No. 52

November 11, 2024

November 11, 2024

Remembrance Day

In

Wartime

Stephan

G. Stephansson

In Europe's reeking slaughter-pen

They mince the flesh of

murdered men,

While swinish merchants, snout in trough,

Drink

all the bloody profits off!

• The Time Has Come for Human Beings

to Make History

• The Day the Armistice Was Signed to End World War I

• Unacceptable Presence of NATO at Wreath-Laying Ceremonies! Get Canada Out of NATO! Dismantle NATO!

For Your Information on World War I

• Appeal to the Soldiers of All the Belligerent Countries

Canada

• War

Measures Act of

1914 and Internment of

Canadians

as "Enemy Aliens"

• Opposition to Conscription in Canada and Quebec

• Recruitment of Indigenous Peoples

• Black Construction Battalion

Britain

• British Movement of

Conscientious Objectors:

The Men Who Said

No

• Opposition in Britain to the War and Criminalization of Conscience

• Organizing to Oppose Conscription and

Defend

Conscientious Objectors

• Civil Service and Non-Combat Roles in

the Military

for Objectors

November

11, 2024

Remembrance Day

The Time Has Come for Human Beings

to Make History

As is well known, November 11 marks the day in 1918 when on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, the armistice treaty which ended World War I was signed. Crocodile tears will be shed by the warmongers as they blame their adversaries and especially Russia which launched the Great October Revolution in 1917, took Russia out of the war and cancelled all unequal imperialist treaties. But they also use the occasion to blame Russia today as an avowed enemy. This despite the fact that the Soviet Union bore the brunt of the losses and damage caused during World War II in Europe, along with the working people of Europe, the Jews, the Roma, those the Hitlerites considered deviants, as well as the communists, anti-fascist resistance fighters and Soviet prisoners of war. They will have a very hard time this year presenting the U.S. as the champion of freedom, democracy and peace, as those who liberated Europe along with the British and, maybe, a few French and Polish aristocrats.

Already, the NATO Association of Canada has informed on its Instagram account that for November 11 this year, "we are proud to announce multiple NATO Wreath Laying Ceremonies across the country [...] in Vancouver, Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto. [...] Join us in commemorating those who sacrificed greatly to protect the values we hold dear."

The Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist) resolutely opposes such attempts to militarize culture by militarizing wreath-laying ceremonies which honour Canadians and Quebeckers who were sacrificed as cannon fodder in World War I. Through sleight of hand, the NATO Association of Canada conflates all those whose lives were sacrificed in World War I, which was an inter-imperialist war for the redivision of the world, with those who fought Nazi Fascism in World War II and with the crimes NATO has committed since World War II and the U.S./NATO wars of destruction, regime change, and brutal war crimes they are committing today. This includes assassinations, torture, mass killings and now genocide in Gaza and massive destruction, displacement and killings in Lebanon. All of this, the NATO Association of Canada says uphold the values Canadians hold dear.

This is said at a time today when the U.S. democracy and the democracy of its Genocide Cartel, which includes Canada, and their claims to stand for peace, freedom and democracy, have never been so isolated on the world scale. Far from democracy, the U.S. election results show a country entering a period of police rule which is suffering profound psychological trauma, a profound existentialist crisis. So too the response of the ruling circles in Canada and Quebec to the election of Donald Trump as next president of the United States reflects the same thing. In Canada and Quebec, it is expressed in heightened hysteria about immigrants and refugees invading Canada, Trump imposing more tariffs on trade, more assaults on women and immigrants and the need to save Canada by walking in lockstep with the new U.S. administration.

This

is a time to strengthen the work of CPC(M-L) and all Canadians,

Quebeckers and Indigenous Peoples to set another agenda, an agenda

which puts the claims they are within their rights to lay on society

which defend the rights of all, in first place.

This

is a time to strengthen the work of CPC(M-L) and all Canadians,

Quebeckers and Indigenous Peoples to set another agenda, an agenda

which puts the claims they are within their rights to lay on society

which defend the rights of all, in first place.

This is the

time to advocate for the mass democratic renewal of the electoral

process and a modern Constitution and support the modern conception

that our peoples' identities are and always have been forged in their

resistance struggle against exploitation, oppression, colonial rule and

Anglo-Canadian arrangements which deprive them of political power. A

people is not defined by the identity of two founding races imposed on

them first by the colonial power, and then sustained by the

Anglo-Canadian state to divide the people and permit Canada's

integration into the U.S. war machine and that of Quebec along with it.

Today, the dregs of the deposed ruling classes from the time of the Russian Revolution and the reactionary forces of this period continue to be consumed with a spectre of communism. It is a spectre which haunts them every time they engage in practices which go against the people's interests. They have created a stereotype of socialism and communism and defence of the rights of peoples of the world to wage resistance struggles against their enslavers and oppressors, which they equate with terrorism. The stereotypes are figments of their deranged imaginations, dominated by a morbid preoccupation with their own demise.

To keep the peoples out of power, the ruling elites of countries that espouse what is called "representative democracy" and its "liberal democratic institutions" push rule through ministerial prerogative powers that are exercised above the rule of law. This is then called a model of a democracy that should be imposed on others. It is a model which has no credibility whatsoever because you cannot both sanction genocide and claim to defend democracy. Meanwhile the so-called rules-based international order espoused by those who are backing genocide and war threatens to destroy any who refuse to submit to their dictate. At the same time, maintaining the use of veto power by a select few countries in the United Nations who are charged with defending the international rule of law, in actuality preserves power relations which keep entire peoples and nations out of power, and is used to shield those who commit genocide and their backers from being held to account.

Propaganda about the "enemy within" and "foreign interference" is used to divert the attention of the workers and peoples of the world both from how decision-making takes place within what are called the paradigms of democracy, and how to create a system which is able to effectively channel all the human and material resources of their countries in a manner which favours them.

It is most obvious today with attempts to impose governments of police powers as the U.S. imperialists and their allies, including Canada are doing, as well as the Legault government in Quebec and provincial governments across the country. Never has the system called a representative democracy and its claims been so isolated on the world scale as is the case today. An order is not something which can be imposed from above.

In fact, the more the counterrevolution launched since the fall of the former Soviet Union deepens, the more the significance of the Great October Socialist Revolution to human history increases. Since the collapse of the former Soviet Union in 1989-91 as a result of the restoration of capitalism in that country and imposition of a rule which deprived the people of Soviet power, the consequences of the U.S.-led brutal neo-liberal anti-social offensive and the wars it has unleashed to achieve regime change and domination continue to cause tremendous damage to the peoples of the world and Mother Earth. The crimes of the U.S. and its allies today are unprecedented. Those committing these crimes include Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand. Their intelligence agencies together with those of the U.S., make up the so-called "Five Eyes" political police services which are dictating policy which permits the takeover of the state by police powers and criminalization of the people in the name of "values." It is only the peoples striving for their own empowerment who can bring this state of affairs to an end.

In the conditions of the retreat of revolution, the extreme violence unleashed by the U.S./Zionist killing machine in Gaza, as well as the U.S./NATO proxy war in Ukraine and in other countries of the world is a state of affairs possible because the initiative is not in the hands of the peoples. So long as the big powers by entering into cartels and coalitions with other countries are expected to stop it, the suffering of the peoples will continue to increase.

The current international system is discredited because it does not stop the violence, the killings, the threats of expanded war. Thus, the peoples are supporting the Resistance Movements, expressing confidence that they will open a way forward which vests sovereignty in the people, not ruling elites.

What it means to have a society such as the one which came into being in 1917 in Soviet Russia is once again relevant. Soviet Russia created a new society by establishing Soviet power which put the initiative in the hands of the workers, peasants and patriotic intelligentsia. It put the building of a revolutionary party of the working class on the basis of Soviet power at the centre to make sure the workers were educated and trained to decide all matters of concern in a manner which favoured their interests and then they led the masses of the people to do likewise. This is what is to be achieved today on a new basis, with the people working as one to provide the rights of all with guarantees of their own making.

On this occasion,

we salute all those who have waged and continue to

wage a courageous resistance in our country. This includes not only the

workers from all sectors of the economy, the self-sacrificing health

care personnel, teachers and education workers and peoples in the towns

and villages

giving their all to stop the privatization and sellout of our resources

but importantly, the youth and all those speaking in their own names to

support the Resistance movements in Palestine, Lebanon, Haiti, Cuba,

India and all countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean,

Oceania, Europe

and the United States.

On this occasion,

we salute all those who have waged and continue to

wage a courageous resistance in our country. This includes not only the

workers from all sectors of the economy, the self-sacrificing health

care personnel, teachers and education workers and peoples in the towns

and villages

giving their all to stop the privatization and sellout of our resources

but importantly, the youth and all those speaking in their own names to

support the Resistance movements in Palestine, Lebanon, Haiti, Cuba,

India and all countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean,

Oceania, Europe

and the United States.

The peoples are on the cusp of making great headway in humanity's fight to turn things around in their own favour but these are trying times which contain great dangers. We must strengthen ourselves by taking up the program of organizing the people on a new basis.

As we commemorate all the lives lost in World War I, the Duty of Memory leads us to draw the conclusion that we must all work hard to strengthen the mass movements for peace, freedom and democracy. We must strengthen the work to build a mass communist revolutionary party which trains its members in mass democratic methods of work and decision-making. Such a party must be capable of creating transitional forms of organization within all spheres of endeavour, also based on mass democratic ideological and political mobilization which empowers the working class and people to take the decisions on all matters which affect their lives.

The Day the Armistice Was

Signed

to End World War I

On November 11,

1918, the Armistice which brought World War I to an end was signed,

marking the end of the war. A slaughterhouse of unprecedented

proportions, World War I was referred to as the "war to end all wars."

