The Temporary Foreign Worker Program

- Pierre Chenier -

The

fastest

growing

category

of

migrant

workers

in

Canada,

as

is

the

case

worldwide,

is

the

undocumented

worker.

Studies

and

statistics

regarding

these

workers

are

rare. One study in 2011, funded by the Canadian

Institutes of Health Research, estimated that between 200,000 and

500,000 undocumented workers live in Canada. They are concentrated in

Ontario, where they are employed mainly in construction, hospitality

and agriculture.

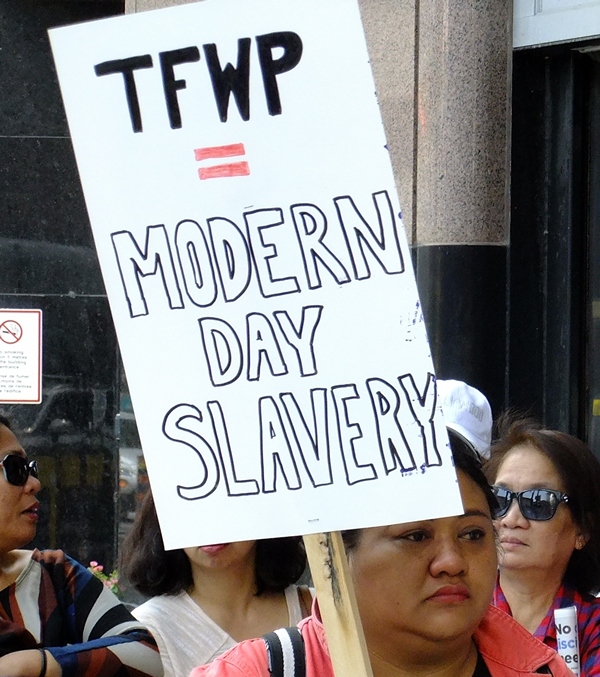

The study also

showed that many of the undocumented workers began their work in Canada

as "documented workers," including through the Temporary Foreign Worker

Program (TFWP), and had become undocumented because of the conditions

of

servitude and arbitrariness that are the trademark of this program.

Among other things, many temporary foreign workers whose employment

contract with an employer is broken, whether through the employer

terminating the contract or the worker leaving the particular job due

to untenable conditions, remain in Canada as undocumented workers. The study also

showed that many of the undocumented workers began their work in Canada

as "documented workers," including through the Temporary Foreign Worker

Program (TFWP), and had become undocumented because of the conditions

of

servitude and arbitrariness that are the trademark of this program.

Among other things, many temporary foreign workers whose employment

contract with an employer is broken, whether through the employer

terminating the contract or the worker leaving the particular job due

to untenable conditions, remain in Canada as undocumented workers.

Various

governments

present

the

situation

facing

temporary

foreign

workers

as

one

governed

by

rules,

unlike

that

of

undocumented

workers.

They

say,

for

example,

that

temporary

foreign workers are covered by federal and

provincial minimum labour standards laws, have access to many social

programs and public services, and have a path to permanent residence,

while undocumented workers, although working, are considered outside

those laws and are criminalized as outlaws in a vulnerable state of

lawlessness.

The

objective

conditions

of

servitude

in

which

undocumented

workers

work

are

such

that

there

are

few

official

rules

in

force

regarding

their

employment

and

living

conditions, with most left to the dictate of the

employer. This vulnerability to arbitrary dictate includes even

documented workers within the narrow confines of the TFWP and

associated programs. Their rights are subject to

abuse, including their fundamental right to be equal members of the

polity without living under constant threat of being deported.

The

situation

for

foreign

workers

is

marked

by

the

arbitrariness

of

employers

in

Canada

and

the

agencies,

both

Canadian

and

foreign,

that

recruit

them

in

their country. Governments keep foreign workers in a

vulnerable position and open to abuse by refusing to abolish their

temporary status. Without their rights guaranteed, their dignity as

workers is denied and their precarious status is maintained.

Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP)

The

federal

TFWP

includes

two

subprograms:

Live-in

Caregiver

Program

and

the

Seasonal

Agricultural

Worker

Program.

A

range

of

other

workers

also

belong

to

the

general category of temporary foreign

workers. The TFWP and the International Mobility Program (IMP) were one

program until the Harper Government made the IMP a separate program in

2014.

Labour Market Opinion

Research

conducted

by

the

Economics,

Resources

and

International

Affairs

Division

of

the

Canadian

government

found

that

on

December

1,

2013,

there

were

386,406

temporary

foreign

workers in Canada. Of these,

126,816 were subject to a labour market opinion, and 259,590 were not

subject to a labour market opinion.

