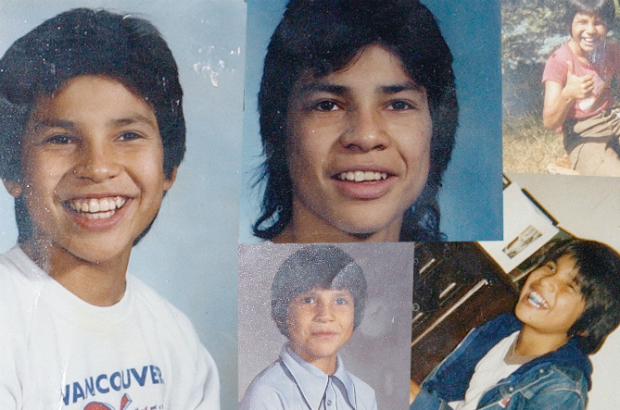

Story of Neil Stonechild

Almost 14 years after the body of Neil Stonechild was found in a frozen field in Saskatoon's north end, a judicial inquiry released the result of its examination of the original police investigation into Stonechild's death. On October 23, 2004, the Saskatoon StarPhoenix outlined the case, the allegation, the key police players and the revelations. The CaseWhen Neil Stonechild's frozen body was found in a snowy field in the city's north end during the noon hour of Nov. 29, 1990, the first question that occurred to most people associated with the case was, "How did he get there?" The 17-year-old was last seen alive five days earlier in the west-side neighbourhood of Confederation Park. Did he walk the nine kilometres to the huge undeveloped area between 47th and 48th streets during a cold, windy snowfall? Did he get a ride into the area? Why was one of his shoes missing? Did the blackened, worn-through sock on his shoeless foot indicate that he had walked a long distance without the shoe? Despite the questions, former Saskatoon police Sgt. Keith Jarvis closed the file after a three-day investigation with a simple, unsubstantiated explanation. "It is felt that unless something concrete by way of evidence to the contrary is obtained, the deceased died from exposure and froze to death. There is nothing to indicate why he was in the area other than possibilities he was going to turn himself in to the correctional centre or was attempting to follow the tracks back to Sutherland group home, or simply wandered around drunk until he passed out from the cold and alcohol and froze. Concluded at this time," Jarvis wrote in his report of Dec. 5, 1990. Four months after the death, Stonechild's mother, Stella Bignell, criticized the police investigation in an article in The StarPhoenix. She didn't think enough had been done to rule out the possibility of foul play. She thought the investigation would have been more thorough if Neil had been the mayor's son. The police spokesperson at the time was Sgt. Dave Scott, who later became chief of police. In response to the criticism, Scott declared police had done a thorough investigation and had "pursued every avenue." "A tremendous amount of work went into that case," Scott said in 1991. The Stonechild file was destroyed in a routine purge about seven years later, but a copy of it had been preserved at the home of a constable, Ernie Louttit, who was dissatisfied with the investigation. Questions about the case resurfaced in 2000, when a

massive

RCMP task force was created to look into allegations of police

abandoning aboriginal men on the outskirts of Saskatoon.   Darrell Night, in 2002, revisits the location where he was dumped by Saskatoon police in January 2000, in -20C weather. (K. Hogarth/NFB) The issue arose after Darrell Night, a Cree man, came

