|

March 5, 2010 - No. 48 -

Supplement Centenary of Resolution to Establish

International Women's Day History of International Women's Day

|

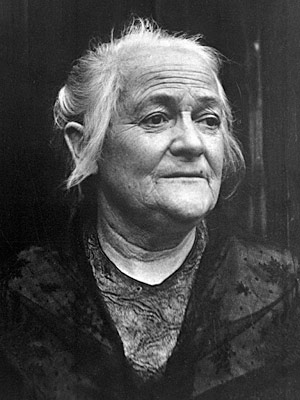

German communist Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), who put forward the original proposal for International Women's day in 1910. She was a member of various revolutionary organizations from her youth and was exiled on several occasions for her political activities. |

Stating that the socialist parties in all countries are "bound to fight with energy for the introduction of Woman's Suffrage" it says that the socialist women's movement must take part in the struggles organized by the socialist parties for the democratization of the suffrage, while at the same time ensuring that within this fight the "question of the Universal Woman Suffrage is insisted upon with due regard to its importance of principle and practice."

The resolution to establish International Women's Day states,

"In order to forward political enfranchisement of women it is the duty of the Socialist women of all countries to agitate according to the above-named principles indefatigably among the labouring masses; enlighten them by discourses and literature about the social necessity and importance of the political emancipation of the female sex and use therefore every opportunity of doing so. For that propaganda they have to make the most especially of elections to all sorts of political and public bodies."

The delegates resolved,

"In agreement with the class-conscious political and trade organizations of the proletariat in their country the socialist women of all nationalities have to organize a special Woman's Day, which in first line has to promote Women Suffrage propaganda. This demand must be discussed in connection with the whole women's question according to the socialist conception of social things."

A "Woman's Day" had been organized the previous year in the United States, on the last Sunday in February 1909, by the National Women's Committee of the American Socialist Party marked by demonstrations for women's rights. Women's suffrage along with the rights of women workers, particularly in the garment trade, were the focus of these demonstrations. This Woman's Day honoured the thousands of women involved in the numerous labour strikes in the first years of the twentieth century in many cities, including Montreal, Chicago, Philadelphia and New York. This was a period when women entered the labour force in their thousands and alongside working men fought to organize collectively and to improve their brutal conditions of work.

Later in 1909, needle-trade workers in New York City -- 80 percent of whom were women -- walked off their jobs and marched and rallied for union rights, decent wages and working conditions in the "Uprising of 20,000." The work stoppage was reportedly referred to as the "women's movement strike" and continued from November 22, 1909 to February 15, 1910. The Women's Trade Union League provided bail money for arrested strikers and large sums for strike funds during the work stoppage.

Early Celebrations of International Women's Day

March 19, 1911 was the date set for the first International Women's Day by the Second International Conference of Socialist Women and, implementing their resolution, rallies held in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland on that day were attended by more than one million women and men. "The vote for women will unite our strength in the struggle for socialism" was the call of these rallies. In addition to their demand for the right to elect and be elected, they demanded the right to work, to vocational training and to an end to discrimination on the job. A woman socialist wrote at that time:

"The first International Women's Day took place in 1911. Its success exceeded all expectation. Germany and Austria on Working Women's Day was one seething, trembling sea of women. Meetings were organized everywhere -- in the small towns and even in the villages halls were packed so full that they had to ask male workers to give up their places for the women.

"This was certainly the first show of militancy by the working woman. Men stayed at home with their children for a change, and their wives, the captive housewives, went to meetings. During the largest street demonstrations, in which 30,000 were taking part, the police decided to remove the demonstrators' banners: the women workers made a stand. In the scuffle that followed, bloodshed was averted only with the help of the socialist deputies in Parliament."

The following year, women in France, the Netherlands and Sweden joined in actions marking International Women's Day. In the period leading up to the declaration of World War I, the celebration of International Women's Day opposed imperialist war and expressed solidarity between working women of different lands in opposition to the national chauvinist hysteria of the ruling circles. For example, in Europe International Women's Day was an occasion when speakers from one country would be sent to another to deliver greetings.

Russian women observed their first International Women's Day on the last Sunday in February 1913 (on the Julian calendar, which corresponded to March 8 on the Gregorian calendar in use elsewhere), under conditions of brutal Tsarist reaction. There was no possibility of women organizing open demonstrations but, led by communist women, they found ways to celebrate the day. Articles on International Women's Day were published in the two legal workers' newspapers of the time, including greetings from Clara Zetkin and others.

