|

October 29, 2016 - No. 42 Supplement

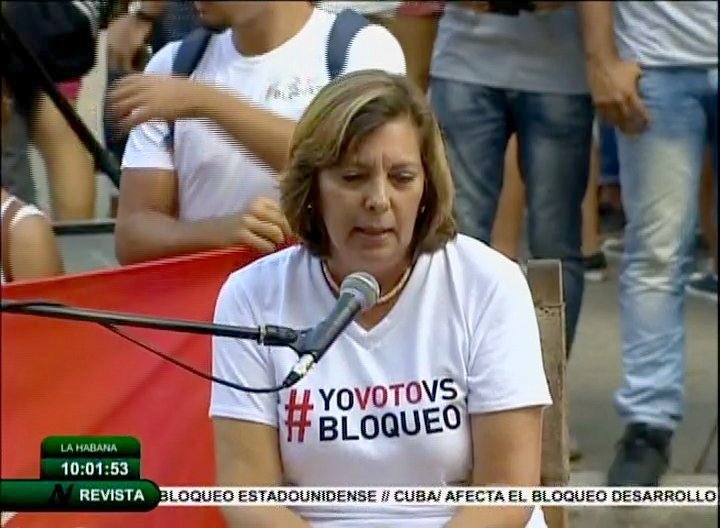

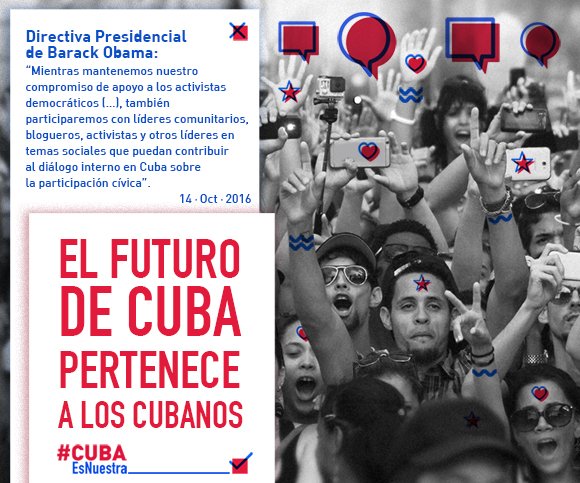

On October 17, Josefina Vidal, director general for the United States at Cuba's Ministry of Foreign Relations (MINREX) spoke and exchanged with Cuban youth and students on Cuba-U.S. relations during an event against the blockade at the University of Havana. TML Weekly is publishing the transcript below. ***Good morning everyone. Thank you all very much for the invitation, to add my voice to those of young people gathered here, and the people of Cuba, as I have already done online, on social media, to the 'Cuba votes against the blockade' event; because the blockade harms the Cuban people, damages Cuba as a whole, damages the functioning of our economy, damages Cuba's relations with third countries and those of third countries with Cuba, and even damages the relations we could have with the United States itself. For all these reasons we will vote against the blockade, and those who have not, still have the chance to on the "Cuba contra el bloqueo" website [www.cubavsbloqueo.cu]. Before having a conversation -- as I understand that this is a conversation with you and that I will take questions from you, I do not want this to be a monologue -- I would like to share a few introductory thoughts -- I will not be very extensive in my introduction -- considering that just three days ago, there were announcements made in the United States related to Cuba, there were two announcements: first, a presidential policy directive, entitled 'United States-Cuba Normalization' and secondly, the fifth package of measures to modify the application of certain aspects of the blockade. Firstly, I would like to refer to the presidential policy directive on Cuba. It is the first directive on Cuba approved and issued by President Obama who, as you know, is set to leave office in a few months, on January 20, 2017 to be exact, when a new administration, resulting from the elections to be held on November 8, will assume the leadership of that country, that is to say very soon. As I told some media outlets that we quickly called to MINREX last Friday, to provide our first reactions to the announcement of this directive, and I repeat today, we believe that this document is a significant step in the process toward lifting the blockade and to improving relations with Cuba. This is the second time a U.S. President has issued a directive providing instructions to the various branches of the federal government to initiate and conduct a process leading toward the normalization of relations with Cuba. The first to do so was President Carter in 1977, I have here a copy of the original document. This was his directive [points] indicating exploratory steps for the normalization of relations with Cuba; it was a secret document until 2002, when he asked his library to declassify it and brought it to Cuba and gave it to us in the context of his visit to our country at that time. It was a simple, brief directive, just one and a half pages and, as you know, given what happened in the history of relations with Cuba, nothing came of it, and it was not possible during his Presidency to advance toward the normalization of the relations. Now President Obama has issued a slightly longer document, its translation into Spanish has 15 pages, on which I want to offer my observations. This document issued by Obama establishes a guide for developing a process that in the future should lead to the normalization of relations. But keep in mind that what is reflected in this document comes from the perspective of the U.S. government, and therefore the document itself is not free of the interventionist vision