forward

in February 2000 saying two officers had left him near the Queen

Elizabeth Power Station on a freezing night, while he was drunk

and inadequately dressed for the weather. The allegation was explosive because the frozen bodies of two other aboriginal men, Lawrence Wegner and Rodney Naistus, had recently been found in the same vicinity with no explanation for how they ended up there. Also within weeks, reporters resurrected a three-year-old humour column that had been written by Saskatoon Const. Brian Trainor for the Saskatoon Sun. The column tells of two rookie officers who drive a troublesome, drunken man, whose race is not identified, to the Queen Elizabeth plant, where they order him to get out. In the midst of allegations against the police, Stonechild's family and friends reminded the media about Neil's death. Central to their complaints were the allegations of Stonechild's friend, Jason Roy, who had been with Stonechild the night he was last seen alive. Within weeks of Stonechild's death, Roy had told friends that he had seen Stonechild in the back of a police cruiser, handcuffed and bleeding and yelling, "They're gonna kill me." The RCMP conducted an exhaustive investigation but were not able to verify or dismiss Roy's allegation. No charges were laid in the Stonechild case but in February 2003, then-justice minister Chris Axworthy appointed Justice David Wright as commissioner of an inquiry to look into Stonechild's death and the original police investigation. The AllegationThe Stonechild inquiry probably would not have been called if not for Roy's explosive allegation. Roy was a rebellious 16-year-old with a drinking problem in November 1990. Many elements of his story have been substantiated by other people and by police computer records. But some of the evidence also casts doubt on the veracity of his claims. Early in the evening of Nov. 24, 1990, at Stonechild's house, Stonechild and Roy struck a deal with Stonechild's brother to buy them a bottle of vodka. Neil unknowingly had his last conversation with Bignell. Stonechild was at large from an open custody youth group home at the time and promised his mother he would turn himself in at the end of the weekend, a point that figured in the conclusion Jarvis wrote to his investigation. Roy says he and Stonechild drank the entire bottle of vodka themselves by about 11:30 p.m. at their friend Julie Binning's house in Confederation Park, on Milton Street. Though it was blowing snow and well below -20 C, Stonechild convinced Roy to join him in going to see his friend Lucille Neetz, who was babysitting a few blocks away. The pair trudged to the Snowberry Downs apartment complex at 33rd Street and Wedge Road, where they caused a disturbance that led to police being called. They buzzed various suites in more than one building, before Roy says he wanted to give up and go back to the Binning's. The boys argued, and Roy left Stonechild and headed back. He thinks he stopped to warm up at a 7-Eleven. As he walked south on Confederation Drive, he says a police car emerged from an alley in front of him and stopped. Roy says Stonechild was in the back seat, his hands were cuffed behind his back, there was blood on his face and he was calling Roy by name. The driver asked him if he knew the youth in the back, Roy says, adding he denied knowing Stonechild because he feared he would be arrested too. Instead, when asked his name, Roy gave the name and birth date of his cousin, Tracy Horse, whom he knew had no criminal record. The police checked the name and allowed him to go. As the police drove away, Stonechild seemed afraid as he yelled, "They're gonna kill me," Roy said. Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) records have shown that constables Larry Hartwig and Brad Senger used their on-board computer that night to check Tracy Horse, as Roy claims. Horse told the inquiry he was not stopped by the police that night. The CPIC records also show that eight minutes later the same police officers checked the name of Bruce Genaille. Genaille, coincidentally, was Stonechild's cousin, who also was walking on Confederation Drive late that night. He said he is certain there was nobody in the back of the police car when he was checked. If Stonechild had been in the car when the police stopped Roy, where was he when they checked Genaille? And why were police still looking for Stonechild if they had just had him in their custody? Would eight minutes have been long enough for the police to drive in a winter storm all the way to the north industrial area and back? Roy also made the disturbing allegation that he told the police about seeing Stonechild in custody, but that he was intimidated into giving a second, false statement that cleared the police. "I lied for my life," Roy told the inquiry. The dates in Roy's story didn't mesh with other information heard at the inquiry. Roy said he gave the false statement clearing police on Dec. 20, 1990, but Louttit, the officer who preserved the only existing copy of that statement, said he photocopied it from the file on Dec. 5 or 6. Key Officers- Const. Lawrence Hartwig had been with the Saskatoon police for almost four years in November 1990 when he was dispatched to the disturbance involving Stonechild. He had previously been partnered with Const. Ken Munson from January to October 1990. Munson and Dan Hatchen were convicted of abandoning Night in January 2000. Hartwig knew Stonechild from previous incidents, including a break and enter of which Stonechild was convicted, and had once given him a ticket for driving without a licence. - Const. Brad Senger was a rookie with the department. He and Hartwig