An essay written in 1920 by a woman communist activist at that time described the 1913 celebration:

"In those bleak years meetings were forbidden. But in Petrograd, at the Kalashaikovsky Exchange, those women workers who belonged to the Party organized a public forum on 'The Woman Question.' Entrance was five kopecks. This was an illegal meeting but the hall was absolutely packed. Members of the Party spoke. But this animated 'closed' meeting had hardly finished when the police, alarmed at such proceedings, intervened and arrested many of the speakers.

"It was of great significance for the workers of the world that the women of Russia, who lived under Tsarist repression, should join in and somehow manage to acknowledge with actions International Women's Day. This was a welcome sign that Russia was waking up and the Tsarist prisons and gallows were powerless to kill the workers' spirit of struggle and protest."

Women in Russia continued to celebrate International Women's Day in various ways over the ensuing years. Many involved in organizing landed themselves in Tsarist prisons as the slogan "for the working women's vote" had become an open call for the overthrow of the Tsarist autocracy.

The first issue of "The Woman Worker" (Rabotnitsa), a journal for working class women, was published in 1914. That same year, the Bolshevik Central Committee decided to create a special committee to organize meetings for International Women's Day. These meetings were held in the factories and public places to discuss issues related to women's oppression and to elect representatives from those who had participated in these discussions and the resulting proposals to work on the new committee.

International Women's Day 1917 in Russia

In Russia, International Women's

Day 1917 was a time of

intense struggle against the Tsarist regime. Workers, including women

workers in textile and metal working industries, were on strike in the

capital city and opposition to Russia's participation

in the imperialist war raging in Europe was growing. On March 8

(February 23 on the Julian calendar), women in their thousands poured

onto the streets of St. Petersburg in a strike for bread and peace. The

women factory workers, joined by wives of soldiers and other women,

demanded, "Bread for our children"

and "The return of our husbands from the trenches." This day marked the

beginning of the February Revolution, which led to the abdication of

the Tsar and the establishment of a provisional government.

In Russia, International Women's

Day 1917 was a time of

intense struggle against the Tsarist regime. Workers, including women

workers in textile and metal working industries, were on strike in the

capital city and opposition to Russia's participation

in the imperialist war raging in Europe was growing. On March 8

(February 23 on the Julian calendar), women in their thousands poured

onto the streets of St. Petersburg in a strike for bread and peace. The

women factory workers, joined by wives of soldiers and other women,

demanded, "Bread for our children"

and "The return of our husbands from the trenches." This day marked the

beginning of the February Revolution, which led to the abdication of

the Tsar and the establishment of a provisional government.

The provisional government made the franchise universal, and recognized equal rights for women. Following the October 1917 Revolution, the Bolshevik government implemented more advanced legislation, guaranteeing in the workplaces the right of women to directly participate in social and political activity, eliminating all formal and concrete obstacles which previously had meant the subordination of their social and political activity and their subservience to men. New legislation on maternity and health insurance was proposed and approved in December 1917. A public insurance fund was created, with no deductions from workers wages, that benefited both women workers and male workers' wives. It meant that women were now treated second to none as neither they nor their children were dependent on spouses and fathers for their well-being.

After 1917

March 8 as International Women's Day became official in 1921 when Bulgarian women attending the International Women's Secretariat of the Communist International proposed a motion that it be uniformly celebrated around the world on this day. March 8 was chosen to honour the role played by the Russian women in the revolution in their country, and through their actions, in the struggle of women for their emancipation internationally.

The first IWD rally in Australia was held in 1928. It was organized by the communist women there and demanded an eight hour day, equal pay for equal work, paid annual leave and a living wage for the unemployed.

Spanish women demonstrated against the fascist forces of Gen. Francisco Franco to mark International Women's Day in 1937. Italian women marked IWD 1943 with militant protests against fascist dictator Benito Mussolini for sending their sons to die in World War II.

In this way, since 1917, International Women's Day has been both a day of celebration of women's fight for their rights and the rights of all and a day to militantly affirm the opposition of women to imperialist war and aggression. Its spirit has always been that to win the rights of women and the fight for security and peace, women must put themselves in the front ranks of the fight and of governments which represent these demands.