that has historically marked the plans of the United States toward Cuba. I would like to make a brief analysis of its content, and for this I will refer, initially, to what we believe are some positive elements that appear in this directive. First, it is an attempt, which must be recognized, to try to ensure the future continuity of the current policy, which commenced on December 17, 2014, but only if a future president of the United States decides to follow that course. It is a policy of this Presidency and there is no obligation to follow it to the letter by future U.S. governments; perhaps some will, perhaps others not, maybe in part, maybe they will simply revoke it and issue a totally different directive. Nonetheless, we must recognize that it is a step in the right direction, leaving a guide that could be useful in a scenario in which a future President of that country wants to continue this policy. The document -- and we believe this is the first time, according to our studies over many years -- for the first time an official document of the United States government includes recognition of the independence, sovereignty, and self-determination of Cuba, which we, ever since reestablishing relations with this country, believe should be, and must remain, the essential principles on which to develop our ties going forward. There is also recognition in this directive, again for the first time, of the legitimacy of the Cuban government. One must understand that the policy of the United States for over 55 years included, in every aspect, the absolute non-recognition of the government of Cuba as a legitimate interlocutor; at all times Cuba's legitimacy was denied, and that was a hallmark of all policies followed over more than five decades. Well, in this directive the recognition of the government of Cuba appears as a valid, serious, legitimate interlocutor and equal to the U.S. government and, in turn, there is a recognition of the benefits that achieving a relationship of civilized coexistence would produce for both countries and both peoples, within the great differences that exist and, of course, will continue to exist in the future. And in particular the directive resolves to continue developing ties with the Cuban government and cooperation in areas of mutual interest. And it reiterates, something President Obama has said on other occasions, that the blockade is obsolete and must be lifted, and once again urges the United States Congress to work in that direction. However, up to here the essential components, we believe, have a favourable nuance to their treatment within the directive. But at the same time, there is a group of elements that have an interventionist trait. The directive does not hide, and from its opening paragraphs this is visible, that the objective of U.S. policy is to advance the interests of that country in Cuba, which is to promote changes in the political, economic and social order of our country. In turn, it reflects a marked interest in the development of the private sector in Cuba -- we know why they emphasize this -- and fundamentally questions the political system with which we Cubans have equipped ourselves. It does not renounce, in fact it recognizes that the

use of

old instruments of past policy, the policy of hostility toward

Cuba, will continue in the future, and mentions in particular

that the illegal radio and television broadcasts against Cuba

will continue; the programs they [the U.S.] claim are aimed to

"promote democracy" in Cuba and are of a subversive nature that

aim to promote changes in our country will continue, and the

intention remains to involve a wide range of Cuban society in the

implementation of these programs.