had never been partnered before that night. Both said Stonechild was gone from the scene of the disturbance when they arrived that night. Both said they never saw the youth that night. - Const. Ernie Louttit photocopied the Stonechild investigation file on Dec. 5 or 6, 1990, soon after Jarvis concluded it. He kept the file at home, thereby preserving evidence that has proven key to understanding events of the time and shedding light on the police investigation, after the original file was destroyed. Louttit became unofficially involved after Stonechild's brother, Jason, known as Jake, told him he'd heard rumours that Neil had been beaten by Gary Pratt and dumped in the north end. Pratt was a friend of the Stonechild brothers with whom Neil had supposedly had a violent falling out. Louttit, an aboriginal former soldier who'd been with the Saskatoon police for three years, also visited Bignell, Stonechild's mother. In January 1991, he complained to Jarvis about the incomplete investigation. Louttit felt Jarvis discounted his concerns and indicated he should back off or risk being disciplined for meddling. Months later, Louttit checked the file and found no reference to the tip he had been provided from Jake or to his meeting with Jarvis. Louttit didn't remember he still had the investigation file when the case was reopened by the RCMP in 2000. It was March 2001 before he came across it while looking for something else. None of the police who responded to the scene of Stonechild's frozen body said they considered it their responsibility to find out how the youth had arrived in the field in the north industrial area. Most police who testified didn't remember the occurrence and the written notes of some had disappeared without clear explanation. - Const. Rene Lagimodiere, the first officer on the scene, quickly assessed the situation and discounted the possibility of foul play. He did ask that a dog handler be sent out to search for the victim's missing shoe. The other officers who attended the scene took a similar view and said they considered their roles as collecting information for the investigator, whom they assumed would use their information in the real investigation. - Sgt. Robert Morton took photographs and a video of the scene and took a thumbprint at the morgue. In 1993, at Jarvis' direction, he destroyed Stonechild's blue bomber jacket, jeans, underwear, both socks and the one shoe he was found with. - Sgt. Michael Petty was the highest-ranking officer on the scene. He decided the matter was not suspicious and did not warrant a major crimes investigator attending the scene. He treated the matter as a sudden death and referred it to the morality unit. Petty said it was his responsibility to make sure the police could rule out foul play, yet he acknowledged he didn't know the victim was missing a shoe, that there were injuries on the face or whether someone had deliberately left the victim in the remote location. - Sgt. Keith Jarvis, who had been with the force for 24 years at that time, was assigned the case several hours later when he arrived at work. He assumed that since the death had been assigned to the morality unit, that it had already been cast as a sudden death, not a suspicious one. He went to the morgue with Morton, but says he didn't look at the body and never saw two parallel abrasions on the nose. People who attended Stonechild's funeral said the scratches looked like cuts and thought he had been beaten before he died. Jarvis said he never went to the scene where the body was found, never looked at the video or the photographs taken at the scene or at the autopsy, never looked at Stonechild's clothing and didn't phone people whose photographs were found in his pockets. He interviewed a few witnesses and the next day wrote in a report that the file should be sent to major crimes. Then he went on a four-day leave. When he returned, he found that the file was still on his desk and that no further work had been done on it. He didn't ask his superior why the file had remained idle in his absence but worked on it for several hours that day, before concluding it. Jarvis called the pathologist who had performed the autopsy and found that Stonechild had not been beaten to death. Jarvis was aware of rumours that Pratt had beaten and dumped Stonechild, but he never contacted Pratt to question him. He stated in his report that the rumours were probably just somebody's attempt to cause trouble on the street for the Pratts. He didn't include any information about talking to the two constables who were dispatched to the disturbance involving Stonechild. Jarvis closed the file without waiting for the toxicology report, which would have told him how much alcohol Stonechild had in him when he died, a point which was central to Jarvis' theory about the circumstances of the death. Stonechild was found to have about twice the legal driving limit of alcohol in his blood, which expert witnesses said was not enough to cause the youth to pass out. In what appeared to be a shocking revelation, Jarvis told RCMP investigators in 2000 and 2001 that Roy told him he had seen Stonechild in the police cruiser. On the eve of the inquiry, Jarvis recanted, saying he didn't think he had a real memory of Roy telling him about Stonechild in the car. Jarvis said he thought suggestions by the RCMP had implanted a false memory when they were trying to jog his vague recollection of his interview with Roy. The taped interview confirmed he had wondered about the source of the memory at the time of the apparent admission. - Staff Sgt. Bud Johnson, Jarvis's direct supervisor, never questioned the work, which his fellow