The Treaty of Versailles was finally signed by Germany and the Allied

Nations on June 28, 1919, formally ending World War I.

On November 11,

1918, the Armistice which brought World War I to an end was signed,

marking the end of the war. A slaughterhouse of unprecedented

proportions, World War I was referred to as the "war to end all wars."

The Treaty of Versailles was finally signed by Germany and the Allied

Nations on June 28, 1919, formally ending World War I.

World War I was an inter-imperialist war, a war in which working men were sent to be slaughtered as empires clashed to re-divide the world. World War I left 9 million soldiers dead and 21 million wounded. In addition, at least 5 million civilians died from disease, starvation, or exposure. The influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918 killed an estimated 50 million people. One fifth of the world's population was attacked by this deadly virus.

The war also marked a turning point in history. In 1917, the Russian working class and people organized the Great October Socialist Revolution and took Russia out of the war.

When Soviet power was established, Winston Churchill called for the crushing of the baby "in the cradle." In the aftermath of the war, 14 foreign powers, including Canada, militarily intervened in order to foment civil war, seize Soviet Russia's assets for themselves and put an end to the revolution and Soviet power. But Soviet power prevailed and they were defeated. Far from being crushed, the Great October Socialist Revolution led to the advance of society, to its vigorous development and the unprecedented release of human initiative.

Drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change occurred in Europe, Asia and Africa, even in areas outside those directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war -- the Russian Czarist Empire in 1917 and then the Ottoman Empire, the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. Old countries were abolished, new ones were formed and boundaries were redrawn. The League of Nations was established in 1919, under the Treaty of Versailles "to promote international cooperation and to achieve peace and security."

The high ideals of a "War to End All Wars," of duty to King and Country, and to empire, were shown to be a cover, a false justification, for the horrendous clash of the imperialist warmongers which took place during World War I. Yet these same values are promoted at this time under the rubric "Lest we forget."

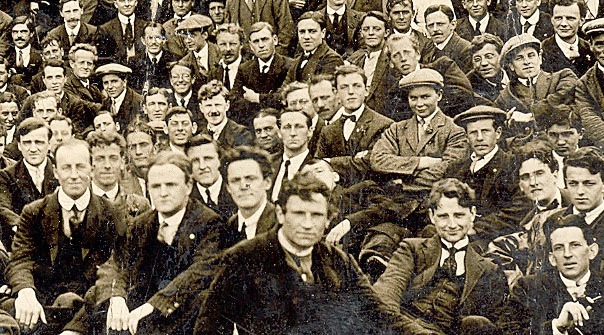

Demonstration against conscription

in Victoria Square, Montreal, May 17, 1917. Working people in Quebec

could find no convincing reason to sacrifice their lives for the glory

of the British Empire. The Canadian government imposed conscription in

August 1917.

Demonstration against conscription

in Victoria Square, Montreal, May 17, 1917. Working people in Quebec

could find no convincing reason to sacrifice their lives for the glory

of the British Empire. The Canadian government imposed conscription in

August 1917.

Bourgeois historiography refers to Canada's "coming of age" as a result of its role in World War I where it allegedly proved itself worthy of making decisions over its own foreign policy. The sacrifice of Canadian youth as cannon fodder in the trenches of Europe is said to have provided proof that Canada could be entrusted with the conduct of its own foreign policy and break ties with the British Imperial Parliament in this regard. This disinformation seeks to imbue Canadians with a chauvinist outlook that portrays Canada as a major Entente Power fit to sit at the table that divides the spoils of war. In fact, it made Canada a yes-man at the service of the understandings between Britain and France to keep Germany out, while they sympathized with all the new organizations hostile to Soviet Russia.

Today, Canada's

warmongering is presented as a foundational Canadian value. But the

sacrifice of Canadians contradicts official accounts. Their sacrifice

was made not for freedom but on behalf of empire. Canada's independence

was not secured by sending Canada's youth to participate in the charnel

house of imperialist slaughter that was World War I, a war of division

between the empires of the day to secure sources of raw materials,

cheap labour, zones for the export of capital and strategic influence.

On the contrary, Canada's ruling elite secured a place for itself as a

yes-man of first the

British and then the U.S. imperialists, while the movement of the

people persists for a genuine nation-building project in which the

natural and human resources and decision-making power serve the people,

not the rich.

Today, Canada's

warmongering is presented as a foundational Canadian value. But the

sacrifice of Canadians contradicts official accounts. Their sacrifice

was made not for freedom but on behalf of empire. Canada's independence

was not secured by sending Canada's youth to participate in the charnel

house of imperialist slaughter that was World War I, a war of division

between the empires of the day to secure sources of raw materials,

cheap labour, zones for the export of capital and strategic influence.

On the contrary, Canada's ruling elite secured a place for itself as a

yes-man of first the

British and then the U.S. imperialists, while the movement of the

people persists for a genuine nation-building project in which the

natural and human resources and decision-making power serve the people,

not the rich.

Today, more than 100 years after the end of World War I, Canada has been integrated into the U.S. imperialist war machine while the U.S. and NATO and their allies expand their interference and aggression and threaten war against countries that will not submit to their dictate. At the same time, the Canadian government, in the service of this agenda, is setting the stage to use its police powers to deem opposition to war and aggressive alliances such as NATO as threats to national security.

Today, Canadians and Quebeckers stand second to none amongst the peoples of the world opposing genocide and imperialist aggression and war. They have done so by arguing out their convictions in the face of an onslaught of disinformation that the brutal crimes carried out by U.S. imperialism, NATO and Zionism represent enlightenment, defence of human rights, peace, democracy and freedom. The peoples' ongoing work to oppose these crimes and end Canadian complicity is part and parcel of the important work to bring about new arrangements that will Make Canada a Zone for Peace.