Finally, something which is very important -- it is not the last thing said, but it's the last thought I share with you -- it clearly states that the United States does not intend to modify the treaty that resulted in the occupation of a portion of Cuban territory by the Guantánamo Naval Base. In short, as conclusive elements of the analysis we have conducted on the presidential policy directive for the normalization of relations with Cuba: It establishes a new policy based on the recognition that the previous failed. But, how did it fail? Well, it clearly states that it failed to achieve changes in Cuba that respond to the interests of the United States. Therefore, there is a change in policy, it is confirmed that there is a modification to policy, but not to the strategic objective that this policy will continue to pursue, which is to promote changes in our country. For this [the U.S.] resorts to old methods, the long-established ones, those of the past, which I have already mentioned. In other words, this policy will continue to support instruments such as subversive programs, illegal radio and television broadcasts, the blockade restrictions that could be eliminated by executive decision and have not been, despite the full extent of executive powers that the president has and in turn, mixed, combined with those instruments of the past are new methods in line with the new bilateral reality, which is the exchanges of all kinds between Cuba and the United States, limited trade in accordance with the minimal restrictions that have been changed so far, dialogue and cooperation with the Cuban government on issues of mutual interest. The call on Congress to lift the blockade is reiterated, arguing that it is a heavy and obsolete burden on the people of Cuba; but, at the same time, it is clearly stated that it is important that the blockade is lifted because it constitutes an impediment to the U.S. in advancing its interests in Cuba. Recognized -- as I said -- is the self-determination and independence of Cuba, the legitimacy of the Cuban government, it is even argued that the United States does not intend to impose a new model in our country and that it corresponds to the Cuban people to make their own decisions; however, at the same time, this directive does not abandon its interventionist designs and the usual behaviour of wanting to interfere in the internal affairs of our country. In summary, the directive in itself contains ideas and intentions that contradict the declared objective to normalize relations with Cuba. On this occasion, we want to reiterate once again that the will of the government of Cuba is to develop respectful and cooperative relations with the United States; but this has to be on the basis of full equality and reciprocity, absolute respect for the independence and sovereignty of Cuba and without interference of any kind. And more in keeping with the theme that we will address today, which is the blockade, coinciding with the presidential policy directive, last Friday, October 14, a new package of measures was also announced by the U.S. Departments of Treasury and Commerce, to modify the application of certain aspects of the blockade. These measures come into effect today. The measures -- as we said last Friday in preliminary statements to the press -- are positive, but have a very limited scope. You only have to view their content to immediately realize this. Most are aimed at expanding transactions that had been previously approved and that, in general, have been very difficult to implement, to put into practice, as a result of the fact that a set of restrictions remain in force that prevent progress in their application. As a summary of these regulations, the fundamental limitations that we observe are: First, investments in Cuba are not permitted, and this is something that President Obama could authorize. Remember that in January 2015, and in his subsequent packages of measures, President Obama approved and authorized investments in Cuba in the field of telecommunications, which demonstrates "Yes, we can," as states the slogan of President Obama himself; however, to date he has not chosen to use the powers he has to allow investments by U.S. companies in Cuba in many other sectors of our economy, not just in telecommunications. There is no expansion of U.S. exports to Cuba beyond the very limited sales that were approved in previous packages, that exclude these products from the United States from being used in essential branches of the Cuban economy. To give you an idea, U.S. exports to Cuba for tourism, or for energy production, or for oil drilling and exploration, or for the mining industry, are not permitted. As you can see, some of the most important industries in our economy. In a general sense, all bans on imports of Cuban products to the United States remain. There is one exception which was approved in this latest package of measures last Friday, finally, after many demands from certain very interested U.S. companies, which is the possibility, from now on, that Cuban pharmaceuticals be exported to the United States, it is the only exception made for products that are produced by Cuban state enterprises. In other words, Cuban state enterprises, in general, are prohibited from exporting to the United States, the only exception now are pharmaceutical products. Welcome news! Of course, we will have to wait for the United States Food and Drug Administration to certify these Cuban products in order that their marketing and distribution in the United States can be defined and materialize; but, again, we believe this is a positive step. I would like to draw your attention to a very curious aspect, when this package of measures was announced last Friday, one thing became world news: U.S. citizens visiting Cuba from now on will be able to buy cigars and rum without limits and take them to the United States for personal use. This has been broadcast across the world. Welcome to U.S. citizens who can now buy cigars and rum in Cuba.... It seems to me that this puts an end to a ridiculous ban, which only permitted U.S. citizens who came to Cuba to buy one music CD, one