Employers who want

to recruit temporary foreign workers in general must submit a Labour

Market Impact Assessment (LMIA),

while employers who want to recruit through the IMP do not have to do

this. The requirement for an LMIA is based on the charade that the TFWP

is strictly intended to temporarily fill positions for which no

Canadian citizen or permanent resident is available. This is a charade

because foreign workers have been coming to Canada for decades to

occupy positions in many sectors, such as agriculture, live-in

caregivers,

hospitality and food processing. The positions are not

and never have been temporary, only the workers that fill those

permanent positions are temporary. Their temporary status is an

instrument to keep them vulnerable, in the lowest paid jobs, in the

worst conditions and with their rights denied, and puts downward

pressure on

wages generally. Employers who want

to recruit temporary foreign workers in general must submit a Labour

Market Impact Assessment (LMIA),

while employers who want to recruit through the IMP do not have to do

this. The requirement for an LMIA is based on the charade that the TFWP

is strictly intended to temporarily fill positions for which no

Canadian citizen or permanent resident is available. This is a charade

because foreign workers have been coming to Canada for decades to

occupy positions in many sectors, such as agriculture, live-in

caregivers,

hospitality and food processing. The positions are not

and never have been temporary, only the workers that fill those

permanent positions are temporary. Their temporary status is an

instrument to keep them vulnerable, in the lowest paid jobs, in the

worst conditions and with their rights denied, and puts downward

pressure on

wages generally.

Employers

who

recruit

workers

through

the

IMP

do

not

require

an

LMIA

because

the

program,

according

to

official

propaganda,

is

intended

to

provide

greater

competitive

advantages

to Canada economically, culturally or otherwise.

This includes, among other things, the mobility of labour under free

trade agreements. The IMP, unlike the TFWP,

includes an open work permit that does not bind the participant to a

single employer. It also offers an easier route to permanent residence

status precisely because it is seen as beneficial to Canada's

competitiveness to keep those particular workers in the country.

Temporary

foreign

workers

requiring

an

LMIA

are

contractually

bound

to

a

sole

employer

under

conditions

similar

to

indentured

labour.

The

contracted

condition

makes

it

difficult

to leave an abusive employer or dangerous

job without being subjected to immediate removal from the country

because when the contract is broken the worker no longer has a legal

status under the rules of the LMIA.

Workers

under

an

LMIA

contract

are

vulnerable

because

if

they

complain,

the

job

may

be

terminated

by

the

employer,

meaning

they

must

leave

the

country.

The action may well be done in silence because the workers are so

vulnerable, with limited legal recourse. Dismissed workers must go

through a new LMIA process, which takes months and is not assured, or

return to their country, or become undocumented workers. To change

employers, the worker must receive a new job offer from a potential

employer, and have an LMIA approved. This takes between three and five

months but that is not the end of the process. The worker must then

apply for a new work permit, which adds between three and six months.

During this long period, the worker is not eligible to work or receive

employment insurance or social assistance so may end up without income

for many months. Remembering that these workers generally receive the

lowest pay while working, the reality of their lack of income pushes

many either into returning home or becoming undocumented workers.

Without Rights Guaranteed, Workers Are Vulnerable

The

rule

of

law

must

apply

equally

to

all

without

denial

of

rights

to

some

and

privilege

to

others.

A

basic

human

right

is

not to be considered

temporary or illegal and subject to deportation or other arbitrary

measures of a police power. The entire concept of temporary worker

should be considered ultra vires

(outside the law) and without validity

within a rule of law based on a modern constitution that applies

equally to all human beings without prejudice or privilege.

Examples abound of a

contradiction between the actual conditions of temporary, migrant and

refugee workers and the liberal democratic propaganda that says in

words that all humans are equal and protected by a rule of law that

applies to all without prejudice or privilege. Examples abound of a

contradiction between the actual conditions of temporary, migrant and

refugee workers and the liberal democratic propaganda that says in

words that all humans are equal and protected by a rule of law that

applies to all without prejudice or privilege.

The

status

of

temporary

for

workers

selling

their

capacity

to

work

to

an

employer

accords,

in

practice,

arbitrary

power

and

privilege

to

the

employer

and

subservience or voluntary servitude to the employees.

Liberal democratic law and constitutions uphold this inequality and

privilege through the accordance of superior rights to property, wealth

and social status over the rights that people have by virtue of being

human.

Many

temporary

workers

live

in

employer

provided

or

controlled

housing.

This

arrangement

gives

employers

substantial

control

over

workers'

food,

space,

sleep

and

social

networks.

Workers

can be subject to

intimidation and this situation reinforces the total imbalance of power

between the employer and worker. Often no clear boundary exists between

being on-duty and off-duty.

Examples

abound

of

abuse

by

recruitment

agencies,

both

public

and

private,

and

individual

recruiters

that

have

become

a

global

system

of

human

trafficking.

The

abuses

include the charging of exorbitant fees, false

claims and forged documents. Recruiters and employers often persuade

workers to take loans from them and subsequently add

interest and other charges for services or penalties for breaking

arbitrary rules.

Charged

large

fees,

workers

are

sometimes

issued

incomplete

or

blatantly

fake

documents,

given

false

names

of

employers

or

non-existent

jobs.

In

recent

years,

"release

upon

arrival" schemes have become more frequent.

These are schemes where workers have no employer although names are on

their papers or contracts. The workers are "released" from the phony

contract upon arrival at the airport or recruiter's office in Canada.