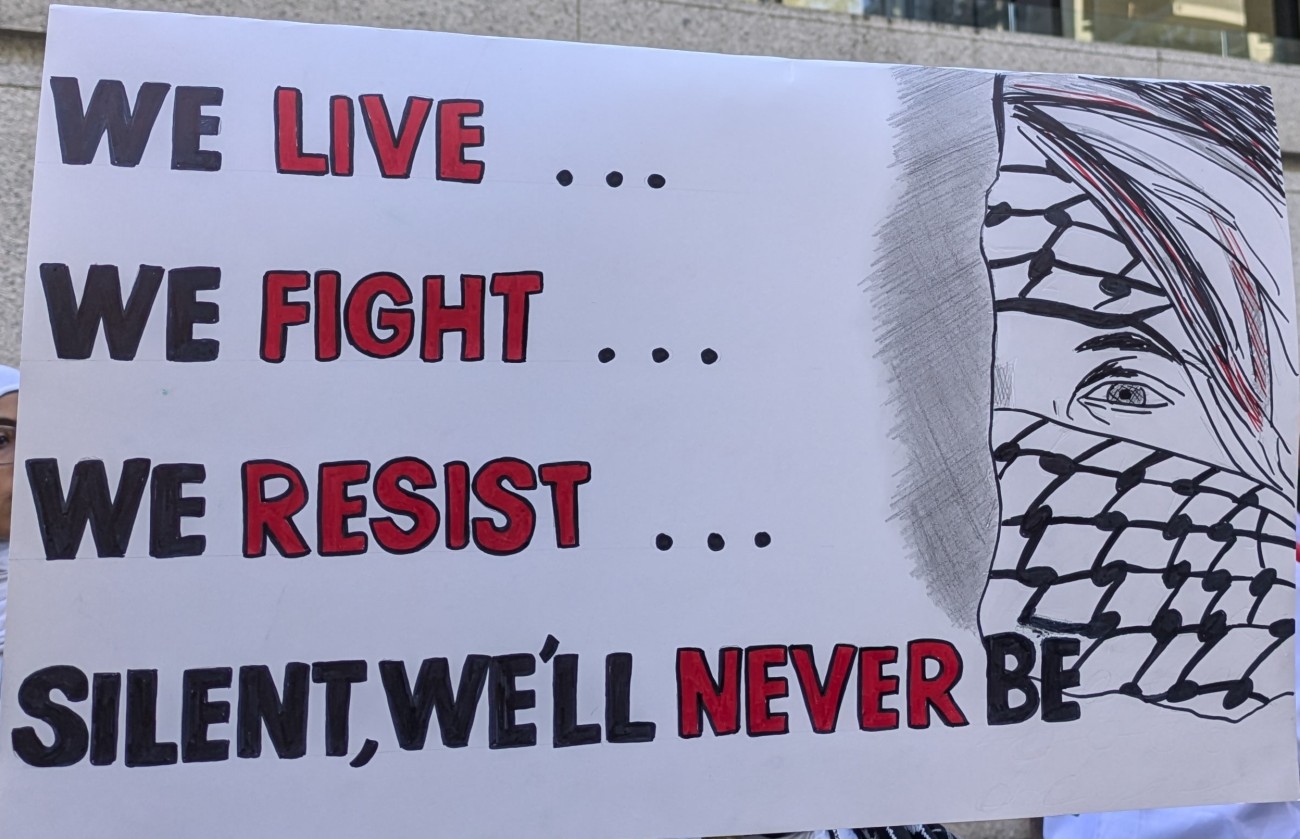

First National Day of

Action against the U.S./Israeli genocide in Palestine, November 25, 2023

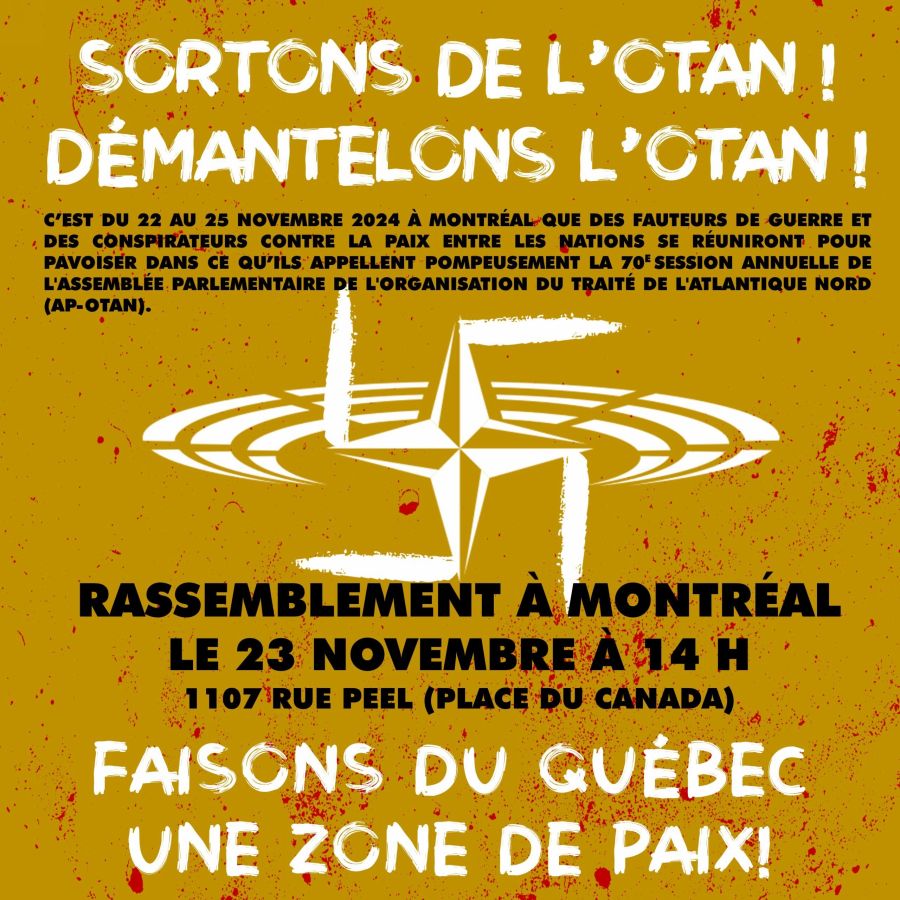

Unacceptable Presence of

NATO

at Wreath-Laying Ceremonies!

Get Canada Out

of NATO! Dismantle NATO!

The NATO Association

of Canada informed on its

Instagram account that this year for November 11, "[W]e are proud to

announce multiple NATO Wreath Laying Ceremonies across the country

[...] in Vancouver, Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto.[...] Join us in

commemorating those who sacrificed greatly

to protect the values we hold dear."

The NATO Association

of Canada informed on its

Instagram account that this year for November 11, "[W]e are proud to

announce multiple NATO Wreath Laying Ceremonies across the country

[...] in Vancouver, Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto.[...] Join us in

commemorating those who sacrificed greatly

to protect the values we hold dear."

The presence of NATO -- a warmongering alliance led by the U.S. imperialists that is currently armed to the teeth in Europe and waging a U.S. proxy war in Ukraine -- at wreath-laying ceremonies to remember those who perished in World War I, is unacceptable. NATO's values are the opposite of what those Canadians who were used as cannon-fodder by the British in that war upheld. The ceremonies also commemorate those who perished in World War II. Here as well, NATO falsely claims to represent the aspirations of those who fought and died as part of the united anti-fascist front of the peoples. Its claims are bogus because it was founded on an anti-communist basis that put Nazi war criminals in charge of its operations. Thus, it is similarly unacceptable that NATO is welcomed to honour those who made sacrifices to eliminate the scourge of fascism.

To show what NATO stands for, we are republishing below an article by Dougal MacDonald titled "U.S. Built NATO by Putting Nazi War Criminals in Charge," originally published by TML Daily on March 28, 2022.

U.S. Built NATO by Putting Nazi War Criminals in Charge

As the situation in Ukraine develops, imperialist propaganda continues to promote the false notion that NATO (and by default the U.S.) is somehow an alliance for peace. This fraud is being perpetuated to try to convince people that the situation in Ukraine can be boiled down simply to "bad" Russia on one side and "good" U.S. and NATO on the other. Therefore, everyone should support the U.S. and NATO and oppose Russia and that will somehow bring about peace on earth.

Aside from the fact that the whole history of the U.S. and NATO focuses on war against other countries rather than peace, this big lie is also refuted by the history of NATO itself.

The facts show that as soon as the Hitlerites surrendered at the end of the Second World War, with the Soviet Union playing the main role in their defeat, the Anglo-Americans began helping Germany rebuild, economically and militarily. Germany was to serve as a bulwark against the socialist Soviet Union, the Anglo-Americans' supposed wartime ally, now designated their main foe. This post-war plan, which was already being hatched before the war ended, included the formation of the aggressive NATO alliance in 1949 within which a number of Hitler's military leaders played key roles.

|

One typical example is General Adolf Heusinger, a career military officer who, with the outbreak of the Second World War, became part of the German headquarters field staff and helped plan the Nazi invasions of Poland, Denmark, Norway, France and the Low Countries. The Nazis perpetrated against Poland one of the worst crimes history has ever known. Poland suffered the largest number of casualties per capita of any European country, with a total of about six million people killed. Heusinger rose quickly through the Wehrmacht's administrative ranks and in 1944 was appointed Adolf Hitler's Chief of the General Staff of the Army.

After the war, Heusinger was interrogated by the Americans but not put on trial. A declassified CIA document says: "Upon surrendering to U.S. Army authorities in May 1945, the question of [Heusinger's] implication as a war criminal arose in connection with certain orders he signed and forwarded which sealed the fate of captured Russian political indoctrination officers and Allied commandos. However, in view of Heusinger's cooperative attitude at Nuremberg and the fact that he had only initialed the orders in transmittal, no action was undertaken. Instead, Heusinger served as a research consultant without pay for the Office of the United States Chief of Counsel for War Crimes at Nuremberg periodically between 1945 and 1948."

So instead of being put on trial for war crimes, Heusinger became an advisor on military matters to Konrad Adenauer, appointed the first Chancellor of West Germany in 1949. One of Adenauer's first acts was denunciation of the denazification of Germany and an amnesty for Nazi war criminals. By the end of January 1951, almost 800,000 war criminals had benefited from the amnesty. Adenauer and John J. McCloy, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany and later Chairman of the Rockefellers' Chase Manhattan Bank and the Ford Foundation, were linked by marriage. McCloy played a key role in the early release from prison of many Nazi war criminals convicted at Nuremburg, including industrialists Alfried Krupp and Friedrich Flick who went right back to enriching themselves by taking leading roles in the post-war German economy.

With the 1955 establishment of the Bundeswehr, the reconstituted West German Armed Forces, Heusinger returned to military service, and was appointed Lieutenant-General in 1955. In 1957, he was promoted to full general and named the first Inspector-General of the Bundeswehr. He served in that capacity until 1961. In 1961, Heusinger was appointed Chairman of the NATO Military Committee, making him the senior military spokesperson for NATO and in 1963 he also became NATO's chief of staff, serving in that capacity until 1964.

Many other prominent ex-Nazis followed similar paths, in particular serving as Commanders in Chief of Allied Central Forces Europe. Here are just a few examples:

- General Hans Speidel, who participated in the invasions of Poland, France, and the Soviet Union, played a key role in German rearmament and integration into NATO, and in 1957 became Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe.

- Sturmführer Dr. Eberhard Taubert worked with Goebbels in the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda where he was responsible for designing the yellow badge for Jews. After the war, he eventually became an adviser to ex-Nazi Franz Josef Strauss, German Minister of Defence from 1956-62, and was assigned by Strauss to NATO's "Psychological Warfare Department" which spewed anti-communist propaganda just as Goebbels' ministry had during the war.

- Nazi Admiral and U-Boat commander Friedrich Guggenberger, whose U-boat sank 17 allied ships, later served as Deputy Chief of Staff in the NATO command Armed Forces North (AFNORTH), 1968-72.

- Johannes Steinhoff, a Luftwaffe fighter pilot, was made Chairman of the NATO Military Committee 1971-74, holding other NATO positions prior to that.

- Johann von Kielmansegg, General Staff officer to the High Command of the Wehrmacht, 1942-44, was NATO's Commander in Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe, 1967-68.

- Ernst Ferber, a major in the Wehrmacht, was NATO's Commander in Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe, 1973-75.

- Karl Schnell, First General Staff officer of the LXXVI Panzer Corps, was NATO's Commander in Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe, 1975-77.

- Franz Joseph Schulze, Chief of the Third Battery of the Flak Storm Regiment 241, was NATO's Commander in Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe, 1977-79.

- Ferdinand von Senger und Etterline, Lieutenant of the 24th Panzer Division of the German Sixth Army, was NATO's Commander in Chief of Allied Forces Central Europe, 1979-83.

The historical

facts are clear. Instead of facing trial and

paying for the countless crimes they planned and committed, Heusinger,

Speidel and other prominent Nazi war criminals were given a free pass

by the Anglo-Americans. Instead of being made accountable, they were

rewarded for their service

to the Nazis by being given key roles in rebuilding the West German

army to oppose the Soviet Union and by being appointed as key NATO

functionaries in Europe for the same nefarious purposes. There is a

clear connection from the Nazis to the U.S. occupiers to the West

German military to NATO that

once again exposes NATO's true role.

The historical

facts are clear. Instead of facing trial and

paying for the countless crimes they planned and committed, Heusinger,

Speidel and other prominent Nazi war criminals were given a free pass

by the Anglo-Americans. Instead of being made accountable, they were

rewarded for their service

to the Nazis by being given key roles in rebuilding the West German

army to oppose the Soviet Union and by being appointed as key NATO

functionaries in Europe for the same nefarious purposes. There is a

clear connection from the Nazis to the U.S. occupiers to the West

German military to NATO that

once again exposes NATO's true role.