book, one work of art, as a result of an exception approved in the late 1980s, which allowed the acquisition of informative and cultural materials; however, until now they could not buy rum, or cigars, or coffee, or many other Cuban products that may be of interest and now, finally, this ban has been removed, they may do so; but, careful, take note! This does not mean that Cuban rum and cigar companies are authorized to sell their products in the United States. Therefore, the impact of this measure will be very limited in terms of the benefits the Cuban economy can report. Furthermore, new measures in the financial area were not announced; as you know, Cuba's room for maneuver in the financial sector is still very restricted in terms of relations with the United States and the rest of the world. Although the use of the dollar in Cuba's international transactions was authorized last March, I reiterate that up until today, as I was checking on Saturday [October 15] with Cuban counterparts, up until today, Cuba has still not been able to make cash deposits in this currency or make payments to third parties in U.S. dollars. As such, it is a measure awaiting implementation and this is due, in particular, to the fact that the world's banks remain terrified given the risk which working and interacting with Cuba entails, and the possibility of incurring fines, as has happened considerably in recent years. And the ban on Cuba opening correspondent accounts in U.S. banks has remained unchanged. That is why we believe, and I repeat this today to conclude, that the new measures adopted and which take effect today, benefit the United States more than Cuba and the people of Cuba. The blockade persists. President Obama has just reiterated in the Presidential directive signed last Friday that the blockade should be lifted, but the reality is that he has not exhausted all his executive powers to contribute decisively to the dismantling and removal of the blockade. President Obama will complete his mandate within three months, he leaves, but the blockade remains. While this situation continues, Cuba will continue to present its resolution calling for the lifting of the blockade to the United Nations. We'll do it again in nine days, on October 26, Wednesday; we invite all of you to follow the coverage of this activity which will be broadcast live from the United Nations headquarters in New York, and we hope that, as has happened in recent years, the world, as all of us have already done, will vote against the blockade. Thank you very much. [Applause] Now I invite you, because I told you, I made a promise -- I think I kept it -- that I would speak fairly briefly for such a complex issue, which there is a lot to say about, but we said at the beginning that this was a conversation, so I'd really love for you to ask me any questions, whichever, whatever may serve to clarify information. Rachel, Higher Institute of International Relations (ISRI): You spoke at the beginning on the new regulations or directives that were recently announced. My question is focused on the fact that we are in a context that you yourself noted, of Presidential elections, which are elections that appear more like a circus, we are seeing a scenario between Hillary Clinton and the Republican Party, in this case represented by Donald Trump, we are witnessing that there is actually a position to not pursue Obama's measures. But we see that Hillary does try to maintain this progress that has occurred in relations. Will these new regulations we are witnessing have a short-lived impact? And subsequently, what would be the position, in this case, of the U.S. government following these new regulations? What would be the position in the sense of Republicans and Democrats regarding these regulations? What would be the approach, following these elections, with respect to Cuba-U.S. relations? Will these advances be maintained? Will these advances remain in place or will there be another type of relationship? Thanks. Josefina Vidal: On November 8 everyone, be it early or later that night, depending on how close this election is, will know who will be the next president of the United States, who will take office on January 20, 2017. Once again I reiterate that this Presidential directive is by President Obama. Hence, it is valid in principle and provides instructions for his administration to work on relations with Cuba. The President who succeeds him has no obligation to provide continuity, he or she may revoke it entirely and issue a new directive, he or she can amend it to introduce changes, or may even not touch it, just shelve it and do nothing; that is, it will depend on what the will of the future government is with regard to policy toward Cuba. I believe that, in effect, it is a directive to be fulfilled by the administration of President Obama, but -- and I think this is important, too -- should a future President of that country, now or later, be interested in providing continuity to a process directed toward the normalization of relations with Cuba, I think that this recent document can serve as a point of reference to draw from the experiences that may have been positive and also those things that do not work to advance in that direction. Again, it is a directive from this President that the next is not obliged to maintain, but it can serve as a guide in the future. I recall that in 1985, President Reagan issued a presidential directive instructing the State Department not to grant any member of the Communist Party of Cuba a visa to visit the United States. This directive was apparently still in effect; it is one of those that I am going to confirm to see if it has now been revoked. But, take note -- over the years, was it implemented or not? Reagan implemented it with considerable rigour and practically no Cuban who wanted to go to the United States for cultural, scientific, educational exchanges -- or even government officials -- could visit the country. Then later, other administrations eased its interpretation and did not implement it. This gives you some idea as to how this type of mechanism can play out, but certainly, this is a