicited advice? In the main it is those who have never given us any assistance whatsoever. None of these advisers have ever made the sacrifices for our struggle that Communists have made. We are strengthened by this alliance. We shall make it even stronger.

We are in a phase of our struggle where victory is in sight. But we have to ensure that this victory is not snatched from us. We have to ensure that the racist regime feels maximum pressure right till the end and that it understands that it must give way, that the road to peace, freedom, and democracy is irresistible.

That is why sanctions must be maintained. This is not the time to reward the apartheid regime. Why should they be rewarded for repealing laws which form what is recognized as an international crime? Apartheid is still in place. The regime must be forced to dismantle it, and only when that process is irreversible can we start to think of lifting the pressure,

We are very concerned at the attitude that the Bush administration has taken on this matter. It was one of the few governments that was in regular touch with us over the question of sanctions, and we made it clear that lifting sanctions was premature. That administration nevertheless, without consulting us, merely informed us that American sanctions were to be lifted. We find that completely unacceptable.

Fidel Castro warmly greets Nelson Mandela on his arrival in Cuba in 1991. |

You are with us because both of our organizations, the Communist Party of Cuba and the ANC, are fighting for the oppressed masses, to ensure that those who make the wealth enjoy its fruits. Your great apostle Jose Martí said, "With the poor people of this earth I want to share my fate."

We in the ANC will always stand with the poor and rightless. Not only do we stand with them. We will ensure sooner rather than later that they rule the land of their birth, that in the words of the Freedom Charter, "The people shall govern." And when that moment arrives, it will have been made possible not only by our efforts but through the solidarity, support, and encouragement of the great Cuban people.

I must close my remarks by referring to an event which you have all witnessed. Comrade Fidel Castro conferred upon me the highest honour this country can award. I am very much humbled by this award, because I do not think I deserve it. It is an award that should be given to those who have already won the freedom of their peoples. But it is a source of strength and hope that this award is given for the recognition that the people of South Africa stand on their feet and are fighting for their freedom. We sincerely hope that in these days that lie ahead we will prove worthy of the confidence which is expressed in this award.

Long

live

the

Cuban

revolution!

Long live Comrade Fidel Castro!

(Source: How Far We Slaves Have Come, By Nelson Mandela and Fidel Castro (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991). Photos: ANC Archives; UDF Archives; Canadian Network on Cuba; "Cien Imagenes de la Revolucion Cubana, 1953-1996," Oficina de Publicaciones del Consejo de Estado; Instituto Cubano del Libro; Editorial Arte y Literatura, Havana, 2004.)

Read The Marxist-Leninist Daily

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

Post-apartheid South Africa emerged

at the end of the bi-polar division of

the world and the neo-liberal attack on the world's people in the

1990s. For

any country to overcome the obstacles and pressures of imperialism in a

manner that favours its people, not the global monopolies, is no small

feat.

This is all the more true in a country such as South Africa, which

bears the

scars and lacerations of the more than 300 years of racist rule. As the

last

colony to gain its freedom in the epic saga of the continental wide

struggle to

throw off the yoke of colonial domination, South Africa illustrates the

challenges that face a genuine nation-building project.

Post-apartheid South Africa emerged

at the end of the bi-polar division of

the world and the neo-liberal attack on the world's people in the

1990s. For

any country to overcome the obstacles and pressures of imperialism in a

manner that favours its people, not the global monopolies, is no small

feat.

This is all the more true in a country such as South Africa, which

bears the

scars and lacerations of the more than 300 years of racist rule. As the

last

colony to gain its freedom in the epic saga of the continental wide

struggle to

throw off the yoke of colonial domination, South Africa illustrates the

challenges that face a genuine nation-building project.