NATO has never been a force for peace or a defence against some fictional Soviet threat. Instead, it has always been an aggressive military alliance that exists solely to serve the aims of U.S. imperialist domination of the world.

For Your Information on World War I

Appeal to the Soldiers of

All the

Belligerent

Countries

Brothers, soldiers!

We are all worn out by this frightful war, which has cost millions of lives, crippled millions of people and caused untold misery, ruin, and starvation.

And more and more people are beginning to ask themselves: What started this war, what is it being waged for?

Every day it is becoming clearer to us, the workers and peasants, who bear the brunt of the war, that it was started and is being waged by the capitalists of all countries for the sake of the capitalists' interests, for the sake of world supremacy, for the sake of markets for the manufacturers, factory owners and bankers, for the sake of plundering the weak nationalities. They are carving up colonies and seizing territories in the Balkans and in Turkey -- and for this the European peoples must be ruined, for this we must die, for this we must witness the ruin, starvation and death of our families.

The capitalist class in all countries is deriving colossal, staggering, scandalously high profits from contracts and war supplies, from concessions in annexed countries, and from the rising price of goods. The capitalist class has imposed contribution on all the nations for decades ahead in the shape of high interest on the billions lent in war loans. And we, the workers and peasants, must die, suffer ruin, and starve, must patiently bear all this and strengthen our oppressors, the capitalists, by having the workers of the different countries exterminate each other and feel hatred for each other.

Are we going to continue submissively to bear our yoke, to put up with the war between the capitalist classes? Are we going to let this war drag on by taking the side of our own national governments, our own national bourgeoisies, our own national capitalists, and thereby destroying the international unity of the workers of all countries, of the whole world?

No, brother soldiers, it is time we opened our eyes, it is time we took our fate into our own hands. In all countries popular wrath against the capitalist class, which has drawn the people into the war, is growing, spreading, and gaining strength. Not only in Germany, but even in Britain, which before the war had the reputation of being one of the freest countries, hundreds and hundreds of true friends and representatives of the working class are languishing in prison for having spoken the honest truth against the war and against the capitalists. The [February] revolution in Russia is only the first step of the first revolution; it should be followed and will be followed by others.

The new government in Russia -- which has overthrown Nicholas II, who was as bad a crowned brigand as Wilhelm II -- is a government of the capitalists. It is waging just as predatory and imperialist a war as the capitalists of Germany, Britain, and other countries. It has endorsed the predatory secret treaties concluded by Nicholas II with the capitalists of Britain, France, and other countries; it is not publishing these treaties for the world to know, just as the German Government is not publishing its secret and equally predatory treaties with Austria, Bulgaria, and so on.

On April 20 the Russian Provisional Government published a Note re-endorsing the old predatory treaties concluded by the tsar and declaring its readiness to fight the war to a victorious finish, thereby arousing the indignation even of those who have hitherto trusted and supported it.

But, in addition to the capitalist government, the Russian revolution has given rise to spontaneous revolutionary organisations representing the vast majority of the workers and peasants, namely, the Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies in Petrograd and in the majority of Russia's cities. Most of the soldiers and some of the workers in Russia -- like very many workers and soldiers in Germany -- still preserve an unreasoning trust in the government of the capitalists and in their empty and lying talk of a peace without annexations, a war of defence, and so on.

But, unlike the capitalists, the workers and poor peasants have no interest in annexations or in protecting the profits of the capitalists. And, therefore, every day, every step taken by the capitalist government, both in Russia and in Germany, will expose the deceit of the capitalists, will expose the fact that as long as capitalist rule lasts there can be no really democratic, non-coercive peace based on a real renunciation of all annexations, i.e., on the liberation of all colonies without exception, of all oppressed, forcibly annexed or underprivileged nationalities without exception, and the war will in all likelihood become still more acute and protracted.

Only if state power in both the, at present, hostile countries, for example, in both Russia and Germany, passes wholly and exclusively into the hands of the revolutionary Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which are really capable of rending the whole mesh of capitalist relations and interests, will the workers of both the belligerent countries acquire confidence in each other and be able to put a speedy end to the war on the basis of a really democratic peace that will really liberate all the nations and nationalities of the world.

Brothers, soldiers!

Let us do everything we can to hasten this, to achieve this aim. Let us not fear sacrifices -- any sacrifice for the workers' revolution will be less painful than the sacrifices of war. Every victorious step of the revolution will save hundreds of thousands and millions of people from death, ruin, and starvation.

Peace to the hovels, war on the palaces! Peace to the workers of all countries! Long live the fraternal unity of the revolutionary workers of all countries! Long live socialism!

Central Committee of the R.S.D.L P. Petrograd

Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.

Editorial Board of Pravda

(Lenin Collected

Works, Volume 24)

Canada

War Measures Act of 1914 and Internment of Canadians as "Enemy Aliens"

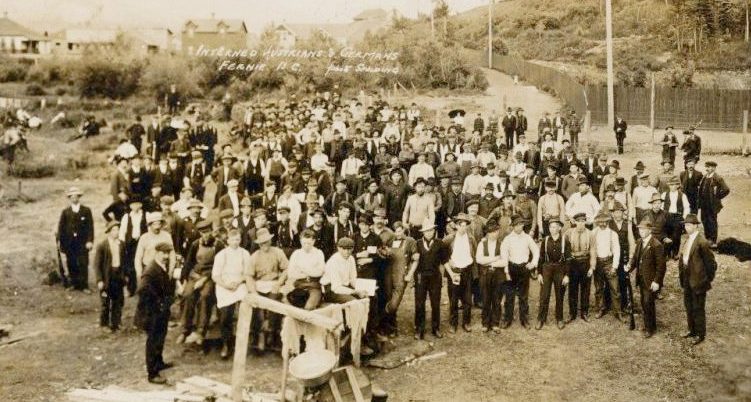

Internment camp in Banff, Alberta.

Internment camp in Banff, Alberta.

Upon Great Britain's declaration of war on Germany, the Borden Conservative government enacted the War Measures Act, in August 1914. The law's sweeping powers allowed the government to suspend or limit civil liberties and provided it the right to incarcerate "enemy aliens."

The term "enemy alien" referred to the citizens of states legally at war with Canada living in Canada during the war.

From 1914 to 1920, Canada interned 8,579 persons as so-called enemy aliens across the country in 24 receiving stations and internment camps. Of that number, 3,138 were classified as prisoners of war, while the others were civilians. The majority of those detained were of Ukrainian descent, targeted because Ukraine was then split between Russia (an ally) and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an enemy of the British Empire. Some of the internees were Canadian-born and others were naturalized British subjects, although most were recent immigrants.

Most internees were young unemployed single men apprehended while trying to cross the border into the U.S. to look for jobs -- attempting to leave Canada was illegal. Eighty-one women and 156 children were interned as they had decided to follow their menfolk into the only two camps that accepted families, in Vernon, BC (mainly Germans) and in Spirit Lake near Amos Quebec (mainly Ukrainians).

Internment camp in Fernie, BC.

Internment camp in Fernie, BC.

Besides those placed in internment camps, another 80,000 "enemy aliens," mostly Ukrainians, were forced to carry identity papers and to report regularly to local police offices. They were treated by the government as social pariahs, and many lost their jobs.

|

|

The internment camps were often located in remote rural areas, including in Banff, Jasper, Mount Revelstoke and Yoho national parks in Western Canada. Internees had much of their wealth confiscated. Many of them were used as forced labour on large projects, including the development of Banff National Park and numerous mining and logging operations. They constructed roads, cleared land and built bridges.

Between 1916-17, during a severe shortage of farm labour, nearly all internees were paroled and placed in the custody of local farmers and paid at current wages. Other parolees were sent as paid workers to railway gangs and mines. Parolees were still required to report regularly to police authorities.

Federal and provincial governments and private concerns benefited from their labour and from the confiscation of what little wealth they had, a portion of which was left in the Bank of Canada at the end of the internment operations on June 20, 1920.

A small number of internees, including men considered to be "dangerous foreigners," labour radicals, or particularly troublesome internees, were deported to their countries of origin after the war, largely from the Kapuskasing camp in Ontario, which was the last to be shut down.

Of those interned, 109 died of various diseases and injuries sustained in the camp, six were killed while trying to escape, and some -- according to a military report -- went insane or committed suicide as a result of their confinement.

Internment camp in Petawawa,

Ontario.

Internment camp in Petawawa,

Ontario.

(Canadian War Museum, Calgary Herald, Wikipedia)

Opposition to Conscription in Canada and Quebec

When in August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany, Canada, as a dominion of the British Empire, was automatically bound to take part.

Robert Laird Borden, then Conservative Prime Minister of Canada, was eager to participate in the war. By Sunday, August 9, 1914, the basic orders-in-council had been proclaimed, and a war session of parliament opened just two weeks after the conflict began. Legislation was quickly passed to secure the country's financial institutions and raise tariff duties on some high-demand consumer items. The War Measures Act 1914, giving the government extraordinary powers of coercion over Canadians, was rushed through all three readings.[1]

Businessman William Price (of Price Brothers and Company -- predecessor of Resolute Forest Products) was mandated to create a training camp at Valcartier, near Quebec City. Some 126 farms were expropriated to expand the camp's area to 12,428 acres (50 square kilometres). "From the start of the conflict, a range of 1,500 targets was built, including shelters, firing positions and signs, making it the largest and most successful shooting range in the world on August 22, 1914. The camp housed 33,644 men in 1914."[2] At the time Valcartier was the largest military base in Canada.