directive from Obama; there is no obligation that it continue into the future, but, at the same time, it can serve as a reference for a President who would like to follow a similar course. Thank you very much. Jorge Serpa, University of Havana, Geography faculty member: My question is related to the upcoming vote, October 26. We would like to know about the climate in the United Nations at this time, and fundamentally is something known about the position that the state of Israel will take this year. Josefina Vidal: We will know the position taken by countries, especially that of the one you mention, the day of the vote. But I would like to tell you that, as you know, in June, although Cuba made the official presentation here in Havana in September, the Cuban government delivered to the United Nations General Secretary the report on how the blockade of our country continues to be implemented. Many countries of the world, and also UN bodies, presented their own reports explaining how they had been impacted by the extraterritorial, collateral, application of the blockade. Our mission to the United Nations has been very active, constantly keeping all representatives informed of the latest manifestations of the blockade, which until very recently have continued to occur. Last week, I recall, we received information about how an institution refused to transfer the payment of Cuba's dues to the Inter-Parliamentary Union. For two months now, Cuba has not been able to pay its dues and is in default to the Association of Caribbean States, since there are international banks which refuse to handle these transactions, even for the United Nations, and even in other currencies -- not the dollar -- evidence that the blockade is still alive and continues to affect Cuba. Therefore, we again expect, while we cannot predict the vote -- we'll see it on October 26 -- that the international community will stand on Cuba's side and request an end to the blockade. Thank you. Greisy, ISRI: Good day. Professor, on many occasions we have heard that President Obama. or any other President of the United States, has prerogatives to gut the blockade of its content, without waiting for Congress to revoke this law. So, I would like you to remind us once again of these prerogatives that President Obama, or any other President, has -- that he has not used to date. Josefina Vidal: Thank you. As you already know, given the number of years we have been addressing this issue, the blockade began as an executive decision made by President Kennedy, who issued a directive originally establishing what they in their language call a trade embargo of Cuba. That is, first trade with Cuba was cut off, and later other elements were added, in terms of financial relations, services, to become what is today the blockade, which is a tangle of regulations that practically prevent any type of normal relationship between Cuba and the United States in the economic, commercial or financial sphere. In the year 1996, amidst a conflict between sectors that opposed lifting the blockade and others who were pushing for the elimination of this policy, and as a result of tense bilateral relations and the decision of the government to tighten the blockade of Cuba, the Helms-Burton Act was approved and signed by President Clinton in 1996; it was signed in the month of March. Therefore, in the first place, if the blockade is to totally end some day, it is the Congress of the United States that must vote to do so, and, you can just imagine how complicated the voting process is within a Congress where there are 435 Representatives in the House and 100 Senators. But it is a task in which many people are already immersed, and, sooner or later, I think that the blockade's wall will be demolished. Well now, very importantly, at the same time that the Helms-Burton law takes away the President's authority to do that himself -- end the blockade with a stroke of his pen -- in the paragraph immediately below, this law states: This does not eliminate the President's authority to, via licenses, permit certain transactions with Cuba. Thus, the President does maintain, at the same time, other prerogatives - to put it plainly -- to pull some bricks out of the wall, and in fact, Clinton did this. Two years after the Helms-Burton was approved, Clinton for the first time, after some back and forth, eased restrictions a bit on travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens; on the sending of some remittances; some exchanges like those designated as people-to-people, academic exchanges. Clinton did it, and no one objected, because the law acknowledges this as his prerogative. And Obama has been doing this, in a very incipient way at the beginning of his administration, when he again allowed family visits to Cuba, the sending of remittances, and, more often since 2015 to date -- as I have said -- he has issued five packages of measures. And Obama can do more; Obama has not exhausted his powers. I will now summarize for you the things Obama cannot change, because these are written in stone within the different laws that make up the blockade of Cuba. Remember that the blockade is not a single law; there are many. In the first place, as I already said, Obama cannot, on his own, put an end to the blockade; this is up to Congress. Secondly, in 1996, the Helms-Burton Act established that the President cannot permit any transaction involving U.S. properties nationalized by Cuba. For example, as a hypothetical example, but it could be very real, if tomorrow some U.S. company was seeking permission to invest in Cuba, Obama could not [grant it], no other President could, because the Helms-Burton Act prohibits this. Allowing this investment in a factory that prior to the year 1960 may have belonged to a U.S. company and was nationalized, this is prohibited by law. Thirdly, the Toricelli Act, which of course preceded the Helms-Burton, in the year 1992, was one of the first in this latest stage of tightening the blockade. The Toricelli Act prohibits subsidiaries of U.S. companies in third countries from doing business with Cuba. The President cannot change this. For example, if