Sometimes such a scheme is openly offered to workers who are assured

that it will be easy to find a real employer once in Canada. In many

cases, the recruiters also keep such "released" workers in a workplace

owned or arranged by the recruiter where they have to work for room and

board while waiting for an employer who will hire them.

Temporary

foreign

workers

pay

income

tax

and

sales

tax

and

contribute

to

the

Canada

Pension

Plan

and

the

Employment

Insurance

(EI)

regime.

However,

they

are

not entitled to regular EI benefits for their periods of

unemployment once their employment contract is terminated. Officially,

they are entitled to other EI benefits, such as parental or maternity

benefits, but these become almost impossible for them to access once

their official employment contract is terminated.

Temporary

foreign

workers

are

supposed

to

be

covered

by

minimum

labour

standards

and

occupational

health

and

safety

laws,

but

enforcement

is

an

issue.

Their

vulnerable

status makes it very difficult for them to insist that

the employer respect the existing laws or to call upon the government

to provide redress and official enforcement is reported to be unseen.

In

theory,

temporary

foreign

workers

have

the

right

to

permanent

residence

status

but

no

path

to

status

exists

within

the

program.

They

can

acquire

sponsorship

from their employer, but usually the employer has

no incentive to do so. The applicant must master an official language

but usually their working conditions, including long hours without

structured breaks, prohibit them from attending classes, if they exist

in their region, or regularly fraternizing with English or French

speakers through organized social or sports events.

The Live-in

Caregiver Program does include a route to permanent residence, but

caregivers, the vast majority of them women, are subject to a two-step

immigration process that requires they enter Canada with temporary

status and an employment contract but without their families. They must

complete their contract before they can apply for permanent residence,

which presents problems of what to do after the contract finishes. The

program for permanent residence also includes a cap on applications,

which is yet another restriction. This year, after sustained work by

live-in caregivers and their supporters, the federal government

announced two "pilot projects" to run over the next five years, that

will allow those recruited in this category of workers to come to

Canada with their families. Once a caregiver has their work permit and

two years of experience, it is said they will then have "access to a

direct pathway to permanent residence." As well, a small window is

presently open this year to retroactively provide such "access" for

caregivers already in Canada who came to the country with the

expectation that they could apply for permanent residency, only to find

out later that this was not possible under the programs through which

they were recruited. The Live-in

Caregiver Program does include a route to permanent residence, but

caregivers, the vast majority of them women, are subject to a two-step

immigration process that requires they enter Canada with temporary

status and an employment contract but without their families. They must

complete their contract before they can apply for permanent residence,

which presents problems of what to do after the contract finishes. The

program for permanent residence also includes a cap on applications,

which is yet another restriction. This year, after sustained work by

live-in caregivers and their supporters, the federal government

announced two "pilot projects" to run over the next five years, that

will allow those recruited in this category of workers to come to

Canada with their families. Once a caregiver has their work permit and

two years of experience, it is said they will then have "access to a

direct pathway to permanent residence." As well, a small window is

presently open this year to retroactively provide such "access" for

caregivers already in Canada who came to the country with the

expectation that they could apply for permanent residency, only to find

out later that this was not possible under the programs through which

they were recruited.

In

2014,

in

the

midst

of

mass

media

coverage

of

certain

employers

abusing

the

TFWP,

the

Harper

government

intervened

in

such

a

manner

to

create

friction between Canadian workers and temporary workers. The government

made a big deal of giving Canadian workers priority over temporary

workers for available jobs. In the process, the government made the

eligibility criteria for employment insurance even more stringent for

all workers and further limited foreign workers' access to any EI

benefits. A goal of all these programs, aside from providing cheap

workers for employers, is to discourage unity of the working class in

defence of its rights.

The

federal

government

gradually

reduced

the

percentage

of

eligible

foreign

workers

relative

to

a

company's

total

workforce

to

10

per

cent

by

2016.

According

to

the workers' defence organizations, as the percentage was

lowered some temporary foreign workers who had arrived when the

percentage was higher were suddenly fired and forced to work

underground to stay in Canada. In response to the lower allowable

percentage, certain regular employers of temporary workers campaigned

to have the percentage relaxed. The Trudeau government complied,

raising

the level to 20 per cent, a figure that still retains its arbitrariness

as far as temporary workers are concerned as they become disposable

when the percentage is exceeded.

The

Harper

government

in

2014

also

changed

the

rules

so

that

the

federal

government

may

refuse

applications

for

the

hiring

of

temporary

foreign

workers

for

low-paid positions in the accommodation and food services

and retail trade sectors in areas where the official unemployment rate

is equal to or higher than six per cent. The Trudeau government has

endorsed the change. Again, this pits workers against one another in

that foreign workers are indirectly blamed for causing hardship for

Canadian workers as competitors willing to accept low wages and

precarious work. This perpetuates the imperialist consciousness that

obfuscates the class conflict between the working class and a ruling

financial oligarchy as the root of all the problems facing workers and

the socialized economy, and why workers are routinely deprived of their

rights and the economy suffers recurring crises and its basic problems

remain unsolved.

This article was published in

Volume 49 Number

15 - April 27, 2019

Article Link:

The

Temporary Foreign Worker Program

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca

|