officers declared "incomplete," "inadequate" and "poor policing." He doesn't remember anything about the case, and said he doesn't know why he didn't refer it to major crimes as Jarvis requested, why he didn't keep someone working on it while Jarvis was away or why he authorized closure of the unfinished file. - Sgt. Dave Scott, who was the police spokesperson and who later became chief of police, defended the investigation when Bignell's complaint came to him through a media interview. He declared the work sound and the matter unfortunate. At the inquiry, he denied deliberately suppressing information about the case. Scott didn't think Bignell's allegation of police racism was important enough to discuss with then-chief Joe Penkala, even after the criticism appeared on the front page of the paper. - Chief Joe Penkala declared that he was never told of Stonechild's death or the investigation. He said he never saw the front-page newspaper article and suggested that members of the force deliberately withheld the information from him. Penkala changed a point in his testimony after documentation proved his first statement false. On his first day on the stand, Penkala said he wasn't aware of the Stonechild case because he had been on holiday in December and early 1991. When his appointment diary was produced, the inquiry found that he had been at work the last days of November to Dec. 10 and had been on duty in March when the newspaper story ran. - Deputy chief of operations Murray Montague and deputy chief of administration Ken Wagner were in charge when Penkala was away. - Insp. Frank Simpson was supposed to oversee Johnson's work. Johnson, Simpson, Montague, Penkala and Scott were among executives who met every day to discuss important ongoing matters. All agreed the death amid rumours of a violent feud should have attracted their attention and further investigation. Not one had an independent memory of the death or the front-page article. - Coroner Dr. Brian Fern attended the scene, checked the body for obvious trauma and formed the opinion the youth had not died as a result of any injuries but from the cold. Fern could have ordered a coroner's inquest to uncover the circumstances around the death, but didn't. - Deputy chief Dan Wiks, the highest-ranking, current member of the force to testify, was in charge of the police service response to the RCMP investigation and the inquiry from 2000 to 2004. He answered questions about a special committee called to address related matters. Notes from the committee meetings revealed that in 2003 Wiks had given a StarPhoenix reporter incorrect information about why the two constables suspected by RCMP in the case had not been suspended while the matter was investigated. Wiks was subsequently charged under provincial police regulations with discreditable conduct. The matter is currently awaiting a provincial disciplinary hearing. - Inspector Jim Maddin, who later became Saskatoon mayor, said there was concern in the police service about the Stonechild file and there was knowledge two officers may have had some involvement with the youth "about the time of his demise." He does not believe high-ranking officers who say they didn't know about the Stonechild case. - Sgt. Eli Tarasoff knew the Stonechild boys and their mother. He told Jarvis he thought the file had been closed prematurely but said Jarvis was "flippant" about it. The Revelations- When constables Hatchen and Munson were convicted of forcible confinement for driving Night to the Queen Elizabeth plant, police declared that the incident was an isolated incident. Hatchen and Munson were sentenced to eight-month jail terms and were fired from the force. Testimony at the inquiry, however, confirmed that Saskatoon police have taken people to unauthorized locations over the years. Several officers said they know of such incidents. Const. Brett Maki said police sometimes use their discretion in deciding to release people and do not always make notes about having done so. Former staff sergeant Bruce Bolton said that he "took a person out 11th Street," about 35 years ago. Other police witnesses referred to an officer who was disciplined years ago for dropping someone off in an unauthorized location. Commission counsel Joel Hesje said if police knew that fellow officers sometimes dropped people off in unauthorized locations, it could have affected the way the Stonechild death was investigated. - Allegations of police involvement in the death appeared to be supported by physical evidence when the inquiry viewed a startling photograph of handcuffs superimposed over Stonechild's face. The image showed two metal strips of the cuffs aligning with two parallel abrasions that ran diagonally across the teenager's nose, suggesting he may have received a blow to the nose with a handcuff. Gary Robertson, an image measurement specialist, or photogrammetrist, put forward that theory as his expert opinion. But Robertson's credibility was called into question by police lawyers who revealed he had inflated his educational credentials. Robertson's opinion about the possibility Stonechild's nose had been broken and his observations about the marks on the teenager's skin were called into question by lawyers who pointed to his lack of training in medicine or human physiology. The lawyers pointed out that medical pathologists were less certain on the same points. Three pathologists said they couldn't rule out

handcuffs as

the cause of the abrasions but all said they could have been made

by Stonechild falling onto frozen stalks of weeds that were

visible in photographs from the scene.

Website: www.cpcml.ca Email: editor@cpcml.ca |