tomorrow an affiliate of General Electric wanted to sell Cuba solar panels, in accordance with Obama's regulations, and needed financing to do so -- something else that is still unresolved -- although it is approved, no bank willing to provide the financing has appeared. But if an affiliate of the General Electric Company in Mexico wants to sell Cuba solar panels, it can't do so; it must be done by General Electric headquarters in the United States, which creates a contradiction. That is, the central headquarters can, but not its affiliates in other countries; this is prohibited by the Torricelli Act. And this is no accident. Because, until 1992, Cuba bought medications from U.S. companies in third countries, and the Toricelli Act stopped these sales, as a way to tighten the blockade of Cuba. In the fourth place, and this was established by a law in the year 2000, the Trade Sanction Reform and Export Enhancement Act -- this is the law that prohibits trips to Cuba for the purpose of tourism, while at the same time allows the limited sales of foods to our country. It prohibits travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens for tourism, while stipulating that U.S. citizens may only come if they qualify within one of the 12 categories listed in the law: academic exchanges, cultural, government officials, relatives of Cubans living there, etc. Thus, although Obama may want to do so, he cannot totally open up travel to Cuba, because this law from 2000 prohibits trips for the purpose of tourism. Fifth, this same law from 2000, which allowed sales of food to Cuba by the United States, for the first time, but subject to many conditions, among them the prohibition on federal or private credit to Cuba -- the obligation to pay in cash, in advance, which puts the agricultural sector of this country at a disadvantage in relation to others, which can, in fact, offer private financing for authorized exports, of course, only when a banking institution willing to grant it appears. These are some of the things Obama, or any other President, cannot do, because they are prohibited by law; but as you see, there remains an enormous area in which he can exercise his powers and, to date, has not done so. Why has he not done so? The United States government insists that the President has reached the legal limit for the use of his prerogatives. Nonetheless, many attorneys in the United States, including those who advise the Cuban government, say no, this isn't the case; there is still a broad spectrum of steps he could take, and has not done so. Nilexys, University of Havana Law School: I participate in the Model United Nations in Havana. First of all, in the name of all who are here, I would like to thank you for taking the opportunity to interact with us in this informal space, clarifying for us certain [questions] on the issue of the blockade. I would like to ask you about the Trading with the Enemy Act, which in September 2015, despite the reestablishment of diplomatic relations, Barack Obama renewed, with the sanctions that are imposed as a consequence. That is, what is the possibility that Barack Obama, if it were possible at this time, or the next President of the United States of America, not renew the sanctions that come with the implementation of the Trading with the Enemy Act, from 1917? Josefina Vidal: Since a law student asks me, with the forgiveness of those not studying law, I have an opening to give an explanation that is complicated. See, I always say that the mother of all the blockade laws is the Trading with the Enemy Act, that goes back to 1917. You can imagine, a law against trade with the enemies of the United States in WWI, but this is the law that has allowed successive U.S. Presidents to impose sanctions on various countries, on the basis of considering the situation one of national emergency. This was the law used in the 1950s to impose sanctions on North Korea; this is the law that was later used to impose sanctions on Cuba and Vietnam, as well. Then came other blockade laws: the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961; the Export Administration Act of 1979; the Toricelli Act of 1992; the Helms-Burton of 1996, and the Sanction Reform Act of 2000, that are the most important. And since then to date, there have been many regulations derived from these laws. Well now, so that you understand a little of the complexity of the issue, in the year 1973, the United States Congress began to question the fact that Presidents of the United States, on the basis of the Trading with the Enemy Act, were imposing sanctions on countries right and left, without even declaring the existence of a national emergency, and affecting the economic interests of the United States. The U.S. Congress decided, at that time, to approve a new law entitled the Emergency Economic Powers Act -- approved in 1973 -- creating the dilemma: What about the sanctions imposed prior to this date? The new law clearly stipulates that, for a President to announce or impose sanctions on more countries, he would be obliged to declare a specific emergency situation, case by case, not basing himself in a general way on an emergency situation in the past, to continue applying sanctions. So you understand, Kennedy decreed the blockade of Cuba without declaring a specific emergency for Cuba, but rather using the same one that had been declared for North Korea during the war on the peninsula in the 1950s. These are strange things that happen, but on the basis of that emergency, they continued imposing sanctions, and then Congress said: No, from now on, to impose sanctions you have to declare an emergency situation case by case. This is what they did in regards to Venezuela. Remember? Last year, before saying that sanctions were being imposed on certain Venezuelan officials, President Obama had to declare an emergency and say that a situation had developed in Venezuela which threatened U.S. interests. Well, in the 1973 discussion, they said: Well, what do we do with the old group of sanctions, on Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam? The decision was to leave them untouched, leave them the way they