Early in the war, Prime Minister Borden had promised not to conscript Canadians into military service.[3] However, by the summer of 1917, Canada had been at war for nearly three years. More than 130,000 Canadians belonging to the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been killed or maimed.[4] The number of volunteers continuously declined with the growing refusal to serve as cannon fodder for imperialist powers and as a result of the profound impact of the war efforts on the country's economy. There was pressure on all the commonwealth countries and British colonies to continue providing troops for the British imperial war effort, yet the government was not able to provide a convincing argument for working people to agree to sacrifice their lives for the British Empire.

The lack of enthusiasm for the war was such that the Borden government imposed conscription through the Military Service Act, August 29, 1917. It stipulated that "All the male inhabitants of Canada, of the age of eighteen years and upwards, and under sixty, not exempt or disqualified by law, and being British subjects, shall be liable to service in the Militia: Provided that the Governor General may require all the male inhabitants of Canada, capable of bearing arms, to serve in the case of a levée en masse." The law was in force through the end of the war.

Borden also decided that the best way to bring about conscription was through a wartime coalition government. He offered the Liberals equal seats at the Cabinet table in exchange for their support for conscription. After months of political manoeuvring, he announced a Union Government in October, made up of loyal Conservatives, plus a handful of pro-conscription Liberals and independent members of Parliament.

Borden was in his sixth year of his first term. In the months just prior to the election he engineered two pieces of legislation, stacking the Unionist side.

Under previous laws, soldiers were excluded from voting in wartime. The new Military Voters Act allowed all 400,000 Canadian men in uniform, including those who were under age or were British-born, to vote in the coming election.

The second piece of legislation, the Wartime Elections Act, gave women the right to vote for the first time in a federal election -- but only women who were the relatives of Canadian soldiers overseas. With these two laws, a vast new constituency of voters, the majority of whom supported the war effort and conscription, were suddenly enfranchised in time for the election. Borden's Unionists won that election with a majority of 153 seats, only three of which were from Quebec.

Posters to

mobilize women for imperialist war. Poster on left

calls on women eligible to vote under Wartime

Elections

Act to vote

for the Union government.

Conscription

Conscription went into effect January 1, 1918. Exemption boards were set up all over the country, before which a high percentage of men appealed their call-up for service. Besides Quebeckers, who as a whole opposed conscription because they had no intention of fighting for their colonial master, the British Empire, many Canadians across the country were also opposed, including anti-imperialists, farmers, unionized workers, the unemployed, religious groups and peace activists. By February 1918, 52,000 draftees had sought exemption across the country. The lack of support for the war was reiterated by the fact that of more than 400,000 men called up for service, 380,510 appealed through the various options for exemption and appeal in the Military Service Act.

Ultimately, some 125,000 Canadians -- just over a quarter of those eligible to be drafted -- were conscripted into the military. Of these, just over 24,000 were sent to Europe before the war's end.

Many Canadian men simply did not show up when they were called to report and join the army. Winnipeg was second only to Montreal in the percentage of men who did not report or defaulted -- almost 20 per cent of those conscripted compared to around 25 per cent in Montreal, according to reports published in the Winnipeg Telegram at the time. These men were pursued by the police and could receive heavy jail sentences if caught and tried.

Opposition to the War and Conscription in Quebec

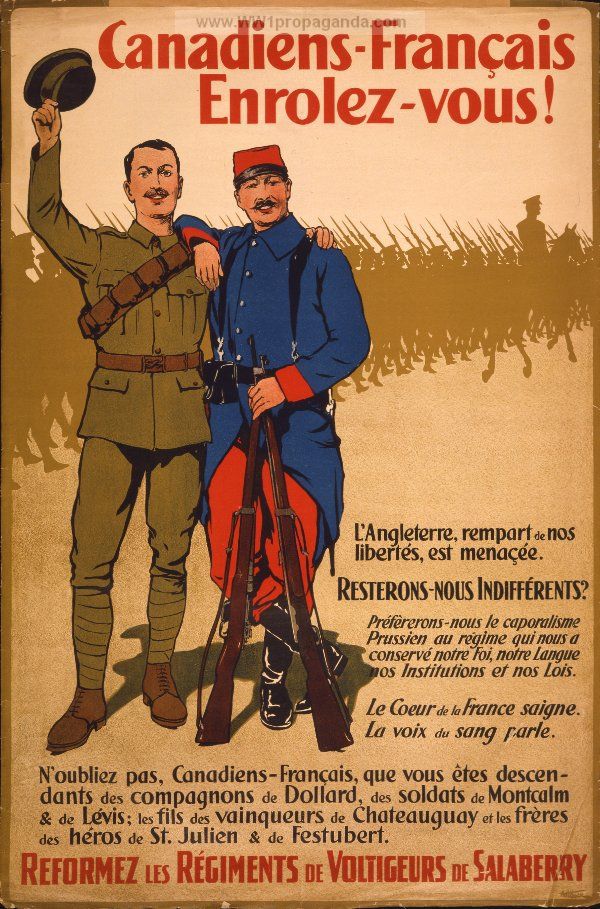

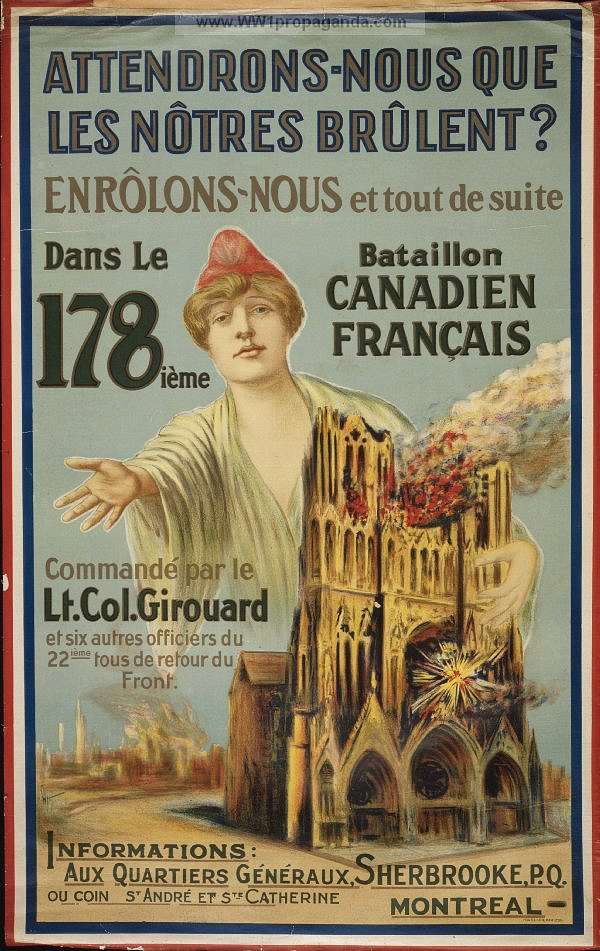

Posters

aimed at getting Quebeckers to join the British Army in World War

I.

Among

the Canadian state's clumsy chauvinist Anglo-Canadian attempts to

recruit Quebeckers to its unjust cause of imperialist war, were those

which exhorted them to enlist on the basis of loyalty to their former

colonial power, France. There were also calls to oppose tyranny by

supporting the new colonial power, Britain; and for the

people to protect themselves from foreign invasion.

On October 15, 1914, the 22nd Regiment was officially created to bolster the involvement of Quebeckers. As the only combatant unit in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) whose official language was French, the 22nd (French Canadian) Infantry Battalion, commonly referred to as the "Van Doos" (from vingt-deux, meaning 22 in French), was subject to more scrutiny than most Canadian units in the First World War. After months of training in Canada and England, the battalion finally arrived in France on September 15, 1915.[5]

In April 1916, the Van Doos participated in one of the unit's most dangerous assignments of the entire war, the Battle of St. Eloi Craters. St. Eloi was fought on a very narrow Belgian battlefield. The fierce battle resulted in heavy casualties. Following St. Eloi, the battalion prepared to take the French village of Courcelette in the Somme sector of France. The battalion suffered hundreds of casualties. To many it showed just how violent war could really be. In the months following the Somme operations, the battalion began suffering from desertion and absence without leave. According to battalion officers, the months following Courcelette witnessed a complete breakdown in troop morale. In the next 10 months, 70 soldiers were brought before a court-martial (48 for illegal absences) and several were executed by firing squad.[6]

Despite the establishment of the Van Doos, the people of Quebec, expressing their anti-war sentiment, were at the forefront of the opposition to conscription. The Canadian establishment at the time blamed Quebeckers for the "the lack of French-Canadian participation in the war."[7]

In Quebec, of the 3,458 individuals from the City of Hull called-up by military authorities who had not been granted an exemption, 1,902 men did not report and were never apprehended, for a total conscription evasion rate of 55 per cent. This was the highest evasion rate of all Canadian registration districts, followed closely by Quebec City at 46.6 per cent, and Montreal at 35.2 per cent. Further, 99 per cent of those called up by the City of Hull applied for an exemption, the highest application rate in all of Canada.[8]

War Measures Act

Quebeckers organized militant protests against attempts by the Canadian government to use its police powers to impose conscription on the working people and youth of Canada and Quebec. The Borden government responded by invoking the War Measures Act to quell this opposition. The government proclaimed martial law and deployed over 6,000 soldiers to Quebec City between March 28 and April 1, 1918.

On the evening of March 28, 1918, federal police raided a bowling alley and arrested the youth there. Faced with the arbitrariness and violence of the police, 3,000 people besieged the police station and continued their demonstration in the streets during the night.

Thousands of demonstrators march to

Place

Montcalm on March 29, 1918.

Thousands of demonstrators march to

Place

Montcalm on March 29, 1918.