Canada Ranks 47th

Women's Participation in Electoral Politics

Left to right: Nellie McClung, Emily Murphy and Laura Jamieson, prominent suffragists and leaders of the women's movement in western Canada, pictured in March 1916. |

The political system in Canada, founded on the enfranchisement of white men of property, has from the beginning been a block to women's participation in politics -- both to their basic right to participate in their own governance and to set the direction of the society. Women could not vote federally until 1921 and they were not legally considered persons until 1928. This extension of the suffrage did not include any persons of aboriginal origin who remained excluded until 1960.

History of Women's Participation in Electing and Being Elected

The history of women's struggle for the recognition of their right to elect and be elected in Canada was concurrent with struggles in the labour movement which as soon as it began organizing in the 1870s demanded an end to the property restrictions on the right to vote. Some twenty years later the labour movement took up the demand for universal suffrage for men and women.

From the 1870s, women organized actions to press for

recognition of their rights, including a sit-in in the Alberta

legislature. In 1876 the Toronto Women's Literary Club was founded for

the purpose of organizing for women's suffrage. The same year women in

British Columbia presented the first

suffrage petition to the provincial Legislature. Many petitions

followed to legislatures across Canada. In 1889, the Dominion Women's

Enfranchisement Association was formed to incorporate all suffrage

groups in the country.

In the period from 1885 to

1898 the question of drawing

up voters lists and determining who was eligible to vote rested with

the federal government. In 1898 new federal legislation returned this

responsibility to the provinces, where it had rested from confederation

to 1885. This meant that whether

women could vote in both federal and provincial elections was

determined by the legislation in their province of residence and thus

the suffrage movement turned its attention to winning suffrage

provincially.

In the period from 1885 to

1898 the question of drawing

up voters lists and determining who was eligible to vote rested with

the federal government. In 1898 new federal legislation returned this

responsibility to the provinces, where it had rested from confederation

to 1885. This meant that whether

women could vote in both federal and provincial elections was

determined by the legislation in their province of residence and thus

the suffrage movement turned its attention to winning suffrage

provincially.

Women won the right to vote and to stand as candidates in 1916 in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, and in 1917 in BC. In Ontario women won the vote in 1917, but were still not permitted to run as candidates. On the eve of the 1917 general election, women in all provinces from BC to Ontario had the vote by virtue of provincial electoral law; women living east of the Ontario/Quebec border did not. The Conservative government of the day was in crisis over whether it would be booted out of office because of widespread opposition to conscription. It passed two pieces of self-serving electoral legislation. The Elections Canada document "A History of the Vote in Canada" states:

"Bluebirds" voting at a Canadian field hospital in France in December 1917. |

"The Military Voters Act, was designed to increase the number of electors potentially favourable to the government in power. As its title suggests, the law defined a military voter as any British subject, male or female, who was an active or retired member of the Canadian Armed Forces, including Indian persons and persons under 21 years of age, independent of any residency requirement, as well as any British subject ordinarily resident in Canada who was on active duty in Europe in the Canadian, British or any other allied army. (Thus, some 2,000 military nurses -- the "Bluebirds" -- became the first Canadian women to get the vote)...."

"The second law, the War-Time Elections Act, had a dual purpose: to increase the number of electors favourable to the government in power and decrease the number of electors unfavourable to it. The law conferred the right to vote on the spouses, widows, mothers, sisters and daughters of any persons, male or female, living or dead, who were serving or had served in the Canadian forces, provided they met the age, nationality and residency requirements for electors in their respective provinces or Yukon...."

"Finally, the legislation of September 20, 1917, stripped the provinces of the responsibility for drawing up electoral lists and gave the task to enumerators appointed by the federal government -- in other words, by the Conservatives as the party in power."

Agnes MacPhail |

The War-Time Elections Act swelled the electoral lists by some 500,000 names, but it also effectively denied the vote to women who would otherwise have had it by virtue of provincial law but who did not have a relative in the armed forces.

The 1917 election was the last general election in which women were denied the vote. A federal "Act to Confer the Electoral Franchise upon Women" received royal assent on May 24, 1918. A 1919 law also set out that women could be nominated as candidates in federal elections: "Legislation in 1920 provided universal access to the vote without reference to property ownership or other exclusionary requirements -- age and citizenship remained the only criteria. Provincial control of the federal franchise was now a thing of the past. The general election of 1921 was the first open to all Canadians, men and women, over the age of 21" (Elections Canada, "A History of the Vote in Canada"). In 1921 four women ran in the general election and Agnes MacPhail was elected.