were. They would continue to exist on the basis of the Trading with the Enemy Act. The 1973 law stipulated therefore that, from that moment on, if the sanctions on Cuba, Vietnam and North Korea were to be continued, every year the President in office would have to say that it was in U.S. interests to maintain these sanctions. This was done with North Korea until George W. Bush eliminated the sanctions as part of a commitment made at that time regarding the nuclear conflict with that country. This was the case with Vietnam until Clinton decided to lift the blockade in 1995, since Clinton could eliminate the sanctions on Vietnam with a stroke of his pen, there was no law to stop him; but the blockade of Cuba was maintained, and therefore, every year, given this 1973 law, the President of the United States is obliged to say that sanctions on Cuba are being maintained under the Trading with the Enemy Act. Very interesting -- and I will end this complicated response at this point -- U.S. government lawyers say that it is convenient to keep the sanctions on Cuba alive under the Trading with the Enemy Act because, they say, this law from back then in 1917 is the source of the executive powers which allow the President to authorize prohibited transactions via licenses, although these are also recognized in the 1996 Helms-Burton Act. Forgive me the complicated explanation, but it is a question that is asked often, and I thought the response would be of interest to you. Of course, it should be mentioned that if some day a President decided to act in a different manner, and not extend the sanctions on Cuba based on the Trading with the Enemy Act, this would not imply that the blockade would disappear, since, remember, there is more legislation in effect sustaining the policy. Lin María, ISRI: So, Obama has been renewing the law all these years? Josefina Vidal: Of course. Not just Obama, since 1973, all the Presidents have had to do it each year; what has occurred in Obama's era is that everyone has paid more attention to this, because clearly, it is a contradiction -- this is obvious -- that he says that the blockade is obsolete, that the blockade hurts Cuba, that the blockade damages U.S. interests, and must be lifted, while at the same time, he signs a paper saying that it is in U.S. interest to maintain the sanctions on Cuba under the Trading with the Enemy Act. These are the big contradictions that we still see in U.S. policy toward Cuba, and which are reflected in the Presidential Directive just approved. Lin María: Professor, the original question, when we talk about this, we always look at it as being about two bands. Right? For the debate, to smooth things between the President and Congress, but within the Congress, what are the positions regarding the blockade, and what economic interests are involved; what interests continue to make the Congress vote in its majority to maintain the blockade? Josefina Vidal: See, there are increasingly visible sectors in Congress -- I must say -- who oppose the blockade, and rejection of the blockade is increasingly bipartisan. As a norm in the past, it tended to be seen that Democrats favoured lifting the blockade, because it was generally so, with Republicans against. Today, this can no longer be said. To a greater degree, we see a core of both Democrats and Republicans who oppose the blockade. Take note, the majority do not oppose the blockade because it hurts Cuba or the Cuban economy -- and this is important to take into consideration -- but in the first place because it hurts the economic interests of the United States, and the strategic interests of the United States in Cuba; but whatever the case, an increase in the debate has been noted, and new forces have joined this rejection of the blockade. There are, at this time, more than 20 proposed bills to modify aspects of the blockade, and strangely enough, the majority of them are being promoted by Republicans, both in the House of Representatives and the Senate. But the situation is very complex in Congress. For a bill to be submitted for debate, it is not enough that a critical mass support the proposal. The leadership of the party which has control of the Senate or House must allow the proposal to be included on the voting agenda. And what has been happening is that, despite the support, despite the bills, especially in the House of Representatives, the leadership opposes the lifting of the blockade, and has not wanted to facilitate a plenary discussion or submit these legislative proposals to a vote. But I should say at the same time, there are a number of legislative proposals meant to reinforce the blockade, to roll back via the legislative route what Obama has done with his executive powers. Thus, this situation, I believe, is going to be maintained for the time being. There are Congressional elections now, and I believe we'll have to wait until next year to see how this debate moves forward. I think the rain is putting an end to the time we had planned for this exchange. Is there another question? Unidentified student: Professor, I would like to ask you... since the report on damage caused by the blockade has been submitted to the UN, we would like to hear about some of the damages caused this last year, the increased or decreased numbers of losses in our economy, in the health care sector, etc. Josefina Vidal: In Cuba's report on the blockade there are many, many figures. I can't give them to you exactly from memory. The damages in a single year have been more than $4 billion [$4.68 billion] and those accumulated since the blockade was imposed surpass $125 billion [$125.873 billion]; based on the depreciation of the dollar in relation to the price of gold on the international market, damages reach more than $700 billion [$753.688 billon]. There are many examples of damages in the health sector, in the area of food, to transportation and biotechnology. Best to look over the report and you'll see many facts there that should be of interest, and show that the blockade hurts the entire economy and all sectors of our society. I think we need to end, thank you all very much. [Applause] See you soon.