The next day, a crowd of nearly 10,000 gathered in front of the Place Montcalm auditorium (currently called Capitole de Quebec), where the conscripts' files were administered. The military, with bayonets and cannons, were called in and shortly after the Riot Act was read, giving them permission to fire.

Within the conditions of the day, the ruling elite in Canada found a wall of resistance among the working people of Quebec to being forcibly sent to war. The aspirations of the Québécois for nationhood had been put down prior to Confederation through force of British arms. Along with the subjugation of the Indigenous Peoples and the settlers in Upper Canada, the basis was laid for the establishment of an Anglo-Canadian state and Confederation. It is not hard to imagine that the Quebec working class would not look favourably on being mowed down on the battlefields of Europe in the service of the British Empire.

Notes

1. "Sir Robert Laird Borden," greatwaralbum.ca.

2. "Les débuts du camp de Valcartier et d'une armée improvisée de toutes piéces," Pierre Vennat, Le Québec et les guerres mondiales, December 17, 2011.

3. Richard Foot, "Election of 1917," August 12, 2015, Canadian Encyclopedia.

4. Ibid.

5. Maxime Dagenais, "The 'Van Doos' and the Great War," November 5, 2018, Canadian Encyclopedia.

6. Ibid.

7. "The First World War" by Sean Mills (under the direction of Brian Young, McGill University), McCord Museum website.

8. Claude Harb, "Le Droit et l'Outaouais pendant la Premi re Guerre mondiale," Bulletin de l'Institut Pierre Renouvin, Spring 2017 (No. 45), publisher: UMR Sirice.

Recruitment of Indigenous Peoples

When the First World War broke out on July 28, 1914, Canada had no official policy on the recruitment of Indigenous Peoples into the army because they did not have status as citizens. However, in 1915, as the casualties began to mount, the British government directed the Dominions to begin recruiting Indigenous people for the war effort. Australia and New Zealand, along with Canada, recruited Indigenous soldiers to fight on the side of British imperialism in the war. It is estimated that 4,000 Indigenous men and woman served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War out of a total of some 600,000 troops from Canada. It is estimated that a third of "Status Indian" men between the ages of 18 and 45 served in the War. There are no known statistics for Métis and Inuit because the Canadian government only recognized "Status Indians" in the records.

Many

First Nations, which were the main source of Indigenous

recruits along with a much smaller number of Métis and

Inuit, protested against the attempt to recruit them into the Canadian

colonial army and opposed the arrival of recruitment officers and the

Indian Agent on their reserves. Other

First Nations refused to participate unless they were accorded equal

status as sovereign nations and dealt with on a nation-to-nation basis

by the British Crown with which they had signed their treaties.

Many

First Nations, which were the main source of Indigenous

recruits along with a much smaller number of Métis and

Inuit, protested against the attempt to recruit them into the Canadian

colonial army and opposed the arrival of recruitment officers and the

Indian Agent on their reserves. Other

First Nations refused to participate unless they were accorded equal

status as sovereign nations and dealt with on a nation-to-nation basis

by the British Crown with which they had signed their treaties.

Some Indigenous leaders and elders also reminded the government that they had received reassurances at the time of the signing of the numbered treaties with the Crown that their youth would not be serving in any wars, specially those abroad.

As well, many Indigenous women wrote to the Department of Indian Affairs demanding that the Canadian government keep its hands off their sons and husbands and that they were needed at home.

Many reasons are given for the participation of Indigenous people in the First World War. One of the reasons was the promise of a regular paycheque, another was the argument that within the First Nations, warrior societies should play their role in assisting the Crown as their relations were with the Crown, not Canada. Another argument was that after making their contributions, Indigenous relations with the Canadian state would improve when they returned.

Indigenous soldiers took part in all the major battles that the Canadian army participated in and distinguished themselves as scouts, snipers, trackers and as front line fighters winning the admiration and respect of their non-Indigenous comrades and officers. At least 50 Indigenous soldiers were decorated for bravery and heroism. In the course of the war, some 300 lost their lives and many more were wounded and others died after returning home from the effects of mustard gas poisoning, wounds that they suffered, and diseases they had contracted in Europe such as tuberculosis and influenza.

The Military Service Act passed by the the Borden Conservative government in 1917 introduced conscription including for "Status Indians." Conscription was not only broadly opposed in Quebec, but also by Indigenous Peoples who denounced this manoeuvre by the government to disregard their status as Indigenous Peoples. In response to this opposition, the government was forced to grant Indigenous Peoples an exemption from serving overseas.

Other injustices were also imposed on Indigenous Peoples. In 1917, Arthur Meighen, Minister of the Interior as well as head of Indian Affairs, launched the "Greater Production Effort," a program intended to increase agricultural production. As part of this scheme, reserve lands that were considered "idle" were taken over by the federal government and handed over to non-Indigenous farmers for "proper use." After both non-Indigenous and First Nations protested that this was a violation of the Indian Act, the government amended the Indian Act in 1918 to make these illegal actions legal.

Post-War Brutality Against Indigenous Veterans

At the end of the war, returning soldiers, including Indigenous veterans, held high hopes that their contributions to the war effort would translate into a better future for themselves and their communities. Indigenous veterans thought that their status as "wards" of the state would be over and that they would be treated as equals. Instead they found that nothing had changed and the racism and colonial attitudes of the Canadian government remained intact.

Many Indigenous veterans returned with illnesses such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and influenza which they had contracted overseas. Those who had suffered poison gas attacks returned with weakened lungs and became more prone to tuberculosis and other respiratory illnesses. Like their non-Indigenous fellow soldiers, Indigenous veterans suffered from the trauma of the war -- which in today's terms would be called post-traumatic stress disorder -- and other illnesses such as alcoholism, which wrecked their lives and caused many problems for their families and communities. In fact, the overall standard of living in Indigenous communities declined in the years following the war as returning veterans found it extremely difficult to keep regular work and to return to their pre-war lives. In the face of these complex problems, Canada provided little support to Indigenous veterans.

Benefits and support for veterans from the Canadian government through the Soldiers Settlement Acts of 1917 and 1919, such as land and loans to encourage farming, did not extend to Indigenous veterans. To add insult to injury, through the Acts the federal government confiscated an additional 85,844 acres from reserves to provide farmland for non-Indigenous veterans.

The racist Canadian colonial state's aim of exterminating Indigenous Peoples by assimilating them was alive and well. This was expressed by the notorious Duncan Campbell Scott, architect of the Residential School System in Canada and Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, who wrote in a 1919 essay:

These men who have been broadened by contact with the outside world and its affairs, who have mingled with the men of other races, and who have witnessed the many wonders and advantages of civilization, will not be content to return to their old Indian mode of life. Each one of them will be a missionary of the spirit of progress... Thus the war will have hastened that day,... when all the quaint old customs, the weird and picturesque ceremonies... shall be as obsolete as the buffalo and the tomahawk, and the last tepee of the Northern wilds give place to a model farmhouse.

|

The neglect of Indigenous veterans and other abuses of Indigenous Peoples by the Canadian state, led Haudenosaunee veteran Frederick Loft, from Six Nations on the Grand River, who had served as a lieutenant overseas in the Forestry Corps, to form the League of Indians of Canada in 1919. Before his return to Canada, Loft had met with the King and Privy Council in London to express his concerns about the way Indigenous Peoples in Canada were being treated. Under his leadership, the League of Indians fought to protect the lands and treaty rights of Indigenous Peoples.

In particular, the League of Indians fought to preserve Indigenous rights and led the battle against the "involuntary enfranchisement" changes to the Indian Act, orchestrated by Duncan Campbell Scott and passed in 1920, aimed at extinguishing Indigenous title by giving "Status Indians" the vote, while at the same time working to undermine and sabotage the work of the League of Indians and isolating and criminalizing Loft. The League also mounted legal challenges to establish Indigenous claims to hunting, fishing and trapping rights among other things.

The League of Indians was the first attempt by Indigenous Peoples in Canada to form a national organization to resist the Canadian colonial state's assault on their rights and claims. It subsequently inspired the formation of other Indigenous political organizations to battle the colonial Canadian state and its racist policies.

(With files from Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Canadian Encyclopedia, Veterans Affairs Canada and Library and Archives Canada.)

Black Construction Battalion

While Black people were used by the British colonialists as cannon fodder to suppress the struggles for rights of others, their own legitimate rights and claims were marginalized and denied.

When

the First World War broke out, Black men in Nova Scotia and

other places who tried to enlist faced racist obstacles and

justifications to keep them out. The Chief of the General Staff of the

Canadian Army at the time asked in a memo: "Would Canadian Negroes make

good fighting men? I do not

think so." When a group of about 50 Black Canadians from Sydney, Nova

Scotia, tried to enlist they were advised, "[T]his is not for you

fellows. This is a white man's war."

When

the First World War broke out, Black men in Nova Scotia and

other places who tried to enlist faced racist obstacles and

justifications to keep them out. The Chief of the General Staff of the

Canadian Army at the time asked in a memo: "Would Canadian Negroes make

good fighting men? I do not

think so." When a group of about 50 Black Canadians from Sydney, Nova

Scotia, tried to enlist they were advised, "[T]his is not for you

fellows. This is a white man's war."

In the face of repeated opposition to this state racism and discrimination, the Canadian government permitted the formation of No. 2 Construction Battalion (also known as the Black Battalion), based in Pictou, Nova Scotia. It was a segregated battalion that never saw military action because they were not permitted to carry weapons. Five hundred Black soldiers volunteered from Nova Scotia alone, representing 56 per cent of the Black Battalion. It was the only Black battalion in Canadian military history.