The following figures from the Canadian parliamentary website show how many woman candidates have run in each general election:

| Election |

Women Candiates |

Number Elected |

| 1921 | 4 |

1 |

| 1925 |

4 |

1 |

| 1926 |

2 |

1 |

| 1930 |

10 |

1 |

| 1935 |

16 |

2 |

| 1940 |

9 |

1 |

| 1945 |

19 |

1 |

| 1949 |

11 |

0 |

| 1953 |

47 |

4 |

| 1957 |

29 |

2 |

| 1958 |

21 |

2 |

| 1962 |

26 |

5 |

| 1963 |

40 |

4 |

| 1965 |

37 |

4 |

| 1968 |

36 |

1 |

| 1972 |

71 |

5 |

| 1974 |

137 |

9 |

| 1979 |

195 |

10 |

| 1980 |

218 |

14 |

| 1984 |

214 |

27 |

| 1988 |

302 |

39 |

| 1993 | 476 |

53 |

| 1997 |

408 |

62 |

| 2000 |

373 |

62 |

| 2004 |

391 |

65 |

| 2006 |

380 |

64 |

| 2008 |

445 |

69 |

More women stood as candidates in the 1993 general

election than any other (see bolded figures in table above) and 41.8

percent of the women who ran as candidates did so either as

independents or for parties which had no seats in the House of Commons.

This election took place one year after the

Canadian people defeated the Charlottetown Accord, in which the

National Action Committee on the Status of Women opposed the Accord.

This was the election that ended the old equilibrium in the House of

Commons of a national party in power and in opposition.

For the entire period from 1993 to the present, 30 percent, and in most cases more than one-third, of women candidates who ran federally did so as independents, or candidates of parties which do not have any seats in the House of Commons.

Women in the Senate

The first woman appointed to the Canadian Senate, Emily Murphy, was prevented from taking her seat on the grounds that women were not "persons." She contested the legal interpretation of the word "person" before the Supreme Court of Canada in 1927. In its ruling, the Canadian Court stipulated that the term "person" did not apply to women, alleging that when the British North America Act was signed, jurisprudence did not consider women as "qualified persons." Five women from Alberta: Judge Emily Murphy, Mrs. Nellie McClung, Mrs. Louise C. McKinney, Henrietta Muir Edwards and Irene Parlby appealed this ruling before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of London which ruled that women were persons in the eyes of the law. In 1930 Mrs. Cairine Reay MacKay Wilson was appointed the first woman senator.

Women in Cabinet

The first woman to be a member of the federal cabinet was Ellen Loucks Fairclough, who served from 1957-64 in the Diefenbaker government. She was followed by Judy LaMarsh in the Pearson government from 1963-68. For the entire period from 1968-84 there were no more than three women in cabinet at any one time and they generally held low profile portfolios.

Since that time the number of women appointed to cabinet has increased. The current Harper government has 11 women in Cabinet out of 38, or 29 percent of the cabinet. Despite Harper's claim to have the most women cabinet ministers the number of women in cabinet is the same as in the Martin government.

Women's Participation in Electoral Politics in Canada vs. Other Countries

As of November 2009, figures published by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) show that Canada placed 47th of the 187 countries included in the results for the participation of women in the national parliament.

By way of comparison:

| Country |

Ranking |

Percentage of Women |

Number of Women |

| Rwanda | 1 | 56.3 |

45 |

| Sweden |

2 |

47 |

164 |

| South

Africa |

3 |

44.5 |

178 |

| Cuba |

4 |

43.2 |

265 |

| Iceland |

5 |

42.9 |

27 |

| Afghanistan |

30 |

27.7 |

67 |

| Iraq |

39 |

25.5 |

70 |

| Canada |

47 |

22.1 |

68 |

| United

States |

71 |

16.8 |

73 |

According to a 2007 report by the IPU, as of that time 17.7% of all parliamentary seats worldwide were held by women, as compared to 11.8% in 1995. In the Americas this increase was from 12 percent in 1995 to 20 percent in 2007.

In elections in 2007 women took 2,013 or 16.9 percent of the parliamentary seats which were up for 'renewal' in 63 countries. Of the seats taken by women 1,764 were directly elected, 116 were indirectly elected and 133 were appointed (for example, to an unelected senate). The IPU states that "Electoral systems matter: women gained more seats in parliamentary chambers elected using proportional electoral system 18.3 percent, compared to 13.8 percent for those elected with a majority or plurality electoral system."

(Data: Elections Canada)

Read The Marxist-Leninist

Daily

Website: www.cpcml.ca

Email: editor@cpcml.ca