(Granma) Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca |

There have been discussions

on this, since last Friday, at

the Foreign Ministry, through the Cuban press, on digital sites

like Cubadebate, but I think it is important, as we had a

little more time over the weekend to think about this, as these

measures were announced just last Friday, October 14, to share

with you some thoughts and some preliminary conclusions, which we

have reached following the study and analysis of these two

announcements.

There have been discussions

on this, since last Friday, at

the Foreign Ministry, through the Cuban press, on digital sites

like Cubadebate, but I think it is important, as we had a

little more time over the weekend to think about this, as these

measures were announced just last Friday, October 14, to share

with you some thoughts and some preliminary conclusions, which we

have reached following the study and analysis of these two

announcements.

It's interesting that upon

presenting this directive,

announced was the revocation of many others that had been in

place in the past. Now we are doing a study and asking for the

support of colleagues who are well informed on the topic. We are

doing a historical investigation to identify these other

directives which were operational, and no previous President had

revoked, but were simply not being implemented, which also gives

us some idea of what could happen in the future.

It's interesting that upon

presenting this directive,

announced was the revocation of many others that had been in

place in the past. Now we are doing a study and asking for the

support of colleagues who are well informed on the topic. We are

doing a historical investigation to identify these other

directives which were operational, and no previous President had

revoked, but were simply not being implemented, which also gives

us some idea of what could happen in the future.