The Battalion was sent to eastern France armed with picks and shovels to dig ditches and construct trenches at the front, putting themselves in grave danger. They also worked on road and rail construction. Following the end of the War in 1918, the members of the Battalion were repatriated and the unit was disbanded in 1920.

According to Veterans Affairs Canada, another some 2,000 Black Canadians served on the front lines of World War I through other units, some with the armies of other countries.

Once returned, the Black veterans of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, and other returning Black veterans found that nothing had changed at home and they continued to face racism and discrimination in employment, veterans' benefits, and other social services.[1]

Note

1. The Canadian state likes to portray the participation of Black people in the Canadian military in the most self-serving manner. Veterans Affairs Canada notes, "The tradition of military service by Black Canadians goes back long before Confederation. Indeed, many Black Canadians can trace their family roots to Loyalists who emigrated North in the 1780s after the American Revolutionary War. American slaves had been offered freedom and land if they agreed to fight in the British cause and thousands seized this opportunity to build a new life in British North America."

A rosy picture, but far from reality. The enslaved people that ended up on the side of the British colonialists during the U.S. War of Independence, numbering some 30,000, served as soldiers, labourers and cooks. When the British were defeated, the British evacuated some 2,000 of these "Black Loyalists" to Nova Scotia with the promise of a better life and opportunities as free people. Others were thrown to the four winds landing on the Caribbean Islands, in Quebec, Ontario, England and even Germany and Belgium. Those the British outright abandoned in the U.S. were recaptured as slaves.

Many of the Black Loyalists landed at Shelburne, in southeastern Nova Scotia, and later created their own community nearby in Birchtown, the largest Black settlement outside Africa at the time. Other Black Loyalists settled in various places around Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Far from finding freedom, and new opportunities, most of the Black Loyalists never received the land or provisions that they were promised and were forced to make their living as cheap labour -- as farm hands, day labourers in the towns or as domestics. In 1791, in order to solve the "Black problem," the British Colonial authorities repatriated about half of these Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to Sierra Leone, Africa where the British wanted to found a colony and used the Black Loyalists to face the dangers, many of them dying in the process.

Those Black people who remained were used by the British colonial state in the War of 1812 to fight the Americans. Black people in Ontario and also from other places were part of a colonial militia called in to suppress the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837.

(With files from Veterans Affairs, CBC and the Canadian Encyclopedia.)

The Case of Ginger Goodwin

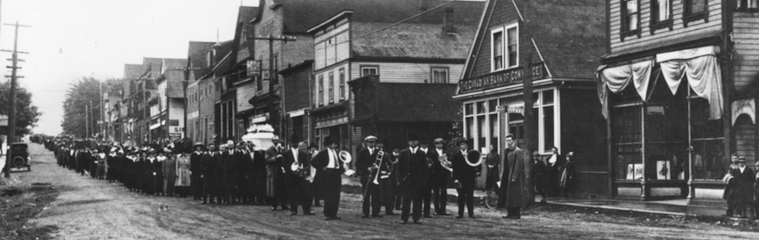

Twenty-four hour

Vancouver General

Strike was held to coincide with Ginger Goodwin's funeral,

Twenty-four hour

Vancouver General

Strike was held to coincide with Ginger Goodwin's funeral,

August

2,

1918.

Ginger (Albert) Goodwin was a coal miner from England who immigrated to Canada in the early 20th century. He worked in coal mines in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia and Michel, British Columbia before settling in Cumberland on Vancouver Island in 1910 or early 1911. He worked in the Dunsmuir coal mine in Cumberland and participated in the strike of 1912 to 1914. He was active in the United Mine Workers of America and in 1914 became an organizer for the Socialist Party.

In

1916 he moved to Trail in the interior of BC where he

worked for some months as a smelterman for the Consolidated Mining and

Smelting Company of Canada Limited. He was the Socialist Party of

Canada's candidate in Trail in the provincial election of 1916, coming

in third, and in December of

that year was elected full-time secretary of the Trail Mill and

Smeltermen's Union, a local of the International Union of Mine, Mill

and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW). The following year he was elected as

vice-president of the BC Federation of Labour, president of IUMMSW's

District 6 and president of the

Trail Trades and Labour Council. He was proposed by the union as deputy

minister of BC's newly founded Department of Labour, but not selected.

This was a proposal supported by the trades and labour councils of both

Victoria and Vancouver.

In

1916 he moved to Trail in the interior of BC where he

worked for some months as a smelterman for the Consolidated Mining and

Smelting Company of Canada Limited. He was the Socialist Party of

Canada's candidate in Trail in the provincial election of 1916, coming

in third, and in December of

that year was elected full-time secretary of the Trail Mill and

Smeltermen's Union, a local of the International Union of Mine, Mill

and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW). The following year he was elected as

vice-president of the BC Federation of Labour, president of IUMMSW's

District 6 and president of the

Trail Trades and Labour Council. He was proposed by the union as deputy

minister of BC's newly founded Department of Labour, but not selected.

This was a proposal supported by the trades and labour councils of both

Victoria and Vancouver.

Ginger Goodwin opposed World War I for political reasons on the grounds that workers should not kill each other in economic wars. "War is simply part of the process of Capitalism. Big financial interests are playing the game. They'll reap the victory, no matter how the war ends," he said. Nonetheless, he registered for conscription as the law required and was classified as unfit. However, not two weeks following the start of a strike in Trail for the eight-hour day, which Goodwin led, he was ordered to undergo a medical re-examination and this time was classified as fit to serve.

His appeal against conscription was rejected in April 1918. Ordered to report to army barracks he refused to compromise his conscience and hid out with others resisting conscription in the hills near Cumberland where people from the town ensured they had food and supplies.

Goodwin was shot and killed on July 27, 1918 by Constable Dan Campbell of the Dominion Police, one of three members of a team that was hunting men who were evading the Military Service Act. The anger of the people of Cumberland and workers throughout the province was such that on August 2, 1918 there was a mile-long funeral procession in Cumberland, and BC's first general strike the same day in Vancouver.

Ginger Goodwin's funeral,

Cumberland BC,

August 2, 1918.

Ginger Goodwin's funeral,

Cumberland BC,

August 2, 1918.

On June 24, 2018 in honour of Ginger Goodwin, labour martyr and war resister, on the 100th anniversary of his death, the Cumberland Museum along with the BC Federation of Labour and local unions, artists, musicians and actors, re-enacted the funeral procession as part of the annual Miner's Memorial events held from June 22 to 24. On July 23, 2018, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Goodwin's death, the BC government erected a monument at nearby Union Bay, the coal port that served the Cumberland mines, in honour of Ginger Goodwin for his fight for workers' rights and his opposition to conscription. A section of highway near Cumberland was named "Ginger Goodwin Way" in 1996 in his honour.

Britain

British Movement of Conscientious Objectors:

The Men Who Said

No

In the early 20th century, the concern of working people in many countries about the danger of an inter-imperialist war for the redivision of the world was profound. Britain was no exception.

Long before the outbreak of World War I, thousands of people campaigned against the escalating signs of war and, finally, against the inter-imperialist war itself. Enormous pressure was put on the people to join the war in the name of high ideals of patriotism and loyalty to the British Empire. This made enemies out of those who did not espouse these values. The same was the case throughout the British Commonwealth, including Canada. Working people's resistance to war took many forms, including conscientious objection.

The articles below highlight the organized movement of conscientious objectors in Britain, the men who courageously stood with their anti-war conscience in the face of threats, bullying, imprisonment and death. They said No! and many, including a militant women's movement, rallied to their just stand.

(With files from menwhosaidno.org, UK Parliament website)

Opposition in Britain to

the War and

Criminalization of Conscience

Anti-conscription demonstration in

London, January 1916.

Anti-conscription demonstration in

London, January 1916.

Conscription was widely unpopular in Britain. Trade unions, political parties and religious groups were all vocal in their opposition to its introduction but nonetheless, with ever-rising deaths and casualties, volunteer numbers had shrunk to a trickle despite the pressure on boys and men to go to war and the pressure for conscription intensified. By June 1915 supporters of conscription began to gain wider support and for the first time in British history, politicians began to seriously debate forcing millions of men against their will into the armed forces. Debates raged across the country. Trade unions lobbied against it; Members of Parliament (MPs) resigned over it.

On January 5, 1916, Britain passed the Military Service Act, which imposed conscription on all single men aged between 18 and 41, but exempted the medically unfit, clergymen, teachers and certain classes of industrial workers. A second act passed in May 1916 extended conscription to married men. Still later in 1918, the Military Service (No. 2) Act raised the age limit for conscripts to 51.

|

|

Besides this, once Britain officially declared war on August 4, 1914, the draconian Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed on August 8, 1914 which made active opposition to the war a criminal offence. DORA gave the government the power to suppress the activities of the anti-war movement and to attack the right to speak and to publish. Several leading anti-war activists, including the Scottish teacher and revolutionary John Maclean, were arrested and imprisoned as a consequence.

Despite this criminalization of dissent, opposition to the war and the government's policy of forced conscription was widespread. In April 1916, more than 200,000 people demonstrated in Trafalgar Square in London against conscription. Between May 1916 and the armistice in November 1918 in Britain some 20,000 men refused to be conscripted into the British army. Several thousand of them were imprisoned for their stand. Many felt that it was wrong to kill under any circumstance and that war was not the solution to any problem.

Besides the attempt to suppress the anti-war movement through DORA, with the conscription regime in place, from the moment men received the letters demanding they present themselves at a military depot, they were deemed to be soldiers and subject to military law. This stripped men of their civil liberties, negated their right to conscience and gave the army total control over their lives for an indefinite period.

Courageous Resistance in the Face of Draconian Military Justice

With conscription in place, some 2,000

Military Service Tribunals were set up around Britain to question men

who sought to be exempted. Applicants had to fill in questionnaires

making their case. Exemptions could be given for a number of reasons

including conscientious objection -- on

domestic grounds (people with ill-health, unsupported children or

elderly relatives), or because they had important civilian jobs, such

as doctors, teachers, farmers and key industrial workers. Millions

applied for some kind of exemption and with this huge number of cases,

Tribunal hearings would

usually spend only a few minutes on each applicant before Tribunal

members made their decision. Overall, of those who applied for

exemptions, some 800,000 applied for Conscientious Objector (CO)

status, and only 16,000 or two

per cent of them were officially granted this status.

The Tribunals were appointed by the local municipal council, typically about 25 men, rarely any women, with five to six being present for the actual hearings. Although they were supposed to be impartial, nepotism in the appointments was typical. Furthermore, many Tribunal members were biased against COs and the ever present military representative made sure there was no backsliding by other members. The military need for fighting men at the front was held to be paramount.

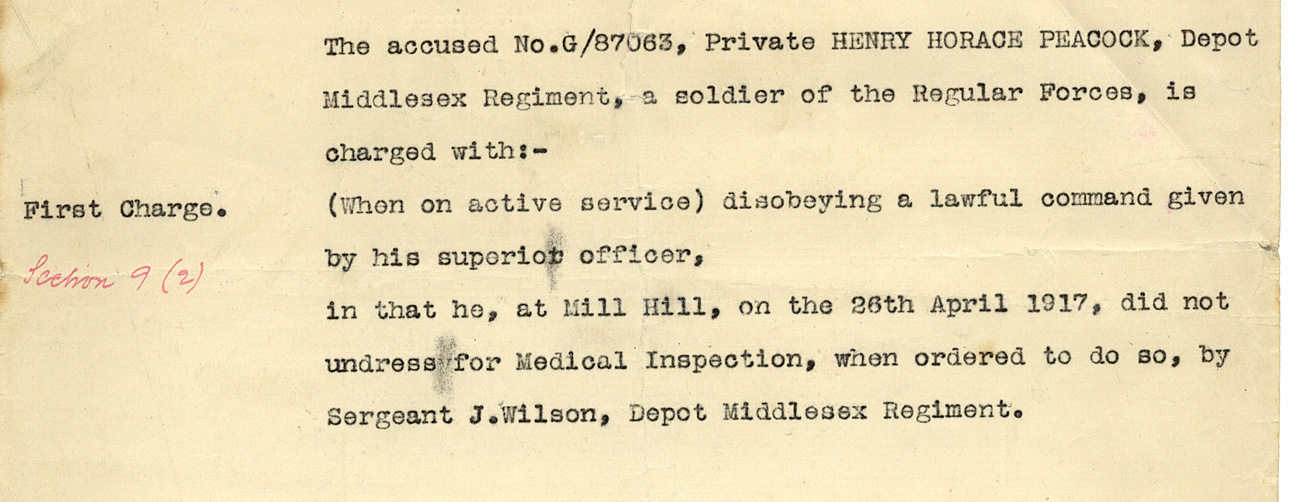

Although the Military

Service Act included a hard fought for

but ill-defined clause on conscientious objection, many Tribunals

simply did not understand they could grant absolute exemptions from

military service (with no conditions) for COs and they often saw their

role as making sure as many men

as possible were enlisted into the army. As a result, thousands of COs

were treated unfairly and many of them would suffer harsh treatment in

prison.

Death Sentences

In the early days of conscription, the army had no idea how to deal with stubborn, principled men who refused to obey any orders. Bullying and intimidation had failed and in May 1916, the army stepped up its threat when it shipped 50 COs from around Britain to France and sentenced 35 of them to death.

Assurances had previously been given that COs would not be subjected to the death penalty but the position of men who had been rejected by the Tribunal and sent to the Army as insincere in their objection was unclear. Did this mean that they were subject to army regulations, which prescribed death by shooting as punishment for disobedience on active service? No one knew.

Soon after the introduction of conscription, rumours about COs being sent to France to be shot began to circulate. "If they disobey orders of course they will be shot, and quite right too!" said Lord Derby, Director of Recruiting, as 17 men in Landguard Fort were released from their shackles on May 7 and put on a train to France.

On being told of this, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith immediately dispatched a message to the front forbidding any execution without the knowledge of the Cabinet or sending any further COs to France, but the army had ideas of its own. While the government was publicly denying that COs had been sent to France to be shot, the army, in a show of disregard of the elected civil authorities, dispatched a further batch of men to France who were told that they were going to be shot. They were marched to the train to the sound of the military band playing the "Death March."

By moving these COs to France and closer to the front line the army believed it could intimidate them into submission. It would give the army the pretext to say that the COs had failed "under active service conditions" and it would be free to summarily execute those who continued to "disobey orders."

After weeks of painful punishments and constant abuse, the COs -- now known as "The Frenchmen" -- were formally told: Continue to disobey and face the death penalty. By June, the Army was running out of patience. The Frenchmen were marched out in groups to a camp outside Boulogne within sight of the cliffs of Dover across the English Channel and told for a final time to obey orders. When they once again refused, their sentence was read out.

One of the COs, Hubert Peet, later recalled, "I was number three on the list, and as I stepped forward I caught a glimpse of my paper as it was handed to the Adjutant. Printed at the top in large red letters, and doubly underlined, was the word 'Death.' I can hardly analyze the feeling that flashed through my mind as I caught sight of the word.'

"'The sentence of the court is to suffer death by being shot,' said the Adjutant. 'This sentence has been confirmed by the Commander in Chief' -- there was a long pause -- 'and commuted to ten years penal servitude.'"

All the COs were given the same long sentence, but they had escaped the death penalty and were sent back to civilian prisons in Britain. At the last moment, political pressure and frantic work at home by their supporters had saved their lives. The resolve and determination of the threatened COs became a rallying point for those in Britain and made it clear that their resistance would not be broken by military means.

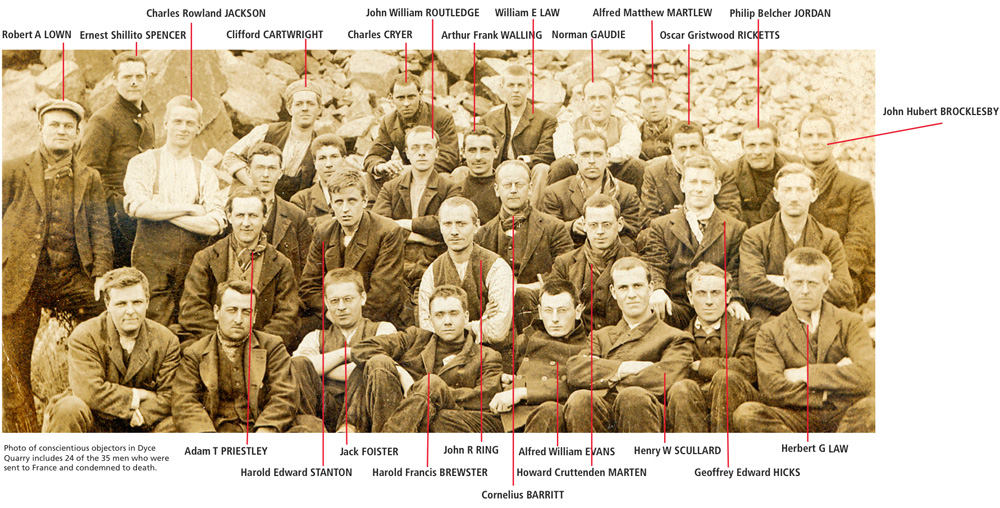

Image of conscientious objectors in

Dyce

Quarry. Includes 24 of the 35 men who were sent to France and sentenced

to death. Image from Refusing to Kill exhibition.

Image of conscientious objectors in

Dyce

Quarry. Includes 24 of the 35 men who were sent to France and sentenced

to death. Image from Refusing to Kill exhibition.

(menwhosaidno.org, UK Parliament website)

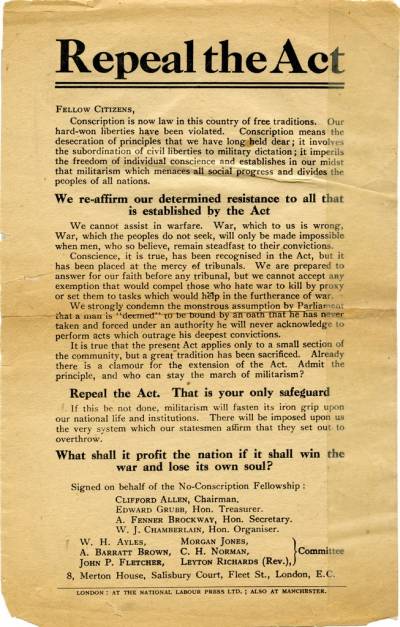

Organizing to Oppose Conscription and Defend Conscientious Objectors

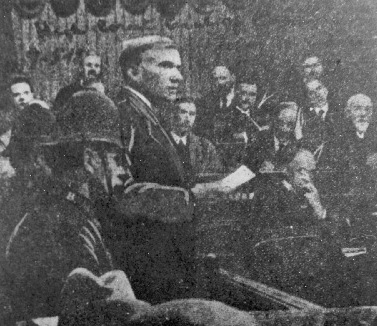

Members of No Conscription

Fellowship national committee on their way to prison, July 1916.

Members of No Conscription

Fellowship national committee on their way to prison, July 1916.

The No Conscription Fellowship (NCF) was formed to campaign against the imposition of compulsory conscription. Later, when this failed and conscription became law, the NCF provided support for conscientious objectors (COs) throughout Britain. As time went by, what stands to take in the various circumstances to affirm one's conscience required ongoing deliberation in the anti-conscription movement. The NCF provided a vital forum and converging point for COs and their defenders.